The curtain has closed on the 2023 Cycling World Championships, and the people of Glasgow have their city back. Across 10 days of competition, there was a vast array of cycling events, from gran fondos to road races to all flavours of mountain bikes and BMX, for both paracyclists and able-bodied athletes. But of all the disciplines, there’s one that stands out as a particularly obscure and misunderstood specimen: artistic cycling.

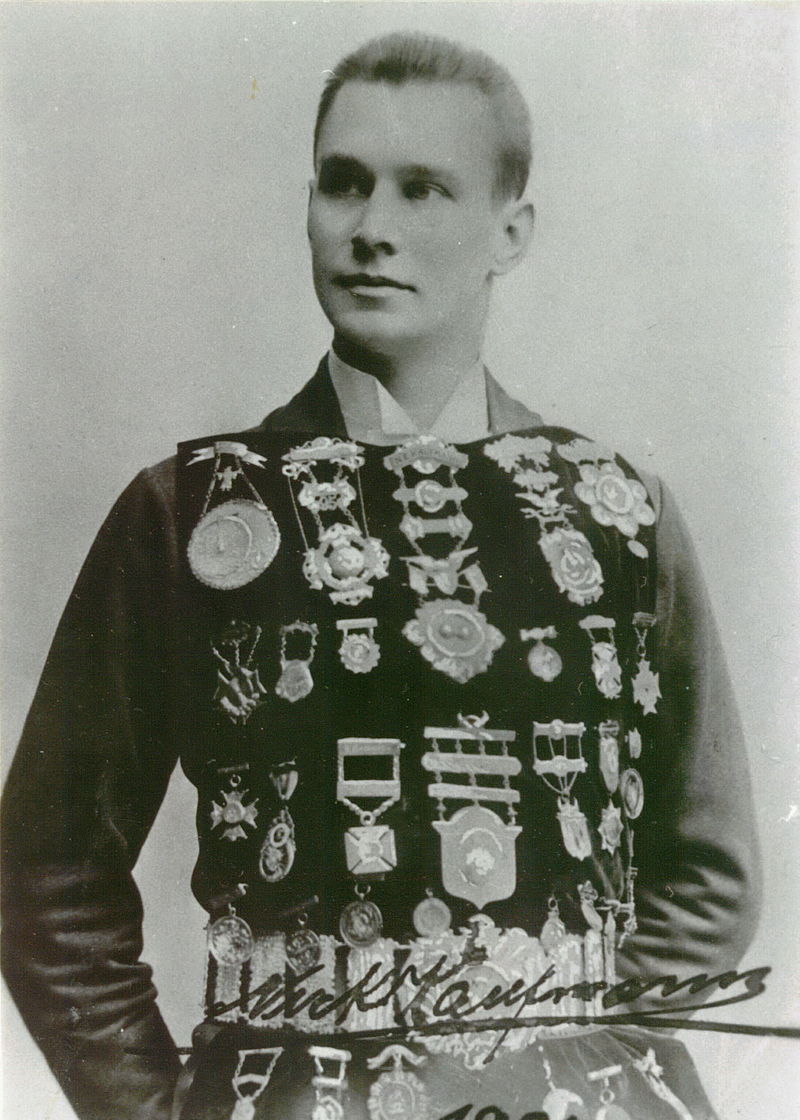

Sitting within the ‘indoor cycling’ family – a headscratcher of a title, seeing as it doesn’t include track cycling even though that is often indoor too – artistic cycling is probably best described as a fusion of gymnastics, ballet, and cycling. Its origin is credited to Nicholas Edward Kaufmann (1861-1943), an American from New York State who started cycling at the age of 20 on a penny farthing. From there he progressed to a ‘safety’ bicycle, started doing tricks, and became a champion in his field. Just look at all of his medals!

Over the course of what sounds like a truly interesting life, he then:

- toured with Ringling Brothers Circus

- managed a stunt-cycling team called ‘Kaufmann’s Cycling Beauties’

- invented the other UCI-recognised indoor cycling discipline, cycle-ball, after successfully shepherding a wayward pug with his front wheel and pondering whether a football might be a less bitey choice

- gave up on cycling to go all-in on the burgeoning sport of roller-skating

- gave up on roller-skating to become a postage stamp aficionado;

- and finally, died at an advanced age in Berlin, where he’d been living for decades.

Which perhaps explains why artistic cycling has such a firm foothold in German-speaking countries, but not why there isn’t a Hugh Jackman-starring film adaptation of Kaufmann’s life.

This was arguably artistic cycling's big moment since the Kaufmann years, with Glasgow Super Worlds presenting a unique opportunity for artistic cycling to appeal to a broader audience beyond the mid-sized Germanic towns the sport normally visits. Compared to last time I checked in on the discipline, the crowds were notably bigger and the coverage more polished, with fancy new camera angles showing off the tricks and commentators that actually spoke throughout (as opposed to, say, breathing heavily on mic for the first hour of the YouTube livestream).

The crowd at Glasgow's Emirates Arena, from what I could make out on YouTube, was also considerably more dynamic. Look at all these people that have paid money to be here!

Even the many, many stoic-faced Germans in the audience accessorised their outfits with red, black and yellow leis:

The artistic cycling program, held across the final weekend of the championships, took in singles, pairs, and a four-person team event (the last one called ACT 4, for reasons I’m not entirely clear on). Some of the events were mixed, others gender-segregated, all of them staggering in the skill level of the athletes.

Across five minute routines, the athletes complete 30 technical figures (/tricks). Like in the judging of diving, there’s a maximum possible score from the stated routine – this is called the ‘expected score’ – with deductions taken for wobbles in form, touching the ground, or going over time. If riders are feeling particularly daring they can throw in extra tricks to tactically boost their scores, but if they’re not keeping an eye on the clock this can backfire.

What kind of tricks are we talking about? So many mad things. My initial idea for this article was a running tally of how many times I would cause grievous injury to myself if I attempted a routine, but I lost count within the first 30 seconds.

Unlike road or track cycling, which are at least to a certain extent exercise competitions – achievable skills for most riders, just executed vastly faster and more gracefully – there is such a skills gap and unfamiliarity with artistic cycling that I wouldn’t even know where to begin. There is not a single thing I could do: not the handstand, not the headstand on the saddle, not the standing on the handlebars, spinning them 180 degrees, while going backwards. Every single move is impossible in a way that is difficult to articulate.

But even though literally everything about artistic cycling blew my mind a little bit, there were a few moments that blew it just a little bit harder.

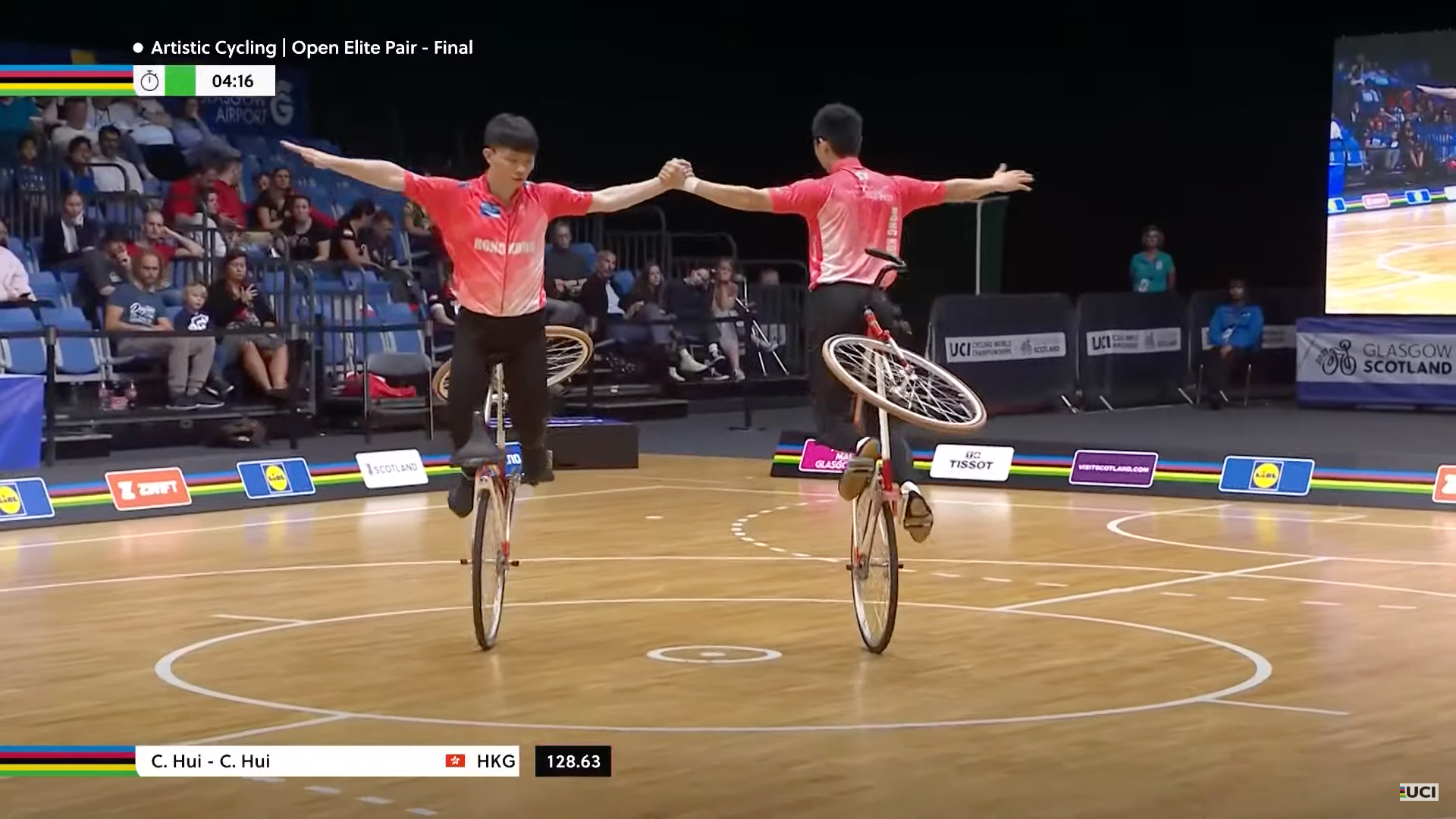

First up, the presence of two Hong Kong teams in the finals of the open elite pair final. In a sport dominated by Germany, Switzerland, and Austria (roughly in that order), this was a surprising injection of non-Germanic flavour. Adding character was the fact that both pairs were brothers, both of them with matching initials. C. Hui and C. Hui, pictured below, finished fourth overall (there are apparently no full-time professional artistic cyclists – in this case one of them is a construction worker, the other a banker). The other Hong Kong pair, T. Lim and T. Lim, finished in the bronze medal position.

Hong Kong's presence at the highest level of artistic cycling was explained away briefly by the commentators with a single line I immediately wanted to know more about: the presence of indoor cycling on the school curriculum. Granted, this does not strike me as something that has the ring of truth to it, but the official Hong Kong indoor cycling website does have a pretty comprehensive (and comprehensible) breakdown of the ins and outs of the sport, so who am I to argue.

In the same event, I was also quite taken by the German pairing of Nico Rödiger and Leah Styber, mostly because of Nico's lovely little ritual of carefully putting down a towel with his name on it on a chair on the courtside:

I also really, really liked the way that the leading team in artistic cycling doesn't sit in one of those nerdy gamer chairs that they have in Tour de France time trials.

Artistic cyclists don't have a hot-seat at all. They have hot-bean-bags:

I've also got some lingering questions about who advertisers think the audience is for this sport, seeing as roughly every three minutes I was attacked by advertising for A) an upcoming UFC bout and B) an online Madhur Jaffrey cooking class:

Mostly, though, I'm left with a sense of awe for these mostly Germanic (/a smidge Cantonese) athletes, all of whom are toiling in relative obscurity to compete in a cycling discipline that very few people care about – even the livestream of the catastrophically dull, nine-hour-long UCI Congress has three times the views.

But then, maybe the fame and the renown isn't ever the point. Maybe the motivation comes from some deeper part within oneself: the part that says, 'fine, I can't ride at obscene speed and earn millions in sponsorship and contracts ... but can you do this?'

Did we do a good job with this story?