In this final instalment of an introductory guide to power, we look at some of the caveats for training with a power meter. As much as power is an objective measure of rider output, sometimes the numbers we see on our head units might seem too good to be true or make you feel weaker than ever. Understanding when to take your power readings with a pinch of salt gives you a more rounded and nuanced understanding of your training data and most importantly it can help you maintain a healthier training relationship with your data.

Read the other entries in our Introductory Guide to Power series:

Finding the right power meter for you

Baseline power testing

Understanding the data

What is power zone training?

To help explain the limitations of power meters I have enlisted the help of Shane Miller, more affectionately known as GPLama, who has put more power meters to the test than I have had hot dinners. His scientific approach to product testing provides him with a unique perspective on the topic of power meters and when the data they give should be called into question.

Trust your gut

If you have used power in the past or if you have used a smart indoor trainer, you will have a rough idea of what are reasonable power numbers to see. Any significant, sudden change in these numbers is cause for concern as although your power curve will vary over time any jumps of more than 10% are hard to attribute to just a good day on the bike.

Miller says, “If you're training with power, and you've trained with power for at least a few months, you know your zones, and those zones never really change a lot. So you know your five-minute and 10-minute powers, then you know what you can do up your local climb.

"If those numbers are high or low by probably about 10% you know something might be up. I think as cyclists, we're now at a point where we're really in tune with what we're seeing and the numbers presented.”

Another way you can get a general feel for the accuracy of your power meter is on a group ride. If you are riding with someone of a similar weight up a climb, the power you are riding at should be similar. It is a clear sign that one of the power meters is not accurate if one of you is riding at a claimed 300 watts and the other at 360 watts. If you have a third rider of a similar weight, you should be able to confirm which one looks to be the outlier.

Human error can lead to unreliable data

If you are new to using a specific type of power meter it is important to familiarise yourself with its specific installation requirements. Pedal power meters for example need to be installed to a specific torque value and some require washers between the pedal and the crank. Without these, the reliability of the data you get can be compromised.

Another consideration for pedal-based units is making sure that you input the right crank length into your head unit. Miller explains that the crank data stored in a head unit will override the crank length set in a mobile app. If you find yourself moving power pedals from bike to bike this is something to be particularly conscious of as it is likely that not all of the cranks you have will be the same length especially if you move them between road and gravel bikes.

- Read more: An introductory guide to power: Baseline power testing

If you have swapped your pedal power meter from bike to bike and are immediately seeing power readings that don’t add up, the installation torque and set crank length would be the first places to check.

Manually offsetting your power meter before a ride is beneficial. Even though many of the latest generation of power meters have what is called auto zero, it is a good habit to manually offset. On this point, Miller says, “Even if it's got auto zero, you should always be doing a manual calibration every few weeks. I wouldn't truly rely on auto-calibration working because how it works for different meters is different.

"After 18 months I'd be looking to fit some fresh batteries, check for firmware and make sure there's no weirdness when you do an auto-calibration.” With this Miller means that when you replace your battery and calibrate your meter the zero offset figure it provides should be closely matched to what it was before.

It is worth noting that some head units will give you the option to manually calibrate the power meter. This is a little misleading as you are simply zero offsetting the meter, similar to zeroing a set of kitchen scales. Although it is called a calibration, this is not technically true as a calibration would require hanging a known mass from the meter that will generate a load that can genuinely calibrate the meter. In this sense zero, zero offset, offset and manual offset are interchangeable. In most cases, calibration is also used to describe offsetting especially if it is done via a head unit.

The final point that Miller makes clear is that riders need to ensure that they are correctly zeroing their meters. “People need to know how to properly zero the meter in the correct way. To zero all power meters the bike must be stationary with the rider unclipped from the pedals but there are a few specific considerations depending on the type of power meter that you have. A pedal power meter can be zeroed anywhere, it doesn't matter where in space it is. A crank-based meter needs to be so the crankarms are aligned vertically.” This is so there is no load going through the meter when it is zeroed as this would be the same as zeroing a kitchen scale with a bowl on them. Everything you measure after this will be affected by that incorrect zero reading.

Power meters need to bed in

All power meters need some time to bed in, whether it is a new bike that came with a power meter already installed or you have recently fitted one. Going out for a short ride with some high-intensity bursts should settle everything in. Miller says, “You need a few stomps on them just to make sure everything is bedded in and everything is meshed correctly.

"If people are doing their own wrench work and the [meter is] not quite torqued to spec, it might need a few sprints to get those pedals correctly cranked down," Miller adds. This is something to be particularly aware of if you frequently move your power meter from bike to bike. This can be a real issue for riders in a zone 2 block; without any high-intensity efforts to settle the meter it can potentially read incorrectly for multiple rides. This is especially true for riders who are predominantly indoor training as there are no junctions or traffic lights to sprint out of that would naturally bed the meter in.

Single-sided meters are power estimators

Previously in this series, we have looked at the range and types of power meters are on the market. At the more affordable end of the spectrum, single-sided pedal and crank-based meters estimate your total output by doubling the measured value of one leg, typically the left. This does leave a large potential for error. The potential for left/right muscular imbalances means that almost everyone has some level of discrepancy between the power produced by their left and right legs.

On this topic, Miller explains that it is not as simple as offsetting your power to compensate. “If people always say, I'm always 51%/49% or I'm always 50%/50% they're not. After four hours, you're sloppy. You're 55%/45% and that changes. It's a variable.”

He goes on to say that with a single-sided meter, that imbalance "can't be measured either because it gives you one figure. So, you can't tell. There's always that question of when people buy a single-sided meter, they're like, 'Oh, is it [giving me a true power reading]?' if you ask the question, buy the dual-sided [one] because you'll always be wondering."

It is important to understand the limitations of single-sided meters and how you can interpret the data. I know through my own experience that when I use a dual-sided meter my power sits on average 2-3% higher than when I use a single-sided meter. The other issue that riders can fall foul of is biasing their input on the side where the power meter sits. This can lead to muscular imbalances but it will also give you a false over-reading. Some riders subconsciously end up biasing their output in this way, especially to achieve a higher power reading. If this is the case the best solution is investing in a dual-sided meter or a spider-based alternative.

Does your power meter have active temperature compensation?

Most power meters today have a feature called active temperature compensation with meters that have it listing it as a feature within the specs found on the manufacturer's website. This uses an internal thermometer to measure fluctuations in temperature and compensate the reading accordingly. The strain gauges used to measure the force applied to a crank, spider or pedal have a small tolerance. This means that changes in temperature will cause the mounting material to expand or contract which has an effect on the meter readings. To prevent your readings from fluctuating along with the temperature, brands developed active temperature compensation that automatically adjusts the reading based on those changes during a ride.

If you have a power meter that does not have active temperature compensation then you will need to be aware of changes in the environment. As the temperature changes or if your power reading begins to drift beyond what you would expect to see it is best to stop and perform a manual zero offset.

Power meter manufacturers will normally specify the range that active temperature compensation can accommodate. Beyond this range, the meter will be unable to automatically correct for the changes. The simple solution in these instances is to perform a zero offset.

Something a lot of riders are likely guilty of without even realising is zeroing their meter where their bike is kept. If you keep your bike in the house it is likely to be at around 20°C. If you are heading out for a summer ride where the temperature is around the mid-30s or a winter ride where the temperature is around freezing this is too big of a swing in temperature for the active temperature compensation to self-correct.

Most power meters have an active temperature compensation range of around +/-10ºC from the initial calibration temperature. If you are zeroing your meter outside of the environment you are going to ride your power meter can quickly start to misread. Instead, the best practice, says Miller, is to put your bike outside for around 10 minutes before your ride to let the components of your bike acclimate to the ambient temperature.

Alternatively, if you don’t have somewhere safe to leave your bike outside this step can be done 10 minutes into a ride, but note that this initial period prior to the zero offset could return inaccurate data. Once you have zeroed your meter you should be good to go, the only consideration beyond this is performing another zero if the temperature changes beyond 10ºC for example riding up to altitude or starting early in the morning and riding through to midday.

Get to know your power meter quirks

No power meter is 100% all of the time and there will be instances where your power meter will return incorrect data. Some power meters, like Shimano’s Dura-Ace dual-sided offering, have data errors that are well documented, but others take a bit of time to get to know.

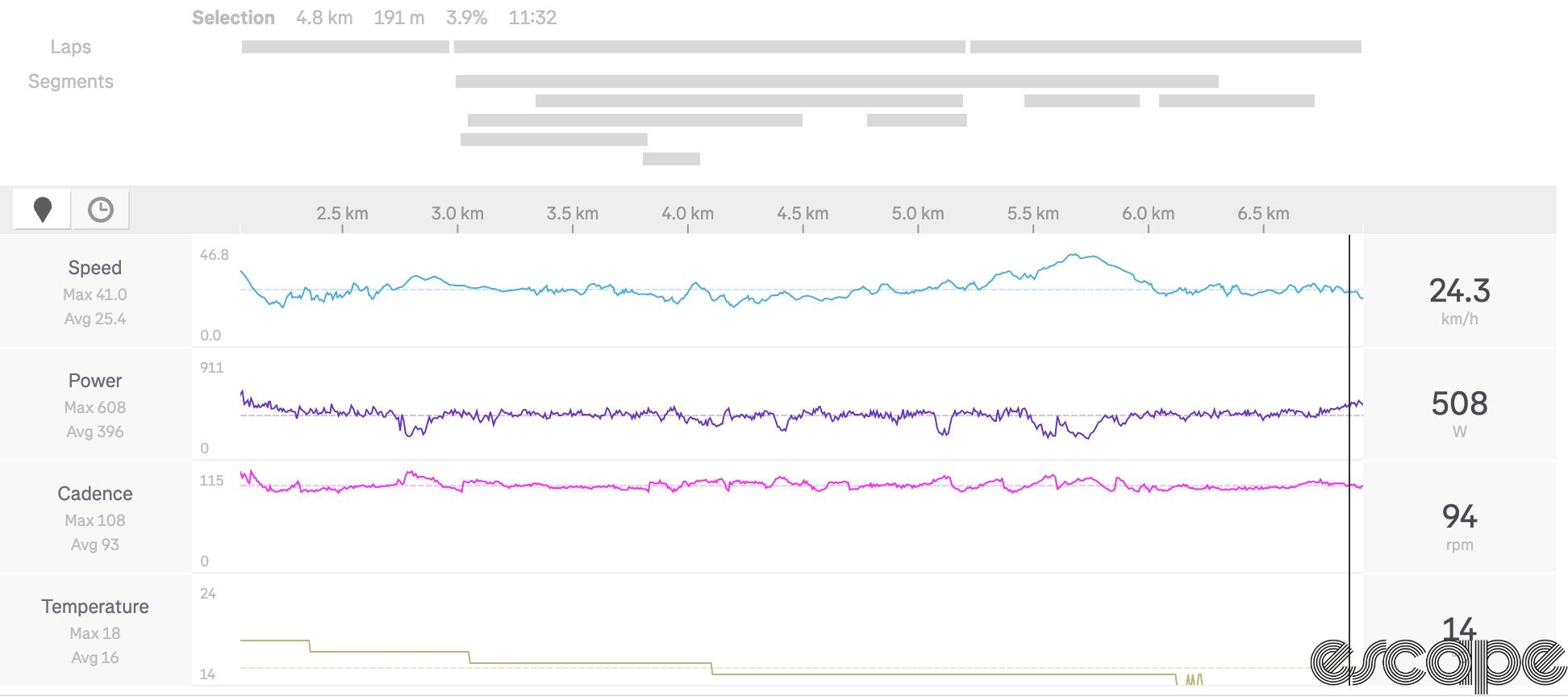

An example that came to Miller’s mind was SRM’s PC9 meter: “If you rip out a big sprint the offset changes. I can continue in a steady state, and it reads 2-3% high. I stop and zero only that meter. It comes back into line.” (Miller has used two other meters fitted to the same bike whilst testing the PC9 in order to confirm this phenomenon.)

Another example Miller notes was a Stages crank-based power meter, where he found that when a fresh battery was fitted the meter would over-read by 3-4% for a short while before everything settled back down. This was a general issue across multiple units and not an isolated case of that unit.

Miller explains that regardless of the brand or the meter in question it is always best to wait for them to be independently verified by a third party before diving in and making the purchase. Sources like Miller himself or DC Rainmaker offer independent evaluations of power meters with cross-brand comparisons to validate manufacturer claims. No matter the reputation of a brand, having a third party confirm that the meter falls in line with the brand's quoted spec is the best strategy.

Although many power meter quirks are just things to be mindful of and acknowledge, doing some research prior to purchasing a meter can prevent you from investing in something that has known issues.

Meter-to-meter comparison is an approximation

The accuracy of power meters on the whole has improved significantly in recent years. Contrary to Pogacar’s sentiment about power meters where he said, “Power meters are not so reliable these days," Miller takes the directly opposing stance. “I love that quote because that's total bullshit," Miller says. In general, power meters these days are very reliable.

“It just happens to be [Pogačar's] view of the world that's very Shimano," he continues. Shimano's latest power meters are known to have issues with the meter giving different power readings between the big and small chainrings.

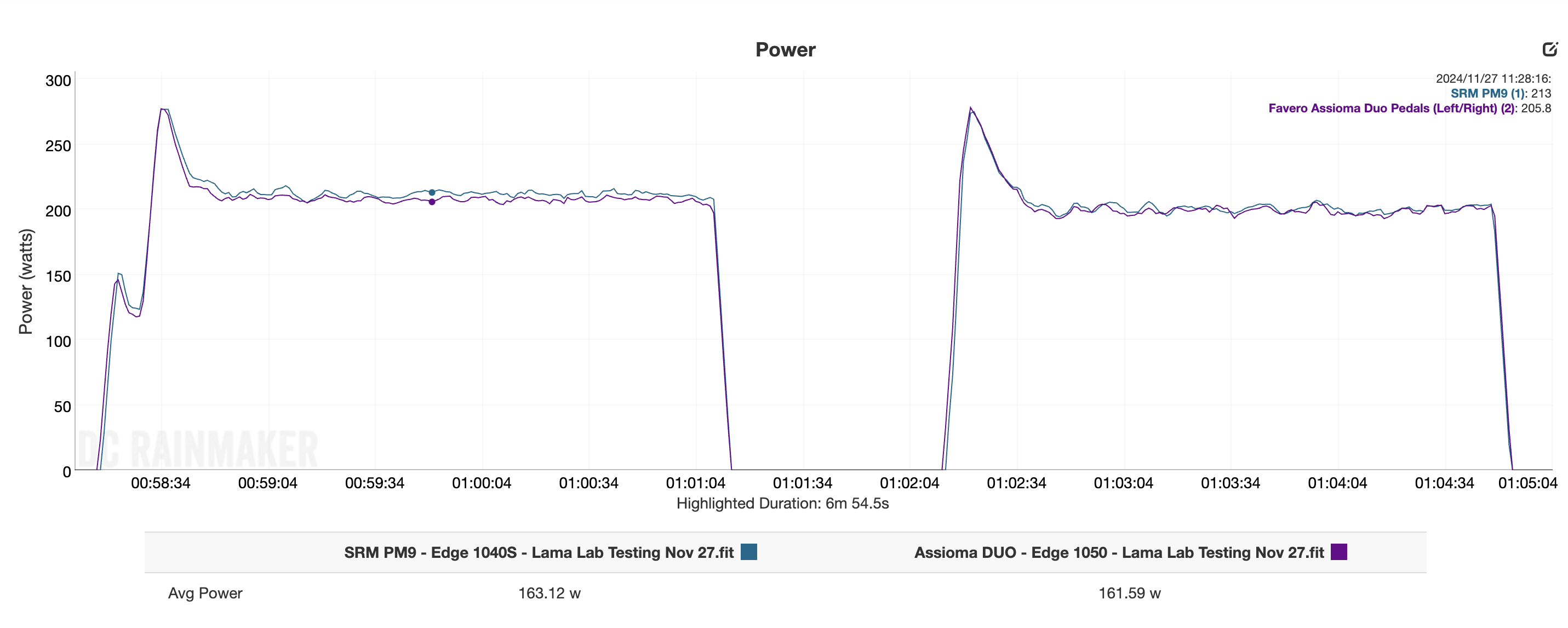

If you switch power meters or use an on-bike meter for outside riding and an integrated power meter on an indoor trainer, Miller does believe that the numbers they provide should be “very bloody close at least within spec within what they stamp on the side of the box.”

"You shouldn't be seeing anything more than a 2% or 3% difference on a trainer," Miller says. "[If I do] I'll go back to the manufacturer, they'll either replace it, correct it, or go quiet on me. Either way, above this that's too much though. We shouldn't accept any big differences these days.”

However, something to be aware of is the potential addition of tolerances. Even the best meters on the market are subject to a 1% tolerance on their accuracy, meaning that at best you could still see a 2% difference within meters. If you are using a spider-based meter with a claimed accuracy of 1.5% and an indoor trainer with the same quoted accuracy this allows for a potential 3% discrepancy, even though each meter is performing to specification.

That makes comparing data across power meters difficult, and could affect high-intensity workouts; even a 3% difference at 300 watts is nine watts – enough to turn a 20-minute FTP interval from difficult to impossible. If you are riding at a true output of 300 watts one meter could read 295.5 watts and the other could read 304.5 (if decimals were displayed).

It is for this reason that it is also impossible to compare exact like-for-like readings between two meters. If you rode up a hill at 400 watts on one meter and 320 watts on another, it is fair to say that the first effort was done at an undeniably higher intensity. As the efforts get closer it can be harder to take any conclusions, for example, if on one meter you rode the hill at 320 watts and then with another meter on a different day you rode at 325 watts this falls within the accepted error meaning that it is hard to objectively say which effort was truly ridden at a higher power.

It is also worth noting that no matter how accurate your power meter may be cyclists are not machines and we are open to daily variations ourselves. It is completely within the realms of possibility that your abilities can vary by two per cent day-to-day. This means that if you are looking for a power meter to closely monitor your ability daily then there ar other factors that also need to be considered.

To conclude

Power meters have gotten a lot better in recent years. It is far less likely for you to pick up a complete "random number generator." Some meters like Shimano’s current generation have some unavoidable issues, but for the most part power meters are now more accurate and reliable than ever. Unlike in the past, there are fewer concerns about the reliability of the data a power meter provides.

But there are still circumstances where the data you are being shown can be incorrect or irrelevant in comparison. Spending some time to understand your power meter, the data it gives you and how it relates to other power meters you have access to can be beneficial to your training.

This marks the final chapter of ‘An introductory guide to power.' If this is your first encounter with it, make sure to go back and check out the previous articles that cover everything you need to know when it comes to adding power to your training.

Did we do a good job with this story?