How much does it actually cost to manufacture a premium carbon road frame? How does US$400 sound? It probably sounds both surprising, considering current retail pricing, but also somehow expected, given the figures bandied about on internet forums. But that figure is only somewhat accurate; it’s more or less what Rob Gitelis, CEO of Factor Bikes, told us it costs in raw materials to make an Ostro VAM, but materials costs are just one tiny piece in an enormous bike pricing jigsaw.

We took that jigsaw puzzle and sat down with Gitelis with one simple question we never truly thought we’d get an answer to: How much does it cost to make a modern premium carbon bike? Manufacturing costs are a closely guarded secret regardless of industry type. But we, the riders, often feel we are being priced out of the sport we love. While we probably can’t change the pricing, it sure would be nice to understand why it’s only ever going in one direction: Up!

When I first pitched this article months ago in an Escape Collective edit call, everyone agreed it would make for fascinating insight. We also agreed it might be practically impossible. Trying to find a source with all the information we would require, not to mention the clearance to divulge it, was a tall order. “What are the total manufacturing costs for your flagship frame in dollars, please?” is not a question any company was likely to answer, nor would employees risk their jobs to tell us.

We needed an owner or CEO to not only see the value in effectively opening up their books but also have the courage to justify these numbers on the record. Very few of those people exist. One of them is Rob Gitelis of Factor. Rob owns Factor, and Factor, in owning its own factory, knows every piece of the bike price puzzle.

To be clear, we didn’t just want a dollar figure for the raw materials going into the mould; we wanted to know how much those moulds cost, staffing and payroll, facility costs, shipping, insurance, R&D, the impact wind tunnel time and CFD are having on retail pricing, and, of course, sponsorship and marketing costs. We wanted to know distributor and retail percentages, warranty costs, and everything down to the chain going on the bike. Only then could one determine if modern bikes are just pricey or outrageously expensive.

Caveats apply

Of course, getting this information from Gitelis means it is only representative of one manufacturer and not reflective of every brand or bike offering. Gitelis tells us Factor is a “10,000 bike per annum company,” which means there are plenty of manufacturers producing many more bikes, but there will undoubtedly be those producing less.

Furthermore, relying on one source means such an article could be seen as some justification exercise for the high prices charged by one of the most premium offerings on the market. But all that considered, we were also aware we were unlikely to find another current or former industry insider with the knowledge and willingness to share it.

We would still love to offer details across a range of price points, and that was the initial plan, so if you have those insights and are willing to share, please contact us in confidence.

It is also important to note that Gitelis has a business to run, and Factor has every right to make a profit. As do the distributors, and all the bike shops of the world. As such, if you are hoping to account for every penny of your purchase price, you won’t find that in this article. Delving into the costs and margins for each of those parties is past the scope of this article, but remember throughout, each party needs to cover their costs and turn a profit, and retaining a slice of a pie cut three ways means a bump from purchase to selling price for each.

Spoiler alert: While this article provides many of those figures, the structure of any manufacturing business defies neat attempts to fit costs like labour into per-product cost assessments. If you are sitting, calculator in hand, hoping to work out bike production costs down to the penny, you won’t find an exact answer. Some of the costs incurred by each business along each step of the way are simply company-wide, and attributing a percentage to each frame or bike sold is almost impossible. Each frame and bike will hopefully “cover its own costs” but equally, each must contribute to the overall operational costs of an entire business. And, since the value proposition is entirely subjective, you must determine that for yourself.

Nevertheless, if you want to get a greater understanding, unrivaled insight even, for how said “few hundred dollar frame” becomes a $10,000, $15,000, or even $20,000 bike, you’ve come to the right place. For purposes of a consistent comparison, all figures here are in US dollars, in cost per frameset per year. Why cost per frameset and not bike? Because parts kit costs vary considerably.

Rob agreed to record our interview for a podcast episode to accompany this article. That podcast is available below (or search Escape Collective on your favourite podcast app).

Do also consider listening to the Geek Warning podcast special episode accompanying this article. In the episode, Gitelis speaks openly providing an insight deep into the world of premium bicycle manufacturing and speaks at length on Factor specific topics such as the costs broken down in this article. More broadly, Gitelis talks us through some of the inner workings of the manufacturing facilities brands employ, staffing models, and his fears a repeat of the COVID boom and bust is just around the corner.

Finally, this is not paid or sponsored content. Escape Collective exists for and thanks to our members, whose memberships are our sole source of funding. Factor nor Rob Gitelis contribute any advertising spend or revenue of any sort to Escape Collective and aside from verifying the information used was accurate and in context, Factor had no editorial oversight of this article. To support work like this, consider becoming an Escape Collective member.

The role of inflation in rising bike prices

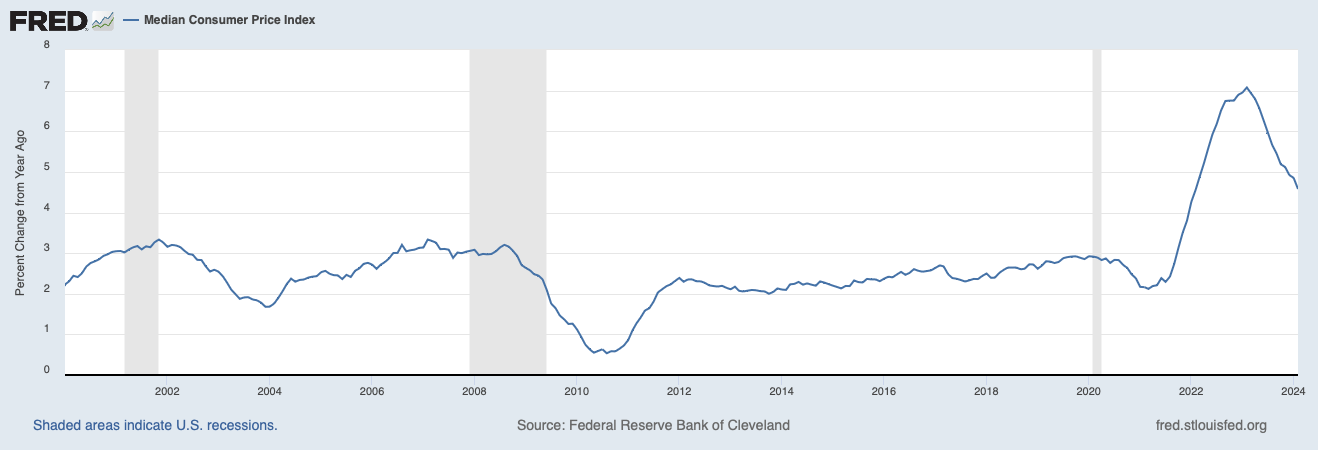

Answering what a bike costs is one thing; determining if that is value for money or expensive is entirely different. Many look to inflation as both a rationale for increasing bike prices or, on the opposite end of the scale, evidence brands are overcharging. And so to answer that question we must first establish if bikes are more expensive than they used to be.

Gitelis argues that bikes today might not be that much more expensive than in previous decades. He points to inflation and claims when we consider prices through this lens, the increase from a $3,000 premium bike of 20 years ago to the $10,000 bike today is “not all that outrageous compared with every other product on the market.”

Premium bikes like Trek’s 2004 Madone 5.9 (yep, the one with the shark-fin seat tube) had recommended retail prices of around $5,000 in 2004 dollars. Specialized’s S-Works Tarmac of the same year was $4,880. While inflation certainly plays a part, if we plug that $5,000 actual RRP for into the official Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation calculator, we get a projected cost of $8,279.78 at the end of February 2024.

That $8,279.78 is significantly lower than the $12,750 the same Madone model with Dura-Ace is priced at today, while the Dura-Ace Di2-equipped Tarmac SL8 goes for a whopping $14,000. That said, Gitelis makes a valid point in highlighting that manufacturers are not “selling the same bike we did 20 years ago.” Those flagship 2004 bikes each had an 18-speed cable-actuated drivetrain, rim brakes, metal bar and stem and low-profile aluminum wheels, with very little thought given to aerodynamics. Today’s aerodynamically-optimized carbon frame shapes and deep-section wheels, wireless electronic drivetrains, and hydraulic disc brakes are far more complex and costly; merely tracking inflation is not comparing apples with apples.

Finally, it’s worth noting that while the pricing at the absolute flagship end of the range has exploded, one or two steps down provides much better value, as well as pricing that is more in line with historical inflation trends. Specialized’s Tarmac SL8 line drops from $14,000 for the S-Works version to $8,500 for the Pro Ultegra Di2 model. Trek’s Ultegra Di2-equipped Madone SLR 7 is $9,100, and Factor’s Ostro VAM with Ultegra is $9,200. That’s a modest increase over inflation-adjusted 2004 pricing. What’s more, that money today buys a bike that is far nicer than those of 20 years ago: it’s lighter, with better wheel and frame aerodynamics, superior component and ride quality, and even perks like power meters.

Owning the factory vs. third party

While providing a fascinating insight, it must be said again that Factor is different to most brands in that it owns and runs its own manufacturing facility. “Most brands work with third-party manufacturers” to produce their frames, forks, handlebars, etc. Gitelis explains. Giant is another running its own factory but, according to Gitelis, there are around five or six top-level facilities producing bikes for many of the top brands plus a second tier of factories that manufacture frames for other brands.

These third-party manufacturers provide what’s known as a FOB (Free on Board) price for manufacturing a frame and fork, this means the manufacturers will produce and deliver the frames to the boat yard for shipping at which point the brand then takes over. The materials, overhead, and factory labour costs combine to dictate the FOB price. Whether premium or more mid-range, the labour cost to make a carbon frame is “nearly identical,” Gitelis tells us. It’s the material costs that will differ, while overhead is extrapolated from the other two. In his experience, Gitelis estimates these three cost centres each account for approximately a third of the FOB price.

Factor owns its own manufacturing facility, buys its products from its own factories, onsells them to its distributor network, who onsell said product to retailers, who eventually sell it to the consumer.

Raw materials – $365

So what are those material costs? As Gitelis quickly explains, that few hundred dollar figure many have heard isn’t all that far away; in fact, it is accurate for some entry or mid-range frames.

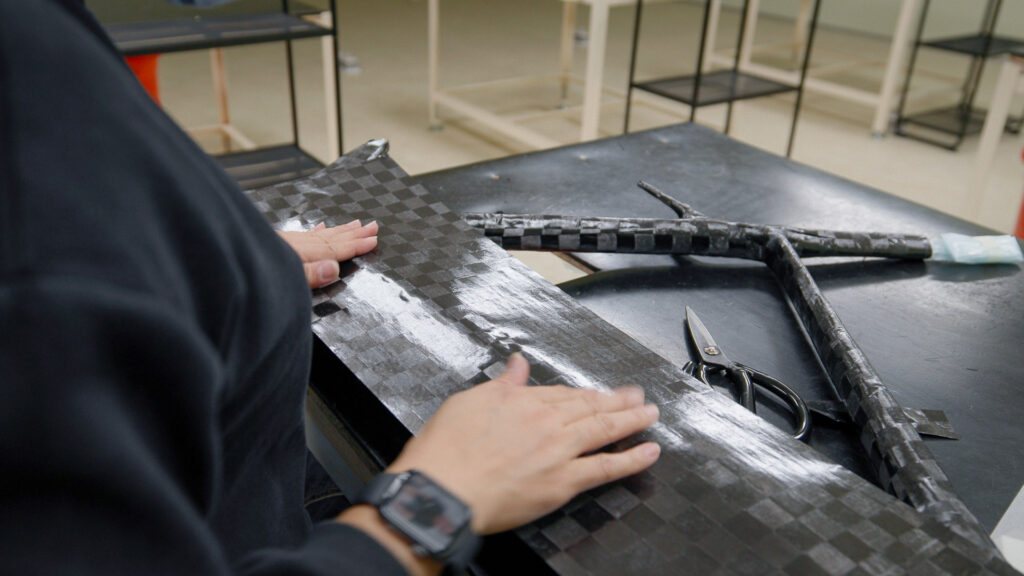

As for a Factor Ostro VAM, Gitelis tells us the carbon fibre material cost is around $330, with the EPS Styrofoam preform adding another $35, out of the mould. That’s $365 of raw materials going into the mould for each frame the factory produces.

The carbon fibre used has also changed considerably over the past few decades. Initially, brands relied on workhorse medium-modulus fibers like Toray’s T700 and 800 carbon in frame production, using very few, if any “exotic materials.”

As Gitelis explains, the Cervelo RCA changed all that, proving it was possible to make a considerably lighter but still reliable carbon frame. That’s when using what Gitelis describes as exotic materials – such as boron fibres and pitch-based carbon (as opposed to the more widely used PAN fibre) – became a requirement.

Some bikes do still feature T700 and 800 carbon, helping to make them more accessible, but Gitelis claims a modern premium, lightweight, and strong frame does require the use of these more exotic materials.

Moulds – $100,000-150,000 total per size run

Carbon manufacturing processes do vary in the industry, but laying up carbon plies in clamshell molds for curing is a common approach. Those moulds are specific to each model and size, so each new bike requires cutting a new mould – each half of the clamshell cut from a solid block of aluminum or steel – for each size in the range, and they are not cheap. According to Gitelis, introducing a new frame design can cost as much as $130,000 to create the six or seven moulds they need for a full size run. Add to that $6,000 per fork mould and suddenly a brand is looking at close to $150,000 just to create one size run of moulds. Bear in mind that many brands need more than one size run to meet production goals.

It’s here where things get complicated in terms of justifying these per-bike costs for both the manufacturer and the brand, because the fraction of those mould costs borne by each individual bike necessarily depends on the volume of frames produced. A brand’s most popular model may break even relatively quickly, and as such, the mould costs are covered and absorbed by many more frames, meaning that expense is amortized, or spread, over a far larger production run and the cost per frame drops. But for less-popular ranges – think time trial and track bikes – it becomes increasingly difficult for these frames to cover their own development and manufacturing costs.

Gitelis explains a third-party manufacturer may have to support a brand in producing its less-popular models because that support is far outweighed by the profit from the customer’s high-demand models. Gitelis suggests anything less than 1,000 frames per year with a lower-demand model may mean the manufacturer is only just breaking even on that bike.

For simplicity, let’s use that 1,000 frames per year as a benchmark, meaning that mould costs run to $100-$150 per frame for one mould, doubling with each subsequent set of moulds.

Research and Development (R&D) – $100

Being a manufacturer also means hiring the design and engineering staff to not only create the drawings for a new model but also take those drawings and turn them into a frame. These design and engineering investments are “significant costs,” especially, as Gitelis tells us, for smaller brands producing just a few models per year.

Gitelis suggests a 10,000-bikes-per-year company like Factor is perhaps spending $1,000,000 per year on R&D. It’s pretty simple math to work out that’s $100 added to each bike they produce. That said, he does explain if the R&D team develops more bikes, the cost is then spread amongst more products, effectively lowering the R&D cost per bike to the end consumer.

While R&D is a significant cost to the manufacturer, it is also somewhat a company-wide cost and, as such, difficult to attribute a cost-per-frame dollar figure, although we’ve done that here for simplicity’s sake. Think of the development work on a new time-trial bike: that development process could start with 3D models, and those models go into “three to five months” of CFD analysis and new iteration after new iteration. With the CFD complete, the engineers will “lock in the drawings” and CNC a prototype and take that to the wind tunnel. Gitelis tells us wind tunnel costs per new model could total $60,000-$100,000. From there it’s into the mould tooling and step one of actually producing a carbon fibre frame.

While, presumably, Factor can calculate a per-frame dollar cost for that process, brands will often tell us how the learnings from one development process fed into the next. Presumably, it’s impossible to calculate or attribute how the knowledge gained in the initial TT bike development process expedites (or complicates) the process of developing the next time trial bike or, more likely, the next aero road bike. That’s when the R&D cost per frame gets complicated.

Interestingly, Gitelis tells us CFD has become much more accessible as outsourcing opportunities bring the costs down from a million dollars of computing costs per annum to $600-$800 per month of cloud-based computing access.

Build Kits – $Varies

Of course, there’s more to a bike than just a carbon frame. Converting that frame into a bike requires wheels, handlebars, groupsets, etc., and they all cost money. While many of us, myself included, may long for the good old days of building frames with customer-spec build kits, those days are practically gone in the mass production sector. The modern way is sister brands or in-house component divisions of frame brands producing wheels, handlebars, seat posts, saddles, etc. In many cases, as with Factor, those become part of the frameset price (Factor’s frameset modules are sold with its proprietary Black Inc. cockpits and seatposts.)

In Factor’s case, each of those components is developed in-house, and as such, while not quite as high as a frame, the same material, moulding, R&D, CFD, and wind tunnel expenses all apply. All told, Gitelis claims Factor could be out $20,000 on developing a single rim profile into a finished wheel, and as much as double that for a wheelset with a variable rim profile front to rear.

Coincidentally or conveniently, these parts are often also proprietary and, as such, essential for any frame build. Gitelis happily admits components are “a place to earn a little more margin,” but is keen to point out that these proprietary components are largely an optimisation element, claiming it is becoming “too difficult to rely on a handlebar vendor to have a handlebar available that matches (in performance terms) your design.”

Interestingly, brands and manufacturers are seemingly paying trade prices on components, no doubt with a decent volume discount, just like a distributor for groupsets and other parts. Gitelis explains his philosophy is Factor should make a profit on the products it produces, while products it is buying in just to pass on should not provide a significant profit centre. Try telling that to the contractor who built our house and merely facilitated a kitchen upgrade.

Again, while we only have Gitelis’ insight to go on, this seems to make sense given that calculating a full build price for a bike using the trade prices for individual components from the various brands listed on various distributor B2B platforms Escape Collective was provided access to usually works out to be more expensive than the complete bike trade price.

Logistics – $120-400

Manufacturing a bike is only step one; those bikes need to get from the manufacturing facilities to the distributors and dealers around the world, and again, that all adds costs.

Brands and manufacturers typically transport bikes by sea – sometimes air, as was the only option for long periods during COVID-19 and the Suez Canal block – to regional distributors (brands operating a direct-to-consumer model ship directly to consumers). Sea freight is by far the most cost-effective way of transporting bikes, adding around a claimed $40-50 dollar per unit, compared to airfreight, where costs can rise to as much as $200 per unit.

There are also import costs. Gitelis estimates this is around 11% on a complete bike coming into Europe, but it’s the insurance figure of around $1,000 per container of bikes that is surprising, although perhaps it shouldn’t be. As Gitelis explains, “containers disappear; around 1/100 doesn’t make it to its destination,” either dropped overboard, stolen, or simply lost.

These costs are all incurred by the distributor and understandably need to be passed up the chain as the distributor sells to the retailer. Combined, these could add between $120-$400 per bike.

Sales network

Once again, Factor is a brand that owns its own manufacturing facility, buys its products from its factories, and sells them to its distributors. These distributors then sell said product to retailers, who eventually sell it to the consumer. Each step of that chain is a business required to and entitled to turn a profit; Gitelis tells us in the cycling industry, it is normal to expect a distributor to have a 30% margin, while that margin is more like 30-40% for dealers.

In speaking with dealers of premium bikes from other brands I’m told the dealer margin used to be closer to 40-50%. But comparing the claimed 30-40% to yet another brand on one B2B site Escape Collective was provided access to suggests an average dealer may expect a margin of around 26% on a $10,000 flagship model sold at the manufacturer’s recommended retail price (RRP or MSRP). “Sold at RRP” is critical here, as any retail discounting rapidly diminishes the dealer’s margin, although not the manufacturer’s or distributor’s.

Marketing/sponsorship – ~ $300

Chicken or egg? Do you sell more bikes sponsoring WorldTour teams and professionals or does selling more bikes allow you to sponsor more teams? For Factor, it was very much the former, having sponsored the WorldTour Ag2R la Mondiale squad before it even sold a bike. Almost a decade later, Gitelis tells us Factor is “almost at a place where its marketing budget makes sense.” Gitelis suggests a marketing spend somewhere around 10% of revenue is the sweet spot; any less the company can’t grow sufficiently, any more is unsustainable, Factor is still above that figure, but Gitelis explains that is because it is a racing brand at heart, and supporting the racing community is key.

That support could range from as much as $3,000,000-$5,000,000 per year for a men’s WorldTour team, which consists of both cash and equipment costs. Going back to that 10,000 bikes per year figure, if spread equally among all bikes, that could be as much as $300-$500 added to each bike. For most companies marketing expense is a company-wide cost that’s difficult to assign a per-bike value, but it works for Factor because of the unique nature of the company: they only make premium race bikes.

Asked if this added cost is a fair deal for the consumer, Gitelis is keen to point out that while a consumer is free to choose a bike from any brand they wish, he can justify Factor’s marketing commitments, claiming it learns a lot from racing, but also supports racing at various levels, with three teams in the Women’s Tour Down Under all on free Factors.

Summing up, Gitelis claims, “If we are not in the WorldTour, we can’t sell as many bikes as we do. If we don’t sell as many bikes … we can’t support other more charitable things we do.”

Gitelis points to social media marketing as a new and “very significant” expense that didn’t previously exist. It’s also an expense that Gitelis sees as “the downfall of other media” specifically print and online, because the budget that would previously have gone to advertising is now going to performance marketing through social media, Google, Facebook, Instagram etc. Factor has a “few people in the company dedicated to” this new marketing.

As for reviews, Gitelis tells us Factor budgets around $50,000 per year on the allocation and shipping of 10 review bikes to various “tier 1 and tier 2” media publications in the first year after the launch of a new model. Escape Collective is entirely member-funded, with no revenue or input from brands or manufacturers into our reviews or other content, but we know some publications require an ad spend from a manufacturer in order to have its tech team review a product. Asked if Factor is paying for reviews, Gitelis is clear Factor does not pay for reviews.

Bikes are expensive: To make, and also to buy.

Modern bikes cost a lot of money, whether they provide value for money is debatable but ultimately only answerable by each individual. For many, the unfortunate reality is that the current prices are excluding far too many people from the sport we love. Could we all enjoy more affordable new bikes if the market was bigger? That’s another chicken or egg question. What Gitelis’s insight here tells us is that there’s a lot more expense in a bike than simply the raw materials.

Each frameset from a brand like Factor has at least $1,500-$2,000 in direct associated costs by the time it gets to an owner’s hands, based on a 30% distributor and dealer margin each, but not including Factor’s own profit (or that, in Factor’s case, frames are sold as modules with bar/stems and seatposts).

That figure, of course, is well short of the $5,500 RRP for a frame module like the Ostro VAM. But the $3,500 gap is anything but pure profit. Our analysis accounts for most direct costs, but not all (the cost of the extra module parts like the bar/stem and seatpost is extra). It also doesn’t account for the associated indirect costs in running any company that we didn’t even delve into: For a brand like Factor that would include factory costs like labour, energy, and real estate; office staff salaries and benefits (outside of the R&D noted above), software, the various different insurances any company requires, quality control, office real estate or rent, warehousing, currency hedging, VAT bonds, brokerage, regulatory compliance, heck even the silly reflectors bikes sold in the US or UK must be supplied with. All together, those various costs add hundreds or even thousands more dollars per frame to the production expense.

Lower prices would certainly help improve access to the sport, and more volume is seemingly the most effective way to reduce the expense passed on to the consumer.

More volume is a nice idea, but it obviously requires more cyclists and specifically more cyclists buying new stuff. That said, the current three to four-year life cycles of most premium WorldTour bikes are not helping. Prolonging the life cycle of each model would enable manufacturers to extract more value and profit from every development process and extra bike sold.

Perhaps that’s one of the side effects of the fact we, the average rider, can buy the very same bike the pros are riding to WorldTour success. That pursuit of WorldTour success is always going to see teams driving manufacturers to produce newer, faster, lighter equipment. The more new stuff the pros get, the more new stuff we the consumers want. That has me thinking, I’m not sure if the chicken or egg came first, but completing the complex “how much does it cost to make a bike?” jigsaw puzzle feels very much like a wild goose chase.

Did we do a good job with this story?