The Trek Supercaliber has never pretended to be something it’s not. Laser-focused on XC racing, the goal has always been ultra-efficient pedaling with just enough suspension to serve as a viable hardtail replacement, and by and large, it’s been highly successful in that endeavor. Trek has now updated the Supercaliber for 2024, giving it more suspension travel for more capability on rougher tracks, dropping the weight by a couple hundred grams, and updating the geometry for more confident descending and climbing manners, while also making it more versatile overall without dulling its sharpness.

Others may have followed in its footsteps, but the latest updates seem to firmly cement the Supercaliber as the front-runner in the category.

The short of it: Trek’s premier XC racing platform, updated with more suspension travel and a more versatile geometry.

Good stuff: Superb pedaling efficiency, surprisingly effective suspension, great handling, blisteringly fast, dropper post included.

Bad stuff: Still isn’t super light, overly stiff cockpit, questionable rear shock reliability.

More, but yet less

Perhaps the most significant change is the increase in suspension travel at both ends.

The original Supercaliber debuted in 2019 with just 60 mm of movement out back, paired with a 100 mm-travel fork. The idea here was to retain the front-end sharpness of the ultra-lightweight hardtails that were still somewhat commonplace in World Cup-level XC racing then, but with just enough movement to take the sting out of harsh impacts out back so riders could maintain traction and keep putting power down to the ground.

Courses have continued to get increasingly rougher and more technical, however, and so Trek has bumped things up a bit at both ends. The new Supercaliber is still very much a short-travel machine, but there’s now 80 mm of rear suspension and 110 mm up front – and the geometry has been designed to accommodate 100 mm or even 120 mm-travel forks.

As you’d expect, Trek is retaining the IsoStrut suspension design that defined the original Supercaliber. In terms of axle path, it’s a simple single-pivot flexstay layout with the swingarm pivot located just above the top of the chainring (and it’s now been raised to retain excellent pedaling efficiency with the 34-36T chainrings preferred by XC racers). But instead of resorting to a separate linkage to drive a standard rear shock, the Supercaliber uses a custom strut arrangement where the shock is a structural element of the frame.

Unusually, both ends of the rear shock body are rigidly fixed to the Supercaliber’s front triangle; it doesn’t move in any way whatsoever. The air can is integrated into the upper seatstay area, which slides along the rear shock body to form a sort of thru-shaft setup. Trek says the rear end of the Supercaliber is much more rigid in terms of bending and torsion than a more traditional design since there are no pivots, and it’s also theoretically lighter since there are fewer parts.

Perhaps also not surprising given the Trek Factory Team’s equipment sponsor relationships is a move from Fox to RockShox as the rear shock supplier. Shock stroke has grown to 40 mm, which lowers the leverage ratio so the system is more sensitive to small bumps, while the body diameter has increased to 38 mm to boost frame stiffness. Trek claims the new shock also bottoms out less harshly than before to make better use of the limited travel, and it’s supposedly easier to service.

You might catch that I included the word “theoretically” just above in reference to weight. That’s because, while eliminating all of that hardware should make for a lighter frame, the original Supercaliber wasn’t actually all that light compared to some competitors. Claimed weight for a medium Gen 1 frame was 1,933 g – light, but not crazy light. A later mid-cycle update added a UDH-compatible rear end and increased the frame’s strength, but raised the weight further to 2,050 g. That’s a lot heftier than Specialized’s 1,659 g S-Works Epic Evo, which not only includes all of those “heavy” extra parts, but also features a lot more suspension.

Trek has narrowed (but not completely eliminated) that gap with this update, bringing the weight of the top-end medium Supercaliber SLR frame-and-shock back down to 1,950 g. That means the Supercaliber still isn’t as light as some of its more conventional competition, but Trek would argue that the Supercaliber’s unique suspension and frame design offer enough of a competitive advantage to even the score.

Frame geometry has been updated, although the changes aren’t entirely in keeping with the whole longer-lower-slacker trend you might expect to see here. The new Supercaliber remains very much a dedicated XC racing machine.

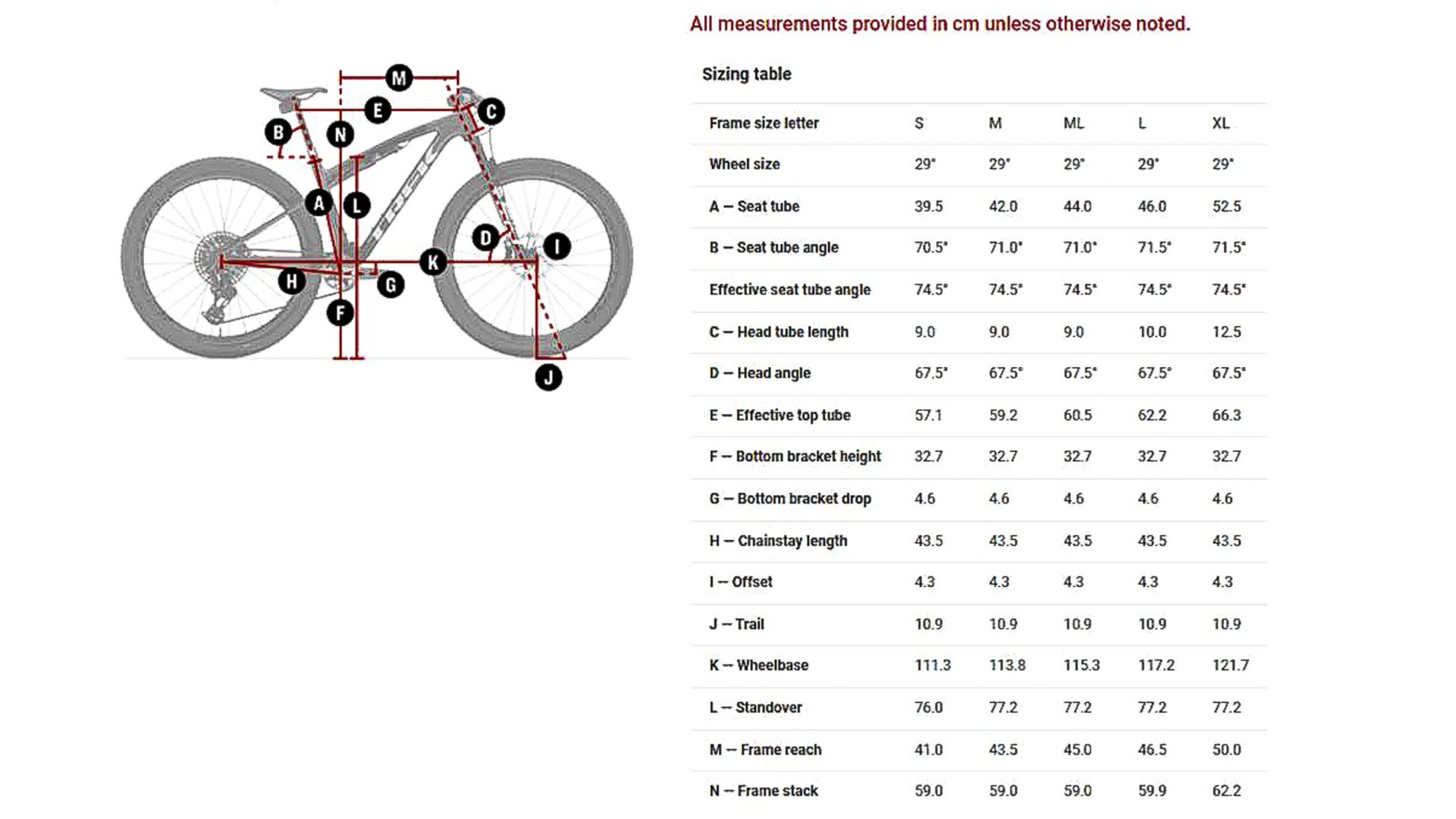

Head tube angle has decreased from the previously silly-steep 69° to a more reasonable 67.5°. According to Trek, the goal was to tone down some of the first-generation Supercaliber’s nervousness, but maintain its sense of agility. Reach has gone up, too, growing about 10 mm across the board to push out the front center for more stability and confidence at higher speeds and steeper descents – a clear nod toward modern World Cup courses. Also in keeping with trends, the seat tube angle has steepened, but only by 0.5° to 74.5° to accommodate the slightly more forward positioned favored by racers these days without overly compromising power production. Chainstays are five mm longer than before, which Trek says improved traction on climbs.

Ok, so it’s still longer and slacker, but the bottom bracket has actually been raised about seven mm to decrease the chance of pedal strikes. Stack height remains the same as before, so hardcore racers shouldn’t worry that Trek has turned the Supercaliber into a toned-down trail bike.

One thing you won’t find on the new Supercaliber? Headset cable routing. It may not be fully guided end-to-end, and still relies on foam sleeves to reduce rattling instead of a more convenient (but heavier) tube-in-tube arrangement, but hallelujah, this restores my faith in the bicycle industry.

“We prioritize assembly and serviceability of the bike for all of our customers: mass assembly, shop technicians, end user,” said Trek mountain bike engineer Alex Martin. “Housing is still visible with headset routing (brake lines) and servicing a headset becomes complicated. Additionally, the impacts to steerer tube and housing longevity is a concern.”

You’re my hero, Alex.

Models, prices, and availability

Trek is offering the new Supercaliber is seven complete models. Five are built around the top-end Supercaliber SLR frame, while the other two feature a new Supercaliber SL. That one uses a lower-end carbon blend in the front triangle that adds “200-250 g” relative to the Supercaliber SLR, but also adds tube-in-tube hose and housing guides for added convenience. The rear triangles are identical throughout.

There’s also a Supercaliber SLR frameset on tap for the DIYers, but conspicuously absent are any aluminum Supercaliber models, which Trek has no plans to develop given the complexity of the IsoStrut design. Also curiously absent – particularly on the top-end models – are stock power meters.

Here’s a breakdown of the different models. Keep in mind I’ve only shown a single color option in each model (there are two or three across the board), and only US pricing has been provided so far.

Trek sent a top-spec Supercaliber SLR 9.9 XX AXS for this test, built around the flagship SLR carbon fiber frame and outfitted with a laundry list of droolworthy bits: SRAM’s premier XX SL Eagle Transmission wireless groupset, silly-light Bontrager Kovee RSL 30 carbon fiber wheels wrapped with fast-rolling Pirelli XC RC tires, a Bontrager RSL one-piece carbon fiber bar-and-stem combo with an aggressive -13° angle, and a barely-there Bontrager Aeolus RSL saddle with a molded carbon fiber shell and carbon fiber rails sitting atop a Fox Transfer SL dropper seatpost.

Actual weight for my medium-sized tester without pedals or accessories was 9.70 kg (21.38 lb) – about 250 g heavier than claimed, but still very light.

Climbing like Superman on the Supercaliber

It’s long been said that one of the secrets to success on the harrowing cobbles of Paris-Roubaix is just to go faster, since you’d then only be skimming the tops of each stone instead of falling into the troughs. Easier said than done, eh? Well, the suspension of the Supercaliber feels a lot like skimming the tops, even when you can’t always go super fast.

The updated IsoStrut suspension doesn’t erase bumps like you might expect of something with more – and more active – travel, and comparatively heavy compression damping makes you fully aware of everything on the ground. It’s firm, but in a good way. But it effectively feels like you’re just clipping those tops, and it nearly eliminates the need to actively unweight the rear end on impacts like you would with a hardtail. It’s also impressively adept at maintaining traction through tricky corners.

Of course, even with the slight increase, 80 mm of rear-wheel travel still isn’t much, especially once you account for sag (I was running about 20% front and rear, FYI). However, what was most striking to me during my test rides was how effective it was, even on terrain that many might not consider to be traditional XC. But what the heck is “traditional XC” these days, anyway?

Drops from two or three wheel heights are practically the norm now at UCI World Cup XCO races, as well as more modestly sized doubles. So of course, I wanted to see how the Supercaliber would do in those situations (sorry, Trek). And quite surprisingly, it actually did pretty well. Naturally, you don’t get a soft and pillowy landing like you would on a longer-travel setup, but touchdowns are remarkably tame. The bulk of the impact has to be absorbed with your arms and legs, but there’s a startling lack of harshness.

Part of this may be related to the changes RockShox recently instituted on its latest-generation SID fork and SIDLuxe rear shock. I’d previously found both to be needlessly firm (particularly on smaller stuff), but the new damper tunes are much more supple than they used to be, without taking away from their efficient feel. Front and rear balance is spot-on, too. It’s still very XC-specific suspension, but the limited travel is now a lot more accommodating.

As the testing progressed, I found myself pushing the Supercaliber harder and harder, and on increasingly challenging terrain. Big chunky rocks? Steep and sketchy rock rolls? Surprise huck-to-flats? Basically, I stopped thinking to myself that I was on a dedicated XC race bike, and instead just rode it as I normally would just about any other trail bike. In that sense, the Supercaliber isn’t something I’d want to be on all day in those conditions – again, 80 mm of travel – but even after three hours or more, I found myself hopping off and shaking my head at how capable this little thing was.

It’s a similar story in terms of handling.

I should preface this next bit by saying that I never rode the first-generation Supercaliber and can’t comment on that bike’s characteristics. But that said, I can only imagine how twitchy that bike may have been given this new one is still plenty nimble despite the changes to the wheelbase, chainstay length, and head tube angle.

Make no mistake: 67.5° still makes for a very agile front end, but it comes across as pleasantly and intuitively darty here instead of nervous. It’s easy and fun to flick the front end around, and the rear end dutifully follows, even on tight uphill switchbacks.The high-speed stability was better than I’d expected, too. Crazy-fast two-track downhills can be attacked with abandon (assuming you’ve got good sightline for what – and who – might be coming up), and I never hesitated to take the random mini-wall rides or boosty side hits. And if pedal strikes were an issue before, they weren’t here.

We shouldn’t forget the Supercaliber is first and foremost a XC race bike, though, and it fulfills that duty with aplomb. In particular, it goes uphill like mad. The chassis is wonderfully stiff, and between the generous amount of anti-squat incorporated into the newly raised main pivot and the rear shock’s compression damping tune, there’s essentially no energy wasted even if you don’t bother to use the lockout. Climbing traction is superb even on the techy stuff, and when you add in the low weight, it almost becomes a joy to gain elevation.

But perhaps the most striking thing to me about this new Supercaliber is it’s just plain fun to ride. The limited travel does carry with it the aforementioned caveats, of course, but not nearly as many as I’d expected, and I’d suspect it’d suit a wide range of XC-type riders, even if they never attach a number plate.

Build kit breakdown

Trek didn’t leave much off the table when it came to outfitting the flagship Supercaliber SLR 9.9 XX AXS model I tested, and so it’s not at all surprising I don’t have too many complaints about any of it.

I’ve commented on several occasions in the past about the shift performance of SRAM’s new Transmission stuff, and nothing’s changed here. Individual shifts are incredibly reliable and positive – especially under full power – and as much as I continue to dislike how much effort is required to push the shift buttons (why are they so hard to push???), there’s a decent amount of adjustment so you can get them positioned mostly where you want them. Multiple shifts are still frustratingly slow, but I’m at least starting to get used to waiting. So be it.

This was another positive experience with SRAM’s Level Ultimate four-piston hydraulic disc brakes, too. They’re nowhere near as brutal as something like the more enduro/DH-oriented Code (or any of Shimano’s four-piston offerings, for that matter), but they’re also heaps lighter, much more powerful, and easier to control than the old monobloc-style two-piston Level brakes that came before them. Lever feel is pleasantly firm, too, the organic pads run quietly (they don’t even squeal much when wet), ergonomics are excellent, and perhaps best of all for home mechanics, there’s heaps of rotor clearance. And kudos to Trek’s product manager for choosing the shiny silver finish instead of black.

I’ve ridden the Bontrager Kovee RSL wheels before, but it’s still startling to hop on a set of mountain bike wheels that weigh as little as these do. Even compared to a typical lightweight set of carbon wheels, these are around 300 g lighter at around 1,200 g for the pair. That’s about two-thirds of a pound of rotating weight for those of you that prefer to think in freedom units, and that’s with a generous 30 mm inner rim width, too.

But yet despite the low mass, they still feel pretty solid even when pushing hard through technical terrain, and they’re anchored around dependable DT Swiss hubs. The startlingly low weight leaves me hesitant to really go smashing through rocks with reckless abandon as I typically do with my trail bike wheels (I’d recommend foam inserts in that case), but by and large, these are some of my favorites for straight-up XC-type riding.

The front and rear suspension is worthy of further discussion, too. Recent compression damper updates on the revamped SID SL fork and SID Luxe rear shock yield tangible improvements with noticeably more suppleness, especially off the top. They’re still appropriately firm, but now they don’t feel like they’re needlessly beating you up and are far more adept at filtering out the small-amplitude chatter that wears you down over time. And yep, the SID SL still features a less-stout 32 mm-diameter chassis as compared to the standard SID, but given the limited travel (and my modest 72 kg body weight), I didn’t find flex to negatively affect the bike’s handling precision.

I hope reliability isn’t an issue, though. While the fork and rear shock on my loaner bike worked fine during the several-week test period, the rear shock damper sprung a leak almost immediately, spewing a steady drip of oil right on to the nozzle of my water bottle (eww). The damper thankfully held on until it was time to send the bike back to Trek, but it wouldn’t have taken much longer before the damper started to lose significant performance as the oil foamed up. Well done on the new tune, RockShox, but let’s make sure these are all working properly, eh?

By and large, the mostly Bontrager finishing kit was very good. The one-piece Bontrager RSL bar-and-stem is very light at just over 200 g (total!), and it’s a good thing the angles agreed with me since there are no adjustments allowed aside from spacers to fine-tune height. However, the ride quality is quite stiff (cushier grips would have helped), and I would have liked to see a computer mount included to go with the proprietary mounting hole.

Out back, the Aeolus RSL saddle was a pleasant surprise. It’s extremely firm, being more of a road-derived model, but the smart shaping was still a comfy companion even after more than three hours on rocky trails. I can’t comment on the wisdom of carbon fiber rails for a mountain bike in general, but I didn’t have any issues this time around.

But why include a dropper seatpost on a dedicated XC race bike given the weight penalty and the focus on shaving grams? Because it’s one of those things that adds weight, but allows you to go faster overall. Kudos to the Trek product manager for including one here.

Trek Supercaliber vs. Specialized Epic World Cup: FIGHT!

Oh man, this is going to get ugly.

Specialized introduced the very Supercaliber-looking Epic World Cup just this past April, and the two bikes indeed look very similar at first glance. Both use nearly identical-looking rear suspension designs, and with 75 mm of claimed travel, the Epic World Cup trails the Supercaliber by a scant 5 mm; fork travel for both is pegged at 110 mm. Frame geometries are within a few millimeters of each other pretty much across the board, too.

There’s such strong resemblance, in fact, that the Epic World Cup was widely referred to as the “Specialized Supercaliber” by online critics. Yet despite the visual similarities, they’re very different on the trail – and at least to me, one is clearly better than the other.

In reality, the suspension designs don’t actually have that much in common. Whereas the Supercaliber features that distinctive IsoStrut layout with both ends of the shock body rigidly attached to the top tube, the Epic World Cup is fundamentally a linkage-driven flexstay design. The forward shock eyelet is attached to the top tube, but the rear eyelet is connected to the seatstay with a teeny, tiny swing link. The rear end of the Epic World Cup is theoretically less rigid as a result, although the difference isn’t so noticeable while riding.

What’s much more impactful is the shock tuning.

The IsoStrut layout may be novel, but the Supercaliber’s shock setup is utterly normal with 20-30% of intended sag and a self-equalizing negative air chamber. The Epic World Cup, on the other hand, is designed to run just 0-10% of sag with much less negative air pressure than positive pressure. The idea behind the minimal sag is to leave as much positive travel on hand when you really need it, except that the big positive-vs-negative pressure differential makes the breakaway threshold so high that the rear end just doesn’t move at all until you really smash into something.

In that sense, it’s good to have a safety net on a machine that otherwise behaves like a hardtail. But whereas the Supercal’s suspension pedals like a hardtail while also providing the usual comfort and traction benefits of a full-suspension bike everywhere, the Epic World Cup pedals like a hardtail, but also beats you up like one while offering minimal traction advantages. Further exacerbating the issue is Specialized’s so-called Brain technology. It’s designed to only open and activate the suspension when it senses impacts, and while it’s better than it’s ever been, it still isn’t as sensitive as more traditional valving.

Add in the fact the Epic World Cup is actually heavier than the more conventional full-suspension Epic, and it’s no wonder we’ve rarely seen the World Cup in competition under Specialized’s sponsored racers.

To be clear, this is exactly how Specialized intended for the Epic World Cup to behave. But it also reminds of a decades-old Giant NRS, and not in a good way. Dave Rome will have a full long-term review of the Epic World Cup posted soon, but long story short, to me this is a rare miss from the big S.

The Supercaliber is pretty super

I fully anticipated the redesigned Supercaliber would be excellent as a dedicated cross-country race bike. It’s light, it pedals extremely efficiently, the handling is spot-on, and the limited suspension travel is very well-tuned.

But what I didn’t expect was how well the Supercaliber would perform for XC-type riding in general. It’s a hoot to ride even when someone isn’t recording with a stopwatch, and it’s far more capable than its modest travel figures would suggest. It’s still no trail bike, of course, and while I certainly haven’t ridden everything in the category, my opinion stands that a properly skilled rider looking for a go-fast XC race bike that still offers a surprising amount of versatility could do a whole heck of a lot worse than one of these.

More information can be found at www.trekbikes.com.

What did you think of this story?