It's been most of a decade now since Emma Pooley retired from professional bike racing. She did so as a time trial world champion (2010), a winner of four Giro d'Italia stages, an Olympic silver medalist (Beijing 2008, ITT), and one of the most talented climbers of her generation.

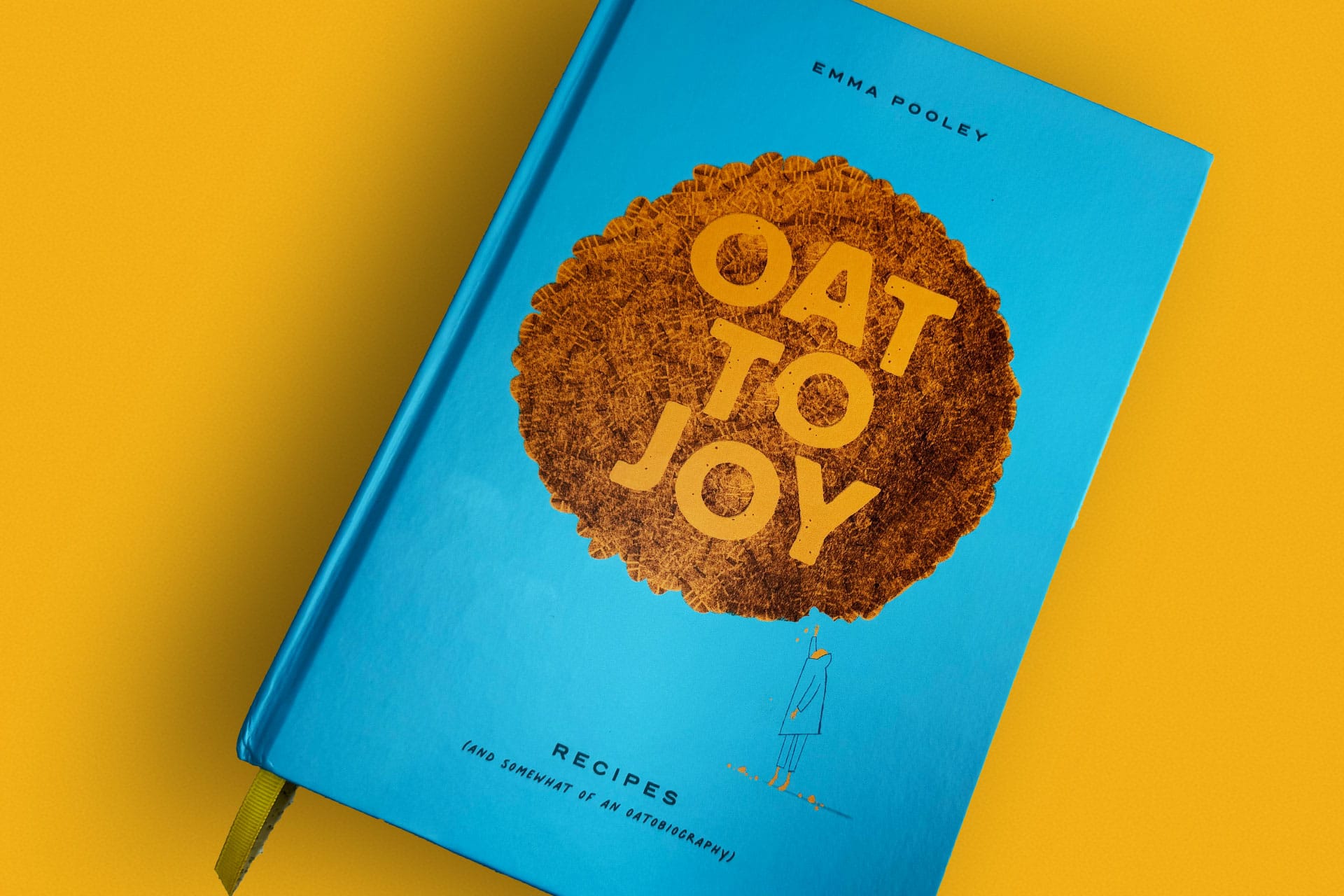

In the years since she has dabbled in other sports – triathlon, duathlon, and running – she's worked for GCN as a presenter, and most recently, she's worked as a geotechnical engineer in her adopted home of Switzerland. She's also been working on a book called Oat to Joy which she describes as "a recipe book for healthy, on-the-go, real food nutrition" that's "also a memoir, chronicling some of the most interesting times in my career as an athlete."

What you're about to read is an extract from Oat to Joy, complete with a companion recipe at the end. You can find out more about the book and how to get your copy at Emma Pooley's website.

You may have heard the controversial quote: "Nothing tastes as good as skinny feels." Beloved of anorexics, it’s been widely condemned for glamourising eating disorders.

Cycling suffers from a similar belief: "Nothing tastes as good as skinny rides." Except it’s not controversial at all. At every level of the sport there’s a common assumption that the thinner you are, the faster you’ll be.

It’s just as bad as the supermodel motto, but it mostly goes unchallenged. One reason is that aerobic exercise is often associated with the goal of weight loss. And yes, regular cycling can be a healthy part of lifestyle change for those who need it, but that doesn’t mean weight loss has to be the point of cycling for everyone. Weight loss isn’t even beneficial for everyone!

Another reason for the assumption that thinner equals faster is that old favourite, the correlation = causation fallacy. When people start cycling (or step up their training) they often lose weight and they also get stronger. For time-limited cyclists starting from a low baseline, simply riding more will make them stronger. Riding more might also make them lose a bit of weight. But those two things are both results of the increased training. It’s not just the weight loss that made them faster.

Basic mechanics tells us that in order to accelerate or go uphill, power-to-weight ratio is decisive (if one assumes that equipment weight as well as losses from aerodynamic drag, rolling resistance, and friction are equal between riders) so of course weight affects performance. However, most people would benefit more from working on the power side of the equation: ride more, structure your training, get stronger. That will make more of a difference than changing body mass. At the top level of elite cycling it’s different. Every factor is important when the margins between winning and losing are so small. And that’s why professional cycling sets such an unrealistic – and often unhealthy – example.

Lots of elite cyclists are very thin. Some naturally have a slim physique. The majority get there through restricted calorific intake and a huge training load. Their dedication to performance and self-discipline is impressive. The problem is it can go beyond performance, to an obsession with simply being thin. Why? Because of that almost-universal assumption: the thinner you are the faster you’ll be. It’s wrong, but it’s widely believed.

In pro cycling I encountered a level of ignorance on nutrition that was shocking, especially coming from people in positions of power. For example: the time when our DS shouted at me – in front of the whole team – because I ordered a hot chocolate. "It sets a bad example to the girls who are trying to lose weight," he told me. The same DS encouraged us to pour lots of olive oil over pasta and eat fatty meat every day. He didn’t even have a basic understanding of calorie density – he just associated chocolate with ‘unhealthy’.

But choc milk is not unhealthy; there’s good scientific evidence that it’s an excellent recovery drink. When I said so, he got even angrier and told me that as punishment I wouldn’t be allowed the usual recovery massage. I felt humiliated, unfairly treated, and upset. In fact I cried in that team meeting. Maybe my tears were partly from fatigue, because earlier that day we’d raced the GP Montreal World Cup. My team orders (from the same DS) had been to attack on the start line, which I did. I’d held off the chasing peloton for 110 km and ridden the entire race in a solo breakaway – a win that might be unique in cycling at that level. After an effort like that I needed to be consuming as many calories as possible, not restricting.

In any case, solo breakaway and victory or not, it was none of his business telling me what to eat. I was the athlete and it was my responsibility, not his, to be in form for the target races. I didn’t deserve to be treated like I couldn’t make sensible choices.

None of us did. We were elite cyclists. Every rider on the team had demonstrated their immense self-discipline just to reach the highest level of the pro sport. We were all different shapes and sizes and that was healthy and appropriate, because we were different kinds of riders. We were all capable of making dietary choices aligned with our own performance goals. And we were all more at risk of eating disorders than of being overweight for racing.

It can be helpful to feel supported in making healthy dietary choices. But this DS wasn’t supportive; he was controlling. He tried to remove athletes’ autonomy, rewarding with treats and punishing by withholding food. His dysfunctional approach to coaching and diet showed a lack of understanding of basic nutrition – and there were many more team directors and coaches like him.

Some of them were so stupid as to be quite funny. One team manager wouldn’t let us eat the soft inner part of the loaf of bread because he thought it would make ‘his’ riders fat. But the outer crust was fine – as if that somehow had a different calorific composition. Less funny though: the same manager would ban certain riders from eating at all on training rides. He also based team selection for the Giro on how defined our calf muscles looked.

Most Italian teams insisted riders eat pasta for breakfast – the carbohydrate from spaghetti being apparently superior to that in, say, rice or bread or maize or oats. I heard stories of teams withholding food from riders after training and racing, "to help them lose weight". Dessert was forbidden of course, except at the end of the Giro when – like well-behaved kids – we were allowed a gelato. Although only if we won.

It was fertile ground for eating disorders, so it’s not surprising that some elite cyclists are unwell. I had an eating disorder myself. For most of my racing career I believed I was fat, severely restricting my diet and purging after certain foods. I wasn’t fat. Although I was also not thin enough that my problem was obvious, I was often under-fuelled for training. The health consequences remain with me decades later, in the form of low bone density and increased risk of fractures.

I don’t blame the team director who shouted at me about the choc milk. My choices were my responsibility, not his. It was also my responsibility to work through the problem, which I did as best I could. I don’t even blame the cult of skinny in cycling as a whole. But in lycra it’s impossible to ignore body shape and you’d have to be totally blind to such issues (which I think very few people are, especially in elite sport) not to be influenced by it. Professional cycling is not a healthy environment.

Eating disorders and RED-S (relative energy deficiency in sport) can cause long-term physical and psychological damage. The problem is more widely recognised in cycling nowadays and there’s help for sick athletes but – disgracefully – usually only when their performance suffers. As long as very thin athletes are doing well, they’re generally applauded for their self-discipline even though they might be exhibiting symptoms of RED-S or disordered eating.

Pro cyclists are autonomous adults, so if they want to sacrifice their health for better performance – or the illusion of better performance – that’s their choice. And pro cycling is very different from the grassroots. But part of the point of elite sport is to inspire. These athletes are role models, the literal poster boys and girls of cycling. I don’t think the sport’s thin image sets a good example. It encourages everyone who watches bike races to assume that skinny is faster and better.

It’s obvious that many cyclists at the amateur level idealise thinness. Telling someone they’ve lost weight is always a compliment. Calorie restriction is totally normalised: "Eating is cheating", "I need to lose a few more kilos", "I only ride so I can eat junk food". Some club cyclists seem more interested in looking thin than riding bikes. Personally, I think trying to be skinny is a rather sad goal in any sport. Not to mention unhealthy.

Admiring pro cyclists for being thin is like admiring Michelangelo’s David for his penis. It seems a little out of proportion and one can’t avoid noticing, but why focus on it? It’s neither good nor bad, and it’s not the main point of the statue. The joy of a masterpiece – whether renaissance sculpture or a great bike race – comes from appreciating the beauty and complexity of the whole.

I do believe elite sport has the potential to inspire, to motivate, and to encourage exercise and a healthy lifestyle – of which balanced diet is a crucial part. But we need to be honest that the physiological extremes of the sports industry are just as unrealistic (for most of us) as size 0 catwalk models. The risk is that we compare ourselves with an ‘ideal’ that’s neither natural nor wholesome, to the detriment of our mental and physical health.

We’re often presented with a false dichotomy between skinny and fat. Marketing has learned that we humans respond better to scaremongering, exaggeration, and simple binary choices. Good vs bad, us vs them, carbs vs protein, healthy vs unhealthy. Whole industries and huge profits are built on selling us stuff that we’re persuaded will make us be how we should be. It’s mostly false: over-simplify, over-promise, a product that will ‘fix’ us, a profit margin based on our insecurities. But it’s incorrect to present nutrition as a choice between taste + obesity vs deprivation + thinness. A healthy diet – and a healthy life – has to be sustainable and for that it must include enjoyment, the savouring of both delicious flavours and happy moments.

There was a time when I’d have been embarrassed to say that I love food, because the menu du jour in professional cycling is spartan functionality. Enjoyment hardly features in carb-loading, let alone in slimy energy gels. A tedious diet is seen as part of the necessary self-denial if you’re serious about your sport. It shows dedication. Conversely, taking pleasure in food is associated with self-indulgence and lack of discipline. I think that’s why choc milk was blacklisted by that DS in Montreal: chocolate is bad for you because it tastes good.

However, in my experience chocolate is a performance-boosting superfood. It helped me win races, for example at the 2014 Giro. I was the team leader but I’d lost time on stage 1 and I was struggling. It felt like I couldn’t ever make the right move, like I didn’t have the form. I worried I was wasting the efforts of my teammates who were looking after me so well.

Five days in, I asked our soigneur Yvonne to buy me some dark chocolate. Oh wow did it taste good after all the boring plain carbs. The next day I attacked on the very first hill, rode solo for 30 km, pulled turns in the break with the riders who bridged across to me, attacked on the final climb to drop them, rode another 40 km solo, held off a concerted chase by the Rabobank Team on the descent, and refused to give up even when the gap narrowed to 11 seconds. I won the stage by such a small margin that the chasing riders were in the finish line photo. [Incidentally, the six-rider chase group included Anna van der Breggen, Marianne Vos, Pauline Ferrand-Prévot (all three from Rabobank-Liv) and Elisa Longo Borghini, among others. – ed.]

After that I ate chocolate every evening – our DS on the Lotto Belisol team didn’t try to stop me, because he had a supportive approach to coaching and put the riders’ health before performance. There are good examples in elite sport as well as bad! At that Giro I went on to win two more stages with uphill finishes, including the finale on the Madonna del Ghisallo climb.

Was it the chocolate that won it? I think so. Even mere anecdotal evidence is better proof than most fad diets. It’s more scientific than judging fitness on how defined someone’s calves are. I think chocolate helped me win precisely because it’s delicious, because it gave me a little mental boost. I hid my recipe for success – just as I had to hide my supply of the 80%-cocoa hard stuff from our team director in 2009. But now the secret is out: chocolate is the mood-boosting performance-enhancing stage-winning food of champions.

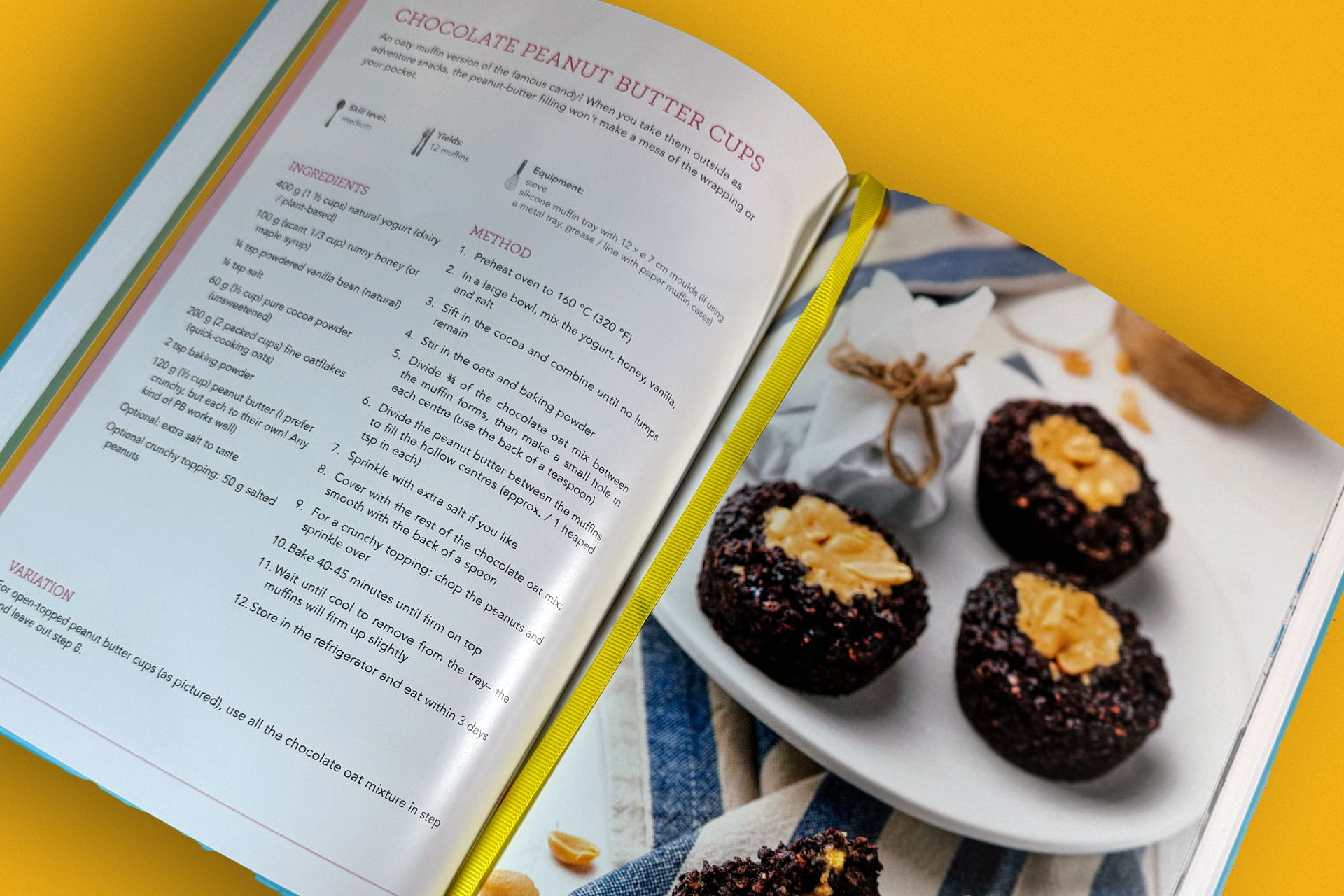

Chocolate Peanut Butter Cups recipe

An oaty muffin version of the famous candy! When you take them with you on the bike as ride snacks, the peanut butter filling won’t make a mess of the wrapping or your jersey pocket.

- Skill level: Medium

- Yields: 12 muffins

- Equipment: Sieve, silicone muffin tray with 12 x ø 7 cm moulds (if using a metal tray, grease / line with paper muffin cases)

Ingredients

- 400 g (1 1⁄2 cups) natural yogurt (dairy / plant-based)

- 100 g (scant 1/3 cup) runny honey (or maple syrup)

- 1⁄4 tsp powdered vanilla bean (natural)

- 1⁄4 tsp salt

- 60 g (1⁄2 cup) pure cocoa powder (unsweetened)

- 200 g (2 packed cups) fine oatflakes (quick-cooking oats)

- 2 tsp baking powder

- 120 g (1⁄2 cup) peanut butter (I prefer crunchy, but each to their own! Any kind of PB works well)

- Optional: extra salt to taste

- Optional crunchy topping: 50 g salted peanuts

Method

- Preheat oven to 160 °C (320 °F).

- In a large bowl, mix the yogurt, honey, vanilla, and salt.

- Sift in the cocoa and combine until no lumps remain.

- Stir in the oats and baking powder.

- Divide 3⁄4 of the chocolate oat mix between the muffin forms, then make a small hole in each centre (use the back of a teaspoon).

- Divide the peanut butter between the muffins to fill the hollow centres (approx. / 1 heaped tsp in each).

- Sprinkle with extra salt if you like.

- Cover with the rest of the chocolate oat mix; smooth with the back of a spoon.

- For a crunchy topping: chop the peanuts and sprinkle over.

- Bake 40-45 minutes until firm on top.

- Wait until cool to remove from the tray– the muffins will firm up slightly.

- Store in the refrigerator and eat within three days.

Variation

For open-topped peanut butter cups, use all the chocolate oat mixture in step 5 and leave out step 8.

Did we do a good job with this story?