Any member of the elite club of pro cyclists who have ever worn the yellow jersey of the Tour de France is familiar with the euphoria of putting it on. Many know the agony of losing it. Fewer still then come face to face with the desperate chase to beat the time cut and stay in the race to finish in Paris. Alex Stieda is the only one who has ever experienced those highs and lows in a single day.

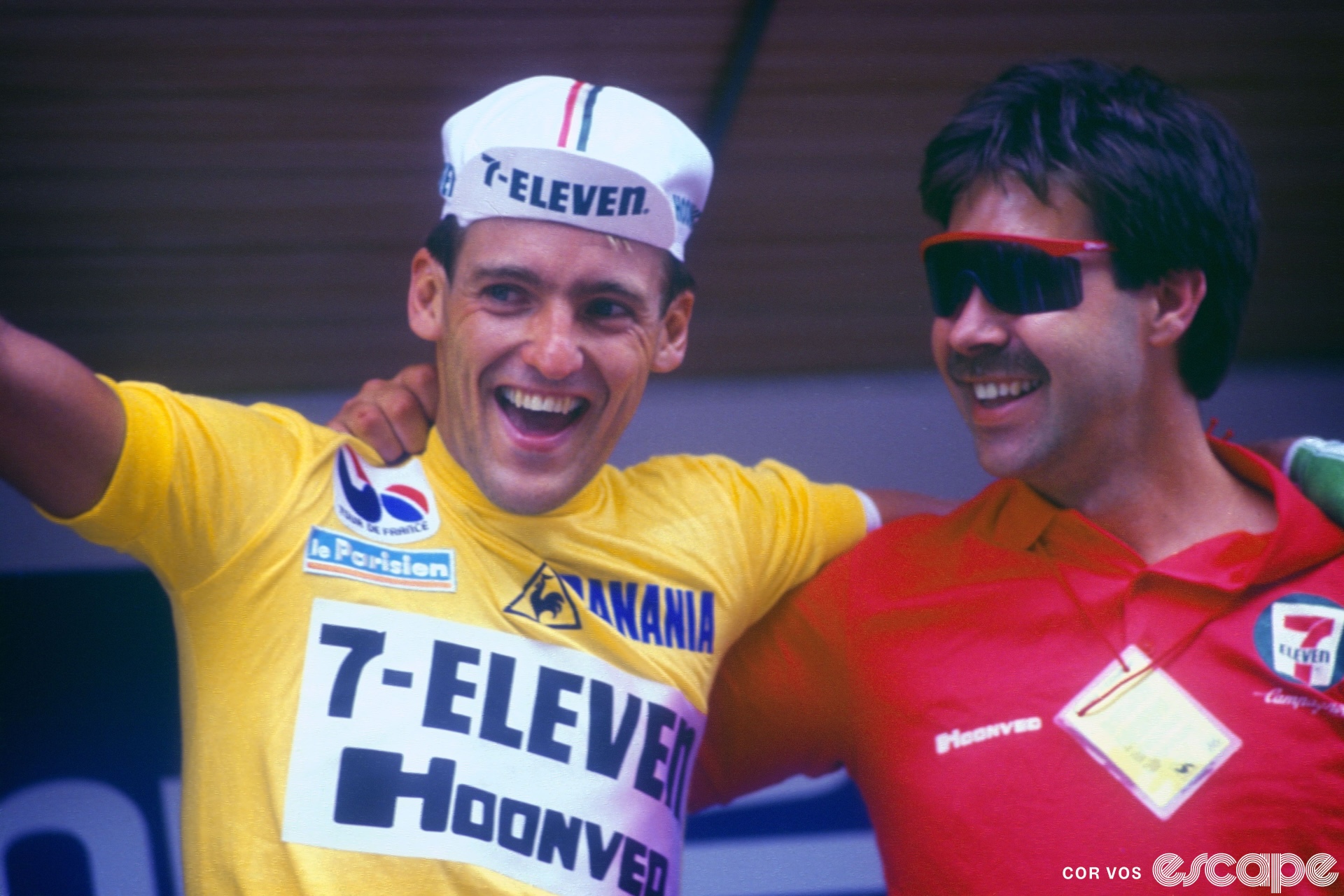

On 5 July, 1986, the Canadian rider, then 25, heralded the 7-Eleven-Hoonved team’s debut in the Tour de France by claiming the yellow jersey on stage 1, becoming the first North American to do so. As it turned out, that was only the start, as his daring raid put him in the lead of practically every jersey competition in the race.

But that day was one of the Tour’s old split stages, and stage 2, a team time trial, followed that afternoon for the inexperienced American team. By nightfall, Stieda had not only lost his prized jersey but fallen to 116th place after coming desperately close to missing the time cut, which would have put him out of the race entirely. “It was a surreal day,” Stieda tells Escape Collective from home in Edmonton, Canada.

Stieda, now 62, today splits his life between the roles of a married father of two, a career in Information Technology (IT), and organising bike tours and events. But when he looks back on that 1986 Tour, he does so with no lament that his half day in yellow did not convert to the fame and financial greatness that other riders have experienced for such a feat; nor that the 1986 Tour would be his only start in the great race and that his racing career in Europe ended soon after.

Significantly, his experience as a professional cyclist also equipped him for far bigger challenges to come, especially when diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2021, from which he has since recovered.

An unexpected yellow – and everything else

When Stieda raced the prologue of the 1986 Tour in Boulogne-Billancourt on the outskirts of Paris, he drew on his experience and power as a track pursuiter, placing 21st to position himself well for a daring attack the next day on stage one from Nanterre to Sceaux.

As the peloton eased into the early kilometers of the first road stage, Stieda simply rolled off the front. Once out of sight, he then soloed away until five other riders eventually joined him to form a six-strong breakaway.

“It was the first road stage … the peloton was going slow. Everyone was nervous and I thought, ‘I’m going to try something,’” Stieda says. “I was wearing a skinsuit. Everyone was laughing at me; but it was an 80 km road stage, and I knew I didn’t need any pockets for food.

“So, I just rolled up the road as if I was going to take a pee. Then, when I looked back and couldn’t see the peloton, I just dropped it into the biggest gear I had – a 53×12 – and went as hard as I could,” Stieda recalls. “We didn’t have race radios then. So, everyone relied on the chalkboard guy; and by the time the chalkboard guy took my time and dropped back to the peloton, I had three minutes.”

But Stieda, whose skinsuit should have been a sign of his intent, was not out for the win. “From looking at the road book, I knew that there were five sprints in 80 kilometers where you can get 12 seconds for every time bonus,” he says.

“I realized I could probably get some of these time bonuses and move myself up on GC. I knew I could be first; well … in the back of my mind I did because I put on a skinsuit. I knew I was going to try to get away, and that was the only way we knew how to be aero then.”

As the five-rider chase group closed in, Stieda charged on, fueled by encouragement from his 7-Eleven-Hoonved sports director, Mike Neel. “Mike was like, ‘Keep going, Alex, there’s a group coming, but you’ve got to get to the next sprint,’” Stieda recalls. “So, I took my hairnet off – in France at the time, you didn’t have to wear a helmet, or a hairnet – and threw it into the car. I could be more aero without it.”

Ultimately, he took three intermediate sprints while out alone, snaring 36 bonus seconds, but he still wasn’t sure where he was on virtual GC. It wasn’t until he was finally caught by the chasers that he learned – from Panasonic’s Phil Anderson, who was now in the break with him – that he was the overall leader on the road. Hence, Stieda worked tirelessly in the group to help it stay away and fend off the rider nearest on the general classification who might threaten his lead: Anderson’s teammate, the Belgian sprinter and Classics specialist Eric Vanderaerden.

“I started to realize if Vanderaerden [in the peloton] catches us and wins the final sprint, that because he had finished second on the prologue [at the same time as winner Thierry Marie], he would get a larger time bonus for the finish, and could potentially leapfrog me on time,” he says of how the tactics unfolded. (He didn’t know Vanderaerden had also taken bonus seconds at several intermediate sprints.)

Which breakaway rider took the win mattered far less to Stieda than making sure it didn’t go to Vanderaerden. “So, I made it my mission to try to keep the break going,” he says. “Then we got to 30k or 20k or 10k out and the guys are looking around, [thinking] ‘Who’s going to win the stage?’ There would be a guy attacking and then the rest are looking at each other not chasing.

“So, I would get to the front and drill it as hard as I can to bring this guy back. But of course, then no one rolls through. Then another guy attacks and I chase again. I probably did that four or five times, just burying myself to keep the group going. I didn’t care about winning the stage. And it worked. We turned the corner and there was a false flat to the finish for 500 meters. It was the longest 500 meters of my life … there’s nothing like looking back on a big wide boulevard and seeing the peloton sprinting from behind.

But it worked: while Stieda didn’t contest the breakaway sprint, won by Pol Verscheure, he finished two seconds clear of the chasing pack. He held off Vanderaerden – who picked up 18 bonus seconds himself on the road – by eight seconds in the general classification. “I finished fifth on the stage and I was just so fucked, like I was done, and thinking that this is [just] the first road stage of the Tour de France!”

But Stieda’s “who dares wins” attitude paid off in a way no rider has ever accomplished since. He not only claimed the yellow jersey that was his main objective; his aggressive approach also meant he took the polka-dot KOM jersey, the red points jersey for intermediate sprints, the mashup “combination” classification jersey (discontinued after 1989), and even the white jersey for best young rider.

No one was happier than 7-Eleven team manager Jim Ochowicz. “You have got to put yourself in Och’s shoes,” Stieda says. “He had risked everything, promised to the Southland Corporation that owns 7-Eleven, ‘You’re going get all this exposure … blah, blah, blah’ and they didn’t [even] have stores in Europe. What was their gain? It was all about the content they got for one hour on Sundays on CBS.”

The shirt(s) off his back

Despite their joy, Stieda and 7-Eleven-Hoonved couldn’t fully celebrate their success post-stage. After a few hours respite in a university gymnasium where all the peloton rested on camp beds, they all had to suit back up and race stage 2, a 56 km team time trial from Meudon to Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines.

“Because we were first on the GC, we were last off for team time trial which was good. It gives us a little bit more time to recover,” Stieda says. But the team had not anticipated riding with all eyes on them as the race leaders. “We had done no recon of the team time trial course,” Stieda says. Partly because of Stieda’s extensive podium ceremony duties, neither Ochowicz nor Neel had time to drive the course, and the riders hadn’t checked it out either. “We got the roadbook two days before. We were just going in blind.”

To make matters more difficult, Tour teams in those years were 10 riders. “An extra two guys make a huge difference going through turns, keeping it in line and coordinated,” Stieda points out. “And we hadn’t trained as a 10-man team. Few of our guys had done team time trials; [there was] a four-man team time trial for the Olympics, but that’s a whole different beast. So, our team time trial was just a gong show. It was complete chaos.”

It started off OK – rolling fast, everyone in line and smoothly trading turns. But then, at the end of a false flat downhill, in their biggest gears and racing flat-out, there was an unexpected T-intersection.

“It was straight, then suddenly the lead motorcycle turns left,” recalls Stieda. “We’re yelling, ‘Right!’ then ‘Left!’ then in the middle of the turn is a traffic island. The front guys, Ron Kiefel and Davis Phinney, were better at criteriums like I was, so, we went inside. The others went on the outside into the grass. Eric Heiden followed inside, but he was too heavy, hit the curb, went over and crashed.”

Because it was still early in the stage, the team slowed to regroup, but the momentum was gone. Cohesion began to break down too, when 1984 Olympic road champion Alexi Grewal earned the wrath of a teammate (who Stieda prefers not to name) for his line around a corner, for which the teammate chucked a full water bottle into Grewal’s back.

“The bottle explodes. [Grewal] looks back and starts screaming,” Stieda says. “We’re having this argument on the run.” But Stieda had a different problem: he’d spent 80 km in the breakaway earlier that day. “We got to 15-20 km to go. I’m shattered. I couldn’t stay on the wheel. Mike Neel says, ‘Jeff Pierce, Chris Carmichael. Wait for Alex and ride with him.’

“He pulled them out of the line, while the rest rode down the road to try to get a time. The three of us did our best to finish and made the time limit by 30 seconds. We could have gone home, after two days.”

The atmosphere at the 7-Eleven dinner that night was mixed, to say the least. Did they celebrate a terrific day, or commiserate a fall? “We were definitely on a high, having won the yellow jersey and ridden a team time trial in the yellow jersey,” Stieda recalls. There was a giddy, disorienting whiplash, “from, ‘Did this really happen?’ to, ‘What the…?’”

After being dropped by his team, Stieda lost yellow, the white jersey, the intermediate sprint points jersey, and the combination classification lead. But he still had polka dots.

“The next day it was like, ‘Let’s keep going … Can you guys help me get to the front and be there when there’s a hill to go for points?’” He did, and successfully scored a few to pad his lead. But that wasn’t all. Phinney managed to get in the move too, and when it split the American sprinter made the front and scored the stage win – another first for the American team.

Stieda’s loss of the yellow jersey was consoled by the team’s strong showing, including his defence of the polka dot jersey for the next four stages. But there was an underlying purpose in the ensuing days: to finish the Tour and prove that his yellow jersey was not a lucky fluke, but deserved.

That purpose was reinforced by the words of several seasoned professionals during his half day in yellow, including former two-times Tour runner-up and 1975 World Champion, Dutchman Hennie Kuiper. “What these guys told me was, to prove that I was worthy of wearing yellow, I had to finish the Tour,” Stieda recalls of their conversation. “So all I could think of was finishing. We didn’t have a GC rider to work for. We were hanging on every day. You would look up the road and there were Panasonic guys trying to drive and split the race. We were like, ‘That’s not us.’”

Stieda says his most challenging day was stage 18 from Briançon to l’Alpe d’Huez, which included the Col du Galibier, Col de le Croix de Fer, and the last climb to l’Alpe d’Huez where La Vie Claire teammates – yet also archrivals – Greg LeMond (who led the Tour overall) and Bernard Hinault (the defending five times Tour champion), finished together holding each other’s arm aloft, with Hinault credited with the win.

“That was one of the hardest days of my life,” Stieda says. Where LeMond was putting the finishing touches on becoming the first American win the Tour, Stieda placed 126th, 26:08 behind and again fighting the time cut. “I just dug deep. I said, ‘I have to keep going. I have to finish this Tour.’ The words kept ringing in my ears. I had to prove I was worthy of the yellow jersey.”

A short Euro career, a lifelong love of bikes

Stieda did finish – in 120th place overall out of 132 finishers, and 2:19:47 behind a victorious LeMond. He never rode the Tour again, and rarely raced in Europe until his retirement in 1992, opting to focus on the US circuit with 7-Eleven until 1990, then with the Evian-Miko and Coors Light teams for one year apiece.

“It made me realize where I was needed as a pro,” Stieda says. “You need to realize where you can add the most value. I was very pragmatic and realized from growing up playing ice hockey, racing crits and shorter road races in the Pacific Northwest, that with my background from racing track and focusing on track a lot, I didn’t have a lot of deep road racing experience for those longer stages.

“Over 200 km, I just couldn’t do anything. I knew I could be useful for the team. They still needed guys to race in North America. That’s the decision I made: to focus on races I could win.”

His experience in that Tour still helped to open doors after retiring. He first worked as a sales manager with the bicycle manufacturer Softride, became the co-founder of the Tour of Alberta stage race – which ran from 2013-2017, and ventured into cycling tourism and television as a cycling pundit.

Through his love of the bike, especially gravel riding, and in between his work in the IT industry and family commitments, Stieda created the Festivus of Gravel in Edmonton, Alberta. The first edition was held on August 17. Its aim is to raise awareness and funds for the University of Alberta Hospital in the fight against prostate cancer, which he faced and has since beaten.

“It is one of the most common male cancers,” Stieda says. “No one talks about it. It’s like an underground thing no one wants to bring into the open. So, I started the event, partnering with the hospital’s foundation to raise awareness for early cancer detection.” It also helps him spread a message he encourages others to embrace, especially those battling the disease.

“Going through prostate cancer gave me a bit of a wakeup … about what’s important in my life, and my wife (Samantha) and two grown kids (Kalie and AJ),” Stieda says. “It’s not all about me … but a bigger picture. Having my wife by my side the whole time was amazing. She was so supportive and she there with me every step of the way.

“But I also leaned on my experience as a cyclist and professional athlete. I’ve been through a lot of hard times. If you just keep putting one pedal stroke in front of the other you usually get through stuff.”

Did we do a good job with this story?