For all of social media's many, many ills, every once in a while it allows something quietly remarkable to happen: someone transcends the tribalism and rage clicks to create something beautiful and positive. A haven in the doomscroll storm.

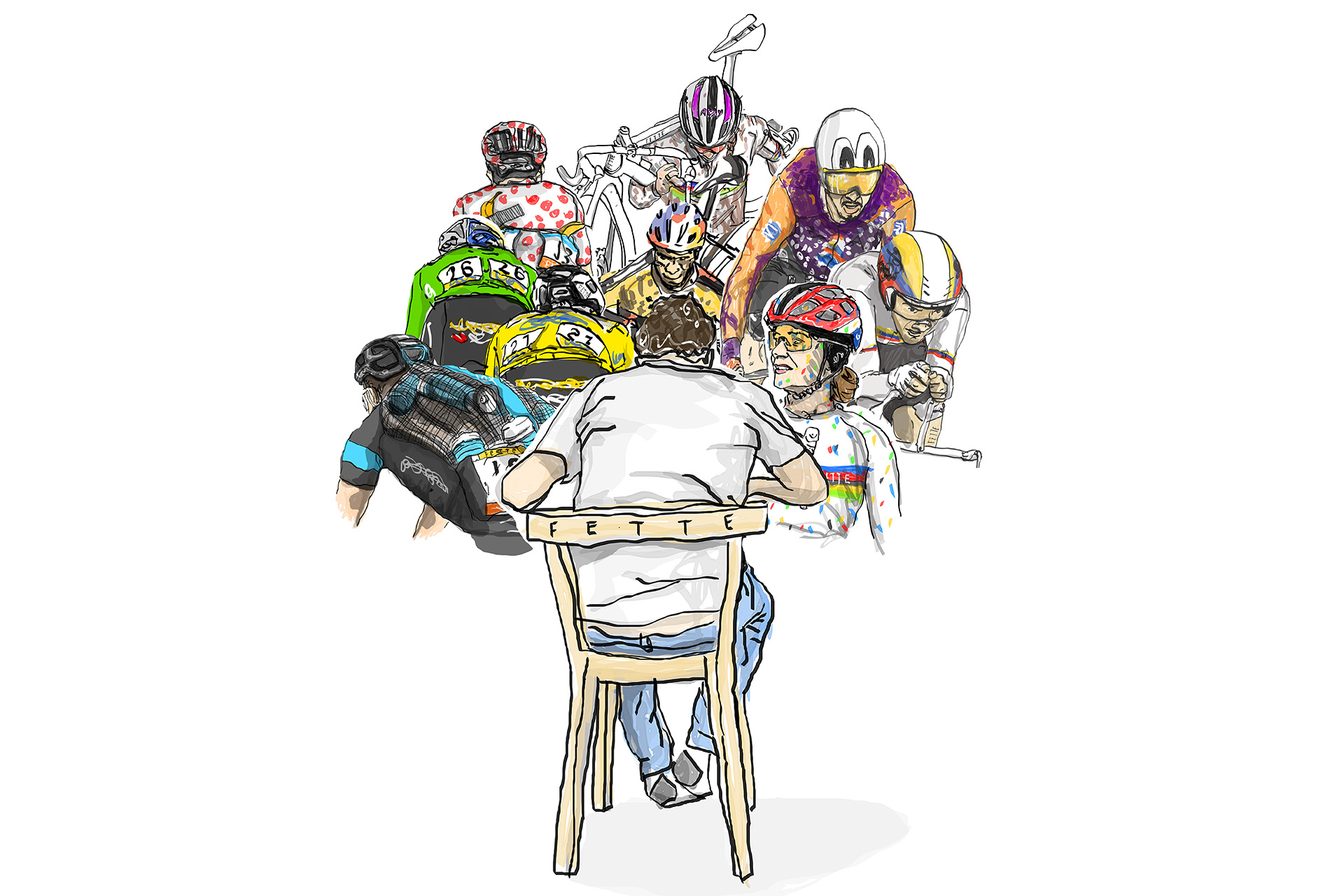

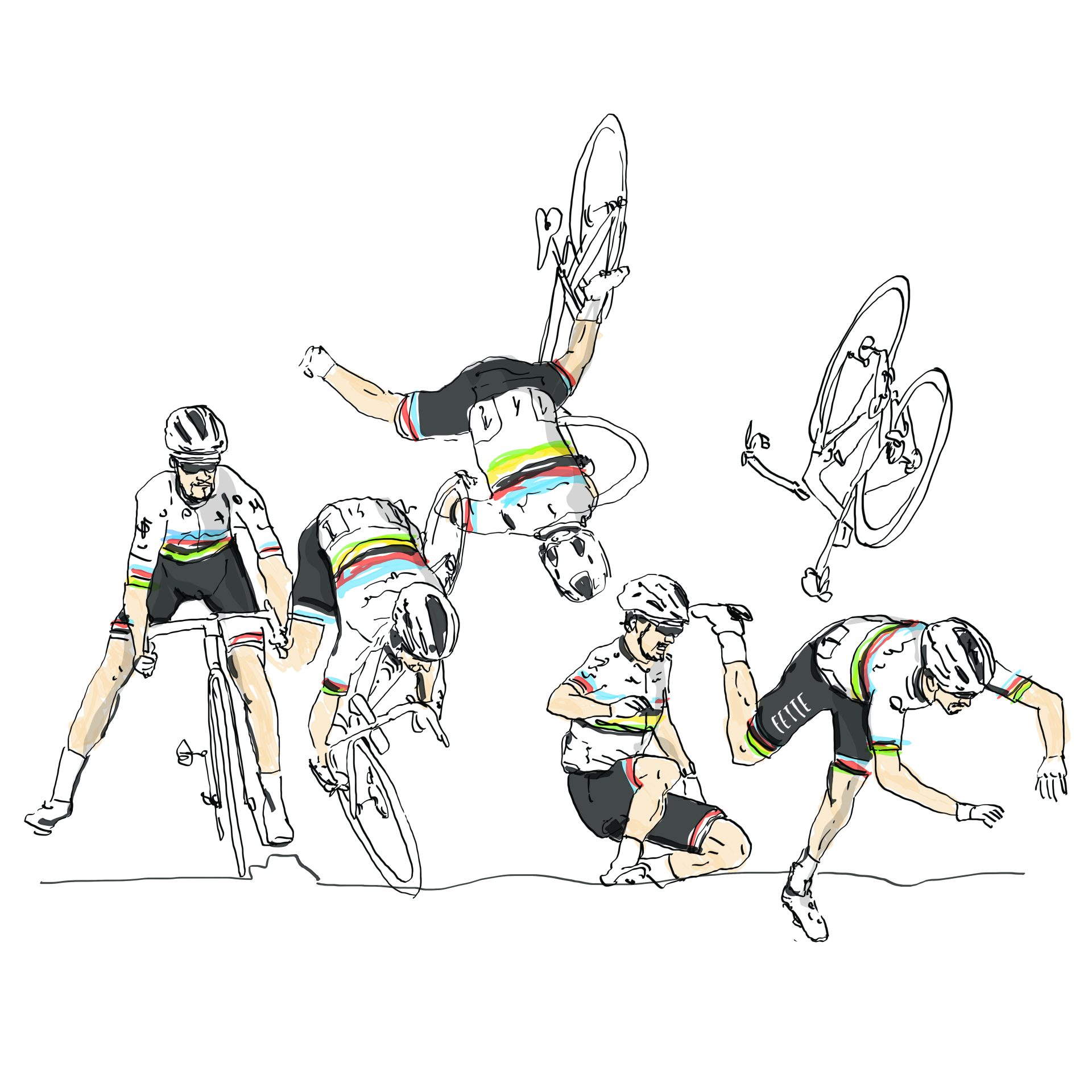

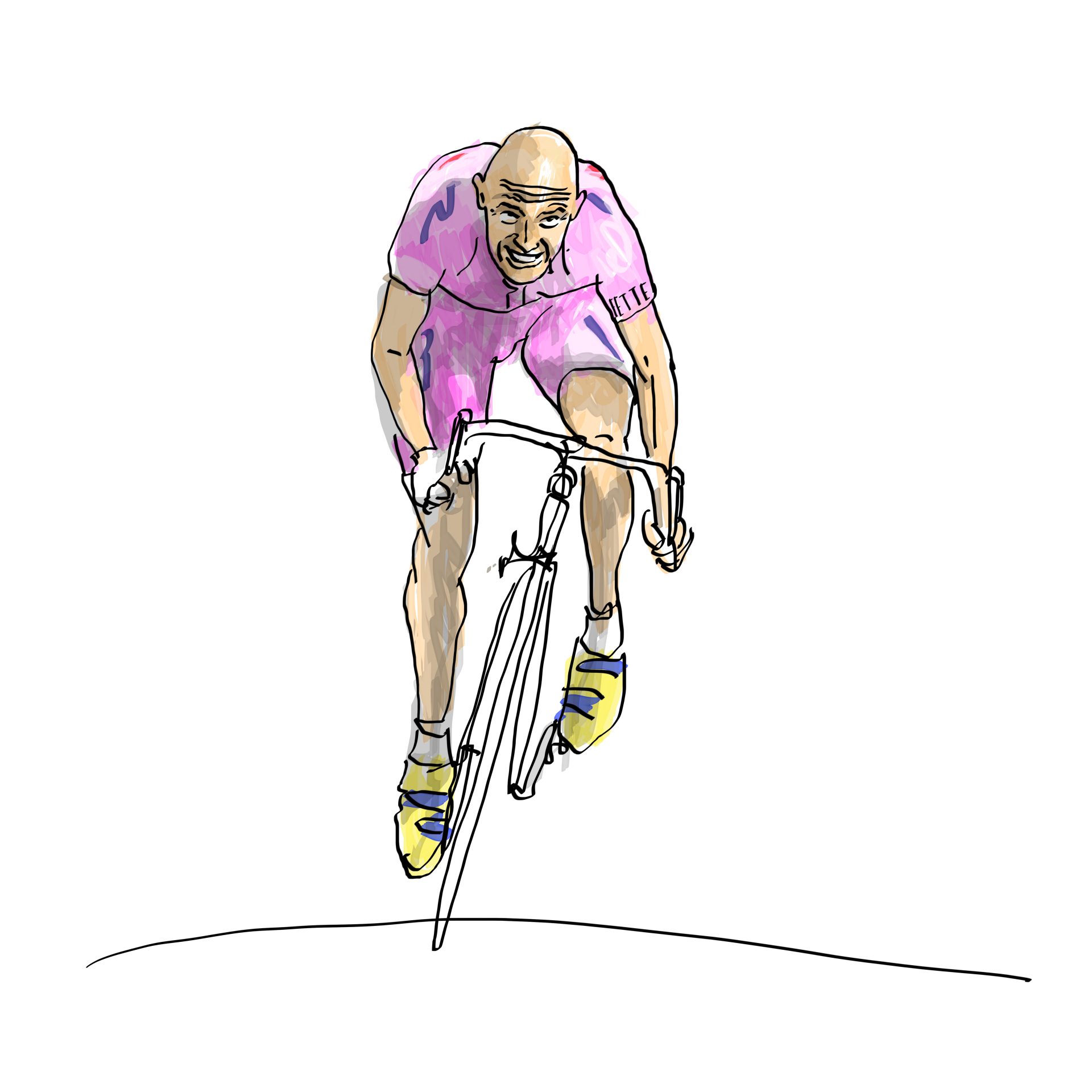

That's a bit how I feel about the artwork on the Instagram page of Fette (stylised Fe.tte), which has over several years developed a sizeable following within cycling's online community. Pretty much every day, the owner of the page creates a sharp-eyed illustration that touches on the latest happening in the sport: perhaps the winner of the day's racing, or its most memorable moment, sometimes weaving in online memes or cheeky commentary. The drawings are simultaneously simple and detailed: black stylus-drawn lines blooming to life with colour, with little details – an earring here, a motto there – that reward closer attention. It is, for the 20 seconds you might see it in your feed, a palate cleanser.

Over the years I've been following Fette, I've sometimes wondered who the person or people behind the page are – where they live, their age, whether they work in cycling, and what drives their creative spark. A nudge from an Escape Collective member on Discord (thanks @tlec!) finally gave me reason to seek answers to some of those questions, and I teed up an interview with a pseudonym. I wasn't entirely sure who to expect on the other end of the Google Meet, but it probably wasn't a bike-mad Ecuadorian architect in his 40s, currently based in Vienna.

Here, for the first time, is an interview with Jorge Larco: the artist better known as Fette.

This interview – from a very lovely, wide-ranging hour and half long discussion – has been edited for clarity and length.

Iain Treloar: So, this is the famous Fette! I didn’t know what your gender would be or how old you would be or anything like that, so it's nice to put a face to the name.

Jorge Larco: Thank you! About "Fette" … It's a nickname I have with my girlfriend. We live in Ecuador and we do a lot of cycling there. Fette is like "fat" in German, and when we are riding with my group we’re all a bit fat, and Fette is the plural – like, "fats" – so that’s the reason of the name. We wanted to use a kind of a name that is a bit anonymous – you can imagine it’s only one person, or a lot of people. I preferred not to put my face anywhere, and I think this is the first time that someone saw me …

IT: Really? I’m honoured.

JL: I don't know if it's an honour, but it's like this. [laughter]

IT: Would you like to remain anonymous for the purposes of this interview? Would you like me to write that I'm talking to Jorge, or would you simply like to remain Fette?

JL: It's okay for me – Jorge and Fette, it's the same. Right now you are entering into my space, so we are now a bit closer.

IT: Okay – so you are Jorge, and you are Fette. You mentioned that you like the fact that it's a little bit ambiguous as to whether Fette is just one person or multiple people, but the actual artwork – is that just your work or is it a collective of people contributing?

JL: No, no … it’s only me. My girlfriend helps me sometimes to coordinate some things but I do all the drawings. Yeah, it's just me.

IT: So you've obviously got a pretty big following now, with almost 83,000 followers on Instagram – I don't know if you're on other platforms, I just know you from Instagram – but that's quite an audience. When did you start the page, and has it been quite a steady growth? Were there any sudden spikes where you were like, "Whoa, people are paying attention"?

JL: Yeah … [thoughtful] I really hate social media, actually. I don't have personal accounts, because for me social media, it is not real. Fette started in the pandemic: my girlfriend moved back to Austria in 2019, and I was going to join her in 2020, but throughout the pandemic, I couldn’t go, and so I started the page as a project to be in contact with her. If you look at the first content on the page, it was just some little illustrations – like a stick drawing with a little angst, emotion – and I started doing this, but I was like, "OK, I have to put my work in focus."

Then in Ecuador – I’m from Ecuador, I’m an architect – and in [the] pandemic all of Ecuador stopped. You couldn’t do anything … it was four months that you have to stay, like, in a jail. It was a really difficult time in this moment.

I was doing a lot of cycling in 2018 and '19, but for the pandemic I had to stay at home. To feel alive, because I was alone there, I started riding a lot on the rollers and drawing a lot. I started uploading animations, and then one of my friends who was a Castelli dealer asked if I could do an animation for Castelli. But the page was still little, little, little. I remember I celebrated getting 101 followers – that was really amazing [laughs].

In December this guy suggested that I start doing the highlights of cycling and I thought, “Wow that’s a good idea, could be." I’m really, really shy – that’s the reason I don’t put my face in my work, because I don’t want the pressure – but I started drawing and one day drew Chris Froome on Ventoux, that time when he fell and started running. I put it up on my feed, and went to sleep. When I woke up – it was 4 AM, I had to go to work at a construction site – I saw "Chris Froome shared your content." Woah. When Chris Froome shared this I got 150 followers or something – a little engagement – but I saw that I could connect with the peloton directly. I started sharing my work [tagging in] with the big stars – Primož Roglič – and he shared it, and my followers kept going up.

Later I broke my knee and had to rest; before I was always riding, riding, riding but I had to do something so I drew every day. That became my new connection with cycling.

I've never put a dollar into publicity – all the growth has been really organic, people sharing things a little bit, a little bit, a little bit. In 2021 at some point I looked and had 10,000 followers, and I thought "Woah." Around then I started doing the highlights of the race – a kind of report, my analysis – and that’s how I do it now.

In the last two Tours de France I've had a little engagement with [Tadej] Pogačar, which was really cool. I haven't met him but I think he loves the humour – one of the topics of Fette is being really sarcastic; it’s not a common humour, it’s not easy to catch …

IT: I think also maybe one of the things that Pogačar is responding to is that you often blend in pop culture and memes and things like that – which for someone like Pogačar who speaks that kind of digital language, and has grown up in that kind of culture, is probably quite appealing.

JL: Yes, yes. And the great thing with illustration is that I have to react really fast to the passion of cycling. My work, if I can define in one or two words, it’s "passion" – passion for cycling. In one race I can be smiling, crying … I can connect my ability to draw with these things. It’s really nice to communicate my point of view of a situation.

IT: Have you been a cycling fan for a really long time?

JL: I was actually a hater of racing [ed. as opposed to the act of cycling] in 2017, until I started dating my girlfriend in this time and she was doing triathlons. [At first] I thought it was so boring, but then started seeing that it was cool. I’ve been passionate about cycling since 2010, and started doing a lot of kilometres – always alone, I don’t like riding with people – and I’m not a competitive man, but in 2018 I saw the first win by Richard Carapaz at the Giro d’Italia and started watching other races. I saw that I could learn something from these cyclists. Cycling is a science – we don’t think of it that way, but it is – so I started learning more about riding from watching races.

In the pandemic and after the pandemic there was a lot of people in Ecuador getting into cycling, and that’s been really good to bring more people into the sport.

IT: You mentioned Richard Carapaz before – was there a big bump in people getting interested in cycling because of his Olympic gold medal?

JL: Actually, I think he doesn’t know the impact that he had on Ecuadorian society – he never realised that he had the power to change the situation in Ecuador. I’ve never spoken to him, because he’s really different – he’s from a tiny little village, and I can’t understand what he went through winning that medal, going from 0 to 100 in fame. After Richard Carapaz, Ecuador changed a lot – during the pandemic was the very best years of Richard Carapaz, and all these people went and got road bikes, started doing exercise, triathlons ... it was really nice but it wasn’t organic cycling growth.

There’s a bit of a disconnect – what I want to put in Fette’s illustrations is the passion of professional cycling, and those professional cyclists are real cyclists; you can’t buy a rainbow jersey or a gold medal, you have to earn it. But Carapaz was an explosion for us.

IT: With the political unrest in Ecuador at the moment, is that in a way an opportunity for the future? I’m thinking of the situation in Colombia in the '80s, '90s, and how there’s a fertile wave of Colombian cycling now …

JL: Cycling is very special for us. It’s a way that you can shine – Nairo Quintana, for example, is from a very small town, almost the same situation as Carapaz, with nothing to do there – so you have to find something to do. And geographically, you are in a really special position. Imagine if you had to climb the Tourmalet to buy things for your breakfast, at an altitude of 3,000 m above sea level. This is how it is for me in Quito.

For Richard Carapaz to beat Wout van Aert, Tadej Pogačar [at the Olympics], it’s really really impressive. I can draw some parallels with the violence in our country and cycling … we always live in a stressful situation in South America. It’s social problems, it’s natural phenomena – eruptions, el Niño, blizzards … South America is really heavy. The cyclists in South America are better not because of training, but because they have a strong mentality to get over the difficulties in their situation. Like Rigoberto Urán, whose father was killed by guerillas and he focused on cycling to secure a better future for his family.

One of my favourite Latin American cyclists is Egan Bernal, who over the last two years has gone from being almost dead to doing a really great race on the weekend. That, for me, is cycling – not winning races, but showing inner strength.

IT: One of the things I like in your art is the way that it shows cycling as a microcosmic view of life – a small version of the big things that happen in life. I think your art communicates that really well.

JL: That’s a really nice point of view – I’ve never seen it that way myself. I think most of the drawings reflect my own situation – my life through the lens of this race.

Sometimes I don’t do the winner, but draw a situation that was really fun – for example at the Tour de France where Jumbo-Visma had a lot of problems on the Roubaix stage swapping bikes and running around. At that time I was here in Austria, and I had a lot of problems getting into the society. Austrians are really, really ... Austrian [laughs]. I had a lot of big problems, issues in my head, going to Deutsch lessons – you can imagine, learning a new language in your 40s, it’s not a good idea – in a country where you know nothing to do. I arrived back at my house, was riding on the rollers, watching that stage thinking, "What’s happened here? Everything’s fucked, and I don’t know how they can fix it." And then, even after that, Vingegaard won the Tour de France.

I don’t know if it’s like this with you when you’re writing, but life is sometimes like a big climb and you wonder "Why am I here? what am I doing?" But when you finally achieve what you’re working toward and stand at the summit you can look around and feel [big inhale], "I am the biggest."

IT: Can I ask about the actual process of your art? You’re watching a race and you’re on the rollers and you see a moment and that’s something that you want to convey – what’s the actual journey from that point?

JL: When we’re in a Grand Tour, I’m trying to see all the race, because it’s in the little details: I have to put the perfect details, and that’s why I watch on the rollers because then I’m really focused. When I see something, first I search for an image and create a collage of pictures to get a reference, then I start putting it together – and if I’m relating it to pop culture or an art moment, I start thinking about these things. If nothing special strikes me in a race, it’s a worry for me, because then I have to be more creative. Right now it’s pretty easy because of social media – I have a lot of followers, and people send me ideas – but the epic thing with Fette is the timing.

I don’t particularly like my drawings. It’s not that technical ... I don’t know how to explain it – it’s my personality in the drawings, but I want it to be more perfect …

IT: You’re not satisfied with the quality of them, is that what you mean?

JL: No no, of course I’m satisfied with the quality of them, but the kind of drawings that I like … when I was younger I had my punk band, and I really liked jazz or funk but I couldn’t play funk …

IT: So the drawings are your punk music, but you look at jazz drawings and you’re like, "I wish I could do that."

JL: Or funk, because jazz is so classy – it’s not that I’m not happy with my drawings, my drawings are an extension of my personality. I’m really simple, tiny lines, lots of colour, not too much information. I never put a position in my art, though. I don’t want to be pretentious and put my point of view.

As for time, sometimes I take one or two hours. Sometimes, if I have nothing to do, a drawing can take eight hours if there’s a lot of details, a lot of characters. You can find in my [Instagram] profile a lot of detailed drawings – I like Marco Pantani because he was like a punk rocker, so all my Pantani pictures have a lot of detail.

One of my favourite drawings is of Pogačar – it’s a recreation of a Picasso "blue period" piece based in the moment that Pogačar realised that he’d lost the Tour. I love these kind of recreations of art – it took a long time, finding the reference points, finding the details.

IT: So how long did that one take?

JL: Four hours. When we are in races, I have to work really fast, but if there’s no news I can take more time, put aside other things – put to rest my official work in Ecuador – and "go to a meeting" and have an escape to do work.

IT: Do you set yourself a goal of doing an illustration every day?

JL: No – but the last year I have a schedule. Right now I’m living here in Austria [with my girlfriend], but I don’t know if I’ll stay here: it’s really strange. I’m working through it in my head if I have to return to Ecuador or stay here. Staying here, it’s good for me, because things happen here in Europe, but it’s not easy to get comfortable here …

IT: So you’ve moved to Austria for love?

JL: Yes, but it’s not as easy as just love. You have to find work and things too. It’s like cycling: a mountain you have to climb.

IT: How different to your work with Fette is your work as an architect? Are there transferable skills, conceptual drawings where you’re doing illustrations and designs with a bit more flair, or are you doing the actual floor plans?

JL: Actually, I’m a weird architect in Ecuador because I don’t construct within the law. I do my drawings, my 3D models, but I never construct with plans. I’m always changing the spaces, or the client is … in Ecuador, it’s really important to understand that the architects also construct the building. It’s not like in Austria or Australia where you have a professional that constructs and an architect that plans. In Ecuador I have to construct and I have to plan.

IT: Are you contracting builders, or are you the builder?

JL: No no, I’m the builder. I constructed my own house – it’s really beautiful because you can figure out everything in your imagination. Fette is in a way like my profession, doing things in the moment, the very best I can do in that moment.

My last construction was in the last few weeks before I came [to Austria]. I designed one of the biggest bike stores in Ecuador. I’m a community manager of this store, social media, I do all the graphics, the photography … in Ecuador you have to fund your job, to do a lot of things. You have to be a rouleur. My last construction was like a Fette in architecture; it was a cycling store with a lot of thematic situations. The bathrooms are with polka dots on the walls. All the plumbing and electrical piping was painted like a UCI flag.

IT: Do you have any particular goals with your art? Can you monetise Fette, make it a job, or are you just happy to have this creative outlet to express a different side of yourself?

JL: That’s a really hard question. The last year I was actually able to live off Fette, I engaged with Jumbo-Visma for some works, also Bora-Hansgrohe … my first ever client was ASO, for Tour de France Femmes. Imagine that: my first client was the biggest one in the sport! It was like going from being a student to being an astronaut.

I’ve started growing the business side of things. It’s difficult, because I’m not always in Europe – but I’ve also started working with BetCity, the Jumbo-Visma sponsor, as well as McLaren, and sometimes I sell some illustrations. I really want to live off my art because from the last three years, every day I’ve been drawing.

My dream is to paint bicycles, and I have some propositions from brands to do shirts and jerseys, but I want Fette to be special. When I sell my illustrations, I sell them only in special editions of 13, because my logo is an upside down 13. I don’t want to be massive …

IT: Is there a fear that if it becomes more of a job, the joy gets drained from it?

JL: Yep. Yes. Definitely. When I start getting super worried, or stressed, I stop the thing. I don’t want that.

For me Fette is kind of a gregario. When everything is bad, it's like Fette arrives and enters the battle and says, “Alright motherfucker, you can do it, you can do it." For the last two years Fette has been like that for me.

Some people tell me, "You’re really famous," but I tell them no, I’m not famous, I just have a page with a lot of numbers. Sometimes life’s good, sometimes it’s bad, but I put up an illustration every day and people like it.

Did we do a good job with this story?