Back in 2019, a group of Australian civil engineering and psychology researchers arrived at a rather stunning finding: around half of the non-cyclists they surveyed saw cyclists as less than human. The non-cyclists didn’t just dislike cyclists or find them annoying on the road – they saw cyclists as less-than-fully human, less-than-fully evolved.

At face value, it was a jarring claim. Surely even the most aggressively anti-cycling motorist wouldn’t argue that people on bikes literally aren’t part of the same species? Surely this was ‘dehumanisation’ in a more abstract sense, a denial of the “characteristics that are uniquely human and those that constitute human nature”.

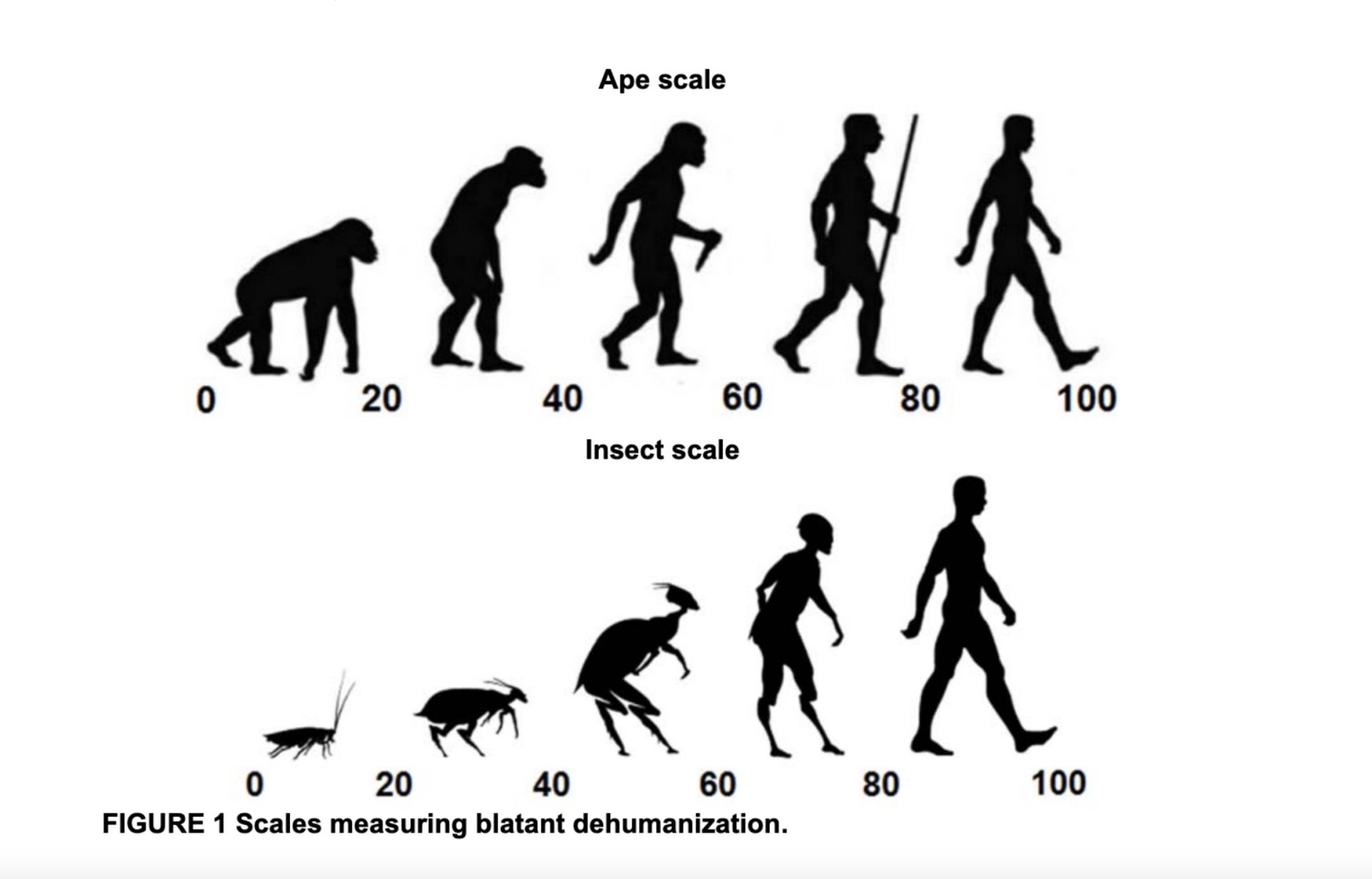

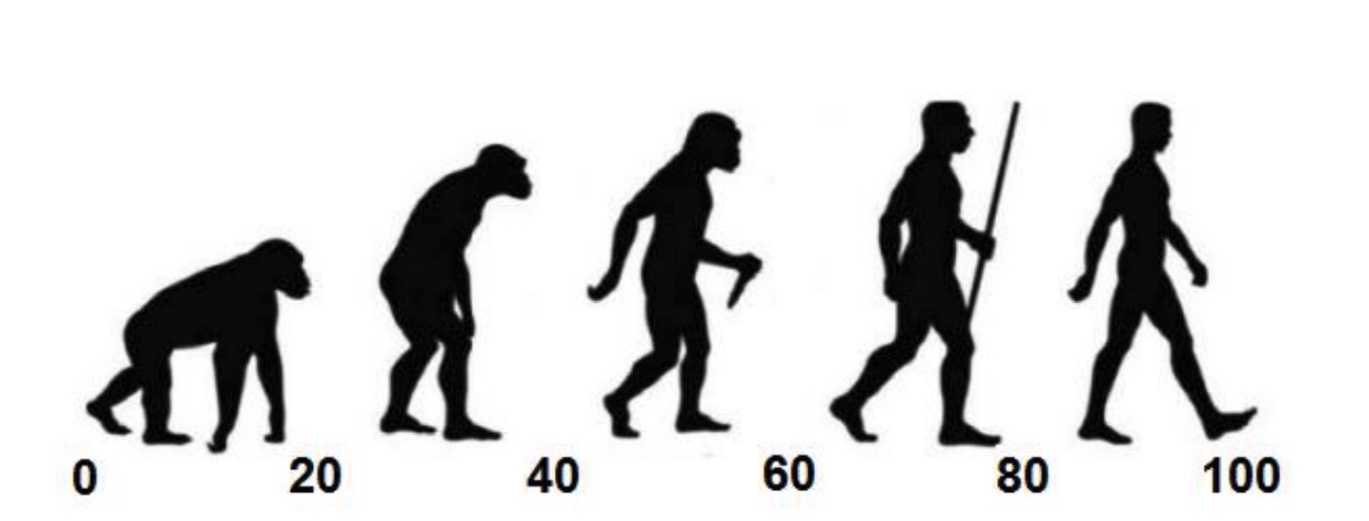

And yet, when presented with the following two charts, and asked to show “how evolved you consider the average cyclist to be”, 55% of non-cyclists in that 2019 study marked a point somewhere left of fully human.

Dehumanisation research tends to be more focused on racial, ethnic, religious, or sexual minorities, but that 2019 study showed that some parallels could be drawn with cyclists. A 2023 study, building off that 2019 paper, reinforced that view: cyclists in photographs were labelled as less human if the rider was wearing a helmet, high-visibility vest, or Lycra, compared to riders wearing just a T-shirt.

These dehumanising views alone are troubling enough, but one of the most crucial findings from this area of research is that these attitudes aren’t actually harmless. That 2019 research, headed up by associate professor Alexa Delbosc of Melbourne’s Monash University, found that these dehumanising beliefs were “associated with self-reported aggression such as throwing objects at cyclists or using a car to deliberately block a cyclist.”

Five years after their initial study, Delbosc and her team have now concluded another piece of work that pushes the discussion forward. This time around they’ve looked at how to turn the tide of dehumanisation; how to ‘rehumanise’ cyclists for those who see people on bikes as less than human.

In the introduction to their latest paper, Delbosc and colleagues share a grand aim: “If we can put a human face to cyclists, we may improve attitudes, increase support for cycling infrastructure, increase willingness to try cycling and reduce aggression directed at on-road cyclists.

“It may increase community willingness to support the investment in safe cycling infrastructure, reducing the likelihood of conflict in the first place. This could result in a reduction in cyclist road trauma or an increase in public acceptance of cyclists as legitimate road users.”

In working towards that lofty goal, Delbosc and co. narrowed in on public education campaigns about sharing the road with cyclists, and considered whether such campaigns can help to make cyclists seem more human.

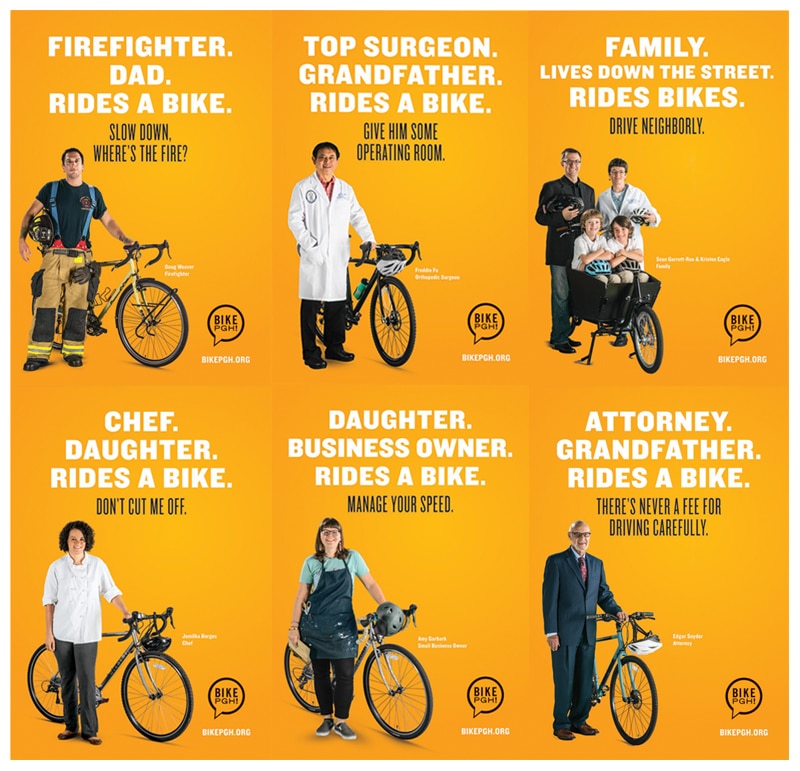

You might have seen some of the campaigns that inspired this work – campaigns that put the humanity of cyclists front and centre. In these films and images, the people on bikes are, first and foremost, family members, members of the community, everyday people. The fact they ride a bike is secondary to who they are.

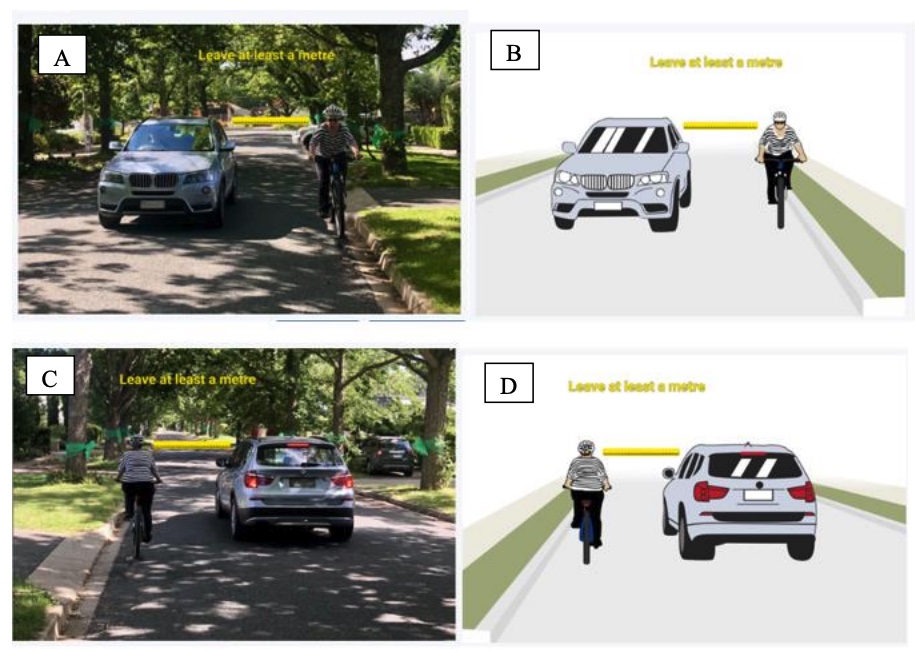

The posters that Delbosc and co. created for their latest study were rather more simple in design, and focused on encouraging motorists to give cyclists the legally mandated one metre of space when overtaking. Four versions of the poster were created:

- A photographic version showing the rider front-on

- A photographic version showing the rider from behind

- A graphical version showing the rider front-on

- A graphical version showing the rider from behind.

In an email to Escape, Delbosc admitted these are a “very simple” designs when compared to some of the existing, real-world campaigns, but with good reason.

“If you go too far you don’t know what it is people are reacting to,” she said. “For example, the images below I use in presentations, but if we showed those two different types of campaigns in a study, how do we know what’s causing the effect? Is it the photographs? The clothing? The detail? The colours?”

With their posters completed, Delbosc and co. began surveying a bunch of cyclists and non-cyclists in the Australian Capital Territory. After being shown the posters, the participants were asked to comment on how clear and memorable the message was, and how likely the posters were to convince them to follow the law.

They were then presented with eight statements from the long-used Attitudes to Cyclists Scale, and asked how true they felt each of those statements were:

- It is very frustrating sharing the road with riders like this

- Riders like this should not be able to ride on main roads without a cycle lane in peak hour

- Many riders like this take no notice of the road rules

- It is safer for riders like this to keep to the left of the lane

- Drivers are not trained to look out for riders like this

- Drivers need to be educated to give riders like this a fair go on the road

- If riders like this want a fair go on the road they should pay registration and road taxes

- Drivers should change lanes when overtaking riders like this rather than veering around them.

Later in the survey, the participants were asked about how human they see cyclists as. More specifically, they were asked how much they agreed with the following statements, from “not at all” to “extremely so”:

- I feel like cyclists are open minded, like they can think clearly about things.

- I feel like cyclists are emotional, like they are responsive and warm.

- I feel like cyclists are superficial like they have no depth.

- I feel like cyclists are mechanical and cold, like a robot.

- I feel like cyclists are refined and cultured.

- I feel like cyclists are rational and logical, like they are intelligent.

- I feel like cyclists lack self-restraint, like an animal.

- I feel like cyclists are unsophisticated.

And finally, Delbosc and co. presented participants with the ape version of the evolution chart they’d used back in 2019, asking participants to “indicate by marking on the line below how evolved you consider the average cyclist to be.”

In total, 267 people completed the survey. With all the responses collated and processed, Delbosc and her team could start drawing some conclusions.

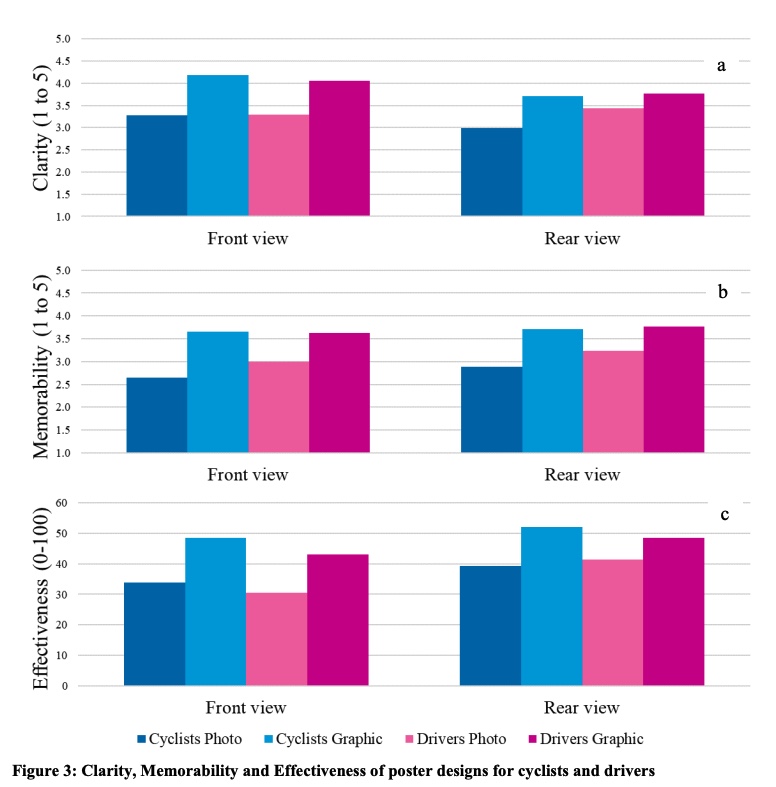

On the subject of poster design, participants found the graphical posters to be clearer, more memorable, and more effective than the posters that used actual photos. Both cyclists and non-cyclists had the same feeling.

When it came to participants’ attitudes towards cyclists, the findings weren’t terribly surprising. Cyclists exhibited more positive attitudes towards cyclists than did non-cyclists. Interestingly though, “drivers reported more positive attitudes to the cyclist shown from the front than from the rear”, while the orientation of the rider made no difference to cyclists.

The findings of the dehumanisation aspect of the study were a little troubling. “Cyclists rated the cyclist shown in the posters as more human than did the driver participants”, wrote Delbosc and co., noting that, on average, cyclists rated the rider as 91.6% human, and the average non-cyclists rated them as 82.9% human. More troubling: over half of all respondents – cyclists included – rated the bike riders in the posters as less than 100% human.

That’s a curious finding. Why would cyclists view other cyclists as less than 100% human? Delbosc explains that this isn’t entirely unexpected.

“You get similar responses when people rate their own social group in other settings as well (e.g. white people rating a range of ethnicities don’t all rate other white people as 100% human),” she said. “Some people might look at the question and think, ‘Well, there’s a little bit of ape in all of us, some people are jerks, I can’t honestly say everyone is 100% evolved’.

“For cyclists, I do know of people who love riding, but have had bad experiences from other bike riders. Perhaps that influences their judgement. More important in this kind of research is to look at the ratings either compared to other groups, or coming from different groups. (e.g. bike riders see other bike riders as more human than motorists, on average.)”

To drivers, the rider in the photographic posters was rated as more human than the person in the graphical posters. Which is perhaps not all that surprising – it’s easier to see someone in a photograph as human than it is when viewing a graphical representation of a person. Interestingly, while drivers had more positive attitudes towards riders viewed from the front, that rider was not seen as more human than the rider seen from the rear.

As Delbosc and co. explained: “While past research in other domains has shown that faces are humanising, we could speculate that the current findings reflect that drivers see riders from the back before passing, and so the rearview depiction is more relevant to the message being portrayed in the poster.”

So what do the researchers make of all this? What can be learned from the 267 responses they received? Well when it comes to designing cyclist safety campaigns, photos seem to be more effective at humanising riders than graphics. But it really depends on what you’re trying to achieve.

“If you want to change ‘hearts and minds’ about cyclists, use photos,” Delbosc told Escape via email. “If you want to portray a very clear, simple message, consider using graphics, but nevertheless, consider how you use those graphics.”

Delbosc admits that the posters she and her team used in this study weren’t perfect.

“The photos had to be taken during COVID lockdowns, from another city, asking someone to go out and take them for us!” she said.

Would the results have been different had the photos been better? If the rider wasn’t so bathed in shadow, particularly in the front-on view, would that have improved drivers’ attitudes towards cyclists, or their thoughts about the humanity of the rider?

And what would they have found had they tested one of the existing road safety campaigns that uses a “humanity-first” approach, like the one used in Pittsburgh? Is that campaign as effective at humanising cyclists as it feels like it should be?

As Delbosc noted above, that’s a much trickier thing to test than what she and her team investigated, but if it could be done, the answers would surely be fascinating. In general, though, more research is probably required to better understand the ways we can re-humanise cyclists.

At the very end of their latest paper, after wrapping up their findings, Delbosc and co. conclude with something of a tangential suggestion. They reiterate that people who ride bikes have more positive attitudes towards cyclists and see them as more human than non-cyclists. Again, that’s not in the least bit surprising, but it does, in the researchers’ eyes, provide an opportunity:

“If we can get more people onto a bicycle, we may set off a virtuous cycle that erodes dehumanising beliefs and increases support for safe cycling infrastructure.”

Sounds great. Getting more people on bikes would deliver all sorts of benefits. But even that is harder than you might think, particularly if we’re talking about riding on the road. And getting enough people riding on the road to start eroding dehumanising beliefs and increase support for safe cycling infrastructure? That’s going to take some time.

Did we do a good job with this story?