The return of the Tour de France to the Puy de Dome on Sunday for the first time since 1988 will conjure many memories. For Dane Johnny Weltz, it will be of joy for his stage win in that 19th stage. For Spaniard Pedro Delgado, it will be for good and bad – from the Probenecid doping scandal that was then engulfing him and for which he eventually escaped any sanction, to his overall victory in that Tour.

For Rupert Guinness, then reporting on his second of 31 Tours, it will be his memory of witnessing one rider’s race of survival, fighting to compete another day; that of American Jeff Pierce.

Covering the Tour de France as a journalist in the 1980s was a lot different to today. The worldwide web and the Internet did not exist. Reporters would write their stories on typewriters and or on notepads with pens and send them by telex machines or by dictation on the telephone.

In the 1988 Tour de France, midway through stage 19, 188km from Limoges to the Puy de Dôme, I had to abandon an accredited media car occupied by Irish journalists in a small village in the Massif Centrale to dictate an update on a ‘collect’ (reverse charge) telephone call to Australia from a small cafe.

It was a risky move. There was the real possibility I would not get into another car and reach the finish. But deadlines are deadlines, and a journalist is only as good as how they met their last deadline. After finding a phone in a small cafe and entertaining locals with my dictation by phone, I faced the task of trying to hitch a ride from one of the accredited cars as the race reached the village. One by one, they were all full. I quickly realised I was about to be stranded. Until I saw the very last vehicle in the Tour entourage, the voiture balai, or broom wagon.

In desperation, I stepped in front of it, waving my accreditation. The broom wagon is supposed to pick up riders who have had enough, not journalists without a ride. But I soon found myself seated alongside its French driver, Joel David, en route to the finish, but at a pace I did not anticipate; that of the tiring lone rider cycling in front of us, American Jeff Pierce.

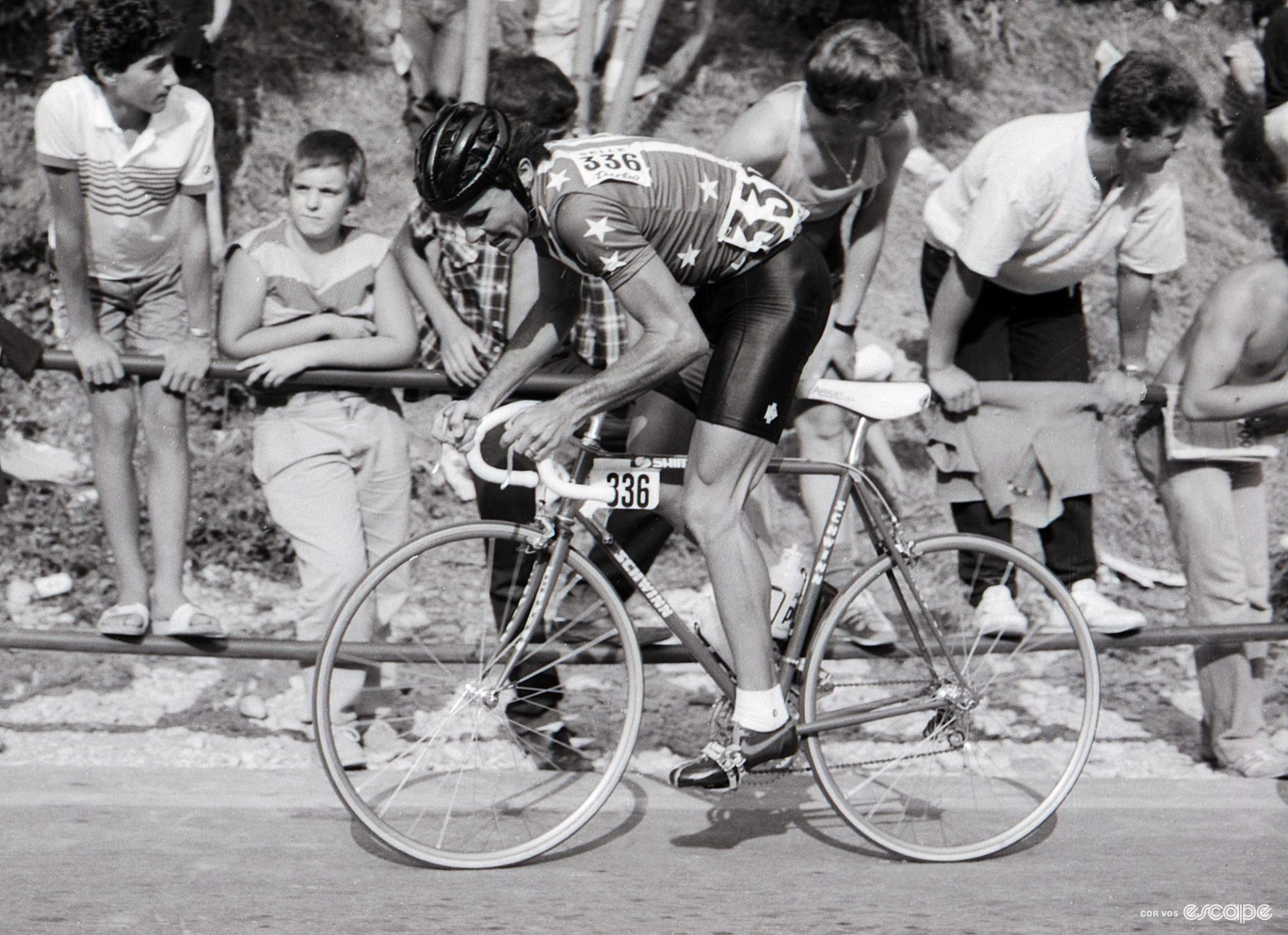

Pierce, on the 7-Eleven team, was a domestique, not a star, even though he had enjoyed Tour fame in 1987 by brilliantly winning the last stage into Paris. But now, that fame was a long way away. We crawled along behind him.

Pierce rode head down towards the Puy de Dôme that sat ominously on the horizon. At first glance, he looked remarkably relaxed. In reality, he was anything but. He was way off the back of the peloton, alone, struggling with his mind and body to finish the stage within the time limit and avoid the spectre of elimination.

Pierce’s demise began 30 km into the stage. He was dropped near the village of Cheissoux - his last energies had been sacrificed 10 km earlier to help his team leader, Andy Hampsten, re-join the peloton after crashing. By the time he came into my view, he was alone. The race had left him. His only company was a CBS Television crew, a 7-Eleven team car that sporadically returned from the race upfront to check on him, two members of the Garde Républicaine on motorbikes and us in the broom wagon. As Pierce’s margin to the peloton grew, it was clear he would not re-join it and probably finish outside the time limit. Riders in his situation have a choice. Fight to finish, or give up and jump in with Joel.

Despite the romance of such valour, those tasked with following the last rider tend to see the picture rather differently. Joel David made that clear from behind his wheel in the broom wagon. He had seen what was unfolding before us all too many times. Pierce was cheered on by fans packing up their picnic baskets, astounded to see a Tour rider still on the course. Joel offered little enthusiasm, but reasoned: ‘He will continue. It would be better for us if he abandoned, but for him, if he can finish, he will. Elimination is far better than giving up.’

Joel’s frustration festered as we continued slowly behind Pierce. I drifted in and out of sleep. And I admit, I was relieved when the Puy de Dôme neared and Joel told me the press room was at its foot and that he would take me there before following Pierce 13km to its top.

Pierce eventually rode on to be the last of 154 riders to cross the finish line (five others did not finish.) But, sadly, his courage and dogged spirit were not enough. He was the only rider to finish outside time limit, finishing 53 minutes 18 seconds behind a victorious Jonny Weltz.

Pierce’s fate was not unique. It happens every year. Last year, Fabio Jakobsen spent days on the very edge of elimination. He looks set to do the same this year. Watching it unravel reinforced the so tenuous fate of a rider in the Tour. Jeff Pierce had gone from being a celebrated stage winner in Paris one year earlier to being a rider whose name would be summarily scratched off the starters list for stage 20.

The Tour. It can be so giving, yet so unforgiving too.

Did we do a good job with this story?