Almost to their own surprise, Wilier has a new time trial bike. The Italian heritage brand already had two time trial bike offerings in the Turbine and the Turbine SLR, and so when they signed last fall on the dotted line to supply Groupama FDJ team bikes on a multi-year deal starting in 2024, a third was far from an immediate priority. That was about to change, though, and what ensued became a race against the development clock to design and build a new bike for the race against the clock.

The end result of that race against the clock is Wilier’s new Supersonica SLR, first raced by Stefan Küng, with whom we have an episode of the Performance Process podcast with Küng dropping later this week, at this week’s Tour de Suisse opening prologue. The new bike developed in rapid time has ditched the Kammtail and truncated tubes that have dominated cycling design for the past decade and sees the return of true NACA (National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics) profiles throughout, an integrated seat post, custom extensions for all and is the result of a claimed 50 hours of simulations, 30 hours testing in the wind tunnel, real-world testing in the velodrome and outdoors, CFD and wind tunnel-testing five leading competitors’ time trial frames, and countless late nights and weekend hours.

Oh, did we mention: The frame module is priced at a whopping €9,000, and a complete Shimano Dura-Ace build with Miche wheels, and custom time trial extensions costs an eye-watering €27,400!

Wilier gave Escape Collective exclusive access to follow the development of the new bike over the past four months to tell the story of how a TT bike is developed, why a UCI rule change meant the water bottle ended up costing €22,000, and all the testing that goes into ensuring the new bike is actually faster for Stefan Küng.

“Two is company”

Wilier was already supplying Astana and, with the addition of Groupama, became one of the few bike brands supplying multiple men’s WorldTour teams. That’s a huge commitment for any brand and a commitment with considerable pressure to deliver. But Astana and Groupama are very different WorldTour beasts. Only two years ago, Astana pushed Wilier to develop a lighter, almost climbing-specific time trial bike, the Turbine SLR. Groupama on the other hand, with a team of sports scientists and aerodynamicists demands something different … a more aerodynamic time trial bike. In fact, the entire partnership with Wilier to supply the team with bikes hung on it.

Groupama-FDJ, through its various guises, has plenty of time trialling pedigree over the past decade or more. The team has paid particular attention to team and individual time trial performance optimisation so it should come as little surprise that the team insisted on taking Wilier’s current TT offerings to the wind tunnel before committing to race the Italian brand’s bikes.

Wilier thought they had a deal … if those existing bikes tested as fast or faster than Groupama’s Lapierre TT bikes, the team would commit to Wilier. But they were wrong.

Although, according to Wilier, at least one of the existing bikes hit the marks in the wind tunnel tests, Groupama had other ideas. Shortly after signing the partner agreement, Groupama did what every high-performing team should do and started demanding more.

Groupama has Stefan Küng, one of the best time trial lists in the world, a former European champion who’s stood on just about every time trial podium going. And 2024 is a big year for the big Swiss engine. Not only are there the usual Tour de Suisse and Tour de France time trials to target, but Küng has an Olympic Games and home World Championships on the calendar. Wilier’s TT bikes may have passed that initial test, but the team and its star time triallist wanted more for such an important year.

More is less

What is more? Well, actually, they wanted less: a TT bike with 10% less drag, to be specific, and they wanted it in less time than most would even dream of developing a new bike. Wilier would have just four months to design, develop, and hit go on an entirely new frame.

That’s a timeline that Wilier’s head of design Marco Genovese described as “practically impossible” on a Geek Warning special episode out now deep diving into bicycle design and the new Wilier time trial bike. In the episode, Marco described how the initial concept for the bike comes tighter, building on his experience and modern tech, but also how that limited timeline meant there was no plan B. It was plan A, the bike we see today … or nothing.

Sure, there could be minor tweaks to the carbon layup and so on, as was the case, and we will cover in a bit, but once the moulds were cut and the prototype frame produced, Küng would either have the frame that we now know as the Supersonica or he would have the existing Wilier TT offerings. Which it would be would come down to the testing.

The proof is in the tunnel

The February day the initial carbon prototype landed at Wilier HQ, the anxiety was apparent. Both Genovese and Claudio Salomoni, Wilier’s Innovation Lab specialist, spoke to Escape of the pressures of such a short timeline, the late nights and weekends in the office just to get the initial design work completed. I’d imagined a design process beginning on a drawing board with a designer sketching out new concepts before analysing, testing, and effectively proving their work over a long, long period of optimising every tiny detail. But Genovese dispelled much of that, explaining there simply wasn’t time, and so a combination of his experience and modern tech took over with talk of parametric design, CFD, and incredibly complex (for me, at least) CAD drawings.

The upshot of all that work was a 3D print of the “Plan A” frame that Wilier took to Silverstone wind tunnel last December. I wasn’t present for that session, but as sources told me, that wind tunnel visit should have been make-or-break for the entire project. If it tested fast Wilier could proceed with confidence; if it didn’t, there wasn’t time to start again. I wasn’t present that day, but reading between the lines of Salomoni explanation of that test, it seems the results provided just enough confidence to press on with the Supersonica development. Wilier had purchased TT bikes from “leading competitors” for comparative testing and claimed the 3D-printed prototype of the new frame had seemingly outperformed all these, but the non-rideable prototype model began to vibrate and flex at the outer edges of the yaw sweep, meaning the test results at these yaw angles couldn’t be trusted. Wilier would have to press on in hope as much as in confidence that a carbon, structurally sound version of the new bike would prove fast across the entire yaw sweep.

Press on they did, and I next met up with the team in Belgium in the second week of March. This time Wilier had flown themselves and me to Belgium to meet up with Groupama-FDJ and Stefan Küng as they were in the middle of their spring classics campaign. The goal here was to road-test the new TT bike for the first time and get Küng’s own feedback.

The road test didn’t involve any timing or aero testing; that would come later. Instead, Küng would complete back-to-back segments first on the existing Turbine TT bike he had used since switching to Wilier at the start of the season and then on the new bike.

Again, there was no plan B, so if he didn’t like it … well, I never quite got an answer as to what would happen if Küng didn’t like the new bike. Would it mean scrapping the project, or would it mean delaying? It wasn’t clear.

In the end, Küng was generally happy with the speed of the bike, but reported flex in the seat tube and head tube. Thankfully, as Genovese explains in the Geek Warning podcast linked above, those were fixes that Wilier could address through new carbon layups in the already existing moulds.

As much as I appreciate the handling on the Factor Hanzo TT bike I ride, I did head to Belgium that week wondering if, for an aero bike, there was any value in all the effort and expense of bringing everyone and everything to Belgium. Surely, aero testing is where it’s at for the modern TT bike. But Küng’s feedback seems to highlight the value of any and all testing, including on open roads. The wind tunnel can’t evaluate handling or power transfer, but with TT courses evolving and becoming more technical (another topic Küng discusses on the Performance Process podcast), confidence-inspiring handling characteristics are critical in any bike.

The exact carbon layup matters little in the wind tunnel, though, and so while Genovese worked on a new carbon layup for the next prototype, Wilier also headed back to Silverstone in mid-March, knowing the carbon prototype Küng trialled in Belgium would provide more conclusive aero-testing data than the original 3D-printed frame could. Wilier tested both the bike sans rider (and without extensions) and with a 3D-scanned Stefan Küng mannequin. They did also get Küng himself into the tunnel later.

Still, though, if the development team were short on time to begin with, they had practically run out at this point. That wind tunnel testing might decide the Supersonica’s fate, but either way, it wasn’t going to be getting any updates or improvements this year. To a certain extent, Wilier, Küng, and Groupama-FDJ were committed to the Supersonica at this point, regardless of how it tested. There were follow-up wind tunnel, real world, and velodrome aero testing sessions with Küng, but these were all with a view to optimising his position rather than making any further updates to the frame.

I was trackside for one of those positioning sessions occurred in early April at the Tissot Velodrome, Grenchen, Switzerland, a session made possible thanks to the many mutually beneficial opportunities it presented for various stakeholders. Wilier could do some final testing with the new custom extensions, Groupama-FDJ and Küng would benefit from any chance to optimise his position, and the Swiss Cycling Federation – who facilitated the entire test session with track time, staff, and testing equipment – would ultimately benefit from helping one of its best medal hopes at both the Paris Olympics and home World Championships.

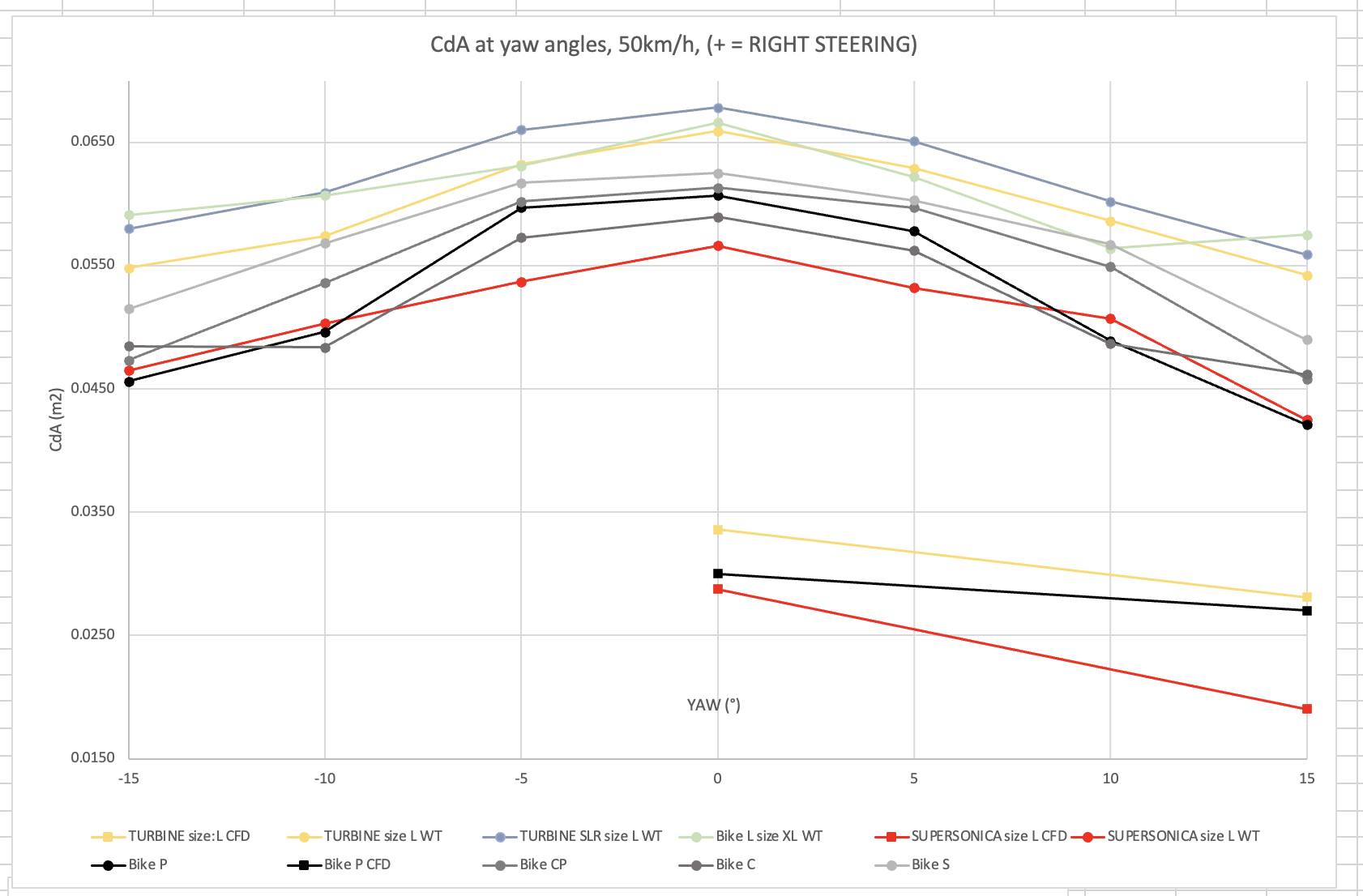

Given, as previously mentioned, we’ve seen the bike in use in this week’s Tour de Suisse, you’ve probably already figured it must have tested somewhat decently. It certainly looks fast, but is it actually fast? We have to rely on Wilier’s own results to answer that question, so the usual “manufacturer’s own testing caveats” apply, but the brand is claiming the new Supersonica represents an average 18.5% improvement over the brand’s existing Turbine SLR across an entire yaw sweep and 12.5% over the original, more aero-focused Turbine.

Of course, we all know aero testing can be manipulated to get certain results, but Groupama hadn’t just said, “Make the bike 10% faster.” They’d actually given Wilier a specific setup including wheels, groupset, and chainring size Wilier would have to use for the comparisons. The above results are from the initial bike testing without aero extensions. Adding the Küng-shaped mannequin (and aero extensions required to support the mannequin), the Supersonic saving drops to around 1.8% of total system drag, highlighting the fact the rider is by far and away the biggest drag contributor in the complete system. That said, a 1.8% saving is still a saving, and Wilier claims by its calculations Küng would have finished second in the Volta ao Algarve time trial this year had he been on the new bike compared to the third place he achieved on the existing bike.

Everything old is new again

So how and where did Wilier find these savings? The most striking thing about the new bike is undoubtedly the huge aero profiles and integrated seat post. Genovese had an idea to use NACA 0020 profiles, (00 meaning zero camber, and 20 describing the maximum thickness of the airfoil as a percent of the chord length, 20% in this example) rather than the Kammtail or so-called truncated profiles that have been popular in frame design over the past decade or more thanks to that profile’s balance of weight, stiffness, and aero properties.

But the Kammtail is a balance, or a trade-off if you will, offering a tube profile more aero than a round tube but not as fast as a traditional NACA profile. Many brands opted for Kammtail profiles as an ideal compromise; optimal NACA profiles weren’t always compliant with the UCI’s frame-design rules, in particular on tube aspect ratios. But in the years since Kammtails first came into vogue, the UCI has changed those rules. So Wilier decided the only way to achieve Groupama’s drag targets was to revert to traditional NACA profiles.

To be fair, this isn’t the first time Wilier has questioned the value of the Kammtail profile. It already introduced a slight rounding to the trailing edge on the Kammtail-profiled tubes used on its Filante SLR aero road bike. Wilier pointed to testing which indicated rounding the trailing edges of the Filante’s Kammtail tubes improved performance at higher yaw angles and in turbulent conditions in the real world.

NACA profiles disappeared for a decade ago for a reason: increased weight and, especially flex. To be compliant with UCI frame design rules, NACA profiles have to shrink in proportion, which makes them less stiff. In fact, even with the more relaxed UCI rules on tube shape and size, the flex Küng reported following the test in Belgium was likely due to the tube profiles used.

Wilier was able to first mitigate the flex issue by using a double-wall tubing construction inside the profiles and later by changing the fibre types used in certain locations following Küng’s feedback. The so-called double-wall structures is a new feature Wilier has started using made possible with modern construction methods and sits inside the tubes perpendicular to the flat surfaces of the aero profiles. They reduce flex by directly targeting the buckling effect such deep and narrow profiles can be prone to.

Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, the Supersonica features tall and prominent seat stays with a much higher interface to the seat tube than seen on other recent time trial frame designs. Genovese explained that high interface helped claw back some of the stiffness lost in opting for NACA-profiled integrated seat post, and their aero penalty was mitigated by once again opting for a true NACA profile. The seat stays are also positioned directly inline with the front fork in the hope they can effectively hide behind the fork blades, making for a smoother flow over the bike – although just how effective this is at anything other than a zero-degree yaw angle and in the real world is probably up for debate.

The new base bar also adopts a profile straight out of the NACA catalogue, but things get a little more custom when we move north onto the time trial extensions. Wilier brought new prototype extensions for Küng’s approval to each test. The final solution incorporates a 3D-printed main body from base bar all the way up to the hand grips. The hand grips are a separate and removable component offering the chance to change the exact length or shape should Küng want to make alterations in future. It’s a neat solution to incorporate some adjustability in a fully custom solution.

Wilier will also offer 3D-printed and carbon versions of these extensions for riders deciding to fork out some €27,400 on a Supersonica.

UCI meddling

As potent as Wilier claims the Naca 0020 profile is, it does present one problem: the water bottle. Groupama required that the frame offered some fluid-carrying capacity and, unlike in triathlon, the UCI rules mean a bottle is the only option. So, as any good designer would do, Genovese ditch the traditional round bidon and cage and set about designing a bottle that neatly integrated into the TT frame and – heck, who knows? – could maybe even offer an aero advantage. That is after all what most manufacturers are now doing with their newest TT frame designs.

Accurately aware of the UCI’s published regulations and the requirement to leave space to pass a credit card between bottle and frame, Genovese came up with a design that mostly and very neatly bridged the gap in the lower section of the frame’s inner triangle. That design was sent off to the UCI technology department on Christmas week for preliminary approval (full approval would come as part of the complete frame approval process after the first frames are manufactured). An email back advised the design was in keeping with the UCI regulations and preliminary approval was granted. Genovese ticked the bottle off his to-do-list and moved on to the rest of what must have felt like a never-ending list as the time remaining to complete the job kept counting down. But the UCI apparently had other ideas.

A little over a month after getting the initial OK on the bottle, Genovese sent the final frame design to the UCI for overall preliminary approval. That’s a necessary step as manufacturers need to be certain the UCI will approve a frame before committing the megabucks required to open moulds and begin manufacturing a new frame. At this point the UCI came back approving everything … except the bottle, which it now said was not permissible citing a regulation that was never published and that no one at Wilier had ever seen before.

Long story short, the UCI wanted an almost-meaningless alteration to the bottle cage, and Genovese spent a whole chunk more time making the alterations to the bottle to achieve effectively the same design but in a way that adhered to this new rule seemingly plucked from nowhere almost overnight. All told, Wilier ended up spending an estimated €22,000 on the bottle and cage development alone, or roughly the equivalent of a single bottle in some Monaco champagne bars.

Somewhat hilariously considering that price tag, Küng couldn’t even drink from the bottle attached to the bike during testing as it was 3D printed using nasty materials you really don’t want to be ingesting. That was just a test bottle, though, and the production bottles will be made by Elite specifically for Wilier, and any liquids contained within will be safe for consumption.

But it’s not all about aero; there are other features to the new frame, including a new patented built-in fork over-rotation limiter for the bayonet-style fork steerer and a removable front derailleur mount. That front derailleur mount is designed to accommodate and improve shifting on larger chainrings with a lower 56-tooth position and a higher 63-tooth position, although with Ineos now setting a new precedent using a Classified Powershift-equipped hub along with 66-tooth chainrings, perhaps those front derailleur mounts are already surplus to requirements.

Definitely surplus to requirements now is the previous-generation Turbine TT frame. The Supersonica now replaces that frame and sits alongside the Turbine SLR in Wilier’s TT offerings. Unfortunately for some of Groupama-FDJ, Wilier has only produced the new frames in Küng’s L/XL size so far, and those needing XS/S or M frames will probably have to wait until next year. In the meantime, Wilier, Groupama, and Küng himself will be hoping the new bike can give him an edge to convert so many podium finishes into gold and rainbows at the upcoming Olympics and Worlds to join the European Champion stars he achieved in 2020 and 2021.

Editors’ Note: Wilier covered travel costs for the reporter’s attendance at testing sessions. Escape Collective is member-supported and ad-free and has no commercial relationship with Wilier.

Did we do a good job with this story?