For the most part, there is a big difference in how our dear Escape Collective members ride and think about bikes compared to the rest of the general population. You guys are, in the grand scheme of things, the hardcore. Real two-wheeled acolytes. It’s a hobby, a passion, something you invest your valuable time and money into.

For many others, it’s more perfunctory. Simply a means of getting from A to B that avoids traffic, is cheap, and far less soul-destroying than getting on a bus or driving a car for your morning commute.

One of the beauties of the modern world is that many cities now have public bike-sharing schemes, where in return for the change in your pocket you can experience a place in the most efficient, enjoyable way possible: by bike.

There’s something about seeing a foreign city by bike that makes you forget you’re a tourist there. A chance to peer into how the people who live there actually live. When walking around it’s painfully obvious you’re not “from here.” You gawp up at buildings you’ve never seen before, a child-like wonder visible on your face while everyone else looks straight ahead or down at their phones, passing views they’ve seen a million times before. The bike is more of a leveller – you have to keep at least one eye on the road, just like every other cyclist around you.

With all of the new-ness comes a pressure to observe as much as possible. To be gluttonous for fresh sights. To maximally consume the place you find yourself in. That’s another reason why the bike is king: instead of walking until your feet hurt, suddenly you can cover four or five times the amount of ground in the same time.

So, having found myself in East Asia post-Guangxi for a little off-season jaunt, seeing as there are no races in the winter to keep me tethered to a European time zone, it was time for a redux of my honest review of riding four cities in America at The Old Place last year with a knee-jerk, licked-finger-in-the-wind review of what it’s like to ride bike-share schemes in four of the biggest and best-known cities of East Asia.

Seoul searching

After a couple of days in Seoul being accosted by the bright lights of the Hongdae party district and the hordes of people younger and better-dressed than myself, it was time to find some backwaters, to see how regular Seoulites live.

As long as you have 2,000 won (US $1.50) to feed into the ticket machine and the patience to then go and get your 500-won ticket deposit ($0.37) back from the refund machine, the Seoul metro line makes the city your oyster. While metros are usually very convenient, you don’t get to see or experience all that much. So I headed east to the Jungnangcheon tributary to ride the bike path south until this river connected up to the Han river.

But along the banks of these waterways is the sort of leisure-activity haven that at least this citizen of Small Rainy Island’s Capital City could only believe exists in my wildest socialist utopian dreams.

Grown men are busying themselves with a weekend game of baseball, parents hit tennis balls with their children, people tend to allotments (community gardens), and – running past it all at a maximum allowed speed of 20 kmh – the city’s cyclists.

Although, it is hard to tell how far or how fast I’m going. The “Seoul Bikes” bikes aren’t … optimally set up, let’s say.

Firstly, the maximum height of my seat still left my knees drawing tight circles in the air; coupled with the classic heavy feel of a bike share scheme-bike designed to withstand anything an entire metropolis could chuck at it, both colluded to ensure this was a proper work-out.

The great and the good of Seoul’s road cycling community zip past in Pas Normal jerseys and expensive bikes, but others are just out and about to enjoy the Sunday sun. I heave the bike up twisting and rising corners, battle the headwind through curves in the path and under low bypasses. But it’s still a genuinely good time and, maybe this speaks to the sadness of my home society, it’s a truly public good that is being cherished and used by the people it was built for. There is a glow to everyone’s day of rest, barely a Sunday Scary in sight. Only joy and relaxation. I would have paid a price much dearer than the 2,000 won ($1.50) it cost for my two hours of riding. There are 2,600 Seoul Bike stations in the city, and when it costs the same as a ride on the metro, it becomes a question of preference. However, if you live here and want a year-pass? Only $30. $0.08 a day. This is what a real country looks like.

Osaka living

Apps are tricky. Apps in different countries are tricky. Apps in different countries with a different alphabet to the one you’re used to are perhaps the trickiest. For all of the physical drawbacks of Seoul Bikes, you could easily download the app, press a few buttons and bingo, a back wheel lock popped open and a speaker on the rear wheel’s plastic casing said something likely important to me in Korean that I didn’t understand. But I was off and pedalling in less than 10 minutes.

Having flown into Fukuoka in the very south of Japan late and spent a night in a hotel room where over 1,000 cigarettes had been smoked in its dilapidated lifetime, I had hoped to puncture what was inevitably a sobering trip to Hiroshima with a ride to take in a city that was erased from history less than 100 years ago and has rebuilt itself entirely save for the wrought-iron dome that pulls the sprawl towards it like gravity. Of course, Hiroshima is awash with tourists from the West, which in of itself makes you feel a bit weird. It’s instructive, though, in that we (and the things done in our name) are often the bad guys.

A quick Google hinted at the existence of a bike share scheme but in reality it was nowhere to be seen. Google Maps, or at least English-language Google Maps, displayed bike stations that didn’t exist. And anyway, the mish-mash of VPNs, Japanese SIM card, and English phone conspired to make the App Store say: “Yeah, not sure about this” and so I couldn’t download the docomo app to double-check anyway.

Next stop: Osaka, and a second option at a bike share app! Here we go, the optimistically named “HELLO CYCLING,” yet technology failed me (or more likely, I failed it) once again. Luckily, the docomo gods were looking down favourably and amidst the hundreds of docomo stations where bikes are only available via the app, there are two where you can physically buy a pass in order to use the bikes.

A 25-minute walk to the north-east corner of the city leads me to a cafe with a row of red bikes sitting out front. A woman comes out and points me further down the street. On a random door is a docomo logo. Inside are two men sat either side of a big table in what looks like an office. I make the universal motion for bike, moving my hands as if they are my feet turning the pedals. He runs into a bike room and produces a small woman with perfect English, who then quickly produces a form, takes my 2,000 yen ($13) and I finally have a day pass to ride an elusive docomo. I am now the proud owner of a physical docomo card, that if I return to them will relinquish a 500-yen deposit, “but you can bring it back today, a year from now, or in more years,” I am told.

As the very helpful docomo gatekeeper watches on with slight concern, I pedal off down the street. The first thing to say about the red share-bike is that it’s electric, which means a slight press on the pedal gives me a gentle push in the right direction, the culmination of a primordial journey from the very first atom via my ancestors discovering fire to me getting some electrified help that will make my bike trip less tiring and sweaty. That’s progress, people.

The second thing to know about the bike, Dutch-style but smaller, is the narrow handlebars and resulting small turning circle, which makes it much more fun and nippy. No more reversing on tip toes like you often see with lost tourists mid-ride (although, again, the seat doesn’t go up enough to produce optimum comfort). It’s a more expensive offering but undoubtedly worth the price. I am not battling this bike, we are tearing through the city, one gentle push-off from a red light at a time.

Building upon the delight of my ride in Seoul, I head for the river banks, and another quick search produces information of a 5 km loop incorporating a waterside bike path. Once more, it’s great fun. There are men in pinstripes playing baseball again, but it’s not quite the utopia of the Jungnangcheon tributary.

The key part of riding in a city that isn’t your own is to copy what the locals do. Invariably, you’re going to do something wrong, unknowingly break some unwritten rule, but the risk of offending is vastly reduced by mirroring what you see others doing. The road coming up turns into a one-way street, so you dive onto the pavement like the cyclist you’re following. You don’t get into trouble but that could also be a factor of people’s politeness.

The true renegades can be spotted at pedestrian crossings, where the vast majority wait patiently for a maddeningly long amount of time for the lights to change even if there is no traffic coming, save for the solitary non-conformist individual who will cross the road as and when they like. Big respect, but it would be rude if I followed your lead. The other noticeable rigidity of rule-following is on trains, where everyone sits in their reserved seats, which led me to be trapped in by a larger businessman en route to Osaka despite 90% of the carriage being free. This wouldn’t have been that much of a problem had he not spent the entire hour-long journey staring at the same naked photo that had been texted to him. If it was his partner (and I pray to all of the gods for various reasons that it was) I hope they know he loves them very much.

Kyoto calling

At the end of my 50-kilometre, 15-minute bullet train ride from Osaka was Kyoto. Despite being a more traditional, historic offering when compared to the likes of Osaka and Tokyo, the bike-share system of the former capital is a springboard into the future.

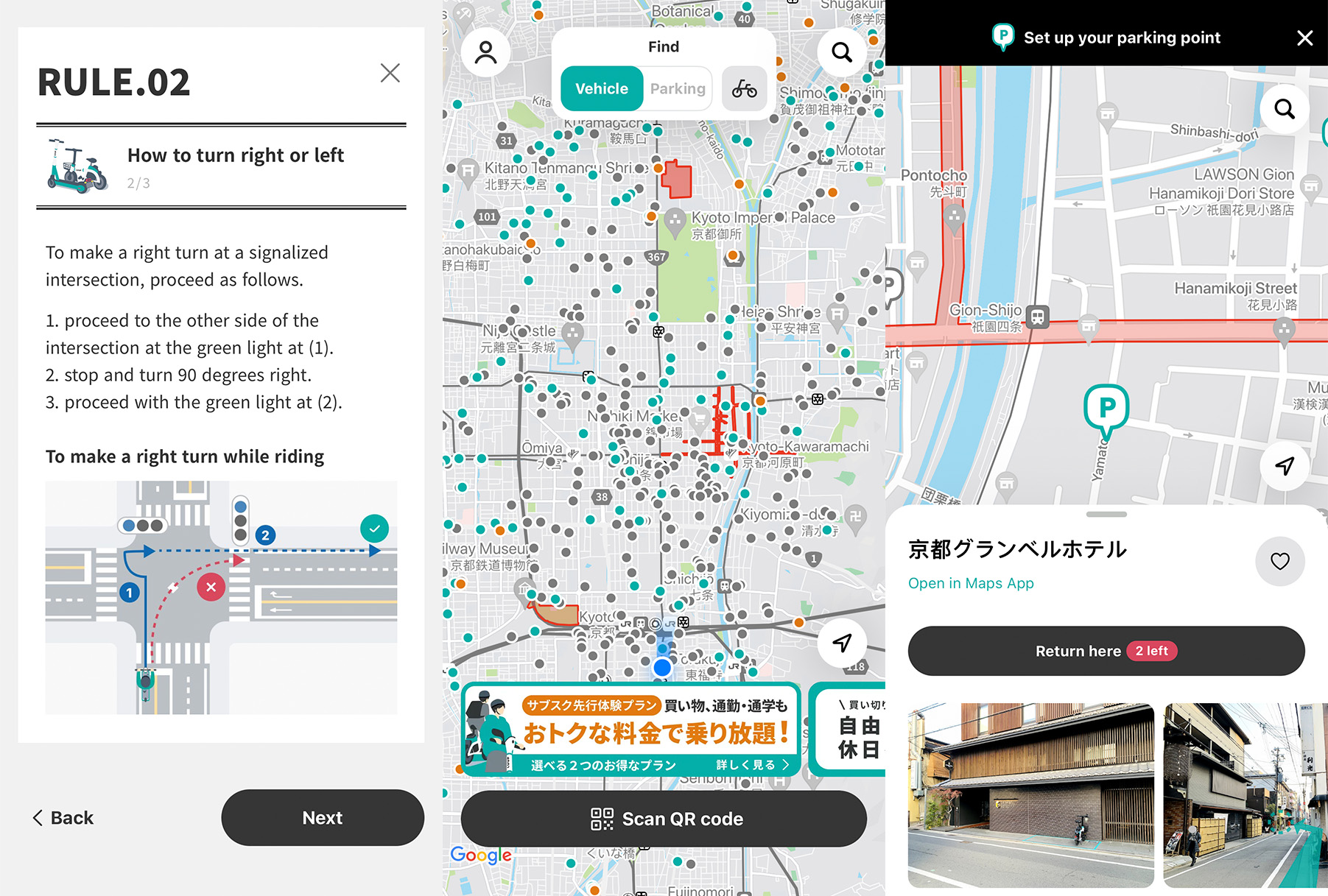

Opening up the Luup app, you first have to study the rules and pass a test to demonstrate you will be a safe road user, which honestly probably should be a thing on all bike and scooter share schemes. Crucially, one rule, of how you’re supposed to turn right, is clearly explained and is a rule of the road I wouldn’t have otherwise learned. [This technique is called the Box Turn – Ed.]

Having passed the test, in return for which I receive a free 30-minute ride, the map of available bikes populates like my phone has caught iPox.

After selecting a bike you then have to choose where you’re going to eventually park, which while a sort of restrictive thought process in contrast to the innate freedom of riding a bike, also makes sense for the public good. Helpfully, it also shows you a photo of exactly where the parking spot is, so you don’t have to rely on your phone’s sometimes-iffy and inexact GPS.

While the style of the Luup is more of a collapsible bike with those necessary yet annoying small wheels, it’s definitely the most fun bike so far, with a tight turning circle adding both a zip and the right amount of trepidation that it feels more like a toy than a bicycle.

A pal from back home has joined me in Osaka for a couple of weeks and elected for a Luup scooter as we made our way north to the city’s river bank for dinner. Initially, I was jealous of both his indicators and clown-car horn instead of my bike’s traditional bell. Yet, when we hit a slight downhill or the beginnings of an amber light, I could get out of my saddle and sprint over the limited 20 kmh of electric power that both of our machines were supposedly limited to. You’d take an extra 5 kmh over an infinite number of beeps and indicator flashes any day.

We arrived at our parking zone after 28 minutes of riding, leaving me two minutes spare to get the bike locked up before we tipped over our free ride allowance and had to pay for the privilege of a very fun half an hour. My back wheel was refusing to lock and the seconds were ticking by; after half a dozen annoyed jams which failed to close the lock, I realised I was trying to push the lock through one of the covered thick, plastic spokes. Human error strikes once again, the secretly already-sentient machines send facepalm emojis to each other as they look down from “the cloud.” With mere seconds to spare I finally got it closed and nervously checked the app – ¥0. Hurrah! Thanks Luup!

Tokyo drifting

Joyously, Luup also operated in Tokyo, the satisfying clunk as the lock flicked back a welcome cleanser to the utter madness of Japan’s capital and the 40 million inhabitants who live in its metropolitan area.

Outside of my capsule hotel, fresh from washing myself in the communal baths where I sat bollock-to-bollock on upturned buckets showering alongside the temporary inhabitants of one of the world’s great metropolises, there were at least five different Luup bikes available within a minute-walk of the chaotic Shinjuku ward.

Maybe it was just the reality of coming to the end of five weeks away from home, but Tokyo is draining. Finding properly fresh food sometimes seems like searching for a needle in a haystack when many in the city appear to subsist almost entirely off meals that are microwaved for you in-store at a Family Mart or 7-Eleven. Meanwhile, the pavements are packed with heads buried in phones not looking where they are going, watching videos or texting, swerving this way and that as if there is all the space in the world (there is not).

Everything is claustrophobic, the buildings pile up on one another, and below ground the subterranean walkways between train stations and platforms are also rammed. Shinjuku station hosts 3.5 million passengers each day, the busiest station in the world. Queues form at pedestrian crossings and good luck finding a seat at a café.

A simple bike ride is often the antidote to any sort of madness. Even in Tokyo.

It turns out the reason we’ve all been waiting on foot at traffic lights for so long is because you barely ever get caught at one while on the road. Like a water slide surfaced with tarmac, you glide through districts like it’s a lazy river or tranquil Mario Kart circuit without the bananas and red shells. In fact, people dressed up as Mario Kart characters and riding in go-karts pass me at one stage as part of an organised tour.

Drivers here are, however, definitely less respectful here than anywhere else so far on my trip, which I guess makes sense. I watch on as one cyclist indicates to try and move lane and the car coming up fast behind simply does not care, refusing to give way.

Heading north from Shibuya to Shinjuku, the metro ride would have taken 26 minutes, yet I make the journey in 23. Victory. Part of Tokyo’s allure is that to outsiders not much of it makes sense, but it’s comforting that the one constant, wherever you are, is that cycling still makes sense.

Like last year in America, the fact you don’t need to bring your own bike with you across thousands of miles in order to go for a ride is no small miracle.

Wherever you go there is the comforting familiarity of a bike ride waiting there for you, that not only allows you the freedom to explore but also centres you in these new worlds. The pain of downloading apps on super slow wifi and figuring out a multitude of slightly different share scheme systems is a low price for the simple and pure pleasure of riding a bicycle. As long as you can raise the saddle height.

Did we do a good job with this story?