There’s no denying that interest in cross-country bikes has returned with a vengeance. Modern race courses are more technically challenging than ever, and to match that, the bikes have become the answer for anyone seeking a light, nice-pedalling, all-rounder mountain bike to head into the hills with. It’s a category that trail mountain bikes successfully held, until those got increasingly heavier and slower.

Having started with bikes like the Scott Spark, modern race bikes are now trending toward progressive trail bike-like geometry with 110-120 mm front and rear suspension travel. Add in the dropper posts and 2.35-2.4" tyres and these bikes are vastly more capable than XC bikes of old.

That brings us to Yeti’s rebirth of its dedicated full-suspension cross-country race platform—the ASR—a model that had been missing from the Colorado mountain bike company’s lineup since 2017. Instead, recent years saw Yeti fulfil its cross-country quota with the SB100, which morphed into the SB115. Carrying the weight of the company’s more complicated Switch Infinity suspension system, it wasn’t a platform you saw raced too often at the sport’s top end.

With the re-introduction of the ASR, gone is the Switch Infinity system from Yeti's cross-country platform. In its place, sits a familiar design that has helped to produce one of the lightest frames on the market today. I’ve been testing the company’s new flagship "Ultimate" version of the ASR, a top-tier version that also provided an opportunity to test out RockShox’s new SID Flight Attendant electronically controlled suspension package. And to tease of how this test went, I’ll just say welcome back to cross-country, Yeti.

Lows: A 30% sag number makes the lock-out a requirement, tall bottom bracket height, stock stem likely too short for some, yet another premium-priced bike.

Total weight: 10.43 kg (22.99 lb) (as tested, without pedals or cages, but with tyre sealant)

Complete bikes from: US$5,600 / AU$8,590 up to US$13,900 / AU$19,990 (as tested)

Returning to its roots

Yeti Cycles is no stranger to the pointy end of cross-country racing, and I certainly have fond memories lusting for the turquoise brand’s lightweight ASR (full suspension) and ARC (hardtail) bikes in the early 2000s. The first ASR came in 2001, and by 2003, the production version was running a linkage-driven and top-tube-mounted rear shock with a flexstay pivot at the back end.

Flexstay designs lost popularity for nearly two decades, but they are now wholly back in vogue. Merida, Specialized, Cannondale, Giant, Canyon, Santa Cruz, Cervelo, Pinarello, Superior, and others all employ a familiar flexstay design for their respective cross-country offerings. And as you may expect, the new ASR has returned to it, too.

Yeti claims that unlike many of its competitors using a similar suspension layout, its bike will fully utilize its claimed 115 mm rear wheel travel (more on this in the next section). In keeping with current trends in cross-country bikes, that travel is intended to be matched with a 120 mm fork up front.

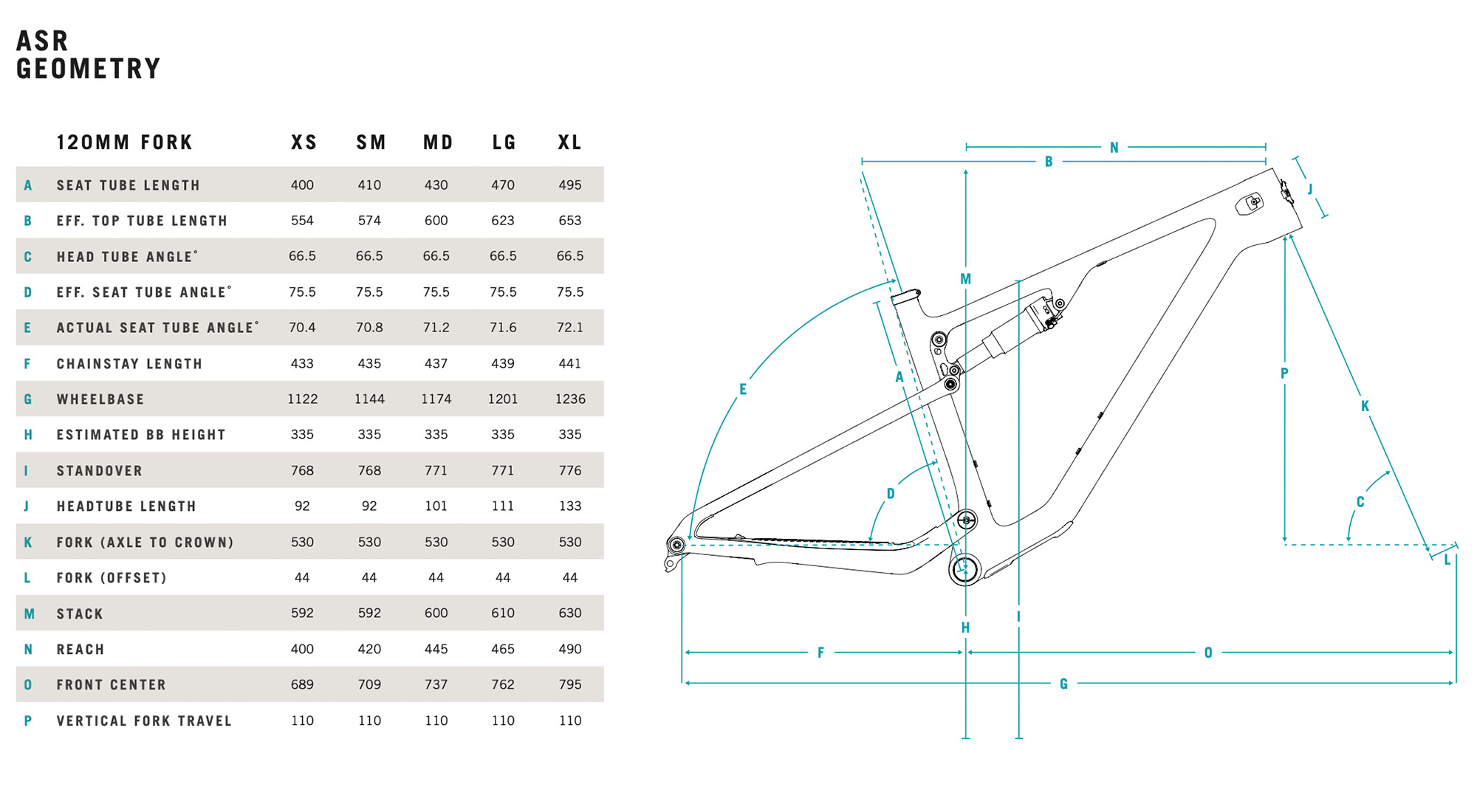

Matching that longer travel are some expected progressive geometry figures. Here the ASR aligns relatively closely with the figures of the equally new Specialized Epic 8 (at least with the Epic in its ‘High’ position geometry), although the Yeti is marginally shorter in reach. Across the five sizes (including an extra-small option), the ASR offers a consistent 66.5 head angle and 75.5 seat angle. Meanwhile, rear centre length (aka, chainstay length) grows with frame reach figures, something not so commonly seen amongst cross-country bikes.

As a premium carbon cross-country bike, you can bet the ASR has a light frame. According to Yeti, this new bike has the most sophisticated carbon lay-up in the company’s history, a likely hint of what’s to come for other bikes in the lineup. That lay-up isn’t so much about the specific materials used, but rather the shapes and orientations of the carbon plys. Meanwhile, Yeti claims to have paid close attention to putting all the main pivot points in areas that are already reinforced for other applications, such as the main pivot at the bottom bracket junction or the top pivot at the top tube and seat tube intersection. Further optimisations are done with each frame size having its own unique carbon lay-up and design; it's not a groundbreaking concept, but also not as common as you may think.

Like many of its other bikes, Yeti is offering two distinct tiers of the ASR. At just 1,830 grams for a painted medium frame (1,552 g without shock), the Turq – aka T-Series – is the lighter and more premium option. As Yeti’s lightest full suspension frame ever, it has a more advanced carbon lay-up that employs larger and more shapely plys in order to reduce material overall. Further weight is saved by forgoing the tube-in-tube (aka guided) cable routing through the downtube, rather that feature exists only in the chainstays. The T-Series frames also offer an impressively paltry rocker link that’s machined from 7075 aluminium and weighs just 78 g with its four bearings.

By contrast, the more affordable C-Series frame offers a simpler carbon lay-up schedule and the shock mounts to a heavier 6061 aluminium rocker. Assuming most riders will still be using mechanical cables with this frame, the frame adds the tube-in-tube cable routing for simple straight-shot housing installs and replacements. Yeti claims a C-Series ASR frame (medium, painted) weighs 1,985 g with a rear shock (without a remote lockout), and 1,727 g without the rear shock. Second-tier or not, it’s certainly a competitive weight.

To add a touch of confusion into the mix, there’s also a wireless version of the T-Series frame which is exclusively available with the flagship (most expensive) Ultimate complete bike (sorry, no frame-only option for this one). As the name suggests, this wireless version assumes the use of electronic gearing and so the driveside cable ports or rear derailleur cable routing through the chainstay are not provided – a detail that saves a further 104 grams over the regular T-series frame and makes it the lightest frame on the market with more than 110 mm of travel. While I typically try to avoid testing the most expensive option, I couldn’t help but call in the Ultimate version as it provided an opportunity to test RockShox’s new Flight Attendant suspension.

Rattling through some important features, all ASR models offer room within the main triangle for two good-sized water bottles. Many brands achieve such clearance through kinking the seat tube, but Yeti has kept its 31.6 mm seat tube largely uninterrupted to provide compatibility with really long dropper posts – most sizes come stock with a 150 mm drop, which is already pretty damn long for the category. Meanwhile, tyre clearance is equally generous with room to clear 29x2.4" tyres mounted on 30 mm width rims, a size that has become the new standard in modern cross-country racing applications.

The ASR keeps the cables external of the regular (and quality!) IS-type CaneCreek headset. Those cables are routed into the frame through Yeti’s bolt-up cable guides that offer a semi-sealed and tight-holding design, while the angle keeps cable rub at bay. Included with all bikes are some adhesive-type protectors, including a little mud flap to protect the main pivot and one to protect the downtube against rock strikes. In the centre of that downtube cover sits a small hatch for easy access to the cables (no difficulty fishing for the dropper housing on this one) – although to speculate wildly, this hatch potentially gives a battery compartment for the rumoured next generation of Shimano Di2.

Other neat features include a custom chain guide that bolts into the main pivot bolt. It’s an elegant solution and can be easily adjusted side-to-side with a chain installed. The two smallest frame sizes can handle up to a 36T chainring, while medium and up will fit a 38T bigdog. And yep, there’s a regular English threaded bottom bracket and SRAM UDH derailleur hanger. Overall, this is one simple bike to build and service.

Suspension things

Yeti’s re-entry into cross-country may visually appear to be a carbon copy of many other popular options (and a design the company is returning to), but the ASR offers a few differing details, largely centred around its 30% rear shock sag. And yes, that’s a big number in the cross-country world.

Speaking with the company’s engineering team, the goal was to create a race bike that felt more planted, controlled, and with more traction than many others in the category. Sitting deeper into the 115 mm of travel is Yeti's strategy to achieve this, while a decent amount of anti-squat (just over 100% at sag) is present to stop chain forces from pulling the bike even deeper into its squishiness.

In reality, 30% sag is a fair bit compared to the more typical 20-25% figures used by competitors (and about a million times more than the Epic World Cup), as a result, you can bet that Yeti understands the need for a lockout. As seen on the new Specialized Epic and a bunch of other bikes, the ASR employs RockShox’s three-position SID suspension that offers open, pedal, and lock compression settings from a Gripshift-style remote switch. Meanwhile on the top-tier version, such suspension control is automated via RockShox’s electric Flight Attendant.

With such generous sag you may assume there’s a highly progressive suspension curve to keep you from bottoming out, but again, Yeti surprises. Instead, the ASR is said to be highly linear (just 10% progression, claimed) in order to encourage the full use of the available travel and to retain a more consistent suspension feel. Rather, it’s through the short 40 mm stroke shock and the natural progressivity of a smaller-chamber air spring that Yeti aims to avoid harsh bottom-outs.

Worthy of note, the rear shock isn’t attached with a yoke-style linkage but is rather mounted to the frame with old-school binding barrels and bolts. Yoke designs have become popular in recent years as a means of saving weight and creating space for bottles, but suspension service specialists will tell you that such designs can put unwanted bending forces on the rear shock (in a vertical plane). And so while Yeti’s layout may look more dated, I appreciate knowing that shock durability will be better for it. Plus, there’s no threaded shock mount to stress about ruining.

Back to that big 30% sag figure. It helps to explain some of the geometry numbers, namely the relatively tall bottom bracket height. Once sagged, the seat tube angles will be less severe and the bottom bracket lower. I’ll come back to how this all actually feels and works on the trail, but I suspect many will be reading this and thinking it sounds ideal for a downcountry-style bike that may not see any race action. On that note, Yeti has tested the ASR with up to a 140 mm fork up front, and so this one can get more rowdy if you so choose (just beware of the negative impact on bottom bracket height and seat tube angle). Still, the Colorado mountain bike company does have the SB120 (130 mm front, 120 mm rear) for those seeking something more in the short-travel trail category.

A range of bikes

Despite many in the industry's fears of impending doom, Yeti clearly has high hopes for the ASR. At least for customers in the USA, four complete bike options use the T-Series frame and there are two complete options for the lower-cost C-Series frame. Additionally, there’s a choice of three frame colours for both the T and C-Series bikes. And then there’s the flagship T5 Ultimate Wireless (tested), which has its own unique two-tone black, silver, and turquoise paint that matches rather perfectly with the provided build kit.

The T-Series is also available as a frameset with rear shock and remote for US$4,000 / AU$6,190. This frame-only option is available in the same three main colours as the complete bikes.

Being a premium brand you’ll find common equipment themes throughout the range, and while I’m not usually one to list specifications, these do deserve coverage (specs listed are for the USA and may vary for other countries). Firstly, Yeti has fully committed to SRAM, with each build utilising RockShox’s SID three-position suspension. Similarly, all bikes feature a SRAM groupset of some variant, and SRAM Level brakes (180 mm front rotor, 160 mm rear).

More common themes are seen with 30 mm-width DT Swiss rims wrapped with Maxxis Rekon 2.4" EXO WT tubeless tyre on the front, and a Maxxis Rekon Race 2.35" EXO at back. CaneCreek headsets are consistent throughout, as is the yet-to-be-released, shortened-length WTB Solando saddle with Yeti branding. Even areas where it’s common to find generic parts are kept to big brands here, with ODI lock-on grips (or SRAM grips when the Twistloc suspension lockout is present), brand-name cockpits, and Fox Transfer dropper posts across all but the top-tier model.

The range starts at US$5,600 / AU$8,590 for the ASR C2, a bike that features RockShox SID Select suspension, DT Swiss M1900 wheels, SRAM GX Eagle 1x12 mechanical shifting, and a Fox Transfer SL Performance dropper post. Meanwhile for an additional US$1,000 / AU$1,400, the ASR C3 Transmission adds a SRAM GX Eagle AXS Transmission groupset. Both the C2 and C3 can be upgraded to RockShox SID Ultimate suspension with the SRAM Twistloc remote lockout for an additional fee of US$600.

With the lighter frame, the T-series bikes begin with the T2 at US$7,200 / AU$11,700. This one gets you RockShox SID Ultimate suspension with the Twistloc remote to control the three-position compression adjustment (open, pedal, and lock) front-and-rear. This model keeps things light with SRAM Eagle X0 mechanical shifting, RaceFace Next SL carbon handlebar, BikeYoke BarKeeper stem, and CaneCreek Hellbender 70 Lite headset (lighter aluminium encased bearings). The DT Swiss XM1700 wheels are solid, but an obvious place to shave a decent chunk of weight.

At US$8,600 / AU$12,890, the T3 XO Transmission is much like the model above, albeit with wireless electronic shifting and an upgrade to a Factory-level version of the Fox Transfer SL dropper post (at least for the USA).

At 10.7 kg, the second lightest (and lightest with a wheelset upgrade) option in range is the T4 XX1 at US$7,900 / AU$N/A. And no, that price is not a typo, it’s actually cheaper than the model before it. That’s because this one reverts back to SRAM’s lightest groupset option in the form of XX1 Eagle mechanical. It’s rare to see SRAM’s mechanical options still equipped, and I appreciate Yeti’s intent here.

Each of the three T-series bikes above can be upgraded to a yet-to-be-released version of DT Swiss’ XRC 1200 Spline wheels with lighter SRAM Centerline X-Rotors for a not-so-minor upgrade fee of US$2,000. At just 1,303 grams for the pair and with a 30 mm internal width, these wheels represent the first time DT Swiss will offer front-and-rear-specific asymmetric carbon rims (Swiss-made, too). They’re laced up with DT Swiss’ new Revolite spokes and feature an updated version of the company’s 180 hubs rolling on ceramic bearings.

The fancy new wheels bring me to the final bike in the range and the one tested, the T5 Ultimate Wireless. This one runs with the full gamut of SRAM beep-boop for a total of seven batteries before even adding a head unit. It runs SRAM Eagle XX1 AXS Transmission shifting and power meter (reviewed previously), a RockShox AXS Reverb dropper post, and of course RockShox’s new Flight Attendant suspension package. Factor in the new DT Swiss XRC 1200 Spline wheels, Race Face carbon handlebars, a titanium-railed version of the new WTB saddle, and even ESI Silicon grips, and there isn’t much left to do on this one but race it. And while it demands a hefty fee at US$13,900 / AU$19,990, it’s still $600 (or AU$4,000!) less than an equivalently equipped Specialized S-Works.

My premium tester weighs 10.43 kg (22.99 lb) in a medium size and without pedals. This seems high for a price-no-object build, but that’s just the direction mountain bikes have taken in recent years with bulkier tyres and heavier electronics (SRAM Transmission shifting and the AXS dropper aren’t light).

How it rides

It was not so long ago that the best bikes for cross-country racing felt deadly fast to pedal and required a deft hand to steer. Often I’d ride such a bike and think it was a good tool for the purpose of pinning on a number, but not something I’d want to ride leisurely on technical trails. Rather, the “trail," “evo," “downcountry," or “special edition” of those race bikes – versions that offered longer forks, wider tyres, bigger brakes, and a subtly more relaxed position – were better aligned to the style of bike I’d choose to ride away from racing. Today, the top-tier World-Cup-level cross-country bike looks awfully similar to a downcountry bike from only three years ago.

In this sense, the latest crop of cross-country race bikes can be challenging to review. Do I assume everyone buying such a bike wants what’s effectively a lightweight trail bike? Or do I rather assume that the person buying this bike isn’t racing on technical courses and, therefore, that the old-school efficiency-over-control approach is best?

Whatever may be right for you, it’s clear that the new ASR fits snugly into the category of race-ready trail bike. It’s light, stiff under power, and still nimble like a good race bike. Plus it ticks the critical box of fitting two water bottles. Yet, the geometry and deeper use of sag give it some unique, perhaps polarising, characteristics.

That geometry is comparable to some wonderful bikes. Speaking for the medium size I tested, the ASR gets so many things right in terms of handling, weight distribution, and seating position. It’s an impressively stable bike that doesn’t blink at steep descents while being short enough to weave through tight climbs.

I typically got on well with the fit and handling, and found the shorter position to give this bike a seriously playful manner. However, I do think many riders stepping off other performance-focused machines will find the combination of the stock 55 mm stem and the given reach numbers to feel too casual, upright, and perhaps rearward. I run a fairly upright position on my cross-country bike (upright positions have been a growing trend in cross-country racing for a few years), and yet, there was still a 20 mm deficit between the two when measuring tip of saddle to center of handlebar clamp. Thankfully a simple and relatively small change in stem length should solve this problem for almost everyone, and it’s easy to do given the conventional two-piece handlebar/stem.

Not so fixable is the relatively tall stance of the bike. On paper, the ASR’s bottom bracket height aligns with the hugely popular previous-gen Specialized Epic Evo. I too complained of that bike feeling tall; however, the Yeti does come slightly back to earth when accounting for its notably deeper sag. As a result, when you’re on the bike that bottom bracket height isn’t so obvious. However, it sure felt high in instances of trying to remount after botching a technical climb.

Elements like bottom bracket height are often a game of give-and-take. That higher stance makes the ASR laughably good at pedalling through rocky and rooty terrain without scraping a pedal. It also lets you tip the bike into some seriously steep trail features. Still, with cranks trending shorter (170 mm given as stock), I feel the ASR sits on the higher side of where it needs to be.

The good pedal clearance is hardly the only factor making the ASR so adept on technical climbs. With the bike sitting deep into its travel, it does an impressive job of keeping the rear wheel in sync to the terrain. On more than one occasion I waited for the rear wheel to bounce and break traction, but rather I was greeted with uninterrupted pedaling.

Much like many longer-travel bikes with an equivalent sag percentage, the ASR feels mushy and wasteful as soon as you pedal out of the saddle. It’s here that Yeti is well aware that this bike needs the three-position lockout control it’s fitted with. Simpler off-on suspension systems do exist, but when riding off-road, they force you to choose between oodles of traction and none. While not unique, Yeti’s approach is welcomed, and it means you have a middle setting for off-road climbing and fast pedalling sections without losing all the benefits of a suspension system. The downside is that your left hand is likely going to be kept busy between twisting the Gripshift-style suspension lockout control to keep the bike feeling efficient, all while also controlling the dropper. Thankfully the provided Twistloc controller is the best compromise for mechanical systems, and it’s arguably a big reason for why we’re seeing RockShox’s SID 3-position suspension on so many new bikes.

That said, the best answer to this conundrum is to sell a kidney, car, cat, or first child and buy the Ultimate version as I tested. The provided RockShox Flight Attendant suspension takes what’s otherwise a hands-on suspension experience and turns it into a bike that thinks for itself. Dare I say it’s transformative to how much I enjoyed my time on this bike, and it wholly solved any questions over whether the ASR pedals efficiently in its open compression setting. Even after I turned off the auto-mode in order to control the suspension with the left pod shifter, I still found myself in awe with the effortlessness and speed of the lockout action.

I’ve recently shared my praises and criticisms for RockShox’s new Flight Attendant, and so I won’t rehash that. Still, for those who want the synopsis, I truly love what Flight Attendant does to this bike, but just be warned that it’s not always perfect, and it absolutely slants more toward the racer than the trail rider.

Of course, anything but the top-tier model will be back to manual lockouts, and it’s worth noting that Yeti aren’t at all alone in this complaint. Many bikes on the market feature remote lockouts, and a fair number of those need the rider to use them regularly. With cross-country bikes increasing in travel this issue simply isn’t going to disappear, and while I don’t love it, I think the eyesore and multi-tasking of remote lockouts is the new norm (at least when electronic suspension is financially unattainable).

Ok, rant aside, that 30% rear sag (12 mm on the shock shaft and 185 psi for my 70 kg weight) does bring benefits, and the ASR absolutely gorges itself on high-speed trail chatter. This bike is impressively smooth at speed, and when pushing the pedals along fast-yet-rough sections, it allows you to keep uninterrupted power flowing. Seemingly, the more chattery the terrain is, the more efficient the ASR becomes.

It’s also impressive how easily this bike uses its full travel without ever giving feedback that you’ve used the full travel. I won’t use the tired cliche of saying it's bottomless, but certainly no thunks, clunks, heavy spikes, or the feeling of hitting the floor were ever experienced. It’s not that this bike is forever kissing the end of the shock, but rather medium-sized jumps and drops are seemingly enough for the sag o-ring to near the edge.

And then we get to the frame itself. Visually the minimalist rocker link and slender stays lead your eyes to believe that the front and rear triangles would flex independently of each other, but looks can be deceiving. I was blown away by how much stiffness Yeti is achieving in such a minimalist-looking frame, and all while not having it feel like a rattle-can. Seemingly they’ve done incredibly well in lay-up department and the ride quality of this feels like a well-refined machine.

An Ultimate spec

I suspect most looking at this bike won’t be buying the tested Ultimate version, but still, there are some broad themes of the specification worth covering – namely the use of all big-name and proven items at a time when most brands have moved to using house-brands that provide better profit margin.

There isn’t a single weak area in how Yeti equips its bikes. Sure, the full suite of SRAM components may not be exotic or all too exciting, but they’re at least proven and functional. The XX SL Transmission is something I’ve reviewed before, and while my colleague James Huang has complained about it being slow to do multiple shifts, I still believe it’s the best shifting system currently on the market for carefree race use. The provided XX SL power meter is equally brilliant, although strong riders will want to swap out the provided 32T chainring for something bigger. Meanwhile, the provided Level Ultimate brakes on my sample are the old version, and while they work fine, I do think the four-piston versions are worth the minor weight gain.

Where I am excited is in the easily overlooked parts; things like a quality Cane Creek headset are now a rarity, but add greatly to the ownership of such a bike. The BikeYoke seat clamp is impressively light and goes unnoticed. And I have similar praise for the stock Maxxis tyres (a combo I’m well familiar with), carbon Race Face handlebar, and cushy WTB saddle. It’s been a long time since I reviewed a mountain bike where I didn’t feel an urgent desire to change at least one part, so kudos to Yeti for ticking that box.

Of course, things like stem length will remain subjective, as will the correct length of dropper post for cross country. Yeti equips trail-friendly 150 mm length droppers on its medium-XL bikes (125 mm for the smaller two options), and for many trail riders, the more drop the better. However, when racing, dropping the post is effectively like doing a squat, and as the available drop increases, you either end up doing a deeper squat or fighting against the motion of your body weight. It’s for this reason that you still typically see 100-125 mm droppers used in cross-country World Cups, while more casual riding typically benefits from bigger droppers. I won’t say whether Yeti’s choice here is good or bad, but it’s one to be mindful of if you take your racing seriously.

Finally, we come to the new DT Swiss XRC 1200 Spline wheels, which aren’t officially official yet. I’m quite smitten with their low weight, smooth ride quality, and knowing they’re easy to service. However, loading the wheel sideways does reveal some occasional spoke creak (rear wheel), and experience tells me that such noises tend not to improve with age. These are seemingly very good wheels, but I’m eager to see if the full-scale production version solves the spoke rub.

And I can’t end this review without praising Yeti for how well the basic colour scheme of my tested Ultimate Wireless ties together. The matte and gloss black look good, and with the gloss being used in high-rub areas, there’s a high chance this paint can be kept looking fresh. Add in the matching silver graphics that tie the suspension and wheels together, plus the complete lack of flappy cables beyond the brake hoses, and it’s a classy-looking bike.

ConfYeti

Yeti has a reputation for being a premium brand, and so I was pleasantly surprised to see that its complete bike options are competitive with a number of other popular (though not cheap) bikes in the category. Sure the Ultimate Wireless version tested is big-big money, but look to any of the models and you’ll see a brand that’s trying to sell its bikes on merit, rather than name alone.

The ASR will best serve anyone seeking a more planted, controlled, and perhaps relaxed (at least with the stock stem) ride out of a lightweight machine. It feels like a trail bike in times of need, but point it uphill, and it’ll remind you of its intent. And if you hate pedal strikes or fighting for traction, you’ll likely love this one even more.

I’m wholly sold on this bike when equipped with Flight Attendant, but I’ve never loved the constant switching of manual cable lockouts. That generous sag certainly brings benefits, but it also demands that you use the lockout if you bounce your weight while climbing, and even more if you like to climb out of the saddle. For this, I don’t think it’s the best choice for those living and racing in smooth terrain (unless, Flight Attendant), but rather one for those who regularly find themselves on rocks, roots, and generally technical terrain.

In riding the ASR I was constantly reminded that the latest crop of cross-country bikes have reached a point where they’re truly just brilliant mountain bikes that extend well beyond the purpose of squeezing into Lycra, pinning on a number, and drooling on your stem. These bikes can surely go fast, but likely more important to many, they’re damn fun to ride.

Gallery

Did we do a good job with this story?