You know that old cinematic trope, where there’s a freeze frame of the protagonist’s face, a record-scratch, and a voiceover saying, “Yep, that’s me; you’re probably wondering how I got here …”? That’s probably as good a way as any to start a story that begins with one dodgy website and ends with me half-heartedly URL-squatting on another, masquerading as one of the cycling industry’s leading brands.

So: you’re probably wondering how I got here.

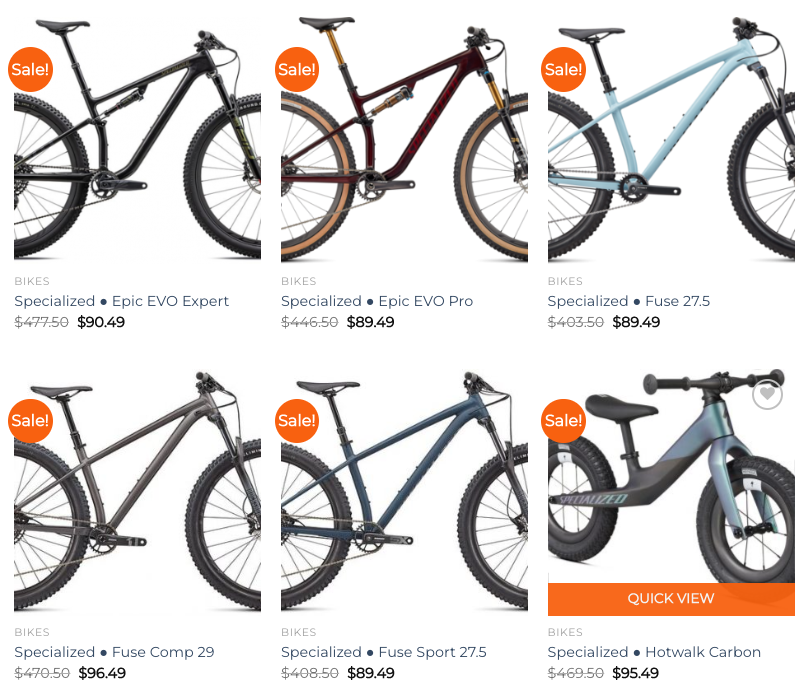

A few months ago I started looking into a vast network of scam stores across the cycling industry and beyond, publishing the results of that search last week. As I learned, there were thousands of stores representing hundreds of brands – Specialized, Shimano, SRAM, 100%, and weirder stuff too, like tap fittings, Disney merch, and cat litter. Their goal was always the same: tricking consumers into paying for products that didn’t exist, stealing their credit card details, and running up charge after charge.

As we know now, this is a sophisticated scam originating in China, with a vast trail of damage in its wake. But I didn’t know that then. I just knew that there was a single website with a vaguely plausible URL (bike-specialized.com) and totally implausible prices.

My best guess at the time was that the scammer was just a lone wolf who’d found an alluring URL and snapped it up from under Specialized’s nose, and was running a not-very-imaginative bait and switch operation. Without realising the enormous scope of the story to come, I started wondering: how easy would that be to execute? How vulnerable are the biggest brands to attacks like this?

Trouble waiting to happen

As it turns out, unless you’re extremely proactive and anticipating every possible cyber-threat, any online business is pretty vulnerable. Looking through domain-name sales website Name.com for gaps in the market, I realised that there were loopholes almost everywhere. If I wanted, I could have bought something that sounded plausible enough to be the URL for any number of brands on the market.

This practice – known as domain squatting, or cybersquatting – can take a range of different forms. There’s typo-squatting, where a lookalike website sits at a URL that might be one character off the real one (eg. colango). There’s combo-squatting, where common words are strung together with a hyphen (eg. shimano-shop). There’s even homoglyph attacks, which use similar non-Latin characters to appear as if it’s the legitimate URL or words (eg. the Cyrillic small letter ‘a’ is a dead-ringer for ‘a’).

As an accumulated whole, it’s a huge issue, too. In 2020, there were 46,000 such websites popping up every week, totalling more than 2 million that year. By 2022, there were almost 1.3 million unique scam websites in Q3 alone, or about 14,000 a day.

The goals can vary, although there’s almost always financial motivation driving the scammers. Usually, the scammers are trying to trick people into buying goods; in some cases, they’re trying to extort brands to buy the URL from them for an increased rate so they can shut them down.

Neither of those were my goal – I just had an idle curiosity about how these things worked. That’s how a couple of months ago, for the princely sum of AU$14.26 (US$9.66/€8.96), I became the owner of the actually legitimate sounding URL: specialized-bicycles.com.

If you think that’s a surprising vulnerability for the world’s most influential bike brand to leave exposed, I’m kinda with you. But there’s method in it. After sheepishly admitting to Specialized that I’d gone gonzo and was URL-squatting, the company’s Global Brand Protection Manager, Andrew Love, treated me with more kindness than I deserved, and talked me through their approach.

“We monitor URLs, but we don’t do too much or proactively buy stuff,” he explained. Instead, Specialized benefits from annual multi-country operations run by law enforcement bodies, such as Europol’s Operation Aphrodite and the US-led Operation In Our Sites. “We’ve done that year after year after year,” Love told me. “It’s just great – you send them a spreadsheet, ‘check it out’ … we always take a dozen or so websites down.”

I wondered if mine would be one of them, next time Europol got on the case – they seem to paint with a pretty broad brush. In 2019, to choose one example, the operation resulted in the seizure of 4.7 million counterfeit products, 16,400 social media accounts and 3,300 websites. But, according to Specialized, there’s not much use to having a URL if you’re not smart about what you do with it. “That domain is useless to you unless you do something pretty professional with it, and then get people to look at you, right?,” Love asked me. “If a tree falls in a forest and Google doesn’t index it, it doesn’t make a sound.”

That search engine sorcery is what differentiates the pests (like me) from the professionals (like bike-specialized.com). The ability to scrape data from real websites, to produce a polished-looking fake one, and to include the right mix of products to show up in Google or Bing search results. In many instances, Love explained, the hackers aren’t just ‘selling’ stupidly-priced bikes: they’re also shrewd enough to include discontinued warranty parts with the correct serial number – something that someone will really want, and be motivated to buy, and to overlook any red flags they might be seeing.

And if a fake website survives the best that Europol can throw at it, and shows up prominently enough to get on Specialized’s radar, there are the brand protection specialists to overcome. I could see the cogs working in Love’s brain as we talked about it, and then, kinda like Liam Neeson in Taken but friendlier, he ran me through the steps:

“Because you’re in Australia, I can come get you. Because if you start scamming people – scamming Americans –well, I’m thinking, do I have contacts in Melbourne? I have contacts in Australia … so, OK. Who would I reach out to? And how would I figure out who you are? You would have to be good enough to hide from someone like me, who’s been doing this for 15 years, right? You’re a bright guy. But do you know all the ways to hide?”

A turn toward the light

I don’t know all the ways to hide. I had a $15 URL that seemed like it should probably belong to Specialized, and no intention of actually trying to defraud anyone with it. More to the point, Specialized weren’t all that fussed – the brand’s Leader of Global PR and Media Relations, Kelly Henningsen, told me with a laugh, “Iain, you can keep it. We don’t need any more marketing sites to manage.”

With their blessing (perhaps ‘awareness’ is more accurate), I spent a bit of time on Squarespace. Industry-leading shitposter BicyclePubes made up some artwork for us, poking gentle fun at the Big S. There were iterations of the website where I had opportunistic ecommerce links to Escape Collective membership, and versions where I tried really, really hard to make it a legit scammy e-commerce venture, just to see if I could. (I don’t think I ever got particularly close, but I’m a journalist, not a hardened criminal – no matter what you might have heard.)

But all the while, the main story kept unfolding – the one where hundreds of brands and consumers were victims, and countless thousands of dollars were flowing into bank accounts in China owned by proper criminals. There were people losing lots of money, and brands across our industry that were really hurting – from titans like Specialized all the way down to small operations making niche goods.

Interview by interview, it became less a story about gullibility online, and much more one about the threats and dangers of an increasingly pervasive, increasingly unsteady digital existence – one where fact and fiction are blurred, where even humanity itself is sometimes questionable. AI is coming, and issues like this are about to multiply – scammers are already harnessing tools like ChatGPT to write more effective emails and texts, or even code entire websites. The genie’s out of the bottle.

In the end, it didn’t feel right to make light of that for a joke website about bike parts that don’t exist. So that’s where I left specialized-bicycles.com – as a contradictory digital artefact; a scam site warning about scam sites.

Did we do a good job with this story?