Trek has just joined the growing number of brands that now only offer a single race-focussed model. With the Emonda disappearing from the range, it’s a full-circle moment for the American bike company.

Trek launched the Madone in 2003, and for a time, it was a mostly round-tubed race bike focused on weight. Over the years, we saw the Madone take a path of aerodynamics, and by the mid-2010s, it had gained enough weight for Trek to introduce a new weight-focused model – the Emonda.

The choice between the aero Madone and lightweight Emonda has remained until today. Want both aero and light? Well, Trek didn’t really have a good answer for that. And that leads us to the new Trek Madone Gen 8, a bike that aims to match the Emonda in weight and the Madone in aero.

In this article, I’ll cover what’s new, where the claimed gains are, what has seemingly been lost in the model consolidation, and some initial hands-on impressions. Consider this a detailed first look rather than a full review. Ronan Mc Laughlin will hopefully fill in the gaps at a later date.

Good stuff: Improved ride quality, unapologetically a race bike, unique looks, easily adjustable stem height with efforts taken to simplify headset compatibility, Madone SL now lighter than previous SLR, and now equipped with appropriate tyre widths.

Bad stuff: Still not the lightest option nor the most aero bike Trek could make, Trek's own aero bottles are an integral part of the bike's aero performance, headset still lacks sealing.

Lighter. Smoother. Less aero?

According to Trek, the new Madone is just as light as the previous Emonda, just as aero as the out-going Madone Gen 7, and more comfortable than both. There are truths to such claims, but as I’ll get to, they’re also not telling of the full picture.

While the new Madone Gen 8 looks like the Madone before it, the company claims to have started from a blank page including considering traditional and non-traditional designs, dropped seatstays, traditional seatstays, and some pre-existing Trek concepts. In the end, the Madone’s familiar form factor and unmistakable IsoFlow seat tube won over in efforts to improve seated comfort while keeping a check on weight and aerodynamics.

From afar it may look a whole lot like the Madone Gen 7, but a close look reveals a number of key tubes that have now been optimised for weight reduction over absolute aerodynamics. For example, the down tube is more rounded than before, while the seat tube doesn’t follow the contour of the rear wheel in the same way or have nearly as much depth to it. It's a similar story up front with the now-shallower fork blades. That distinctive IsoFlow seat tube hole is refined in shape, now smaller, and said to be lighter, more aero, and more flexible.

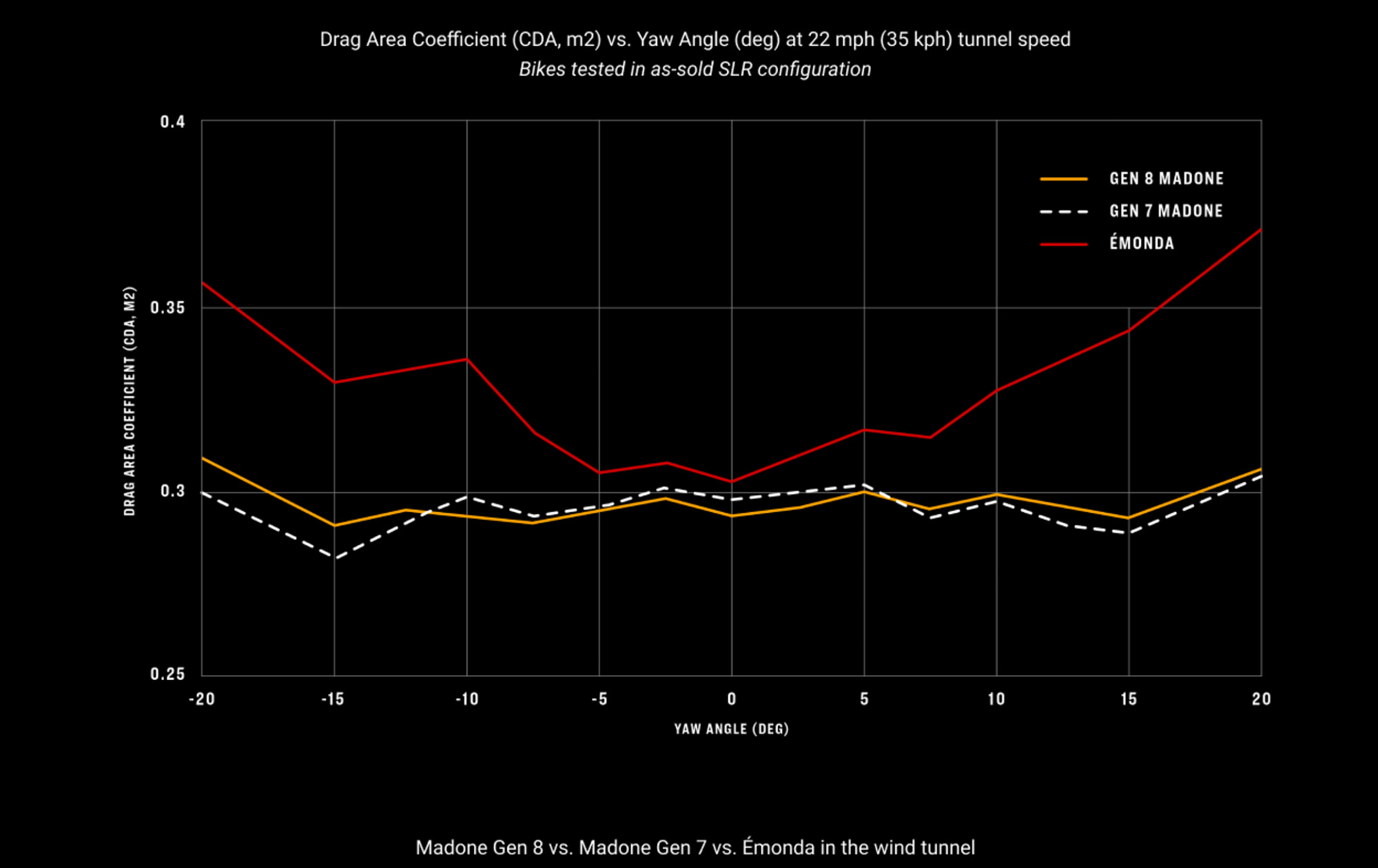

Of course, Trek claims that its new Madone SLR Gen 8 is just as fast as its predecessor and runs rings around the Emonda (which was not known to be a slippery bike). Gone is Trek’s previous commitment to the Kammtail Virtual Foil (aka, truncated airfoil shapes) which largely existed for the UCI's now-discontinued 3:1 length/wide tube cross-section rule. Now, the company is coining the phrase “Full System Foil,” where a cross-section taken of the whole bike reveals a deep airfoil shape that includes the new aerodynamic bottles.

To be frank, Trek’s claim that the new Madone is faster is not an apples-to-apples comparison. The figures used include the new aero bottles in the measurement of the new bike, but round bottles are used in the figures for the older version. At straighter yaw angles and as a complete bike package (including those bottles) the new Madone Gen 8 is said to be faster by a small margin. Even still, the previous Madone remains the faster pick at high yaw angles beyond 10º, and it’s likely the difference would extend further if those speedy bottles were fitted to the older model.

If you compare an apple to an apple, you'll see the results flip in favour of the Gen 7 version, with Trek claiming a 1.6 W delta (at 35 km/h) in a straight line when comparing both generations of Madone set up with round bottles.

I’m not wanting to republish the company’s white paper on the topic, but a number of the claims surround the idea of testing the whole bike as a system, not just with the aero bottles, but also with a rider onboard, too. For instance, the new handlebar features a taller and blunter profile which, according to Trek, would measure slower if tested in isolation. However, with a rider in place, Trek claims the less-aero shape helps to reduce the drag on a rider’s moving legs, and therefore comes out as a net gain.

There are countless “it depends” moments when discussing aerodynamics in cycling, and it’s trivial to argue over fractions of a watt if efficiencies are made elsewhere. Still, it seems likely that Trek has left some potential aerodynamic gains on the table in pursuit of reducing weight and improving the ride quality.

The new flagship Madone SLR Gen 8 frame carries a claimed weight of 796 grams (M/L, lightest paint, no hardware), with the matching fork at 350 g. There’s also the more-affordable Madone SL, with a claimed frame weight at 1,054 g, and a fork at 363 g. Compare these figures to the Madone SLR Gen 7 with a claimed frame and fork weight of 1,050 g and 418 g respectively. Or the company’s Emonda SLR with a claimed frame weight of 760 g and a fork at 381 g.

Add in the now 25-30 g lighter RSL Aero one-piece handlebar of the Madone SLR, and the company claims its full bikes are on par with where the Emonda previously sat. That all said, the bikes still aren’t at risk of breaking the UCI’s 6.8 kg rule, with Trek’s lightest Madone SLR 9 build sitting at 7 kg before the addition of cages, computer mount, or pedals. Meanwhile, my Madone SLR 9 Project One sample in a medium size and with the Lidl-Trek paint scheme tipped the scales at 7.13 kg with tubeless tyre sealant, Trek’s new aero carbon cages, and computer mount, but no pedals. Add pedals and you’re approximately half a kilogram (a pound) away from breaking the UCI’s weight limit.

Certainly, the use of a few shallower and more traditional tube shapes helps with some of the weight reduction achieved, but most of the savings are made in ways the eyes can’t see. With the new Madone Gen 8, Trek has introduced a new flagship 900-Series OCLV carbon lay-up for its SLR models, effectively a stiffer and stronger material that allows for less of it to be used (hence, weight saved).

At the same time, Trek has made a few changes to how its frames and forks are manufactured. The frames are now constructed with 3D silicon moulds that exactly match the internal frame shaping with the goal of providing improved and better-controlled material compaction. The forks are now being moulded as a single piece instead of the previous approach of bonding multiple pieces into one. The result is less unnecessary material overlap, and some significant weight gains just in the fork alone.

Trek made further improvements by moving to two distinct sizes of tube shapes, one for the three smaller frame sizes and another for the larger three. While not a new concept, such size-specific frame design does mean the smaller sizes are better optimised for smaller riders, and vice versa.

Finally, we come to the improved vertical flex in the IsoFlow seat tube. Trek claims the new Gen-8 Madone is 80% more compliant than its predecessor and 24% more compliant than the Emonda. Those numbers are big, but keep in mind that neither the Gen 7 Madone nor the existing Emonda were known for their sofa-like ride qualities.

Further aiding comfort is the fact Trek brought the new Madone into the current age of tyre widths. Even in 2023, Trek was equipping its Gen 7 Madone with a dated 25 mm tyre width. Now the new Madone comes stock with 28s (measuring an actual 29.5 mm at 68 psi), and there’s officially room to fit 32 mm tyres (based on Trek’s generous 6 mm of surrounding clearance allowance).

New sizing

It wasn’t so long ago that Trek offered its race bikes in a choice of two fits, with H1 (pro race) and H2 (consumer) providing a choice in stack and reach figures. Eventually, Trek consolidated those into H1.5, with fit figures taking an approximate average of the two prior choices. Now, Trek has rebranded H1.5 to “Road Race” geometry. While the numbers are closely comparable to the previous H1.5, there are some significant differences to note.

Firstly, Trek is changing from its long-standing numerical sizing to alpha-type sizing (think T-shirt sizing). The size chart is now a close match to that of Giant Bicycles, with a 54 cm equating to a medium, a 56 cm being a Medium-Large, and a 58 cm being a Large.

If consolidating two race models into one wasn’t enough, Trek has also reduced its size range from eight options to six. One reduction comes by merging the previous 52 and 54 cm sizes into a single Medium choice. This may sound problematic, but those two previous sizes sat surprisingly close to each other with just a 3 mm difference in frame reach and 8 mm in stack. I personally had long thought I was between the 52 and 54 cm sizing, wishing for the reach of the 52 cm and the stack of the 54 cm, and seemingly, my wish has now come true.

The second reduction comes from Trek ditching its biggest 62 cm frame size option and merging it with the 60 cm to create the new Extra Large size. According to the company, this new biggest option has an even higher maximum saddle height than the discontinued 62 cm option while giving up just 10 mm in stack height (compared to the 62 cm size). I’ll never be tall enough to be upset by this, but it does feel like brands are increasingly ignoring the giants of this world.

Beyond these changes the fit numbers are close to where they previously sat. That said, the revised one-piece RSL Aero handlebar equipped on the SLR models adds an effective 4 mm to the stack due to its thicker shaping. Don’t want that extra height? Trek will offer a special “wow, you must be pro” (not its actual name) low-bearing top cover as an aftermarket option.

While lighter and easier to grasp with a thicker profile, that new one-piece RSL Aero handlebar otherwise features the same flared drops and dimensions as the version before it. That means these bikes are coming stock with an appropriately narrow-width handlebar at the controls, with options measuring as narrow as 35 cm at the hoods. Even the widest 44 cm handlebar (measured at the drops) measures a respectable 41 cm at the hoods. Trek will produce its RSL Aero handlebar/stem in an impressive 21 different length and width configurations, including stem lengths ranging from 70 to 130 mm.

Tech notes

Historically Trek has not done a stellar job of keeping consistent parts across generations of bikes. I can think of one Madone generation that used a unique headset bearing that has never been used since, while many other models have introduced proprietary headset top caps and seatpost-related things, to the chagrin of mechanics. Now Trek is making up for it with some big promises around ushering in a new generation of parts standardisation and interchangeability.

Perhaps at the forefront of that is the introduction of the Universal Derailleur Hanger (UDH) to its road race bike – maybe a first for the WorldTour. Trek had already introduced the UDH to its entry-level Domane AL road bike, and it’s now clear this will be the derailleur hanger of choice moving forward for its entire road, gravel, and mountain bike ranges.

Keeping with the drivetrain, Trek is sticking with its 85.5 mm-width T47 Internal threaded bottom bracket, and there is no shortage of options to fit that today. The Madone SLR is compatible with electronic gearing only, while the lower-cost Madone SL can be fitted with mechanical shifting. Both versions feature a removable front derailleur tab should you wish for a clean 1x gearing setup. Assuming a 43.5 mm-chainline crank is fitted, the new Madone can handle up to 43/56T gearing in a 2x gearing configuration, or a 54T chaining in a 1x.

In a slight departure from the norm, the new Madone is designed to take either a 180 or 160 mm front disc rotor (not 140 mm!), while the rear can handle a 140 or 160 mm disc. There are new thru-axles, too. The Madone SLR gets some fancy chamfered versions that sit inward of the frame dropout, while the Madone SL will have more typical bolt-up axles. Both versions come stock with a removable handle that also provides a few useful hex-key sizes.

The non-traditional seatpost design of course means a few proprietary features. XS-Medium sizes come with a short-length seatpost (150 mm) in a zero setback configuration, while the bigger sizes come with a longer-length seatpost (190 mm) in a zero setback. Of course aftermarket options for swapping lengths or going to a 20 mm setback option will be made available (in black).

All posts are held in place with a unique wedge system that securely locks the post via a single 4 mm hex bolt (tightened to 5.2 Nm). The securing hex bolt is accessible through the rear slot in the frame, and the wedge can be flipped depending on your required saddle height. That said, I did experience an unusual rattle in my test bike that I traced down to this wedge. Some grease hushed it, but I was somewhat surprised that such a multi-part chunk of aluminium would feature in such a weight-focussed machine.

That seatpost design also means users of Shimano Di2 need a different location for the battery. Here, the Madone offers a proprietary battery holder that bolts into the base of the down tube. It’s only accessible with the bottom bracket removed.

More goals of standardisation within Trek’s range come with the new RCS Headset system. There are three top cap and matched spacer variants applicable to the new Madone, all sharing the same 1.5" bearing and composite cable-guiding split ring beneath:

- RCS Race: Matches the new RSL Aero bar/stem (included with Madone SLR Gen 8)

- RCS Pro: Matches the current RCS Pro Blendr stem (included with Madone SL Gen 8)

- RCS Universal: For use with traditional round stems (regular 1 1/8-in. steerer clamp)

Complete bikes will ship with a generous stack of spacers below the stem; 40 mm to be exact. This is the maximum allowed by Trek, and I’d argue that those who need the full height should already be considering a model of bike with a more appropriate frame stack figure (such as Trek’s Domane).

Another detail many will appreciate is that Trek supplies an alternative top cap for the stem which allows the use of regular round headset spacers to be placed on top. As a result, you can freely adjust the height of the stem without having to undo brake hoses or cut the steerer (at least until you’re ready to). This seems like a simple feature, but it’s worrying how many integrated stem designs fail to offer such convenience.

There’s also a new computer mount to match the new RSL Aero handlebar on the SLR bikes. Provided with the Madone SLR, the new lightened but non-adjustable mount includes pucks for Garmin and Wahoo computers. It also combines with a provided universal mount for lights, which is easily removed via a single hex bolt.

Aero you can squeeze

Trek’s new RSL Aero bottles and corresponding cages form a key part of Trek's claim that the new bike is just as speedy as the old. Trek states these new bottles help smooth the airflow between the down tube and seat tube. A pair of them saves a claimed 3.7 W at 45 km/h (or 1.8W at 35km/h) compared to a pair of 600 ml round bottles in Trek Bat cages, and they’re claimed to be faster than using no bottles at all.

The new bottles are UCI-legal and the aero gains are enough that Trek states its men’s and women’s teams will be racing with them. Clearly, the cages and bottles were designed with the new Madone in mind, but the Wisconsin company states they also improved the aerodynamics of every other bike they tried them on, too.

Given the bottle's importance to the bike’s performance, the bottle's performance matters greatly. The bottles are offered in a single 595 ml (20 oz) capacity, are BPA-free, and are dishwasher-safe. The pull-top bite valve is not removable or replaceable. I found the bite valve a little tough to open, and the water flow to be acceptable but not rapid. An empty Aero bottle weighs a not-so-light 97 g. Thankfully, the matching carbon cages are a respectable 39 g each.

Taking a page from Cannondale’s book, the new aero cages can also hold any regular round bottle from the collection that currently occupies its own kitchen cupboard in your house. Carrying a regular bottle looks a little funky, but it at least holds it over a bumpy road. The fit with the Aero bottle is secure without being a pain to grab the bottle from, but there is certainly a learning curve in returning a non-round bottle to its holster.

Trek will offer its RSL Aero bottles in a smoke (black) colour or the pictured team blue. Matching carbon cages are available in black, white, and blue, with Project One bikes (excluding ICON paint) getting painted-to-match cages. Bottles and cages will be available for individual purchase, but expect to pay US$100 for a bottle and cage set (one bottle, one cage).

Madone SL vs Madone SLR

The new Madone, along with the Emonda's phaseout, represents a significant reduction in Trek's stock-keeping units (SKUs), with two bike lines becoming one, two fewer sizes across all models, and a narrower range of stock colour options. There are now nine complete bike options and two frameset options, split between the more-affordable Madone SL and the premium Madone SLR.

The Madone SL shares the same aesthetic exterior as the SLR but features a heavier 500-series OCLV carbon lay-up. All versions of the SL come equipped with a two-piece handlebar and stem (RCS Pro). Meanwhile, the fancy aero bottles and cages need to be purchased separately.

| Model | USD | UK | AU | EU (Belgium) |

| Madone SL 5 | $3,500 | £3,250 | AU$4,500 | €3,500 |

| Madone SL 6 | $5,500 | £4,250 | AU$6,500 | €5,000 |

| Madone SL 6 AXS | $6,000 | £4,750 | N/A | €5,500 |

| Madone SL 7 | $6,500 | £6,000 | AU$8,500 | €6,500 |

| Madone SLR 7 | $9,000 | £8,000 | AU$13,000 | €9,000 |

| Madone SLR 7 AXS | $9,500 | £8,500 | AU$14,500 | €9,500 |

| Madone SLR 9 | $13,000 | £12,000 | AU$19,000 | €13,500 |

| Madone SLR 9 AXS | $13,500 | £12,500 | AU$20,000 | €14,000 |

| Madone SLR 9 AXS P1 (Interstellar) | $17,000 | £14,700 | N/A | €16,400 |

| Madone SL Disc Frameset | $3,800 | £2,750 | N/A | €3,000 |

| Madone SLR Disc Frameset | $6,000 | £4,575 | AU$8,000 | €5,000 |

There are four complete Madone SL bikes in the 2025 range, starting with the Madone SL 5, the only model to feature mechanical shifting (Shimano 105 12-speed) and alloy rim wheels. The Madone SL 6 introduces 105 Di2 shifting and Bontrager Aeolus Elite 35 carbon wheels, while the Madone SL 6 AXS swaps to an SRAM Rival AXS groupset. At the top of the Madone SL range, the likely-to-be-popular SL 7 upgrades to Bontrager Aeolus Pro 51 carbon wheels, a carbon handlebar, and a Shimano Di2 12-speed groupset. This bike is claimed to weigh 7.88 kg without pedals.

The Madone SLR range kicks off with the SLR 7, running the same level of build kit as the previously mentioned SL 7. However, with a change in tyres and to the one-piece RSL handlebar/stem, this one carries a claimed weight of 7.31 kg. At an extra 100 g is the Madone SLR 7 AXS with a SRAM Force AXS groupset. And then we arrive at the flagship Madone SLR 9 and SLR 9 AXS options, offering a choice between Shimano Dura-Ace Di2 or new SRAM Red AXS. And finally, you get into the customisable world of Trek’s Project One, an option exclusive to the Madone SLR-level of bike.

As noted, all bikes come stock with 28 mm tyres – Pirelli P Zero Races for the Madone SLRs, and Bontrager R3 Hard-Case Lites for the Madone SLs. All but the cheapest Madone SL 5 bikes come with the tyres set up tubeless-ready, including the required tyre sealant.

Early thoughts

Let me preface this by saying that while I appreciated that the previous Madone existed, heavier aero bikes have never been to my liking or riding preference. And while I’d ridden many Madones over the years, I hadn’t yet thrown a leg over the Gen 7.

I had, however, ridden the most recent Emonda SLR. It was a fine bike, but like the Emonda before it, I still found the ride quality to be unnecessarily brutish without any obvious gain to performance. I understand some pro riders request a bike to have a stiff feel through the saddle, but I’m increasingly of the opinion that that's silly, and I at least know it’s not for me. Either way, the Emonda SLR wasn’t on my recommendation list, either. It’s fair to say that I came into a brief period of testing this bike with a decent level of scepticism.

Kudos to Trek – the new Madone has taken positive steps in making this platform more enjoyable to ride. The immediate sensation from the new Madone is that, while still stiff and certainly not muted to the road, it’s now far better-mannered in terms of seated comfort. The rear feels well balanced to the front, too, with a minor amount of flex in the RSL Aero handlebar doing the job there. And the wider tyre configuration (29.5 mm actual width) certainly helps greatly with that improved ride feel, too. There’s no denying the Madone is still a true race bike, but I at least find it to be an enjoyable one to be on.

There are also many other positives to the new Madone through what hasn't changed. The handling is still rapid but by no means a handful – it's a stable ride at speed. Trek's reach figures run marginally on the long side, but the company balances that with marginally shorter stem lengths for a given size, along with the narrowed bar widths, and now a zero-setback post as stock. And while I think the 40 mm stack of spacers given below the stem is excessive for such a race-focussed machine, it's at least a little more welcoming for those who strongly desire to be on a race bike rather than an endurance-styled road bike. Adding to this, the touch points remain comfortable, and the unchanged Bontrager wheels remain a solid option, with a quality hooked rim that keeps tyre choices wide open.

Early signs do point to the new Madone somewhat defying its ultra-modern looks by being a relatively simple bike to own. That seatpost design locks securely, and the independent saddle angle and fore-after adjustments are a nice change from Trek’s single-bolt systems of old. The ability to adjust stem height, or just access the headset bearings for greasing is nice. And it’s comforting knowing the UDH hanger means the frame is future-proofed for whatever SRAM is likely to cook up next.

Still, it’s not quite perfect. There is no additional sealing for either the top or bottom headset bearings. I’d like to adjust the (fixed) angle on the provided computer mount. And those aero bottles aren’t quite as easy-squeezy as the best round bottles.

Obviously, there’s a lot more to say about this bike, but a recent injury has left me in a position where I’d rather leave such further comments to my colleague Ronan Mc Laughlin. And while it’s a tough one to answer, hopefully, he’ll be able to provide further insight into whether the new Madone meets the company's speed claims.

Questions remain

Merging two race bikes into one is always going to be polarising decision and a risk for the company. I’d argue the new Madone isn’t as aero it could be, and equally, it’s certainly not the lightest bike Trek could make. Still, most athletes now demand a lightweight aero bike, or an aero lightweight bike, and there is an increasing amount of nuance in how you separate those demands. As someone who has never loved heavy aero bikes, or rattle-can lightweight rides, I can understand Trek’s decision to seek a happy medium.

Of course, the pessimistic view is that Trek’s bike line was incredibly bloated given current market demand, and Trek had previously said it would cut spending by 10% including through reducing its lineup. Trek hasn’t just halved the number of race bikes it ships around the world; it’s also found further efficiencies in fewer sizes and colour options. It’s all upside for Trek bike retailers, but I can’t help but feel Trek has achieved it by making trade-offs that will matter to some.

Early impressions suggest the new Madone Gen 8 is a great bike that’s well worthy of competition at the top level. In a similar vein to bikes like the Factor Ostro or Pinarello Dogma, it speaks to riders seeking a well-rounded race bike, and bonus points for doing it in a package that can’t be accused of being boring to look at. Still, I suspect riders who firmly sit in either the camp of wanting a bike on the UCI weight limit, or one that is aero-optimised to the limit, will be left wanting something different to what Trek now has to offer.

Did we do a good job with this story?