When it comes to modern cross country racing, there is no bike model longer-lived than Cannondale’s Scalpel full suspension. Way back in 2002, it was a revolutionary short-travel option, with a flexible carbon fibre chainstay and the brand’s iconic one-sided Lefty fork up front.

Fast forward to today and the latest generation of the Scalpel, introduced in 2024, continues to stick to those racing roots. It’s even had quite the debut season, with a World Championship win, a bronze medal at Olympics (both via Alan Hatherly), two marathon World Championships (courtesy of Simon Andreassen and Mona Mitterwallner) and several World Cup wins in XCO and short-track. However, as those marathon wins show, like many other modern cross country (XC) race bikes, the Scalpel offers a bump in suspension travel and ever-more progressive geometry that makes it an interesting choice for more than just zip-tieing on a number plate.

Better yet, Cannondale has said farewell to its proprietary offset rear wheel and crankset, and many models now come equipped with a regular fork, too. The Scalpel continues with a familiar silhouette that many others have converged on, but as with every bike, there’s nuance in the details.

I’ve spent well over six months testing the new Cannondale Scalpel 2 (sorry it’s been so long, Cannondale), a third-tier model with a surprisingly well-thought and race-ready specification. It’s been a long enough review period to confidently confirm the good, the bad, and the compromises to be aware of in owning this well-rounded XC bike.

Lows: Integrated cable routing causes wear points, no remote lockouts for the racers (regional-specific issue, and also a positive for me), rear linkage creak on my sample, flexy front wheel, incorrect dropper remote placement, no internal frame storage, play in dropper, stock grips.

Price: US$6,500 / AU$8,600 / €6,800

Dissecting the details

Following the history of the Scalpel gives a glimpse into the continued progression of cross-country racing. Today, many of the bikes being raced at the pointy end look a whole lot like trail bikes of a few years ago, and that makes the category increasingly attractive not only for those who race, but those who merely want a mountain bike that’s still enjoyable to pedal.

While it may look similar to its predecessor, the new Scalpel offers some welcomed changes. The previous Scalpel offered 100 mm of travel in the race version, and 120 mm in the “SE” version; by contrast, the new Scalpel settles on a consistent 120/120mm front and rear travel through the whole range. Plus, each bike comes stock with 29 x 2.4in tyres, the official maximum for the frame (6 mm of clearance measured at the tightest spot).

Cannondale offers this travel with linkage-driven suspension design built around a lighter and hardware-less “FlexPivot” at the rear dropout. Most cross-country bikes on the market today play on a similar concept, but the American brand’s more extreme approach is one of the few examples where you can visually understand where and how it flexes in place of a more traditional pivot point, and according to Cannondale, it emulates a four-bar Horst design. It’s a design that also makes figuring out the bike’s kinematic figures a little more confusing.

Similar to the likes of the Specialized Epic and a number of others, the off-the-shelf rear shock (190 x 45 mm) is driven via a small rocker link that provides space for two water bottles within the main triangle (in all sizes). In an effort to improve insertion depth for longer dropper posts, Cannondale offset the seat tube bottle mounts forward, a function-over-form design detail that makes the new Scalpel easy to spot over the version before it. Unlike some competitor bikes, the new Scalpel offers no internal frame storage.

Further striking frame details are seen in the surprisingly wide and flat top tube (65.5 mm at its widest) that is scalloped for the rear shock to sit into. Meanwhile up, front is a large, but clean head tube that houses the housings. Yep, the new Scalpel routes the rear brake hose, and if applicable, dropper post cable, rear remote lockout cable, and rear derailleur housing through the headset. There is some fancy funneling within for easier assembly plus some protections for the steerer tube, but it’s still vastly more complicated for questionable benefit. More on this later.

The rear shock is nestled into the top tube. It's an impressive hollow structure when viewed from below and with the shock removed (right).

Thankfully that headset routing is the only polarising design decision of note, with Cannondale having now walked away from many proprietary concepts that previously gave me pause in recommending the Scalpel. Indeed the company’s Asymmetric Integration (Ai), which offsets the rear wheel and crankset, is now in design jail, replaced with a regular Boost rear wheel (148 x 12 mm) and crank chainline (55 mm). Better yet, the weird 83 mm-wide PF30 bottom bracket has also been locked away, with Cannondale reverting to a regular English-threaded bottom bracket. I’m stoked to see these changes, but am not yet ready to forgive Cannondale after hearing multiple reports of difficulty in finding aftermarket replacement Ai cranksets – if you’re going to do proprietary nonsense, then support it appropriately. Oops, I’m now ranting about something somewhat unrelated; moving on.

Of course, the new Scalpel features a UDH (the equipped SRAM Transmission derailleur wouldn’t be possible without it). The dropper is a regular 31.6 mm diameter held with a standard external clamp. There’s a neat little chain guide integrated with the main pivot bolt. The frame can officially accept up to a 36T chainring. And not being locked into electronic everything will certainly please many – although just be warned the exit hole for the derailleur housing is in a compromised position due to the flex pivot (not relevant to the AXS-equipped model tested).

A well-designed and minimalist chain guide is supplied. Meanwhile, the regular English threaded bottom bracket is a welcome sight on a bike that's sure to be covered in grit.

The frame is certainly light, too. Cannondale claims its flagship Lab71 frame weighs just 1,770 grams in a size medium, painted, and with frame hardware (though no rear shock). As tested, the second-tier frame lay-up is claimed to weigh 1,950 grams (again, no rear shock). On my scales, my medium-sample frame measured an actual 2,160 grams, including the RockShox SIDLuxe Select+ rear shock (includes rubber frame protection, chain guide, and frame hardware. The headset, seat clamp and thru-axle were not included). Those weights are certainly competitive with many others in the category but are not the very lightest; for example, the top-tier Yeti ASR is claimed to be almost 200 g lighter.

In the numbers

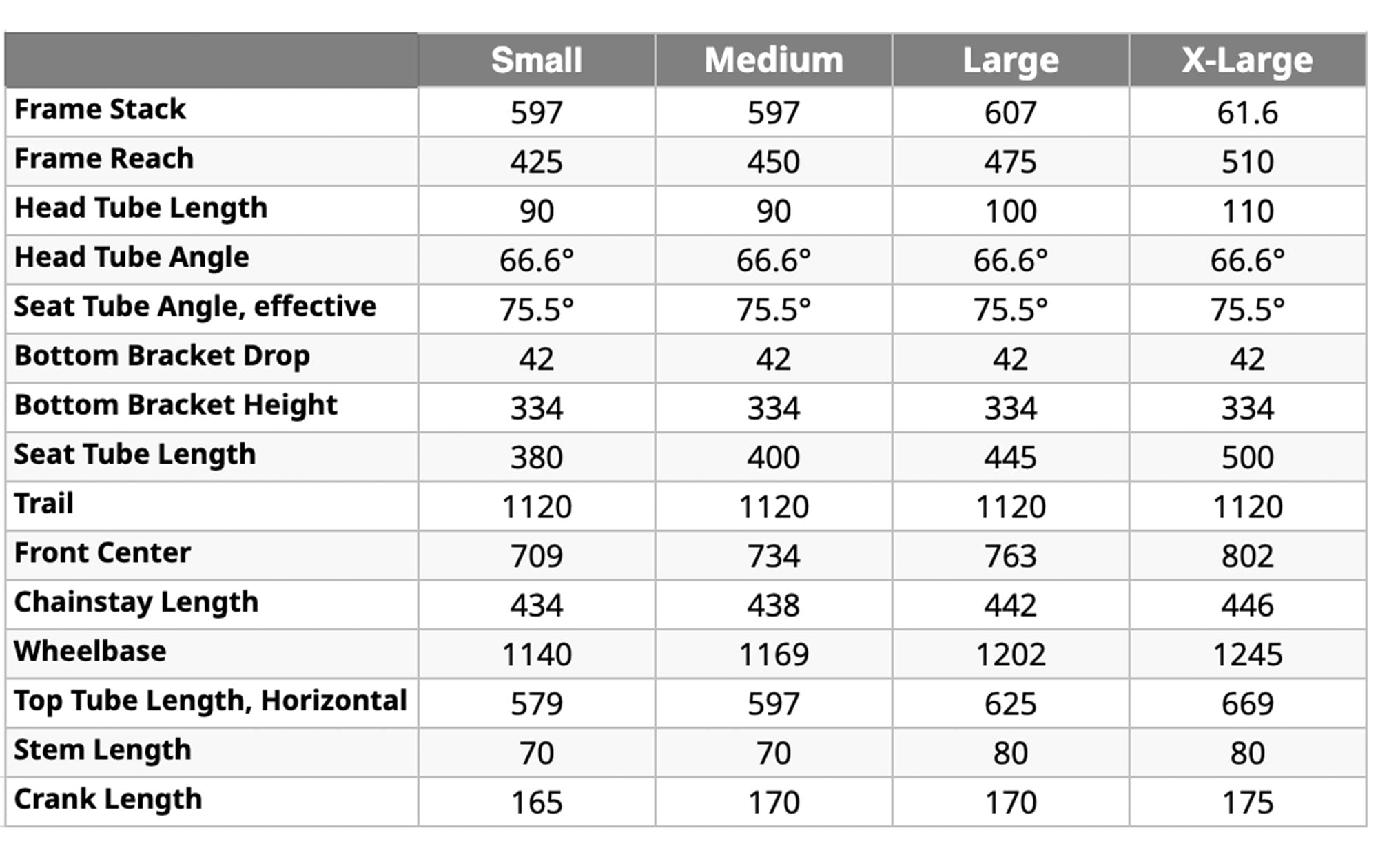

Many of the latest cross-country bikes are hovering around similar geometry figures, and while not necessarily a bad thing, the Scalpel isn’t the most progressive of the lot. With only four sizes on offer, each one features a 66.6° head angle (figure verified and measured without sag), while the effective seat angle is 75.5°. By comparison, the latest Specialized Epic 8 sits approximately a degree slacker in the head angle, while the Yeti ASR is an almost exact match to the Scalpel.

An emerging trend in enduro and trail mountain bikes is size-specific chainstay lengths that grow in relation to front centre lengths with the goal of improving weight distribution. It’s a costly endeavour, and rather than having one rear triangle for all frame sizes, moulds need to be made for each length. Cannondale clearly believes it offers benefits as each frame has a unique chainstay length, starting at 434 mm in the small, and growing in 4 mm increments up to 446 mm in the extra-large.

As has become common for the category, reach numbers are extended in relation to shortened length stems. My medium tester came stock with a 70 mm stem (as does the small), while the large and extra-large sizes ship with a 80 mm length stem. The reach numbers are modern, but there are longer bikes on the market for a given size that also feature shorter stems (such as the new Specialized Epic 8 and Canyon Lux).

A region-specific range

Cannondale has one of the more confusing ranges, with the build specification notably varying between North America and Europe. If you ever needed proof that the European and North American markets often want different things in bikes, this is a prime example.

Broadly speaking, the EU versions of the Scalpel tend to feature Cannondale’s unique Lefty fork in many more models, and all offer RockShox SID two-position rear suspension controlled by a TwistLoc handlebar remote. By contrast, in North America, the top-tier Lab71 model (US$14,000 / €13,000 / £10,000) features a Lefty and remote lockouts, while every other model features a fork from RockShox or Fox and no remote lockouts.

Don’t be scared off by that Lab71 version as prices start from US$4,000 / €4,300 / £3,950 with the Scalpel 4. This one features the identical frame to the Scalpel 1, 2, and 3, and shares a mould with that Lab71 version.

Given all the regional differences I won’t bore you with a range run-through, so instead, let’s look at the third-tier Scalpel 2, the exact model of this review. Region-dependent, the Scalpel 2 is available in three subtly different versions. There’s one with RockShox SID Select+ two-position suspension controlled by a TwistLoc remote (€6,800). There’s one with the same remote lockout, but with a single-sided Lefty up front (€7,500 / £6,750). And there’s the North American model as tested with RockShox SID Select+ two-position suspension with no remote lockouts (US$6,500). Adding to all of those options are choices in paint. In addition to the tested black and grey, the Scalpel 2 is available in a nice blue and red combo.

As tested, the North American version keeps things simpler without remote-controlled lockouts. And as you'll read, I rarely missed the feature on this bike.

While I’ll admit to having initially been disappointed to have pulled my Scalpel test sample from the box and find the fork had two legs, the more regular specification helps to keep the price in check. And Lefty or not, there’s a number of smart decisions to be found that led to a competitive 11.38 kg weight given the price point (weight is with 60 Ml of tubeless tyre sealant in each tyre, but without pedals or bottle cages, size medium).

A sharp spec

It’s been a few years of SRAM dominance in the upper-end mountain bike market, and that sure applies to much of the Scalpel range. In addition to the RockShox SID Select+ fork (35 mm stanchions) and rear shock without remote lockouts (I’ll return to this), the tested Scalpel 2 features a full SRAM GX Eagle Transmission group, offering a 34T chainring and the 10-52T cassette range.

I’ve previously raved about SRAM’s Transmission shifting and the GX stuff is no different. Short of getting a nasty stick in the derailleur cage, there isn’t much to worry about with the system and it’s one I’ve personally smashed into a rock slab (a stupid crash on the e-bike) without the slightest change to how it functions. It’s not a lightweight system, and some complain how slow it is to shift through multiple gears, but it sure functions great and allows you to safely shift like an absolute idiot off the start line.

The SRAMness continues with the four-piston SRAM Lever Bronze Stealth brakes, a newer model that keeps the hoses close to the handlebar. These are matched with thicker (and heavier) 2 mm HS2 rotors that are more trail-oriented: 180 mm for the front, and 160 mm at back. They’re OK, but are not nearly as powerful as I had expected given the four-piston calipers and rotors, plus the levers have a subtle rattle to them at times.

Did we do a good job with this story?