Cane Creek has today announced the debut of Invert, a new suspension fork specifically made for gravel bikes. Yeah, I know what you’re thinking: “Suspension for gravel bikes? Really??” Worry not, I’ll get to that soon enough. But if you’re among the faction that’s already convinced suspension in gravel is a good thing – or you’re just suspension-curious – the Cane Creek Invert’s unusual format makes for a very intriguing proposition.

Comparing the Invert against the two primary high-end competitors, the Fox 32 Taper-Cast and the RockShox Rudy Ultimate XPLR, Cane Creek’s entry is pretty similar in a couple of key areas. Travel is limited as you’d expect – just 30 or 40 mm in this case – but tire clearance is very generous with Cane Creek saying a 700×50 mm gravel tread will fit just fine.

Just about everything else is different, though.

Most critically, whereas nearly every other gravel suspension fork on the market uses a conventional telescoping layout where the lower legs are connected at the top and bottom with an integrated arch and bolt-on axle, and slide up and down over smaller stanchions pressed into a metal crown, the Invert uses a so-called upside-down (or inverted, hence the name) arrangement akin to what you’d find on a motorcycle. It’s a concept that’s been tried several times in the mountain bike space over the years with varying degrees of success, and Cane Creek is echoing many of the performance benefits upside-down proponents have claimed in the past.

Fore-aft stiffness is supposedly better than a conventional layout since the larger-diameter tubes are up at the top of the crown where there’s the most bending stress, and since the seals are now at the bottom of the upper legs, they’re naturally always sitting in oil so things are always running smoothly. There’s also less unsprung weight – the part of the fork mass that’s constantly moving up and down – so, at least in theory, the Invert can be more responsive to bumps.

Perhaps more importantly, Cane Creek says the Invert’s design is a better visual match for modern gravel bikes. Nearly every other option currently on the market is essentially a pared-down mountain bike fork with the same components, same layout, and so on, just sized down, reshaped, and retuned. In contrast, the Invert’s more gently rounded shape is meant to blend into modern oversized and tapered head tubes, and while it’s obviously still bigger than a typical rigid carbon fiber fork, it retains a little more of the elegance people apparently expect to see on a drop-bar bike.

Save for the Lauf Grit SL, the Invert is also substantially lighter than just about every other high-end gravel suspension offering.

Whereas most suspension forks use a press-fit aluminum crown/steerer/stanchion assembly with cast magnesium lower legs, the Invert uses a one-piece molded carbon fiber crown and steerer with bonded-in machined aluminum upper legs and 30 mm-diameter forged-and-machined aluminum lowers. Claimed weight is as low as 990 g, or more than 200 g lighter than either the Fox 32 Taper-Cast or RockShox Rudy Ultimate XPLR.

Invert is pretty different internally, too. Both the Rudy and 32 TC feature both an air spring and oil damper with a variety of compression and rebound adjustments to fine-tune the ride. Invert also uses an air spring with the usual adjustable air pressure as well as three stages of air chamber volume tunability depending on how quickly someone wants the spring rate to ramp up before the fork bottoms out.

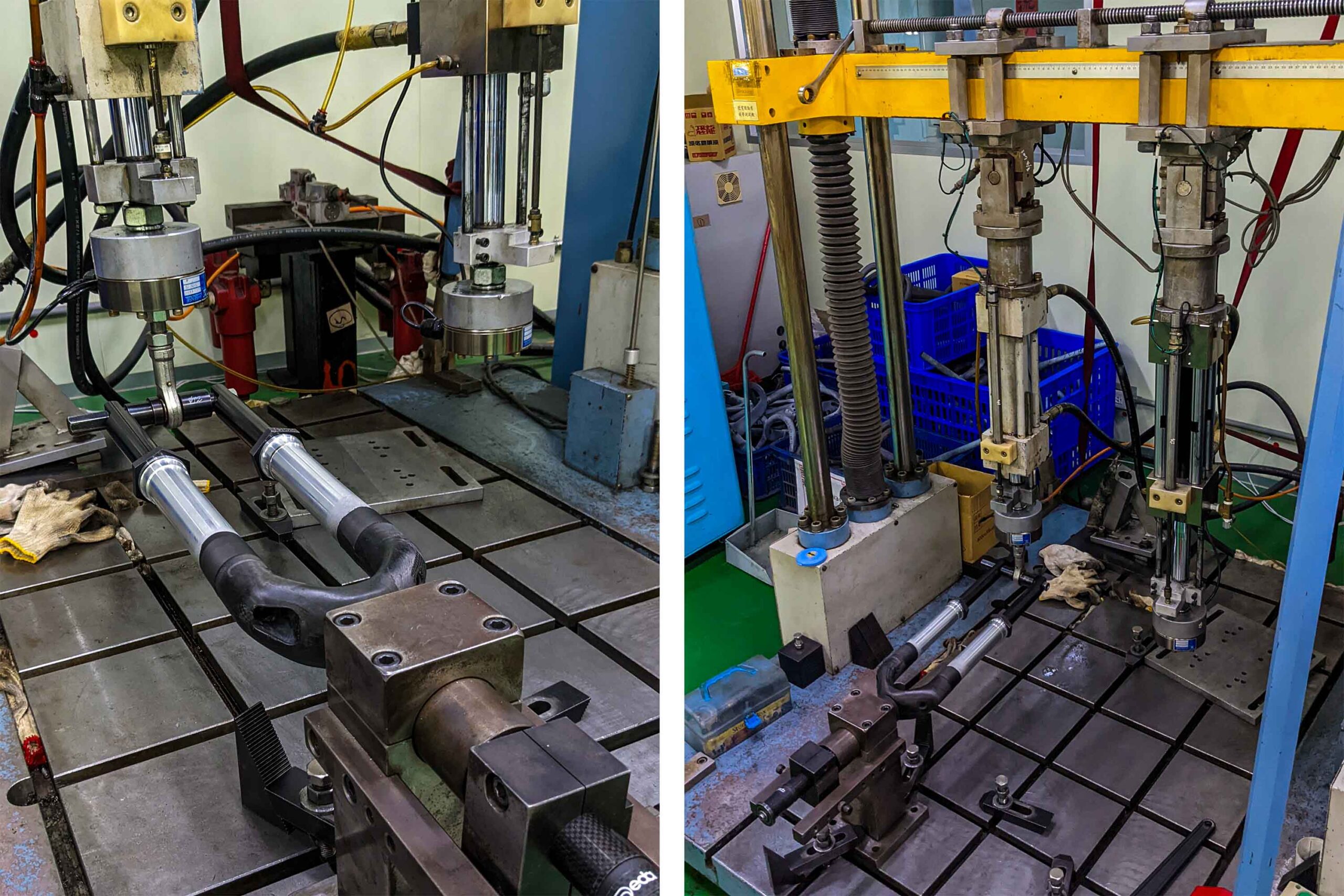

Quite interestingly, there’s no damper at all. Cane Creek says it actually built parallel fleets of development mules – one with a conventional oil damper and one without – but its test riders supposedly couldn’t tell the difference between them in terms of ride performance so it was decided to go without to save both weight and complexity.

Cane Creek will offer two versions of the Invert when it becomes available some time around late June. The Invert CS will come with 40 mm of travel and Cane Creek’s “Climb Switch” – a pseudo-lockout with a large pushbutton mounted on the crown that will open and close a hydraulic valve (although there’s oil flowing, this apparently doesn’t behave like a damper). Claimed weight is 1,113 g with a 165 mm-long steerer (but without the compression plug or thru-axle), and retail price is US$1,200 / AU$2,034 / £1,200 / €TBC.

For the more weight-conscious, there’s the Invert SL, which offers 30 mm of travel and ditches the Climb Switch to shed a few grams. Claimed weight is just 990 g under the same conditions, and retail price is US$1,100 / AU$1,848 / £1,100 / €TBC.

Either of those prices are a fair bit higher than what you’d pay for a gravel suspension fork from RockShox or Fox, but again, Cane Creek’s new offering is a good chunk lighter. Cane Creek is also including its rather nice Ancora expansion plug, as well as a new 52 mm-diameter lower headset bearing just in case the one currently on your bike doesn’t have the 36° taper required for the integrated crown race.

In terms of compatibility, there are no real surprises here. Cane Creek says the Invert should work on pretty much any head tube designed around a 1 1/8-to-1 1/2” steerer. The 40 mm-travel Invert CS sports a 435 mm axle-to-crown length and 45 mm rake, and the 30 mm-travel Invert SL measures 425 mm-long with a 44 mm rake. Both should make for a pretty seamless transition handling-wise on bikes that are equipped with suspension-corrected forks of similar length. The lower legs are designed to work with 180 or 160 mm-diameter rotors and standard flat-mount disc-brake calipers, but with the shorter adapter plate normally used on rear flat-mount brakes since there isn’t enough room for the usual one.

Cane Creek is only offering the Invert with an all-black finish initially, but if its Helm 2 mountain bike suspension fork is anything to go by, I’d wager it won’t be long before we see some limited-edition colors. I’d also guess we’ll start seeing these on custom bikes with painted-to-match carbon upper assemblies sooner than later.

On the trail

I was originally supposed to get the full scoop on Invert at Cane Creek’s headquarters in Fletcher, North Carolina, but a scheduling snafu resulted in the company’s product marketing manager and design engineer coming to me with their bikes and an extra pre-production Invert CS in tow. While I lost out on some of the nitty-gritty development backstory I’d hoped for, the change still turned out to be an upside as while I was still only able to ride that sample for a couple of days, it was now not only on roads and trails that I knew really well, but also my own bike so I could gather particularly well-informed early impressions.

The main purposes of any bicycle suspension are always control and comfort, and the Invert CS I rode certainly provided the latter in spades. I ran my test sample in stock form with one volume spacer inside the main air chamber and a bit lower than the recommended 95% body weight in air pressure.

The Invert CS felt impressively active on smaller chatter and was excellent on washboard, smoothing things out so well that I basically stopped thinking about either one – just hold on as you normally would and go. In fact, it’s pretty easy to forget about the fork entirely, and instead focus more on going faster and having more fun. There was a touch of initial stiction but I didn’t find it at all bothersome. In fact, I actually kind of liked how it limited bounciness a bit when riding out of the saddle. There was so little pedal-induced bobbing or unwanted motion in general that I only resorted to using the Climb Switch on tarmac, enough that I found myself wondering if I might prefer the SL.

Further nudging me in that direction was the Climb Switch itself as I not only found it largely unnecessary for the gravel riding I do (likely a minority opinion, in fairness), but it also wasn’t the most pleasant to use. It worked as intended, dramatically firming things up while still leaving some movement on tap if you really nail something unexpectedly. It’s also a nice, big target on top of the crown and easy to find while riding. However, it also requires a very firm push to actuate. The tactile feedback is excellent, but it just requires enough force that I almost found it disruptive.

The second day’s ride included a fair bit of underbiking, and I certainly had some doubts about how well an undamped fork like the Invert CS would deal with more demanding situations that had bigger impacts and more complex terrain. However, it handled those much better than I’d expected. It didn’t feel like I was on a pogo stick, and it did a good job of keeping the front tire stuck to the ground in general.

I only bottomed the fork out once or twice, but when it did happen, I was greeted with a less-than-pleasant clunk instead of a gentler landing since Cane Creek uses a hard plastic ring instead of the more typical rubber pad to prevent metal-on-metal contact – apparently a consequence of the Invert’s internal design. There unfortunately wasn’t time to experiment with volume spacers during the trip, but my hunch is that I would’ve liked one more to ramp up the spring rate a bit more toward the end of the travel.

At least in those conditions, I still wonder what the Invert CS would have felt like with some sort of damper. It’s highly active and sensitive, and provides a super smooth ride in most conditions that you’d typically find yourself riding a gravel bike. However, it’s still a little more frenetic-feeling in that environment as compared to the somewhat more planted feel of the Fox 32 TC or RockShox Rudy. To be fair, I don’t think that sort of riding was quite what Cane Creek had in mind when designing the Invert, and it really does feel more at home on more “typical” gravel terrain.

I had no qualms whatsoever about the Cane Creek’s innovative structure, though. I’m no stranger to upside-down forks – I was a diehard Maverick DUC32 devotee back in the early 2000s – but single-crown versions never caught on, largely because they either lacked torsional stiffness required for precise handling or ended up too heavy. The Invert suffers from neither of those issues as the massive carbon fiber upper structure is both plenty rigid – both fore-aft and through hard corners – and impressively light, the lower legs are relatively stout with 30 mm diameters, and there’s a lot of separation between the upper and lower bushings. I’m not sure how well such an arrangement would work in a longer-travel application, but it seems to do the trick just fine here.

Why bother?

OK, back to that question I alluded to earlier about why someone might even want to bother with proper suspension on a gravel bike. Short answer? It depends.

I’ve mentioned more than a handful of times how gravel bikes – and gravel riding – exist on a spectrum, with one end comprising terrain and riding that’s not all that far removed from tarmac, and the other bumping up against (and maybe even overlapping with) cross-country mountain bikes. Ultimately, your opinions on gravel suspension will probably depend heavily on where you sit on that spectrum, but there are tangible benefits wherever you find yourself.

I’ve got two drop-bar bikes that I regularly ride on unpaved terrain. One is more of an all-road bike with lightly treaded 35 mm-wide tires. The other is a more “proper” gravel bike with tires that typically hover around 40-45 mm. For the former, I often run a suspension stem with 20 mm of travel as it incurs a very minor weight penalty (less than 100 g), and with the way I have it tuned, it helps maintain contact with the ground on stuff like washboard while still providing a bit of extra insurance if I decide to push things a little further.

But for the latter, I often find myself wanting a little more than what a suspension stem can offer, and a short-travel fork makes a lot of sense – at least for me. The added weight doesn’t bother me for the sort of exploratory solo riding I tend to do with that bike, and the fork allows me to have a lot of fun on the sort of terrain I’d otherwise find boring on a proper XC bike.

Am I saying suspension is for everyone? Nope, not at all. But I am saying that different riders will have different wants and needs, and neither side should be disparaging the other for choosing whatever works better for them.

A good first taste, but I’d like another bite, please

I bid the Cane Creek folks adieu with very good first impressions of the new Invert. It legitimately offers improved comfort and control, and certainly expands the fun factor of a good gravel bike. It’s also helps that it’s a lot lighter than most of the competition and less visually obtrusive.

I’d still love to get some more time on a production unit to answer some lingering questions, though. As mentioned earlier, I didn’t have a chance to try out different spring rate settings, and I wonder if one more volume spacer might get me the bottom-out resistance I’d prefer for the type of riding I typically do. That question will also be influenced by the fact that Cane Creek apparently already resized the lower bushings on production units to reduce stiction as compared to the pre-production sample I rode. Maybe I’d want two more spacers at that point? Or maybe my preference would stray back toward the slightly longer-travel Invert CS instead of the lighter and more pared-down SL?

I’ll hopefully get to answer those questions sooner than later, but I can at least say I’m sufficiently encouraged by the Invert that I actually want to find the answers. Stay tuned for more.

More information can be found at www.canecreek.com.

An update from Cane Creek product marketing manager Will Hart regarding questions people have raised about potential damage to the stanchions from rocks and trail debris:

“It is certainly possible, but stanchions still get scratched on conventional suspension forks all the time. The surface area on Invert is much smaller, and the terrain is generally less dangerous than a gnarly mtb trail (at least on paper). One could argue that small chunks of rocks and gravel are likely to get kicked up, especially when riding in groups, and I wouldn’t argue with that. However, we’ve been riding these forks for several seasons through the development process and not one of us has had any sort of issue here. We haven’t had a single instance of scratching or damage from kicked up gravel.“

What did you think of this story?