Whether it's innovative patents that never lead to an actual product or seemingly obvious products we wish they’d make, it sometimes feels like drivetrain manufacturers aren’t in touch with what riders actually desire.

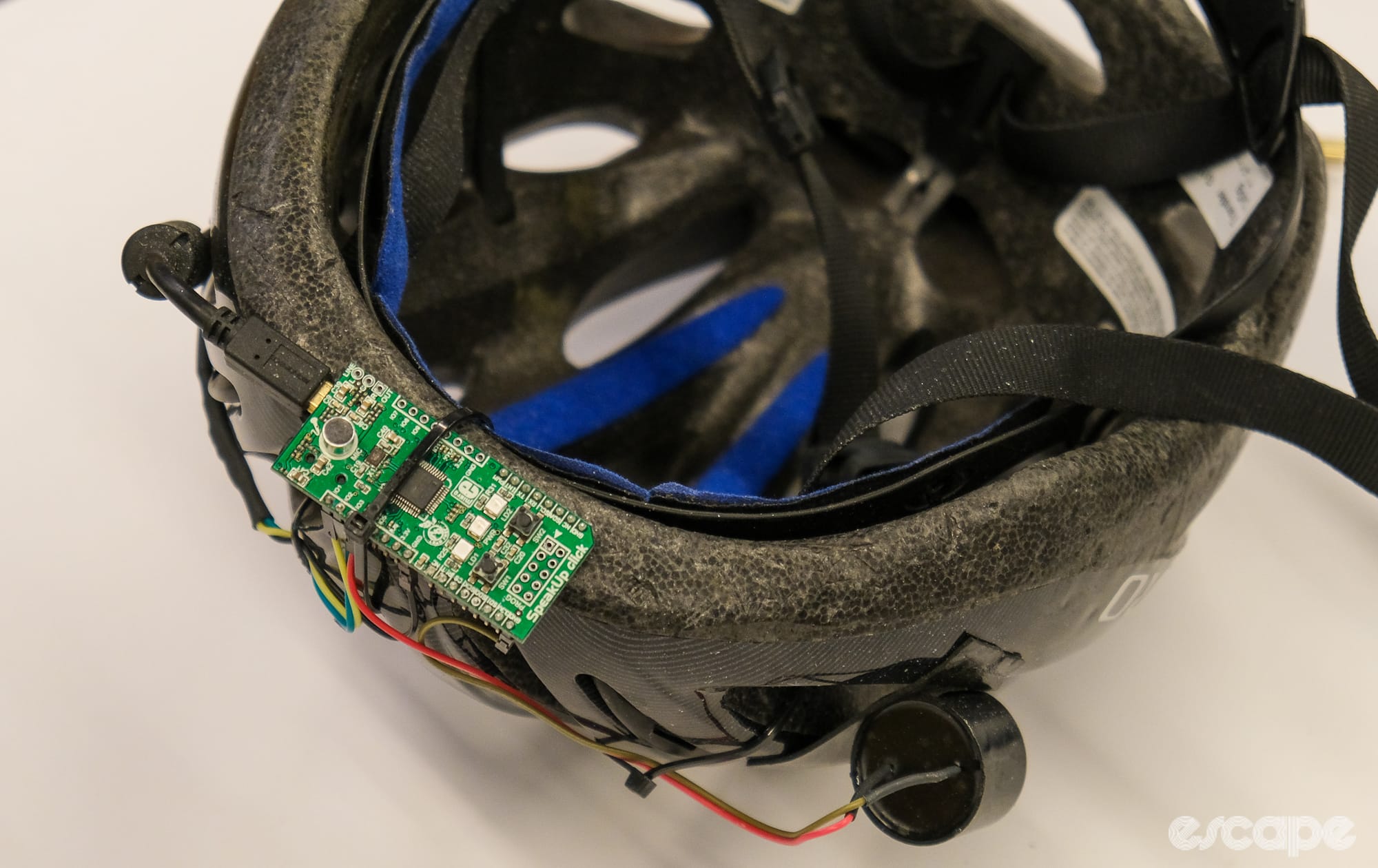

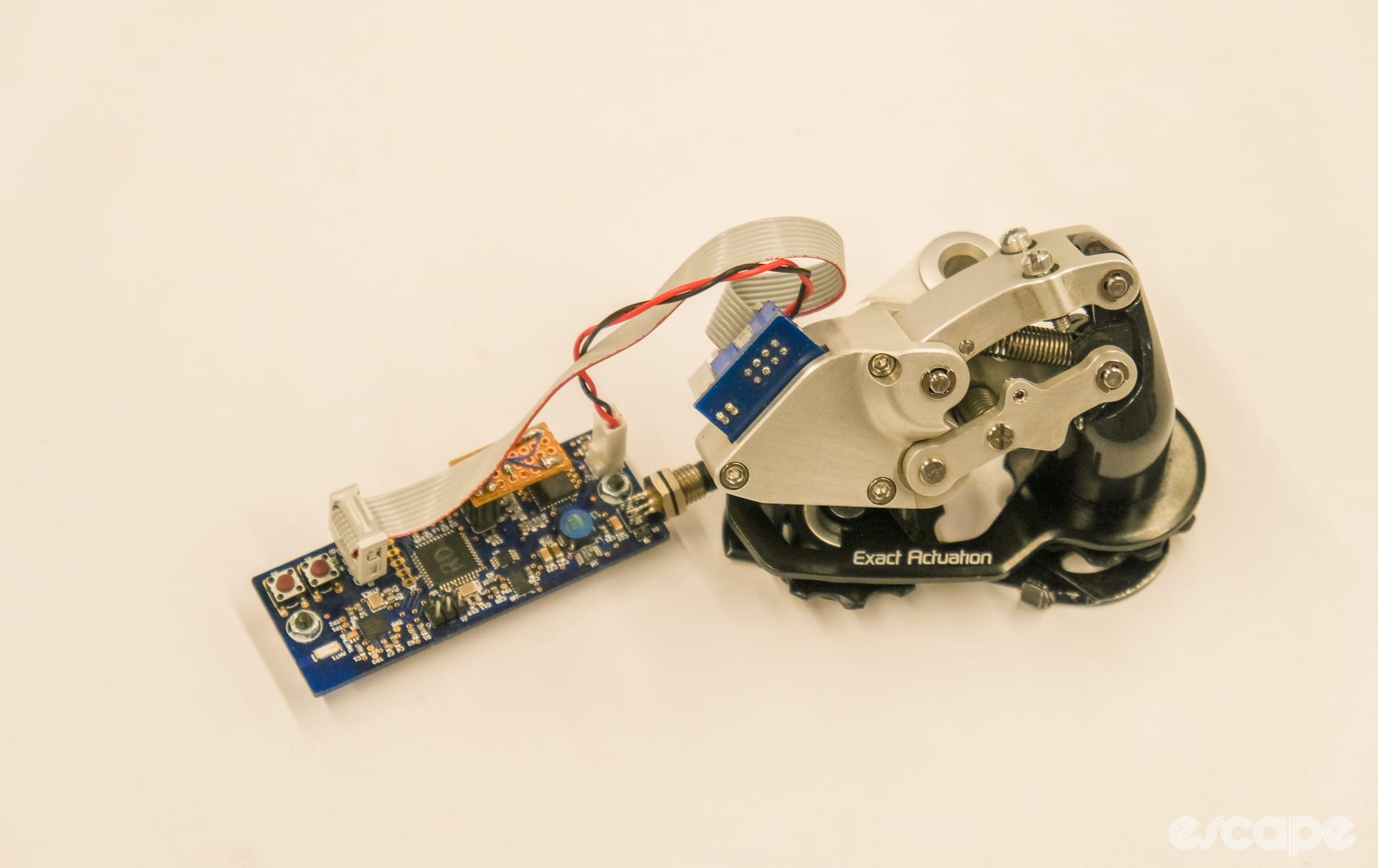

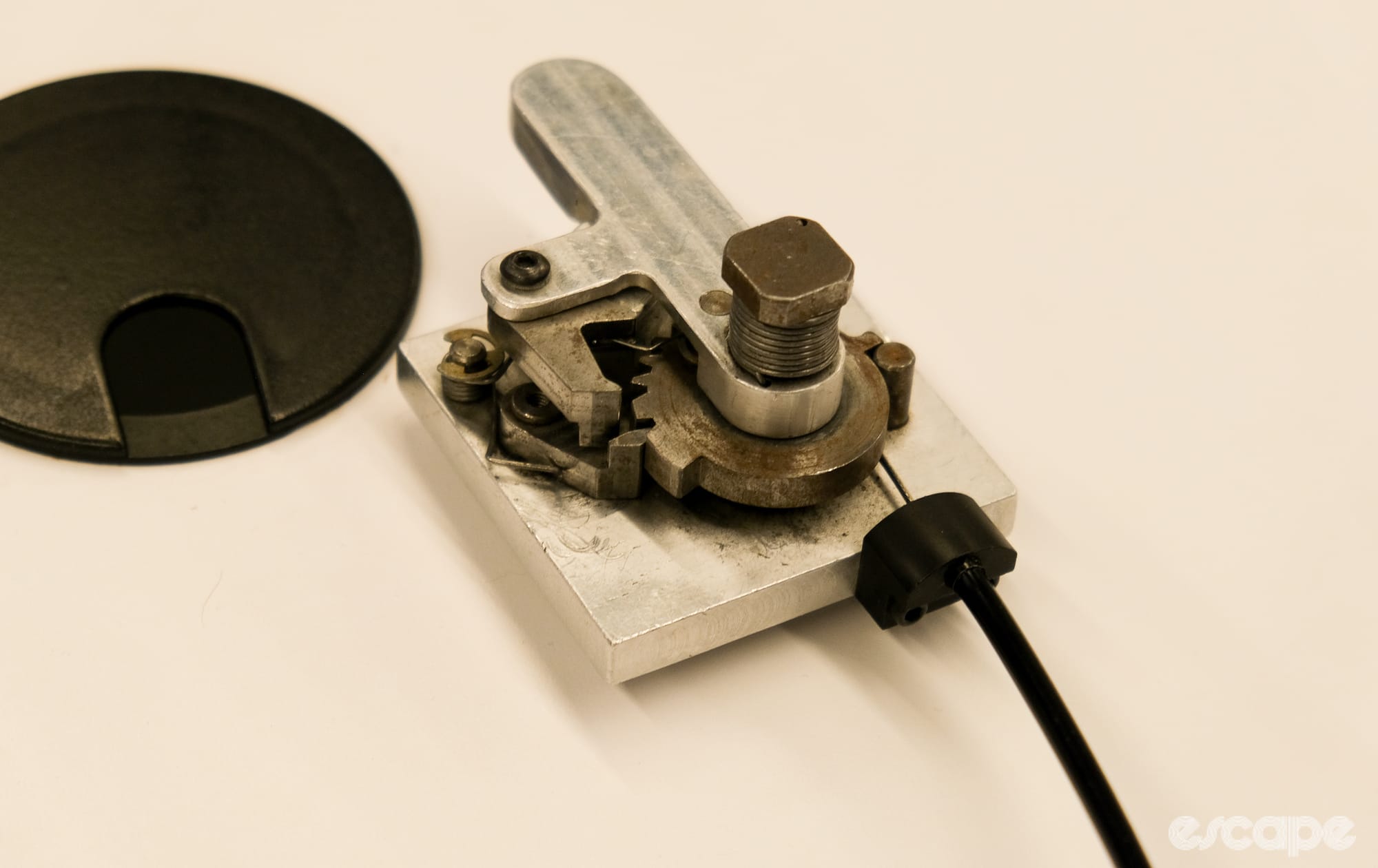

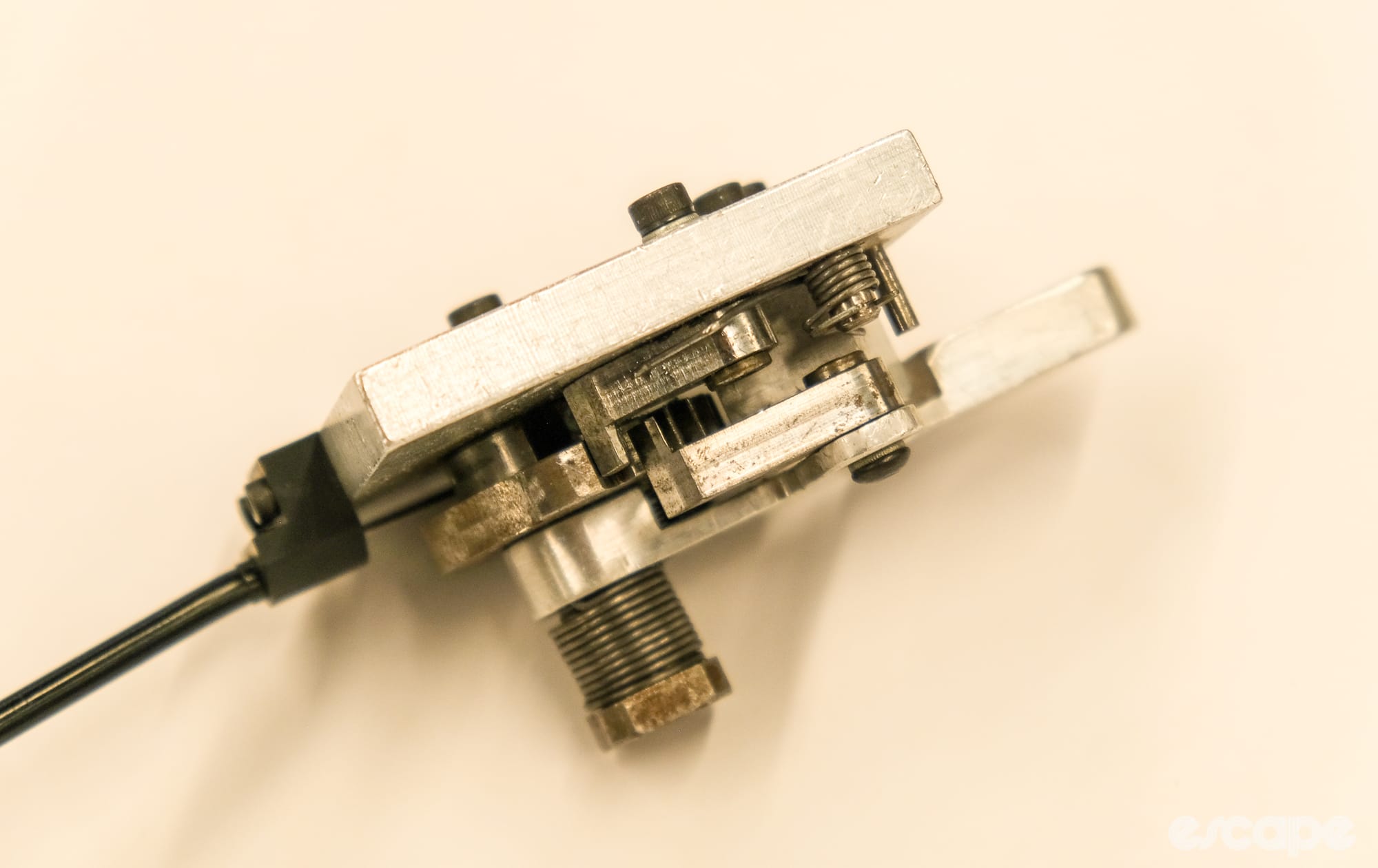

But as I learned on a visit to SRAM’s Chicago headquarters this week, just because they haven’t released a product doesn’t mean brands aren't listening to customers and trying things we would like to see. Voice-activated shifting, a brake rotor with an integrated power meter, and self-charging derailleurs are all stuff you may have thought about. And it's all stuff SRAM has prototyped and tested. In fact, as we’ll see here, it’s only in exploring, prototyping, and testing these ideas that a company can then decide whether it has promise or is destined for the bin.

SRAM’s Advanced Development (AD) division does much of this exploration work. The AD team isn’t a conventional R&D department. It doesn't exist to refine the next iteration of a derailleur or suspension fork. AD exists to dream and explore. More often than not those dreams lead nowhere, as evidenced by a box full of prototypes Kevin Wesling, SRAM’s Director of Advanced Development, dumped out on a table in front of us. But it’s in this freedom to explore that AD sometimes has the opportunity to change the shape of cycling.

From wild and wacky to standards-changing developments, SRAM AD is cycling’s equivalent of Q Branch: a team that gets to play make believe with bike parts, 3D printers, and the future of bike design.

What is Advanced Development?

Advanced Development sits a few steps upstream of SRAM's traditional product development teams. The remit is loose: Chase ideas. Figure out if there’s any merit in them.

While product managers provide most of the strategic direction, AD is also a bit of a sandbox for early concepts, and often acts autonomously in the very early stages of innovation, especially when the rest of the company isn't yet structured to support the idea.

As one team member put it, “We worked on electronic shifting before SRAM had any electronics at all. The derailleur team couldn’t have done that, they were mechanical engineers.”

AD doesn’t run on deadlines. As Wesling explains, one engineer worked solo for nearly five years on what became the Flight Attendant system. That freedom is the key here. And the madness.

The more I listen, the more I think working in AD is akin to how kids might dream up new toys, but with the resources and capability to make those dreams a reality.

Comical failures

As joyous as building toys only limited by imagination sounds, there is a serious side to all this. By the late 1990s, SRAM had become the “twister company” off the back of their iconic Grip Shift system, but this was a problem. The company had tried various iterations of a similar concept and found itself in an arms race with Shimano as the two battled it out for supremacy in the land of “gear indication.” Displaying what gear the rider was in was seen as the holy grail at the time and both companies had come up with takes – some good, but mostly terrible – on the best solution.

At some point everyone realised none of this really mattered, and Wesling switched focus. SRAM needed to ditch the "twister company” tag and refocus on becoming a “shifter company.”

The first DoubleTap prototype was almost laughed out of the room.

DoubleTap

That refocus manifested most clearly in SRAM’s first road groupsets and the DoubleTap shifting technology in particular. As Wesling explains, so much of product development comes down to patents, especially when it comes to shifting. SRAM had considered returning to the Grip Shift-style mechanism first used back in the 80s on road and triathlon bikes, but after exploring that and alternatives, it eventually landed on the now-familiar single-lever, dual-function DoubleTap logic.

DoubleTap came directly from Wesling’s team, but it started life as a prototype that got laughed out of the room. “One guy said it was the stupidest idea he’d ever seen,” Wesling recalls. “But once people rode it, they got it. And then we built an entire road group around it.”

Did we do a good job with this story?