As much as every cycling event is a test of one’s skill and fitness, the reality is it’s also a test of person-AND-machine. What would be a good bike for a particular job? What’s the best way to optimize your gear for the task at hand? What would we pick for a certain budget? In what we hope will be a recurring series, Debrief will dissect our staff’s choices for various events: what worked, what didn’t work, what we’d do differently. Got any suggestions for upcoming rounds? Let us know in the comments.

I’d already heard a lot about the Breck Epic mountain bike stage race when I signed up to do it for the first time in 2015. Held in the stunning high alpine terrain in and around the ski resort town of Breckenridge, Colorado, it covered more 400 km (250 miles) of distance and ascended more than 10,000 m (32,600 ft) over six grueling days. That type of riding (let alone “racing”) was never my strong suit, but I was drawn to the sheer scope of the terrain and it certainly didn’t disappoint. Despite feeling utterly spent by the end, I’d always told myself I’d do it again.

This was the year. Well, sort of.

Life has gotten a little too busy these days for me to carve out that much time for something that long – and not just for the event itself, but more so the training time required. But when a buddy told our group of friends he’d signed up to do the three-day version with his son and invited us to join in, we suddenly had a crew of seven. Most of them immediately starting seeking a coach to put together training plans (we all definitely like going downhill more than up).

Me? I started thinking about what bike I was going to ride. Go figure.

My Evil Offering daily driver was undoubtedly capable of the task, but being painfully aware of my appallingly mediocre power-to-weight ratio (not to mention my disdain for actual “training”), my first inclination was to tweak the numbers on the other side of that equation by going lighter with my gear – much lighter, ideally. That said, Breck Epic isn’t only about racking up a huge amount of vertical gain; whatever you choose to bring with you also has to survive the trip down the other side, and the terrain at that elevation is anything but forgiving.

In fact, it’s almost the perfect definition of “downcountry” terrain.

The climbs are brutally long and steep. There are sharp rocks everywhere. It’s loose and fast. The air is thin. Afternoon hail storms are common in the summertime, meaning you can start in moondust conditions, but end in frozen slush. Equipment failures are almost to be expected, and while a helping hand is usually just a few other racers away, spare parts are another story.

It’s important to go light at the Breck Epic, but just as important to not go too light.

The frame

I knew that a full-suspension bike with around 120 mm of travel would be the sweet spot based on my previous run at the Breck Epic, and there are no shortage of options there. Specialized Epic Evo? Trek Fuel EX? An Ibis Ripley? Maybe a Norco Revolver? That Revel Ranger I’d recently reviewed? The modern version of the Pivot 429 I used in 2015? Perhaps even Evil’s shorter-travel option, the Following?

I went a little left-of-center and decided on a Rocky Mountain Element Carbon.

Rocky Mountain designed the Element Carbon to be a highly capable cross-country race bike, but one that’s also tailored for riders that prioritize descending just as much (maybe even more) than climbing. The 120 mm of rear and 130 mm of front travel is just a smidgeon more than what’s typically found on XC race machines, the frame is light-but-not-worryingly-so at around 2.4 kg (5.29 lb), and although I hadn’t ever ridden an Element, people I trusted reported the Horst-link four-bar suspension design to be impressively efficient.

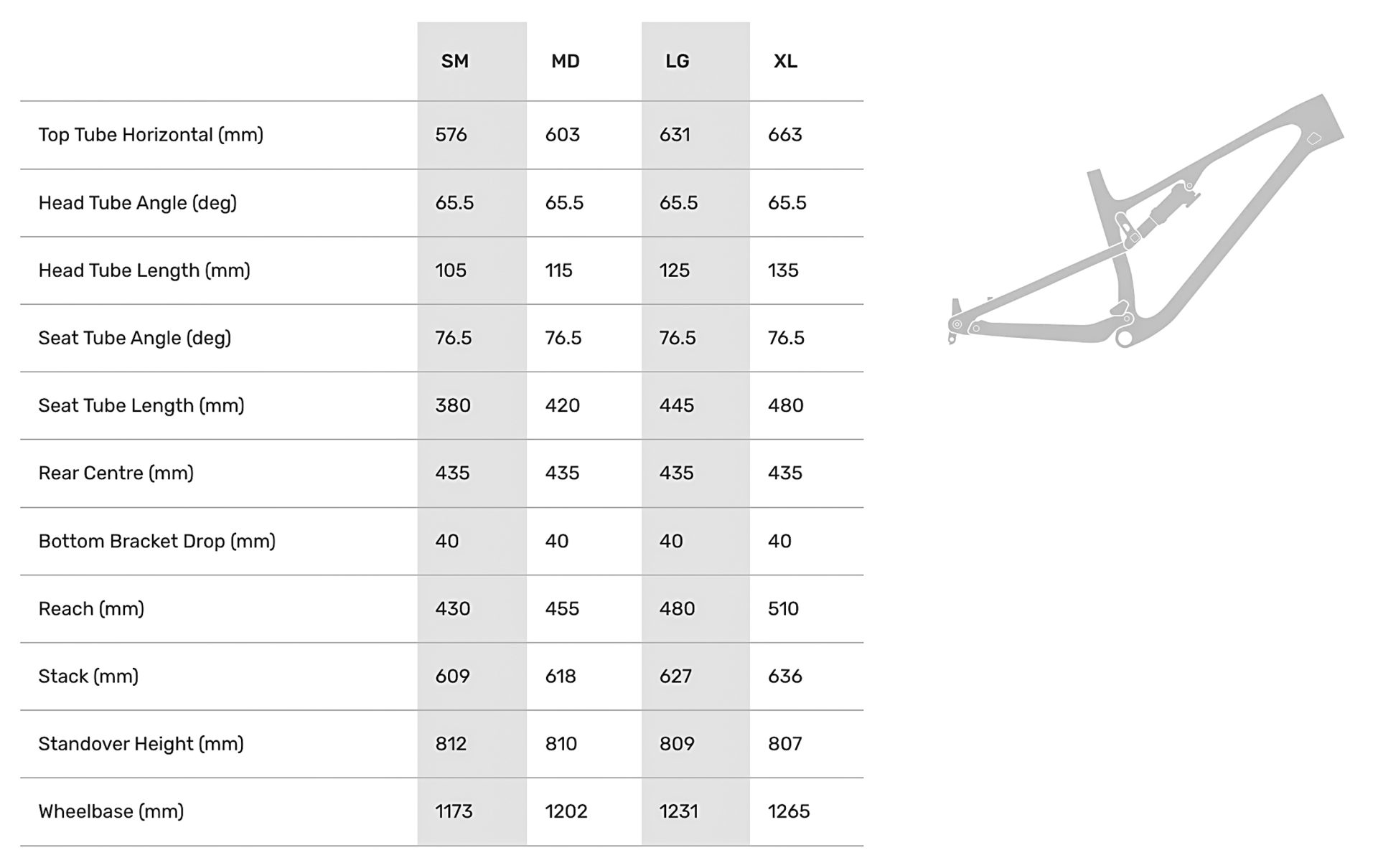

But what put that bike over the top was the frame geometry, which – surprisingly for an XC rig – was nearly identical to my Evil. A long reach? Check. Slack head tube angle? Double check. A steep seat tube angle? Bingo. I wanted to be able to switch bikes without also having to readjust my brain, and with everything matching up nearly to the millimeter, that was enough for me to pick up the phone and place an order for a shiny new Element Carbon 70.

All built up, my medium Element Carbon tipped the scales at 12.47 kg (27.50 lb) without pedals or accessories – not bad at all. But weight weenieism is something we only periodically recover from and never fully get over, and truth be told, the stock build was just the starting point.

The crash diet

The plan was to retain the critical bits of the stock Element Carbon 70 – the fork, the rear shock, the dropper post – with the larger goal being to shave grams without sacrificing capability or durability.

I was in the middle of a long-term test of SRAM’s new GX Eagle Transmission wireless electronic group, so that was a given. And since much of that group’s weight penalty is due to its solid-forged aluminum crankset, replacing it with the recently revamped Praxis Lyft carbon fiber cranks saved 200 g right there.

Likewise, the stock Shimano XT two-piston brakes were traded for SRAM Level Ultimate four-pistons, which knocked off more than 100 g while maintaining similar power. Along those same lines, I also went with Shimano RT-M900 rotors instead of the stock SRAM discs, and in a medium 180 mm diameter front and rear to help tackle the long descents at the Breck Epic. They’re remarkably lightweight despite the healthy size, and previous experience told me the aluminum-core construction would help keep running temperatures down, too – all critical features when you’re descending more than 600 m (2,000 ft) in less than half an hour.

Up front, the original 35 mm-diameter aluminum riser bar and stem was replaced with a softer-riding 31.8 mm-diameter Enve SWP flat carbon bar (now called the M5) and lightweight Ritchey WCS Trail forged aluminum stem (mostly because I had both on hand).

The biggest pile of grams came off with the wheels.

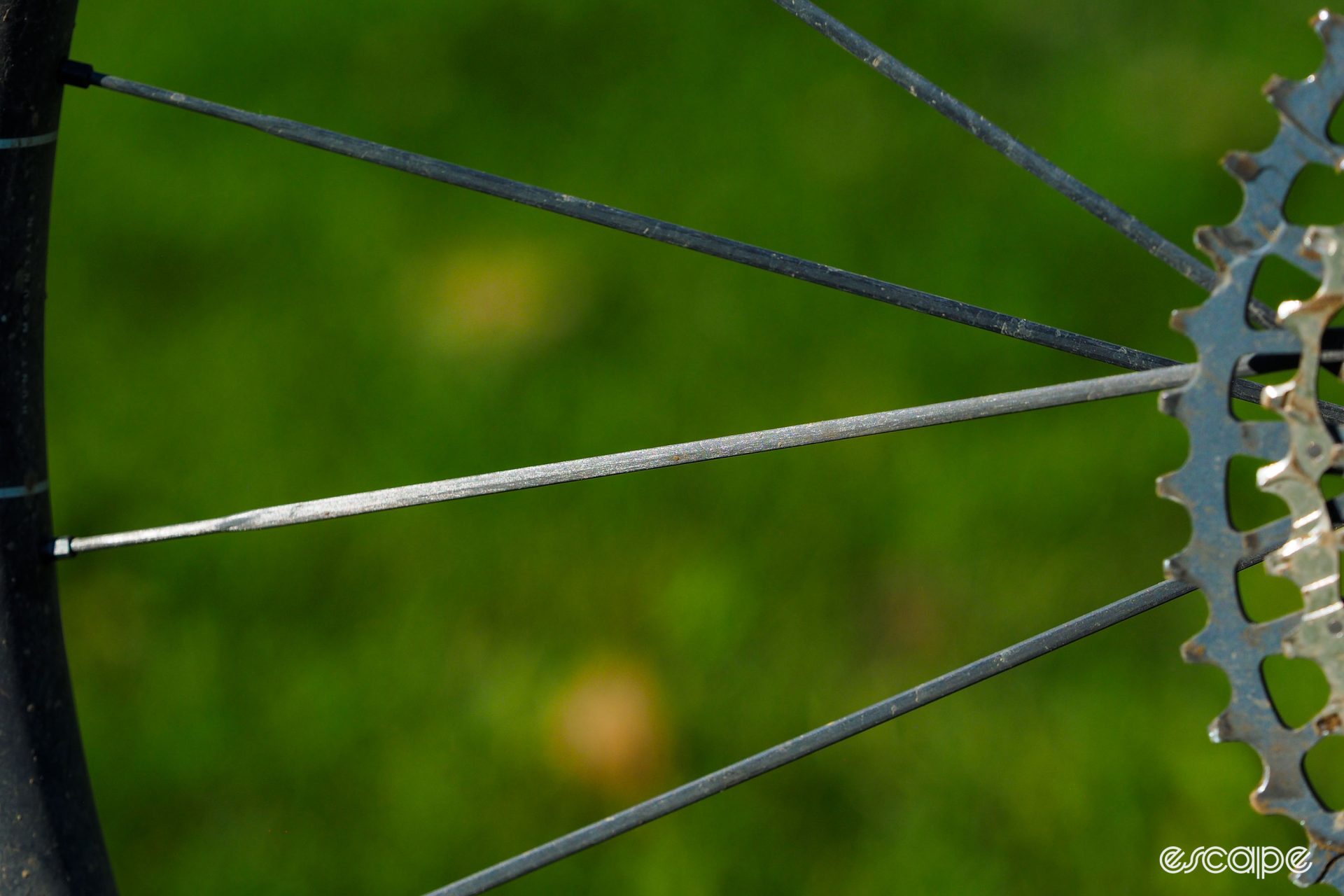

Most carbon fiber cross-country wheelsets measure around 28 mm-wide internally and weigh around 1,400-1,500 g. But I wanted it all: wider and lighter, without sacrificing durability, and without breaking the bank. That seemed like an unreasonable goal until Hunt announced its new Proven Race XC UD wheelset, built with 30 mm-wide carbon fiber rims, unidirectional bladed carbon fiber spokes, and a conventional pawl-type freehub mechanism with a 2×3 pawl layout and a super-responsive 2° engagement speed – all for a retail price of just US$1,700. And best of all, the actual weight was feathery 1,270 g (555 g front; 715 g rear). Bingo.

Tires are an even trickier decision at the Breck Epic. You want something fast-rolling and light to help on the climbs, but the time saved with a quick tire won’t mean much if you slice a sidewall or slide out on a corner coming back down. I tried a whole bunch of options, including a set of Specialized Ground Control T5s (fast-rolling and light, but not enough grip in loose conditions), Maxxis Rekons (decently low rolling resistance and reasonably tough, but not as fast or light as I wanted), the Pirelli Scorpion XC RC (not enough knob for loose rocks), and Vittoria Mezcals (sidewalls were too fragile).

The sweet spot ended up being Schwalbe Wicked Wills with the Super Race carcass and the recently released Addix Soft rubber compound. I knew they wouldn’t be the longest-lasting, but they’re surprisingly fast-rolling given the full-height knobs, impressively light, and offered reassuring (and very forgiving) grip in both dry and wet conditions.

Touch points were another tricky line item. I knew I’d be in the saddle for 4-6 hours each day in demanding terrain, and comfort wasn’t something to be traded for weight. Out back, I ended up with a Specialized Power Mirror Pro saddle with a thickly padded 3D-printed top and reliable titanium rails. It’s not the lightest thing at around 250 g, but previous experience with the higher-end S-Works version confirmed I’d be able to comfortably sit on it all day.

Up front, I opted for Ergon’s new GXR slip-on rubber grips (size large to fit my bigger hands). They featured a shape I already knew worked well for me, they’re reasonably light, and definitely a lot softer than nearly any lock-on grip out there.

There was one oddball component selection: supplemental clamp-on handlebar extensions from obscure Swiss brand Spirgrips. I’d used them ages ago for a 111 km-long single-day marathon MTB event and figured they’d be nice to have on extended road sections.

Mr. Fix-It

Like many other events of its type, Breck Epic features several aid stations along the route where organizers will shuttle your food and gear, and while there is neutral medical assistance should you need it, mechanical support is primarily a DIY affair. Reliability is your first line of defense, and being prepared to repair something on your own is a critical second one.

I mounted to the down tube a Milkit Hassle’off toolkit, which bundled Daysaver’s Essential8 and Coworking5 multi-tools together with a tubeless plug kit, all in a highly compact and weather-resistant case. The Coworking5 also incorporated a spot for a spare SRAM T-Type master link. Milkit’s case design includes an accessory rail on the side, to which I strapped a single 20 g CO2 cartridge and a Specialized Mini inflator head (still the smallest and lightest that I’m aware of).

Underneath the saddle, I attached Specialized’s Mountain Bandit tool wrap, which held an ultralight Tubolito polyurethane inner tube, a second 20 g CO2 cartridge, a double-ended tire lever, a spare SRAM AXS battery, and a CR2032 coin-cell battery (still sealed in its plastic blister case to keep it dry).

I also fitted one handlebar end with a Sahmurai SWORD tubeless plug kit for ultra-quick access, and in my hip pack I added a 2 oz container of tire sealant, a tiny bottle of Squirt wax chain lube, a Dynaplug Carbon Racer tubeless plug kit, and a few spare chain links.

I tossed a few repair items in the aid bags, too. In addition to a variety of food and drink, each bag contained a spare tire, tire sealant, extra tire plugs and CO2 cartridges, spare cleats, and a bunch of extra clothing.

I would have made a great Boy Scout.

When all was said and done, that 12.47 kg (27.50 lb) initial weight came down substantially to 11.34 kg (25.00 lb). Outfitted with a set of XTR pedals and all of the various accessories, the grand total was 12.46 kg (27.47 lb) – a hair lighter than where I started without any of the other bits bolted on.

How it went

Although my body preparation most definitely could have been better, I’m happy to say that the bike performed just as I’d hoped it would.

First and foremost, a word about my approach to the “race” in general: I wish I could remember which of my friends coined this phrase, but I very much took a “winch and plummet” approach to the Breck Epic – just get to the tops so I could blitz the downhills. The Element capably clawed its way up anything and everything my legs and lungs had the power to deliver, with excellent pedaling efficiency and a sufficiently steep seat tube angle to put me in a good body position on Breck Epic’s stupidly steep and long climbs (OMG, Heinous Hill, how I hated you). Aside from a couple of very short paved sections, I never once felt the need to reach for the lockout switch on the rear shock.

Would a little less weight have helped? Perhaps, but not enough to make it worthwhile.

More importantly, I couldn’t have been happier with my decision to go with a little more travel and more trail bike-like geometry on the way down. I derive my joy on the descents when I’m on my mountain bike, and it was absolutely all grins here. Holy crap, was this bike a blast to pilot downhill. Random side hits? Water bar booters? Ugly B-lines? Everything was fair game as far as I was concerned. I may not have had as much suspension or tire as I was used to on my trail bike, but in terms of geometry and handling, it was all so wonderfully familiar.

Despite treating my bike pretty irresponsibly, I had almost zero mechanical issues, either.

The wheels came out the other end looking a lot dirtier than they were going in, but they were as straight and round as they were when I first pulled them out of the box – and while I know for sure a bunch of rocks and sticks got kicked up into the spokes, I wasn’t able to find afterward where any of them had hit. Carbon fiber spokes on mountain bike wheels still scare me a little, but I’d say my confidence level is a bit higher now than it was beforehand.

The brakes were another distinct strong point, with very good power considering how light they are, utterly quiet running (even when the rotors were blazing hot), and reassuringly slow pad wear given the demanding conditions. Granted, I could have used a little more brake on the insanely chunky and fast descent coming off of Georgia Pass, but I wouldn’t have described those conditions are remotely typical XC, either (So. Much. Arm. Pump).

Genuine problems were few and far between.

Exceptionally dry and dusty conditions on Stage 2 had me re-lubing my chain at the second aid station, and I got a pinch flat after having a little too much fun on the fast-and-rocky descent coming down the backside of French Pass. Two plugs and a few seconds swishing sealant around was thankfully all that was needed to fix it, and I was back on my merry way.

That’s not to say I wouldn’t have done anything differently given the opportunity, though.

I’d forgotten that the Breck Epic stages have almost no sections of mellow terrain; it’s either straight up or straight down, with very little in-between. As such, those Spirgrips went mostly unused. In hindsight, it would have been better to save the 100 g and go Keegan Swenson-style with some handlebar tape wrapped around the inboard areas of the bar. That 100 g saved could have then been applied toward some lighter-duty foam tire inserts, like perhaps Tubolight’s EVO SL or HD, either of which would have likely prevented my flat on Stage 3.

I also can’t say I was totally enamored with the SRAM Transmission stuff. As I’ve mentioned in the past, single-shifts were incredibly reliable, and the ability to shift under full load proved handy on one or two stream crossings where there was an unexpectedly steep and rooty pitch coming out of the water. The slowness of multiple shifts has always frustrated me, however, and the varied terrain of the Breck Epic only magnified that further.

Almost without fail when trying to shift multiple gears, I’d overshoot the intended target and then have to correct once the system eventually settled in. Did the system actually shift the correct number of gears, or did I not push the button the correct number of times? Or did I just not wait long enough for it to settle before pushing the button again? Beats me. But this happened over and over, and by the end of three days, I was over it.

I was also fed up with the spotty performance of my Garmin Edge 830. It’s a unit I’ve had for several years now, and no matter what satellite system I select, it’s consistently had issues locking on to my location when I’m in the woods, to the point where I have to run a separate speed sensor on the hub so it at least knows I’m still moving. It was able to track my location just fine on Stage 1, but struggled on Stages 2 and 3, to the point where it kept telling me to make a U-turn because it had no idea where I was. I was thankfully only relying on current and target elevations to mark my progress on course, but I think I’ve had it with this thing now, too.

If I were to the do the Breck Epic again, I’d likely also switch to softer grips, like the Wolf Tooth Components Fat Paw Cam silicone foam rubber ones I was running previously. As much as I loved the shape and tackiness of the Ergons, the firmness was a little too much to bear by the end of Stage 3. And unless I were to set aside some more fitness, I’d maybe opt for a 28T chainring so I could maintain a more reasonable cadence on some of the more ridiculous climbs.

Never say never?

Optimization is a funny thing, because no matter how much effort you put into it, the truth is you’re never actually done. Could I have trained more for the Breck Epic? Even accounting for mishaps (either with myself or in my group), one look at the results sheet will answer that question. But could I have tweaked my equipment even further to suit the particularly demanding conditions of that event? Definitely.

I’ve now done both the full six-day and the three-day versions of the Breck Epic, and despite the difficulty, I still believe it’s one of the best multi-day mountain bike stage races around (and others apparently agree, given how far and wide people came to compete there this time around).

Would I do it again? Every cell in my body is screaming no as I write this, after just a few days back at home.

I’ve done dumber things before, though. Never say never, I guess.

What did you think of this story?