“The problem with cycling is that the TV doesn’t do it justice,” Mark Renshaw says.

One of the greatest leadout men in history is talking specifically about sprinting. Watching at home, we don’t see anywhere near enough. In real time, you cannot keep an eye on the final few kilometers of a modern finale, as the contenders surge, fall back, and move like coloured marbles firing down a tube.

If we’re lucky, helicopter replays will show us the last 1,000 meters from the air. Usually, by then, one team is in the box seat, a few of their men leading the arrowhead formation at warp speeds, with rivals bumping and barging in their wake.

But the sprint itself, a dozen seconds of four-figure wattage and thrashing limbs, is just the final chapter of a tome. Behind the sprinter raising arms in victory, there is a retinue of canny, powerful domestiques – the leadout train, a mainstay of the sport for the last 30-odd years.

Anyone with serious designs on winning a race who goes into a finale without such help is asking for trouble. It’s like running out into a monsoon without an umbrella. Good luck not getting wet, pal.

Together, the two Marks, Renshaw and Cavendish, were the finishers in the gold standard for 21st century leadouts, the HTC-High Road express. In a discipline riddled with variables and uncertainty, they would perennially come to the front, take control and made a Cavendish bunch sprint victory a borderline sure thing. At HTC’s zenith, from 2009 through its final season in 2011, he took 24 Grand Tour stage wins.

Compared to the smooth-running trains of HTC, contemporary sprints appear messier and more hard-fought, with more teams and wannabe winners in the mix. Where HTC drove the front for kilometers at the time, today several trains fight for control of the bunch and the best lines, changing leads constantly.

What changed; how did we go from the seeming orderliness of the HTC train to the pell-mell tumble of today? It might seem counterintuitive to call today’s sprints an evolution rather than a regression to the chaotic origins of the leadout. But that’s exactly what they are: a step forward rather than back.

Bullet trains

Still, it’s hard not to look back at the precision of the HTC train as anything other than the apex of the leadout era. Renshaw talks me through what they’d do, starting with committing a couple of riders to ride tempo and keep a leash on the day’s break.

Ten kilometers to go was often the point HTC’s duo of day-long chasers would be relieved of their thankless duty and hand over to the leadout train, a phalanx of men in distinctive white-and-yellow hitting the front. Leading the pack meant they could pick their lines and decide which side of the road to go, unencumbered by rivals.

It’s here we note a couple of things that set HTC apart from modern-day teams. First, it was an era in which nine men lined up in a Grand Tour team rather than the contemporary eight. It’s also worth noting that HTC was almost entirely focused on stage wins, chiefly sprints; at times, the team dedicated six riders to the last 15 minutes of the race.

Over those finely tuned final 10 kilometers, every man would ride for slightly shorter amounts of time, requiring slightly greater power. So of course it mattered a lot who those riders were. It was often young diesel Tony Martin – who would ultimately win four World Time Trial Championships between 2011 and 2016 – getting them up to speed, driving the pace too high for late attacks. Then, veteran domestique George Hincapie was man five, followed by road captain Bernhard Eisel in the engine room, calling the shots. He would swing off for Matt Goss or Edvald Boasson Hagen – sprinters who won plenty in their own right – in front of Renshaw and finally Cavendish. Aside from all that freakish individual power, why did it work so well?

“Clear goals. The guys knew what the job was, so we all committed to it,” Renshaw says. “Obviously, we had one of the quickest guys, so confidence in getting the victory was there. And every time we lined up and got a victory, it lifted us further for the next one. I think having confidence in the team is the biggest thing in leadouts.” In the team’s most successful season, 2009, its riders won an astounding 86 races, 50 of them bunch sprints from Cavendish, Boassen Hagen, Andre Greipel, and Greg Henderson.

Bunch sprinting is about pre-empting so the sprinter can be at the right place at the right time. Quiet and calculating, Renshaw could write a thesis about how a twitch on one side of the bunch with 2 km to go can affect movement on the other side, like a ripple in one part of an ocean disrupting the water farther away. At his best, the Australian could also manoeuvre other riders to make room for Cavendish to go into gaps.

Their sustained success also meant that, over time, spaces opened for them because everybody was looking for their wheel. A sprint is never straightforward; Cavendish and his cohorts often just made the chaotic look borderline routine.

Steam engine origins

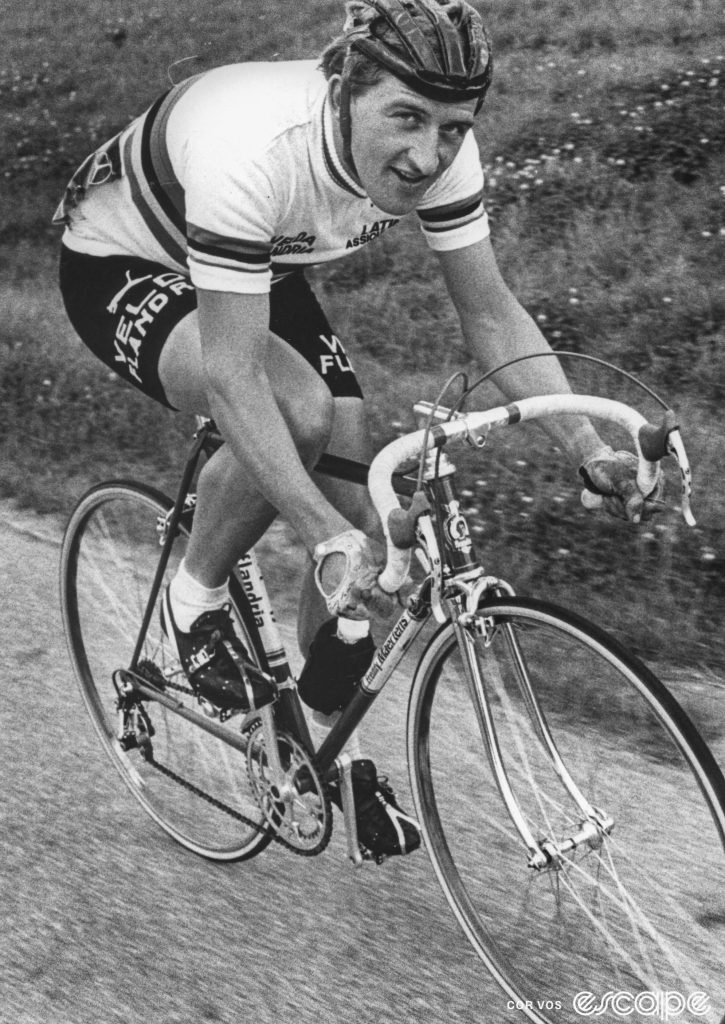

The leadout has become a lot more structured and methodical over the years. It’s impossible to pinpoint the precise moment when concerted trains began; Rik Van Looy had several teammates in his “Red Guard” in the Sixties. (There’s pleasing, grainy footage showing his teammate Ludo Janssens leading out The Emperor to victory in a hectic velodrome sprint into Bordeaux in the 1963 Tour de France)

But back then, it was usually a two-man band; in the 1970s, the mercurial Freddy Maertens could rely on Marc Demeyer to help him in the race’s dying moments. (Speaking of confidence begetting streaks: in the 1977 Vuelta España, Maertens won an almost comical 13 stages – only a few of them sprints – and the overall.) Winning a sprint required a lot of barging, nerve, and using’s one’s wits to jump onto faster passing wheels.

Neil Stephens, riding for ONCE sprinter Laurent Jalabert, remembers it being a lot more ad hoc. “We’d basically sort out the leadout as we’re going into the finish: we’d talk amongst ourselves, see who was going the best,” the Bahrain Victorious sports director says now. “We didn’t have race radios. Obviously, we had a bit of an idea what would happen in the finish if we got there, but we had to make a lot of the decisions ourselves.”

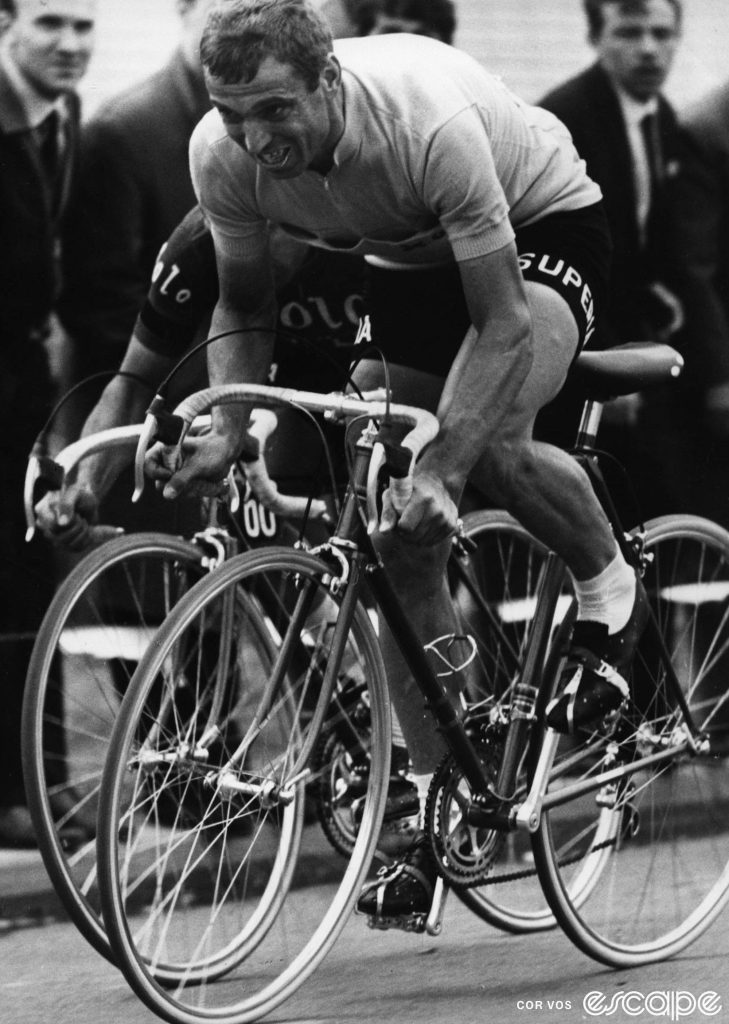

Into the late 1980s, Superconfex changed the game for Jean-Paul van Poppel, who was speedy but ill at ease freelancing in the finale. So the team built a leadout of powerful Dutch flahutes: Gerrit Solleveld, Frans Maassen, and Edwig van Hooydonck would take charge and chase down breakaways late in the race, while Jelle Nijdam was last man. “They were one of the earliest teams to ride that way,” Sean Kelly told Procycling in 2018. “Up to then, sprints could be very scrappy. You might have had one or at most two leadout men for a sprinter, but they wouldn’t move until the end of the race.”

Superconfex’s approach for Van Poppel was effective: in 1988, the Dutchman won four Tour stages. Other teams noticed, and began to assemble their own multi-rider leadouts, often built around star sprinters.

In the 90s, Mario Cipollini and his “red train” at Italian squad Saeco further honed the art, with even more structure and men riding for him. His rival, Erik Zabel, clad in the magenta-black of Telekom, developed his own version, later purloining Cipollini’s leadout men Giovanni Lombardi and Gianmatteo Fagnini. From there, it was a fixture; the race between rival trains was on.

Locomotive and engineer

Whatever the era or number of helpers at hand, when it comes to a sprint, power is nothing without being in the right place at the right time. And that’s all about the last man (or woman).

A leadout has to be calm and think for two. When it works well, it can be a case of a Batman and Robin-esque duo immortalised: think Cipollini and Lombardi, Jasper Philipsen and Mathieu van der Poel, or Cavendish and Renshaw. (Their mutual faith has extended post-career; Renshaw, who piloted Cavendish to half of his record-tying 34 Tour stage wins, is now Cavendish’s sports director at Astana Qazaqstan to help him finish his quest for the outright record.)

Incidentally, the physical difference between a sprinter and his last man is often small; leadout men are often fair sprinters themselves. It’s a matter of higher peak power, aerodynamics, and the ability to dig exceptionally deep in the final 10 seconds, going beyond the limit to a place many riders can’t quite reach.

“I never had that 10-second real, peak power where I could just push that little bit more to take the win,” Renshaw says. “I think it probably comes way, way back to when I was a track rider and doing so much training for the kilo time trial, for one minute. I think that carried on over to my pro career.”

Ungodly wattage only goes so far, though. Cavendish rarely gets over 1,400 watts but he can average close to that for fifteen seconds, whereas a rival like André Greipel could push 2,000 but would dip faster. (Cavendish’s signature low crouch is also thought to make him more aerodynamic than some sprinters’ positions.)

Renshaw recalls leading out Matt Goss at the Tour Down Under, hitting 1,000 watts for a minute. “And he didn’t win the stage,” he adds. In bunch sprints, you use your brain as much as brawn; that’s another reason why they are so fascinating. From one day to the next, the dynamic can change as quickly as a solar-powered kaleidoscope in the Atacama desert.

For all sprinters, victory is the goal and the magic elixir. “Nothing makes a difference more than that,” says Soudal-Quick Step director Tom Steels, a nine-time Tour stage winner and key advisor for his team’s long line of triumphant speedsters. It means self-assurance and the licence to act instinctively without overthinking in the next showdown. “The bunch sprint is a very hostile environment. With doubts and aggression, you just get lost,” Steels says.

“It’s like a boxer in a ring who wants to win but loses his momentum, lets his guard down and gets hit. It’s a bit the same in a sprint: you have to stay relaxed and keep that ability to think about where you are and keep that confidence. But it’s easier said than done.”

Fast tracks

As recently as the HTC days, sprint trains were mostly focused on the final 10 or so kilometers. Nowadays, the battle for position between teams on flat Grand Tour stages can begin as early as 100 kilometers from the finish, and it’s a lot fiercer than it appears.

“What people see on TV doesn’t resonate with the feeling within the group,” Renshaw says. “When we see the peloton so tightly-packed and in a straight line across the front, it looks like it’s really easy. But in my final few Tour de France participations [in 2018 and 2019], there were fights where it would take 15 to 20 kilometers to move just 15 rows in front.”

As the race heads towards the finish, a team’s challenge is to move through gaps together to get into the first few lines of the peloton. It’s like a train of carriages going through a tunnel which is expanding and contracting in width; Renshaw likens the task to riding a tandem.

Once finally at the front, it’s about executing the plan. No blueprint on a flat stage is the same because, like a snowflake, no sprint finale is the same. A UAE Tour run-in on a four-lane road with few corners has very different characteristics to a Paris-Nice or Tour de France finish on the road furniture-littered outskirts of a provincial town on a finish straight just six meters wide.

“Nowadays, if it’s not a technical course, it’s very difficult to dominate the sprint or to get a real leadout for it,” Steels says. “You have to look at the course to see if there is a possibility and to see where you have to be united. Especially in a Grand Tour, you have to wait that last 10 km, when the speed really goes up, when the GC guys start to lose their [support] riders, to get some space on the road to try and get organized.”

He believes the course has to help for one team’s leadout to dominate. For example, a run-in conducive to a well-oiled train needs disruption of speed and direction. It would include a village before with some technical corners to help a team stay in the front of the bunch. A few roundabouts or bits of traffic furniture for a sprint train to find each other and line it out help. A straight, spacious boulevard of 10 kilometers is a no-go for that.

Once the race is on, Steels believes that having a team take responsibility and chase down the day’s breakaway is a boon.

“It sounds crazy, but often that five per cent more [commitment] can make the difference between winning and losing,” he says. “Because if the team worked all day, the sprinter puts himself under a bit more pressure to win. You want to win, but you know you cannot lose – if they pull five times, you have to win one or two times, or you lose the team’s confidence.”

It’s not easy for a team to pick a point where to start their final push. There’s a need for flexibility, with no guarantee that the full, intended complement can make it to the front. Nowadays, the leadout has to be shortened.

“Before, you had a full team and they started to go. If they got space, they just started to ride,” Steels says. “Now, it’s often one or two guys, sticking together. You try to pick a point for more riders to come, but you’re never sure if that can happen.”

Over the years, Soudal-Quick Step have gotten the best from a variety of sprinters, such as Marcel Kittel, Elia Viviani, Mark Cavendish, Fernando Gaviria, Fabio Jakobsen, and now Tim Merlier, with Paul Magnier and Luke Lamperti the likely next generation.

However, they also owe a lot to the men leading them for the success even if those riders don’t always play a part in the final. “It’s a lot to do with the midfield you have, because they have to prepare the sprinter,” Steels says. It helps when there’s former World Champion Julian Alaphilippe, Yves Lampaert, and Tour of Flanders winner Kasper Asgreen shepherding them from the wind.

Steels notes that if there is a descent near the finish, sometimes those helpers will be turning a 56, even 58-tooth chainring to ensure they have the horsepower to keep their fast man in position.

Ultimately, the perfect leadout has not changed dramatically since Renshaw and Cavendish’s heyday; it’s just that no team can now routinely rely on five riders bossing it.

The first rider is keeping position and the others safe, out of the wind. Then, ideally, there are three leadout men under the flamme rouge: one making it to 800 metres, the penultimate rider swinging off with 500 left then the last man peeling away with 200 metres to go, terrain and wind depending. The goal is to leave the designated sprinter in front, slingshotted at high speed, with the shortest amount of distance to cover and the optimal amount of energy saved.

“You have to really time it perfectly, so the guy in the wheel of your sprinter is also already suffering,” Steels adds, which of course is not so easy. “For a straight road, you need more men to keep the bunch’s arrowhead shape and speed high, otherwise a sprinter can come from the second or third line and have less wind resistance.”

“It has a lot to do with the strength and confidence of the last man,” he adds. Steels brings up Michael Mørkøv (now an Astana Qazaqstan rider) as a paragon of a modern leadout man, someone who could do it in a train or by himself, and possessed of immense intelligence and an intuition for developing gaps.

“He probably learned from the track, to see things happening before they happened, which is a very good quality for a leadout,” Steels says. “And then you build up trust with your sprinter … because he has to follow you almost blindly.”

Modern maglevs

The challenge of winning a modern sprint is in some ways the same as always: finding infinitesimal gains, timing, smart preparation, quick thinking, power, strong midfielders or keeping your leadout train in front. But sprinters today also must adjust to faster average speeds and harder routes, especially in Grand Tours. No good being a fast man who can’t make it to the finish in contention.

Bahrain Victorious’ Phil Bauhaus is one of the best in the game, with several top-three stage finishes in last year’s Tour de France and a Tour Down Under stage to his name, among over 20 career wins. But he knows that to take the next step his top-end sprint isn’t enough.

“I also need to improve on the endurance and the longer efforts,” Bauhaus says. “The profiles get harder, there’s more and more metres of climbing in every Grand Tour. And every sprint stage, you have 1,500 to 2,000 metres of climbing before a sprint. So I need good endurance to even come to the sprint.”

At last year’s Tour de France, Bauhaus finished third on a day with over 1,800 metres of climbing. Opportunities are arguably fewer, too; in the 2020s so far, there have been an average of six sprints for victory at the sport’s most prestigious race, compared to eight (well, 7.6) in the decade before.

Recovery is also a key factor. We don’t see the sprinters on TV in the Alps or Pyrenees, but those mountain-stuffed days ebb their physical and mental reserves, and those of their teammates. There’s a world of difference between a stressful, tiring calvary to sneak under the time limit by seconds and a more comfortable day of suffering. It could be taken for granted that Jasper Philipsen, this era’s preeminent fast man, is not just a rapid, smart finisher on the flat but someone who regularly finishes ahead of rivals’ gruppettos in the mountains too.

Another thing that has changed is the science of preparation. Nowadays, the job starts weeks or even months before. Every team studies the parcours. Team managers deliver a few key points in the team bus on the morning of a sprint stage – no point overloading riders’ brains – and pick through video footage from a scout who has personally been over the day’s run-in. It’s moved on from sticking the orange man in the road on Google Street View, which HTC were one of the first teams to do.

Decisions are taken on wind-appropriate wheels, tyre pressure, nutrition and clothing, all minor areas for potential improvement. “In our days, if you put on a skinsuit, they would laugh at you the whole race,” Steels says. “Now, if you don’t have one, you’ve already almost lost.”

So, what’s the next area of improvement in an increasingly-refined discipline? Looking to the future, Bahrain director Stephens thinks that in a few years’ time, every team will have several aerodynamicists at a race, working on optimising positions for fast men. (In fact, some teams already do this for other disciplines like team time trials, using power data and aerodynamic modeling to try to optimise the order and role of each rider in the line.)

Runaway speed

So, who would be a modern sprinter, charged with finishing this complex puzzle off? To Bauhaus, a pro since 2015, the answer anymore is everyone. Up until a few years ago, squads like Movistar and Astana were focused on climbers and GC results.

“They didn’t even have a sprinter. Or if they did, they didn’t have a leadout,” the German says. “Now, you can see that basically every team has a sprinter in their line-up. And every team is trying to make the best possible leadout they can. There’s more and more riders involved in the final and many more sprinters.”

“My personal feeling is that the Covid crisis had a part in this,” Bauhaus adds. “Before [Covid], every team was a bit more chilled and didn’t feel the pressure so much. Then, with Covid-19 coming, every team saw how vulnerable they are, with sponsors or in general. Then with this relegation [system], every team needs points.

“The general level of all riders is high that there’s no cyclist in the pro peloton who isn’t good or in condition, so there’s nothing to give away. Even if you score five points that day, it’s better than nothing. So everyone really tries to get some results each day.”

Bauhaus believes it’s not impossible to win without a leadout, but practically necessary to have one nowadays. “Also mentally, it’s always much better to know you have teammates that are backing you up,” he adds. “In my career, I won 20 races and I think it would be much less without their support and without leadouts. It’s super important, in my opinion.

“I’ve had really good results without leadouts, when I didn’t have teammates anymore or races like the Volta a Catalunya, when there were just climbers in the team. But at the end, every sprinter wants to have a leadout.”

Bahrain often appears in finales as one of the many vying for control of the bunch, but we don’t always see them for long. Like a lot of teams today, they can pop up briefly at the front then get washed over by a faster team like pebbles in a surging tide.

Bauhaus has his best friend Nikias Arndt as leadout man with two or three riders helping him per day, part of an annual – if constantly changing – core group of seven sprint support riders in the WorldTour team.

He believes the leadout essentials are timing and finding each other well. Arndt, who has experience of Argos-Shimano days going back to Marcel Kittel and Michael Matthews, makes the call. Momentum is everything: if they’re surging too early and running out of manpower, it’s a case of dropping Bauhaus off on a good wheel rather than blowing up and being left behind by other locomotives.

“Maybe if we make it a little better so I get a little bit longer support into the finale. Or also do the perfect leadout so they can deliver me really from the front and I can start my sprint from first position,” Bauhaus says, thinking of improvements for 2024.

When I ask him what he’ll look to change personally, he suggests he’s missing some more speed, the difference between first and second. Bauhaus has focused more on gym work and strength training this winter, tweaking his training to include a few more sprints and improve his kick.

“But my speed is already on a highlight. We are talking about not even a percent [gain], just a little bit,” he says.

A lot has changed since the leadout’s first heyday 30 years ago, that’s for sure. “You’d have a group of 10 guys in a bunch that could possibly be around the mark, three or four of those possibly getting a decent leadout,” says Stephens, Bauhaus’ director at Bahrain. “Someone would be off on their own and might get lucky, or push in and get a good result.”

“These days, in the Tour de France, the work the sixth, seventh, or eighth-best team in the sprints are doing is probably as good as the best team was five years ago. They’re all doing a great job and we’re pushing each other as far as that goes. It’s not as if we’re doing something extra: we have to do the maximum just to hang with the best.

“That’s the big difference. In the old days, you could be lucky going for a bunch sprint. Not these days. No-one’s lucky now.”

Did we do a good job with this story?