This year marks the 40th anniversary of Gianni Motta-Linea M.D. Italia’s debut as the first American cycling team to race in the European professional peloton, including at the 1984 Giro d’Italia. That fact is widely known, but many of the riders’ own stories have not been told – in particular, the auspicious confluence of events that led to several American racers getting the opportunity to jump from amateur to pro at a Grand Tour. This is the story of two of them.

‘Out of my way, American boy!’

Tim Rutledge was on the descent into Florence when he came off the back of the pack, in the process granting the fervent wish of many of his competitors. It was stage 2 of the 1984 Giro d’Italia and Rutledge, a 25-year-old American on the Gianni Motta-Linea M.D. Italia cycling team, was done in by his equipment as much as his legs.

“We were descending down into Florence and I just couldn’t keep up. I didn’t have a big enough gear to do it,” Rutledge recalls. “So I’m coming off the back of the group and can barely stay on. It was a pretty rugged first day. I think I came in last.”

Technically it wasn’t Rutledge’s first day in the race (that Giro kicked off with an unusual back-to-back of an individual prologue and stage 1 team time trial). But as the first mass-start stage of that year’s Giro, it was a rude introduction to professional European road racing in general.

Barely more than a week prior, Rutledge had been a (talented) American amateur, racing in the Pacific Northwest. Now, he was in a 170-strong pack of pros including some of the most famous in the sport: Giro favorites and former World Champions Francesco Moser and Giuseppe Saronni; Moser’s teammate, the legendary Classics rider Roger De Vlaeminck; 24-year-old talent Moreno Argentin; and the rising young star and 1983 Tour de France champion, Frenchman Laurent Fignon.

Few of them were happy to see Rutledge and his teammates. “They wanted me out of the way. I was a newbie. Their chant to me was, ‘Out of my way, American boy!'” Rutledge says. “They would bump my rear tire with their front tire and do all sorts of things to get me to get out of the way.”

This was not specifically anti-American sentiment or even the broad chauvinism so often at play in national tours of the time, although those may have been factors. Some of it was ruthlessly practical self-preservation. Aside from long-forgotten outliers like Joe Magnani, no Americans had raced professionally in Europe since the pre-World War II Six Days era. The Levi’s-Raleigh team raced the pro-am 1973 Tour of Ireland. A few years later, Americans like Mike Neel, Jonathan Boyer, and George Mount became pathbreaking professional pioneers for American racing’s coming rise, headlined by Greg LeMond’s 1983 World Road Championship. Boyer even led the Supermercati Brianzoli team at the 1984 Giro the Gianni Motta team raced. But an American team, that was something entirely different.

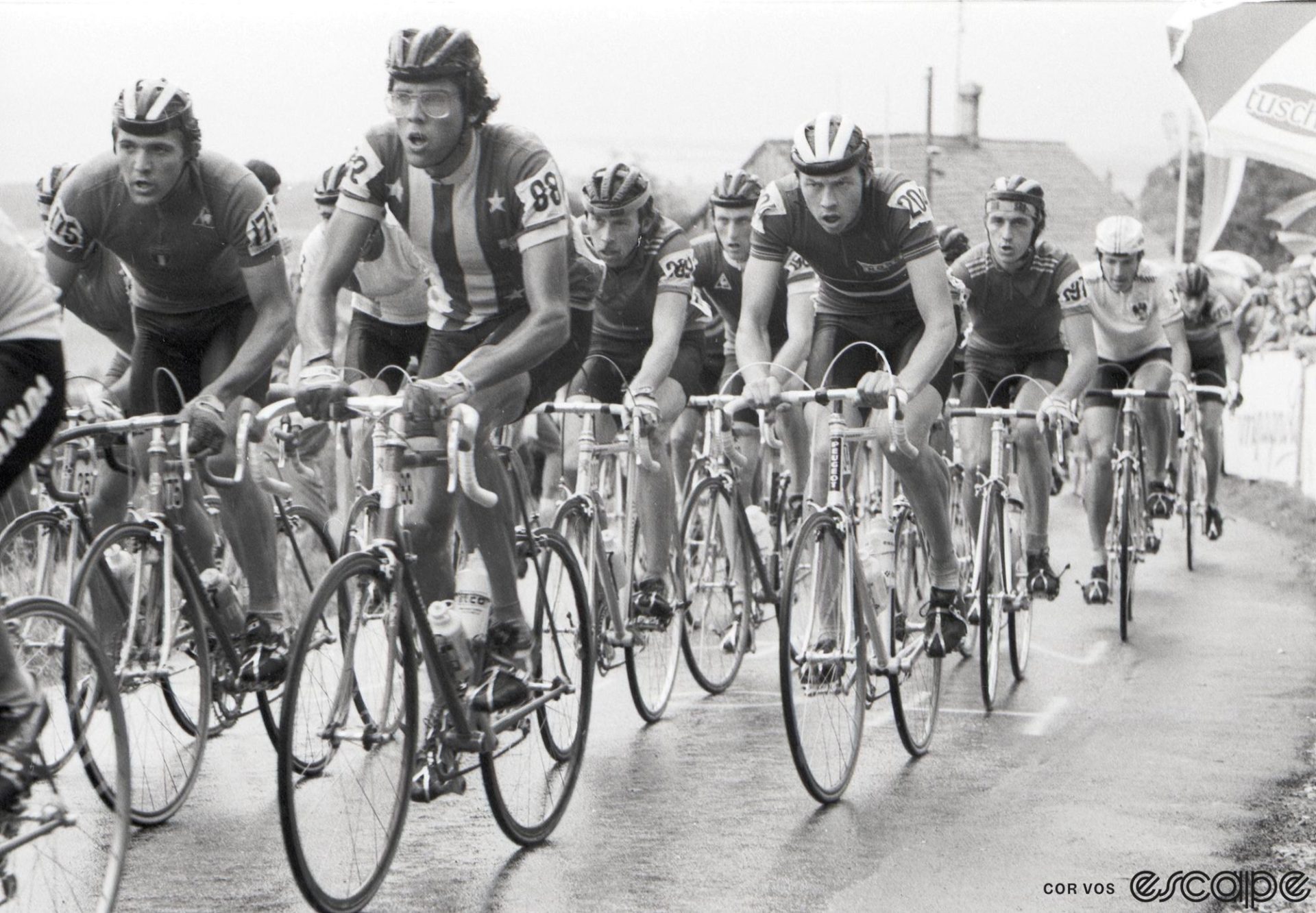

Despite its Italian sponsors and a sprinkling of European riders, Gianni Motta-Linea M.D. Italia had, from its roster to the stars-and-stripes jerseys riders wore, an unmistakable New-World vibe right down to co-founder Robin Morton, the first woman ever to manage and direct a pro men’s team. That freshness extended to the six Americans on the nine-man Giro team. Just one – John Eustice – had any prior experience in the European pro peloton, which made the presence of the squad a clear safety concern for the other teams.

Three of Gianni Motta’s riders – Rutledge, 22-year-old Greg Saunders, and 21-year-old Michael Carter, who had just two seasons of amateur experience, mostly in Colorado – were so fresh the ink on their pro licenses had barely dried by the time they rolled off the start ramp for the prologue in Lucca. Rutledge was such a recent addition to the team he wasn’t even on the Giro’s official printed start list.

And yet, thrown into the deepest of proverbial deep ends, somehow they survived, in one of the wildest and most controversial editions in the race’s history. All six Americans finished the three-week race, far longer than any they’d ever done before. For various reasons, racing fans remember the iconic 7-Eleven team more than Gianni Motta as trailblazers of American bike racing. But the Motta boys led the way, and a year before 7-Eleven’s Ron Kiefel became the first American to win a Giro stage, the Motta team had brushes with near-fame that might have changed the trajectory of the riders’ lives – and even American cycling – had events transpired differently.

An unlikely opportunity

Rutledge grew up in Salem, Oregon, about 50 miles south of Portland, and started the 1984 season as a member of his local amateur team, the Beaverton Bicycle Club. That meant focusing his spring efforts on the Tour of Willamette, an April stage race in the Oregon wine country that Rutledge called home.

It just so happened that Karl Maxon, a tall, powerful rider and gifted time triallist who would later go on to win the US time trial title, and the Gianni Motta team were racing that year’s Tour of Willamette before heading to Europe. That turned out to be a boon for Rutledge.

“I beat all the riders but Maxon [in the time trial],” Rutledge explains. That put him on the radar of the team and rider/co-founder Eustice, who was looking for someone to fill a spot on his squad. “They had just had a rider crash in the Giro del Trentino in Italy and so they needed a replacement rider right away.”

Carter’s path to the team was almost identical, just on a timeline a few weeks earlier. A former competitive swimmer, Carter turned to bike racing while he was in college at the University of Colorado, in Boulder. He did just a handful of events in 1982, but showed enough interest that he went to Italy for a training camp, and returned to Europe in 1983 for some amateur races, where categories were grouped together in mass start events “almost like a Gran Fondo,” he recalls. In the U.S., he jumped from Category 4 beginner to Category 2 (elite amateur) in just a few months.

As a freshly minted Cat. 2 with still-developing pack skills, on one warm, windy stay in an April stage race on Colorado’s Front Range, he was nervous about being in the 120-rider peloton on a flat course exposed to the gusts. “I went as hard as I could right from the gun,” he recalls, and even though there were top Americans and even some European pros racing, less than a dozen riders went with him. “Every time someone wouldn’t pull through, I would attack,” and eventually the group was down to just him and two Levi’s-Raleigh teammates, Hugh Walton and Roy Knickman. The trio put six minutes into the field; Carter got third overall. One of the riders he dropped that day was Dag Selander, a Norwegian on Gianni Motta.

“Robin called me Monday” after the race and said, “We’re going to race in Italy and we need a climber. Would you like to go do the Giro?” Carter thought for about two seconds before saying yes. He was on a plane less than 48 hours later, after telling his mostly baffled professors that he needed to finish his coursework in summer. In a 2013 story by Ian Dille for This Land, Saunders, who had done some amateur races in Latin America with the U.S. National Team, described a similar approach by Morton at a race in Texas. “I thought she was joking,” he recalled of her overture to turn pro and race in Europe.

All of this raises the question: why did Rutledge and Carter, two obviously talented – but obscure and unproven – amateurs get the call? Saunders, too? What propelled those riders from modest-sized American pelotons and regional pro-am races to one of the most storied events in the sport?

The short version is this was 1984, and the Gianni Motta squad was in dire need. Motta – the 1966 Giro champion – was sponsoring an American team because he’d opened an American office for his bicycle business. He needed American riders. But 1984 was an Olympic year, and not just any: for the first time in half a century, the Summer Games would be held in the U.S., in Los Angeles. Especially with the Soviets boycotting (as the U.S. did for the 1980 Moscow Games), the American team had serious medal chances, and the riders – Davis Phinney, Kiefel, Alexi Grewal, and others – to achieve them.

But the Olympics were for amateur racers (this changed in 1996). While Phinney and his 7-Eleven team – “effectively the US national team,” says Carter – were the top outfit in American racing, and Levi’s-Raleigh with Knickman and Thurlow Rogers not far behind, none of those riders could turn pro without giving up their Olympic dream. The few established American pros, like Boyer and LeMond, already rode for other teams. So Morton and Eustice had to look elsewhere, and that meant finding talented amateurs who weren’t on the Olympic shortlist.

As Rutledge puts it, his qualifications essentially were that “I had done well at the Tour of Willamette and I had a passport.” He was “willing and able to go,” and had proved himself against Maxon. While Carter and Saunders joined the team earlier and had done a few Italian pro events, Rutledge, as the last addition to the team, had no such introduction. Within days of accepting Morton’s offer, he was lining up at the Giro d’Italia for his first pro start, just one more unusual sight on the first American-registered team at the race.

First, you survive

The first obstacle was simply fitting in. Some of the chilly reception to the team was open sexism directed at Morton, the team’s co-founder. “Women had never been allowed in the caravan,” Morton told CyclingNews’ Susan Westemeyer for a story in 2009. “I was under a microscope the entire time.” One day at the Giro, captains of several teams presented her with a vegetable “bouquet” arranged like male genitalia. “She was just trying to survive herself,” recalls Carter of the trials Morton faced.

Not everyone was hostile to the Americans. Fignon’s teammates on Renault-Elf, in particular, were “kind” and helpful, Rutledge remembers. The soft-spoken Charly Mottet, then a second-year pro on Fignon’s team, always had an encouraging word, says Carter. And “Michael Wilson, a really strong Australian on Alfa Lum, became one of my best friends,” he recalls (Wilson had won a stage at both the 1982 Giro and 1983 Vuelta a España and would finish eighth overall in the 1985 Giro). “He was just so supportive.”

The Italians were another matter, however. Rutledge says that Argentin especially was on the aggressive side. “Huge asshole,” confirms Carter, adding that Argentin told him one day, “You shouldn’t be here; you don’t belong.” The message was delivered in Italian, but Carter studied the language in college and spoke enough “street Italian” to clearly understand what was said. Moser gave some gruff advice, also in Italian: stop touching your brakes, maybe you need to go home, that kind of thing. Still, Rutledge says Moser was mostly aloof and “wouldn’t have bothered” with the Americans unless they were in the way. Which they tried very much not to be.

Daniel Franger was one of the few Americans on Gianni Motta with any real European racing experience; he’d done the amateur Settimana Bergamasca stage race the year prior, says Carter. “He’d say, ‘Just ride with me in the middle,” and try to hold position. “But I wasn’t used to close proximity at all. The Italians and Belgians would scream at us,” which made it even more nerve-wracking.

Carter was terrified of causing a crash, particularly one that took out a big-name rider. Weeks earlier, at his first race with the team in Puglia, Carter watched as a teammate, Frank Scioscia, accidentally overlapped wheels with Tommy Prim, the Swedish star who won Tirreno-Adriatico that year and had twice finished second at the Giro; Prim fell heavily and broke his collarbone, Carter recalls. Not long after, Scioscia went back to the U.S. (and would go on to run the Shaklee team), but the experience seared Carter. “I did not want to be that guy,” he says. “It scared me to death, so I said, ‘OK, I’m just riding at the back.’”

Even the most prominent American in the Giro wasn’t much help. Carter says he approached Boyer early on and asked his advice. “He was an icon, right? So I asked him, ‘What can you tell me? How do I do this?’ And he just looked at me and said, ‘Expect the worst and hope for the best.’”

Gradually, they did learn how to survive. “But believe me, it took a lot to figure it all out,” says Rutledge now. Among the many things that he had to learn literally on the fly – again, in the middle of a Grand Tour – was how to pee on the bike.

“I had never done it before, so I needed to learn how to do that and do it properly,” Rutledge says now. “My teammates went out and taught me how to do it.”

Polémica!

Even as Rutledge, Carter, and the other young Americans on Gianni Motta were climbing that steep learning curve, the Giro itself became consumed with controversy. Until relatively recently, national tours like those of Italy and Spain were dominated by home-country riders, which was a source of pride even for the organizers.

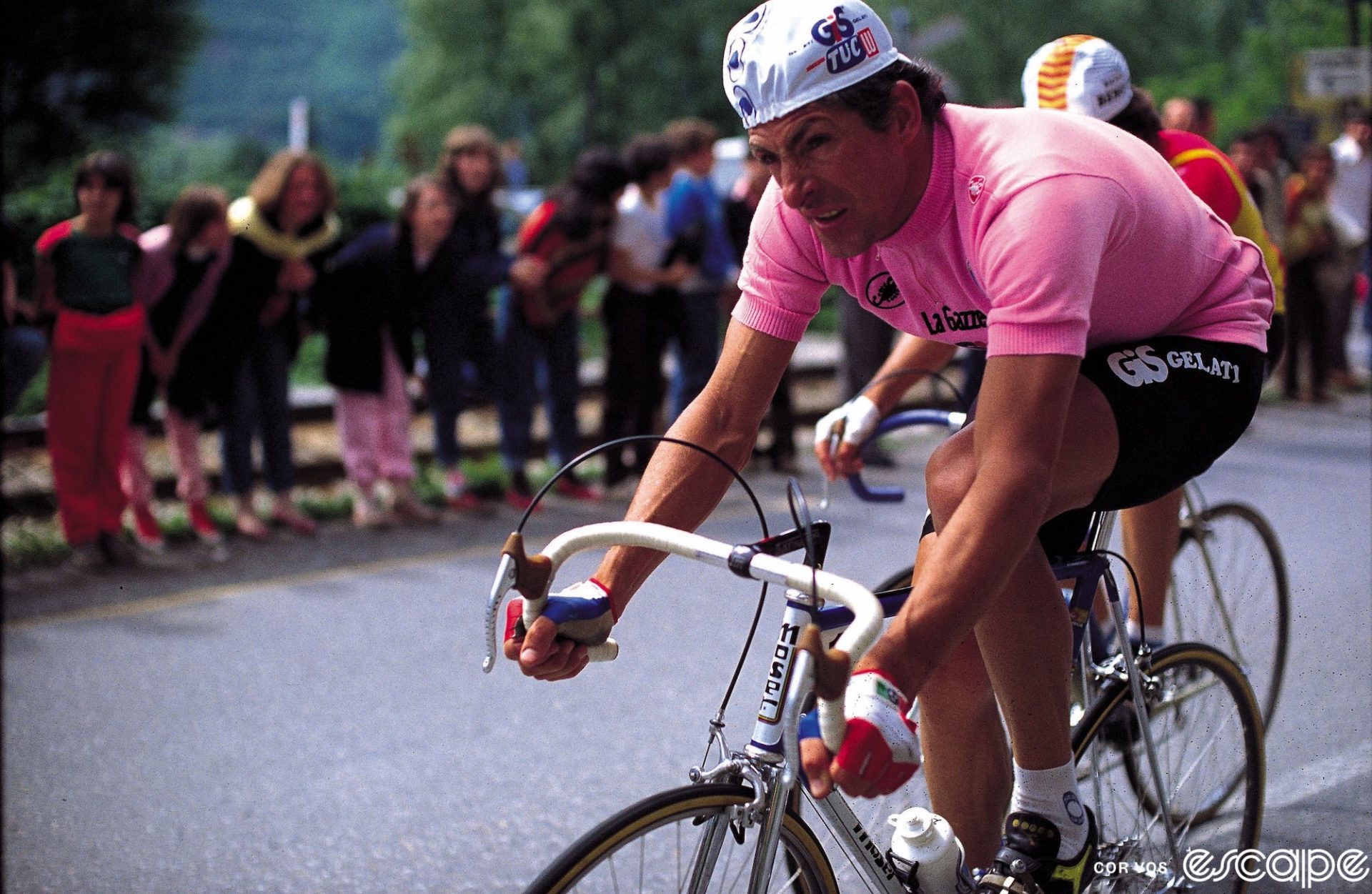

As cycling historian Bill McGann writes in “The Story of the Giro d’Italia,” the 1984 course had been designed to favor Moser or Saronni, but especially Moser, a three-time Giro podium finisher who was in the midst of a remarkable season that had already seen him win Milan-San Remo and break Eddy Merckx’s 12-year-old mark in the World Hour Record. What stood in his way was Fignon, the Frenchman.

He was a formidable threat. As McGann writes, “Fignon won the Tour [de France] in his first attempt, in 1983. Not only had Fignon won it, he won it with startling ease.” Moser would have the advantage in the 140 km of individual time trials, and on flatter stages. But, writes McGann, “the climbing, where Fignon enjoyed a marked superiority over Moser, leaned to Fignon’s advantage because of a planned ascent of the Stelvio in stage eighteen.”

The two riders fought a close battle across Italy but, entering the crucial stage, Moser held the pink jersey with Fignon in fourth, just over two minutes behind. There’s still debate about what happened that day: Was the Stelvio really blocked by snow? Was the pass open and did Giro organizers want to run the stage, only to be shut down by a government official in Moser’s nearby hometown of Trento, who refused to open the road? Or did Giro organizers take action themselves to protect the Italian’s lead?

Whatever the case, the race skipped the Stelvio entirely for a longer route with two shorter climbs, including one early on. Fignon attacked anyway, and a dropped Moser reportedly was pushed by fans on the climbs and illegally drafted team cars as he fought his way back. But the race jury declined to penalize him, even as it docked Fignon 20 seconds for an illegal feed.

France erupted in fury at the “hometown” treatment of its hero, and the French magazine Vélo published photos showing a snow-free Stelvio. (Carter maintains that the route was easily passable.) An incandescent Fignon ripped the race open two days later to re-take the overall lead. But more shenanigans followed in the final-stage time trial, as the TV helicopter covered Moser’s and then Fignon’s rides and supposedly positioned itself behind the Italian for a bit of rotor-wash tailwind, while Fignon was filmed from the front. Moser (who disputes that the helicopter played a role) won the title by just 63 seconds over Fignon.

As the Motta riders’ fitness and confidence slowly improved, Rutledge began to notice that the organizer’s less-than-uniform application of the rules affected his own race, saying that the official results often listed his finishing time as worse than it really was. They would put him with one group at the finish even if he made up ground late in a stage and got into a different one with a better time.

“Let’s say I’m two minutes behind, right? They’d have me at three,” he recalls. “They would see you out on the course, and I would never just give in in the last 10 kilometers or whatever. I would keep charging, and that’s where I made up a lot of my time, towards the end. Most riders back then they would just succumb to, ‘This is my finish time, this is the group I’m with, I’m not going to do any more.'”

Rutledge says the effect on his morale of the persistent timing errors was “mind-blowing,” but he nevertheless kept pushing on.

‘Tim is up there; we can do this.’

The Gianni Motta team came to the race with modest expectations, at least for most. But as the riders adapted to the rigors of racing in the European pro peloton, they began to have an encouraging series of results.

It started on stage 4, at 238 km one of the race’s longest, when Maxon went on a solo attack. The rest of the field was only too happy to let the silly American get up the road. While the Italians had no intention of gifting anything, they didn’t account for Maxon’s time trial talents, and he gained as much as 22 minutes on the field, making him virtual Maglia Rosa, race leader on the road. While he likely wouldn’t have held a sufficient gap to become overall leader, a stage win was a distinct possibility, until Fignon crashed and an opportunistic, Saronni-led chase caught Maxon with under 20 km to go.

After the catch was made, it was up to Rutledge to help his shattered teammate make it to the finish as they fell behind the caravan. “I was to stay with him and get him home with whatever means possible,” Rutledge recalls. “Some of that was pushing that you couldn’t see. And then to feed him.” In the days before gels and modern race nutrition, Rutledge says, “what he ate was a cup of strawberries. That was his energy food.”

Maxon missed out on the pink jersey and a stage, but it turned out that his 200+ kilometer effort was the longest solo breakaway in race history; Gazzetta dello Sport and other Italian papers covered the feat, but to Rutledge, there was an even more rewarding outcome: “Karl proved that an American rider could be with the best,” he says.

More opportunities followed as the riders’ confidence grew. Stage 11, from Isernia to Rieti, was a monstrous 243 km into central Italy’s hilly Abruzzo region; it was one of four stages that year longer than 240 km. It was also raining.

“We came in to finish on this stage and it was a tough go in the rain, and that’s the day that I got on the wheel of Roger De Vlaeminck, and he was my hero,” Rutledge says. (As it happened, De Vlaeminck, one of just three riders ever to win all five Monuments, had almost been a teammate; he raced part of the prior season with Eustice and Dag Selander on the Gios-Clement team that Morton and Eustice founded.)

“I got on his wheel with about, I don’t know, 15 kilometers to go, and I was bound and determined that it was his day. In the rain, the bad weather, he’s the guy, and I got on his wheel,” Rutledge recalls. He would eventually get bumped off by another rider in the rough-and-tumble finale. But Rutledge’s instincts of which wheel to follow were dead-on: De Vlaeminck only narrowly lost the sprint to Urs Freuler.

Rutledge also got in a breakaway later in the Giro, a “suicide” solo effort that he doesn’t technically consider a breakaway and which did not come to anything, but at least he can say he was off the front in a Grand Tour. But to Carter, it was an important inspiration. “It was so encouraging,” he says of the move. “It was like there was life for us. ‘Tim is up there; we can do this.’”

Carter had also gone from spending all his time at the back of the pack to probing the front. Somehow, he felt like he was getting stronger as the race wore on and he lost significant weight. “I came into the Giro at 153 pounds, and by the end I was 132,” he recalls. So when the late mountain stages came, he decided to have a go in the break himself.

The first attempt was marked by an incident when Flavio Zappi, wearing the King of the Mountains jersey, ran into Carter while going back to his team car and crashed. Remounting, Zappi rode up to Carter and began berating him, even though Zappi had caused his own crash. “We had been dealing with all this stuff” the whole race, Carter recalls with a hint of exasperation at the memory. “Yelled at for stuff that was like, ‘No, you’re just being a whiner.’ It was just getting old.” So Carter yelled back. “I said, ‘Screw you! I’m not going to let you intimidate me!’ And the next day I made sure I was in the break again, right there with him.”

Just being at the front should have been a resounding success for such a small, inexperienced team. But it apparently wasn’t enough for Motta, who’d used personal influence to wrangle the team’s invitation to the race. As progressive and far-sighted as he was in ways like positioning his brand for the rise of American cycling, or the role of women in sports, Motta was decidedly old-school in others, says Carter, particularly training. “No ride, no eat,” was one of his aphorisms, and even on six-hour training jaunts riders were to consume only water, no food.

On the day Maxon made his massive breakaway, Carter recalls, when he finally got caught, Maxon “was just pedaling squares” he was so cooked. At the finish, Maxon was mobbed by the press, the coda to a day-long media bonanza. But Motta was mad that Maxon hadn’t finished with the field. “We were super pissed [at Motta],” recalls Carter. “[Maxon] just got hours and hours of television [time], and you’re mad he got dropped?!”

Things got worse. “Our deal was we got paid halfway through the race, and then we got the balance due when we finished the race,” says Carter. Late in the race, it became clear to Motta that the team wouldn’t get the lofty, unattainable results he’d envisioned, but most of its riders would finish – only Claude Michely, from Luxembourg, and Belgian Guy Janiswewski, both over the time limit on stage 14, had left the race. “I’ll never forget it,” says Carter with a touch of awe. “We’d just done this really long stage in the Dolomites and it was cold, pouring rain in late May or early June, and at dinner that night he only let us have soup.” Carter saw it as deliberate sabotage: “He didn’t want us to finish, didn’t want to have to pay us.” (Carter says he snuck out of the hotel later with Saunders and got a pizza.)

Morton was dealing with her own major issues. According to the CyclingNews story, Motta wasn’t paying the bills, including expenses, so she maxed out her personal credit cards just to keep the team in the race. Frustrated, she tried to quit and go home, but says the riders and staff wouldn’t let her (the exact word she used was “kidnapped”).

Somehow, all six Americans, including the rookies Rutledge, Saunders, and Carter, finished. Even the gruff hostility of the Italians softened. As Saunders recalled for This Land, when he suffered through the second-to-last stage with a bout of food poisoning, some of them pushed him along, telling him, “We’re almost done; you have to finish.” After 22 stages and a prologue, across 3,808 kilometers and tens of thousands of meters of climbing, Carter was 118th, two hours, 42 minutes, and 52 seconds behind Moser. Rutledge was 141st, two spots ahead of Saunders, the Maglia Nera, or last overall finisher, at four and a half hours down.

Opportunities earned, not always taken

Improbably, the acrimonious end of the race didn’t spell the end for either Rutledge or Carter’s association with the team. With the Giro under his belt, Rutledge had earned a break, but he didn’t take one. Instead, he went to the Tour de Suisse.

“That was stupid, to ride in a stage race so close behind another one. It’s terrible on your body,” Rutledge says now. “I blew my system out and had Epstein-Barr.”

The virus, which is so widespread an estimated 90 percent of the world’s population has been infected, is often asymptomatic. But it is responsible for infectious mononucleosis (also known as glandular fever) and is associated with a bevy of other health problems including chronic fatigue syndrome. Mark Cavendish, Stefan Küng, and Chloé Dygert are just a few of the numerous well-known cyclists who have dealt with its effects in recent seasons.

For Rutledge, a bout with the illness knocked him out of the Tour de Suisse and ultimately spelled the end of his 1984 European adventure.

As it turned out, that would be the end of his European road racing career too. He had been all set to spend the following season with the team, which retained many of the same riders and picked up Xerox as a new sponsor to replace Motta, but those plans fell apart when he asked to be paid.

“I think I’ve earned my spot, and they didn’t want to pay me. All I asked for was a thousand dollars a month in order to keep up a Portland apartment,” Rutledge says of his modest demand, which went unmet.

Instead, Rutledge went back to racing the Pacific Northwest scene. He would return to Europe in the future to race cyclocross, but his time in the pro road peloton across the Atlantic consisted of one Giro and part of a Tour de Suisse.

But Rutledge’s path did lead to his increasing involvement with cycling, both in the industry itself, and in race organization and the all-around growth of the sport in the Pacific Northwest. He spent years developing cyclocross bikes for Redline, then Raleigh, and then Redline again, during the discipline’s heady 1990s and 2000s.

He was also involved in team management at the helm of Redline’s cyclocross squad, where he had a major impact on plenty of recognizable names in the US ‘cross scene. In that capacity, he helped youngsters like Logan Owen – whose haul of age-group national titles reaches into the double digits – develop into young pros. Of course, Rutledge kept racing on his own along the way even after his pro career had long ended, and he counts two Masters national titles on his ‘cross palmares.

Initially disgusted by his treatment by Motta, Carter went home and resumed school and briefly joined the Marines. But he kept racing, and some of his interactions at the Giro stuck with him. “There’s something to this sport,” he thought. The next spring, Morton called again. Xerox was racing the Vuelta a España. Did he want in? Carter regretted not racing the 1984 Tour de Suisse. “I should have done it because I had the form,” he says now. He wasn’t going to miss that chance again.

He lasted 13 stages at the Vuelta. But he also saw the sport’s worst moments – like witnessing fatal crashes – and left racing for a time. He joined the Navy to fly fighter planes, but he simply couldn’t wash pro cycling out of his system and left the service before completing flight training. A long, winding path led eventually to a one-year stint on Motorola and third overall in the 1991 Tour de Romandie before riding that year’s Tour de France for the team, and he raced domestically and internationally through 2006 for several teams.

While the 1984 Giro didn’t lead to immediate racing success for Rutledge or Carter, neither of them regrets saying “Yes” to Morton that long-ago spring, “Yes” to something that, to that point, so few Americans had achieved you could count them on one hand. Now battling cancer and looking back four decades after his Giro debut – and swan song – Rutledge says, “I’m so thankful for the opportunity I got. Not many guys got there.” He acknowledges his brief pro career was unusual, from its abrupt start to unceremonious finish. “I was racing here domestically, racing great, and my old teammates were like, ‘What? You are doing the Giro? And I’m doing …?’ It certainly was a bit of that and I don’t blame them, I’ll admit.”

But one thing is for certain, Rutledge thinks. No matter what his background was entering the Giro, no matter what the Italians thought or said about his right to be there, and no matter what happened after that derailed his career before it ever really got going, he’s sure of this: “I know that I did earn it.”

What did you think of this story?