A strong performance at a race like the Tour de France isn’t just about riding well day after day for three weeks. It’s also about recovering well from each of those day’s exertions, allowing the strong performances to continue right through to the end of the race. And when it comes to recovery, nothing is more important than good sleep.

With that in mind, what does good sleep look like for a rider in a race like the Tour? How late are riders going to bed, how much are they sleeping, how deeply are they sleeping, and does the cumulative effect of weeks of hard racing end up degrading a rider’s sleep?

An international research team recently set out to answer these questions in a study that’s now published online in the journal Sports Medicine – Open. And they didn’t just focus on male riders from the Tour de France; they also considered female professionals racing the Tour de France Femmes too.

The basics

In all, 17 professional racers took part in this research project. Eight male riders from the same (undisclosed) team at the 2022 men’s Tour de France; the other nine split across two women’s teams (also undisclosed) at the 2022 Tour de France Femmes.

Data for the study were collected using WHOOP 4.0 wrist-worn fitness-tracking devices. Like a handful of similar devices on the market, WHOOP tracks an individual’s heart rate and other metrics to see how much strain they're under and how they’re recovering – including how well they’re sleeping.

Each rider’s sleep was tracked in the week leading up to the Tour (to create a baseline), during the race, and in the days afterwards. For each sleep, the following variables were recorded:

- what time the rider went to sleep

- what time they woke

- how long they were in bed for, in total

- how long they actually slept for

- their sleep efficiency (the percentage of their time in bed that was spent asleep), and

- how much time they spent in different sleep phases.

The three sleep phases considered here were:

- Light sleep: The transitional state between being awake, and deeper sleep.

- Slow-wave (or deep) sleep: The phase responsible for muscle repair and growth.

- Rapid-eye movement (REM) sleep: The mentally restorative phase of sleep.

Also collected for each rider were:

- their resting heart rate

- their heart rate variability (HRV).

HRV is a core metric for the WHOOP system (and others like it). It shows the average time difference between heartbeats and, in the words of the researchers, “can be used to quantify the acute stress-recovery responses of the autonomic nervous system following a bout of exercise.”

More specifically, a higher HRV – that is, greater variation in the time between heartbeats – is believed to show the sympathetic (“fight or flight”) and parasympathetic (“rest and digest”) branches of the nervous system simultaneously sending signals to the heart. As per the WHOOP website: “If your nervous system is balanced, your heart is constantly being told to beat slower by your parasympathetic system, and beat faster by your sympathetic system.” These greater fluctuations are a sign of a body that’s primed and ready to perform at its best.

The researchers also collected data on each rider’s physical workload and strain during each stage of the race, but these findings, in truth, turned out to be less interesting than any of the sleep-related data.

The researchers also note that while the study began with eight riders in the men’s race and nine in the women’s, they didn’t have that full cohort by the time the races ended. Of the eight male riders, two withdrew during the race, while on the women’s side, eight of the nine completed the Tour.

The male riders were also seemingly a little slacker than the women – while all women wore their WHOOP on every day they raced, there were several days of the men’s race where some riders opted not to, for reasons that aren’t disclosed. Most striking of those days is the final stage where only three of the six remaining participants wore their WHOOP strap.

We’ll come back to that final stage. But first, some results.

Results from the male riders

To put the race data into some sort of context, let’s first look at what the baseline testing showed in the lead-up to the men’s Tour. During this baseline period, the participating riders, on average:

- went to sleep at 10:03pm

- woke up at 6:21am

- spent 8.3 hours in bed, getting 7.2 hours of sleep

- had a sleep efficiency of 87% (i.e. 87% of their time in bed was spent asleep)

- spent 45% of their sleep in light sleep, 18.5% in slow wave sleep, and 23.4% in REM sleep. (For context, averages for non-athletes of a similar age are 54.8%, 16.3%, and 20.7% respectively)

- had a resting heart rate of 41.8 beats per minute (that’s around 54 for non-athletes)

- had a HRV of 108.5 ms (82.9 for non-athletes).

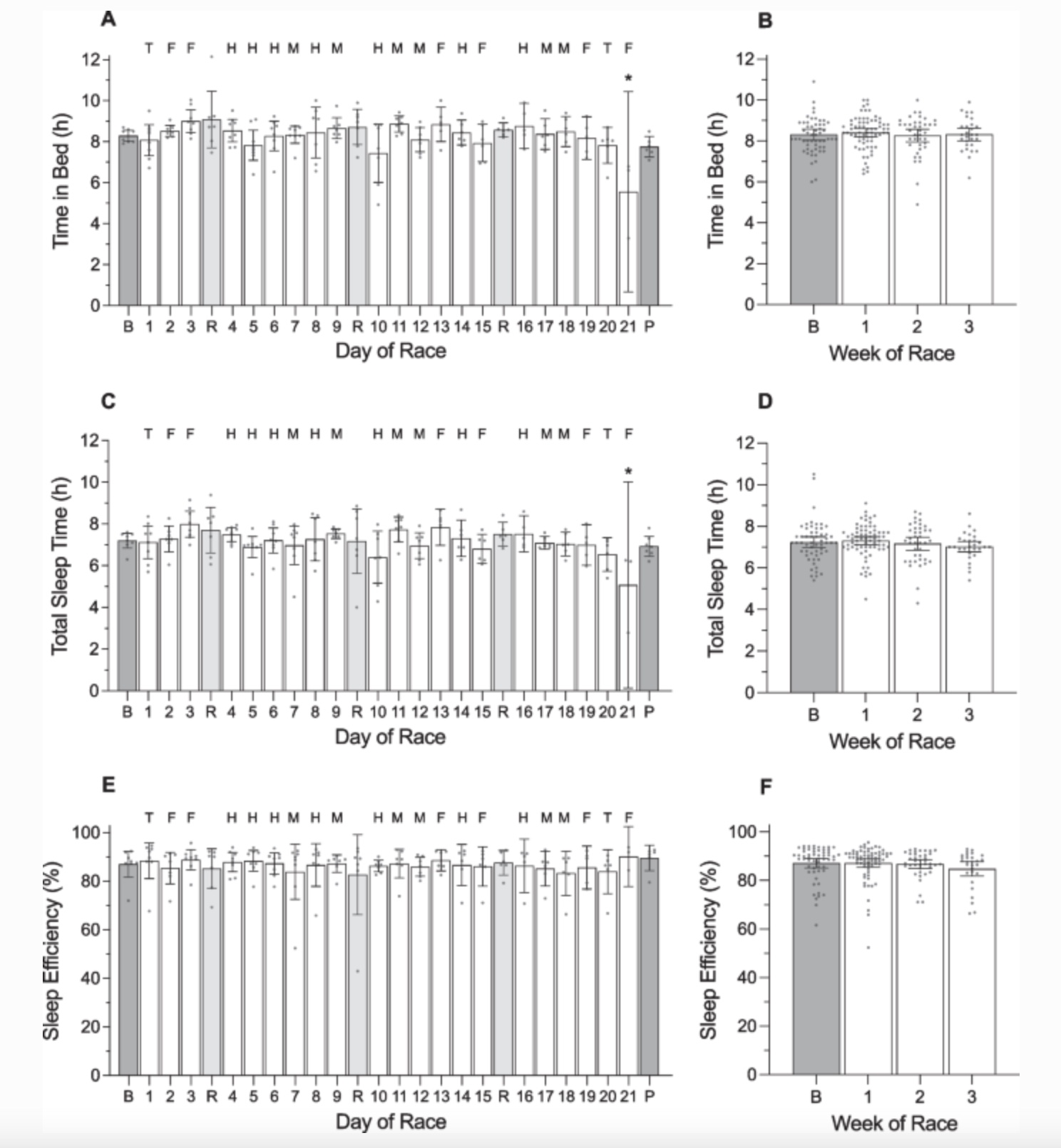

And here’s what those metrics looked like, averaged across stages and riders, when gathered during the Tour:

- the riders fell asleep slightly later, at 10:20pm

- they woke a little later too, at 6:36am

- they spent slightly longer in bed – 8.4 hours vs 8.3 – and averaged 7.2 hours of sleep – the same they did pre-race

- their sleep efficiency was basically the same – 86.4% in the race, 87% during the baseline testing

- they spent more time in light sleep (49.5% vs 45%), had slightly less slow wave sleep (17.3% vs 18.5%), and had quite a bit less REM sleep (19.6% vs 23.5% pre-race). These changes point to slightly less restful sleep as a result of significant exertion.

- Resting heart rate was elevated throughout the Tour (44.5 bpm vs 41.8 bpm)

- heart rate variability dropped from 108.5 during the baseline period to 99.1 during the race.

If we dig a little deeper into the charts containing each day’s data, there are a few notable takeaways:

- The amount of time riders spent in bed was pretty consistent throughout the Tour, but did drop slightly towards the end.

- The riders didn’t spend noticeably more time in bed on rest days than race days, perhaps with the exception of the transfer/rest day after stage 3 (from the Grand Depart in Denmark to France). But even then that average was skewed by one rider seemingly having more than 12 hours in bed that day. Curious.

- There was another outlier on stage 10 – one rider had only four hours of sleep, from five hours total in bed. That’s rather curious as well, and brought down the sleep time average of the whole cohort for that stage.

- Riders seemed to get slightly less sleep in the block between the final rest day and the end of the race.

- Average sleep efficiency dropped a little in that final ‘week’ as well.

- The percentage of slow wave sleep was quite variable throughout the race, and REM sleep was even more variable. From a baseline of 23.4%, this dropped to as little as 15% on some days.

- Resting heart rate didn’t change in a meaningful way throughout the race.

- There were some increases in heart rate variability on all the rest days, and then the day after the Tour finished. This shows the riders’ bodies getting a chance to properly recover after an easier day.

And then there was the final stage of the Tour; a twilight sprint on the Champs-Élysées. The data from this day is one of the most intriguing parts of the entire paper.

While six of the original eight riders remained in the race by the final stage, just three wore their WHOOP strap on the day and night of that final stage. Those that did painted an interesting picture. On average, those riders went to sleep considerably later that night than on any other night of the race (just after 1am on average, vs roughly 10:20pm), they spent significantly less time in bed, and they slept far less.

The later finish to the stage will be a small part of that – the 7:45pm finish was several hours later than any other stage – but the bigger factor here is the post-Tour celebrations that most riders indulge in after finishing a Tour de France. This might be a simple dinner with their teammates and team staff but, for a certain percentage of the peloton, it might also include a Parisian nightclub and a night that ends in the small hours.

One of the three riders who wore their WHOOP strap the night of the final stage in 2022 seems to have had a longer night than others, getting less than three hours’ total sleep. The other two riders got closer to six, but the one night owl among them affected the cohort’s average. These results from the final stage were excluded from some of the researchers’ analysis but as we’ll soon discuss, the impacts of having such a small study cohort shouldn’t be overlooked.

Results from the female riders

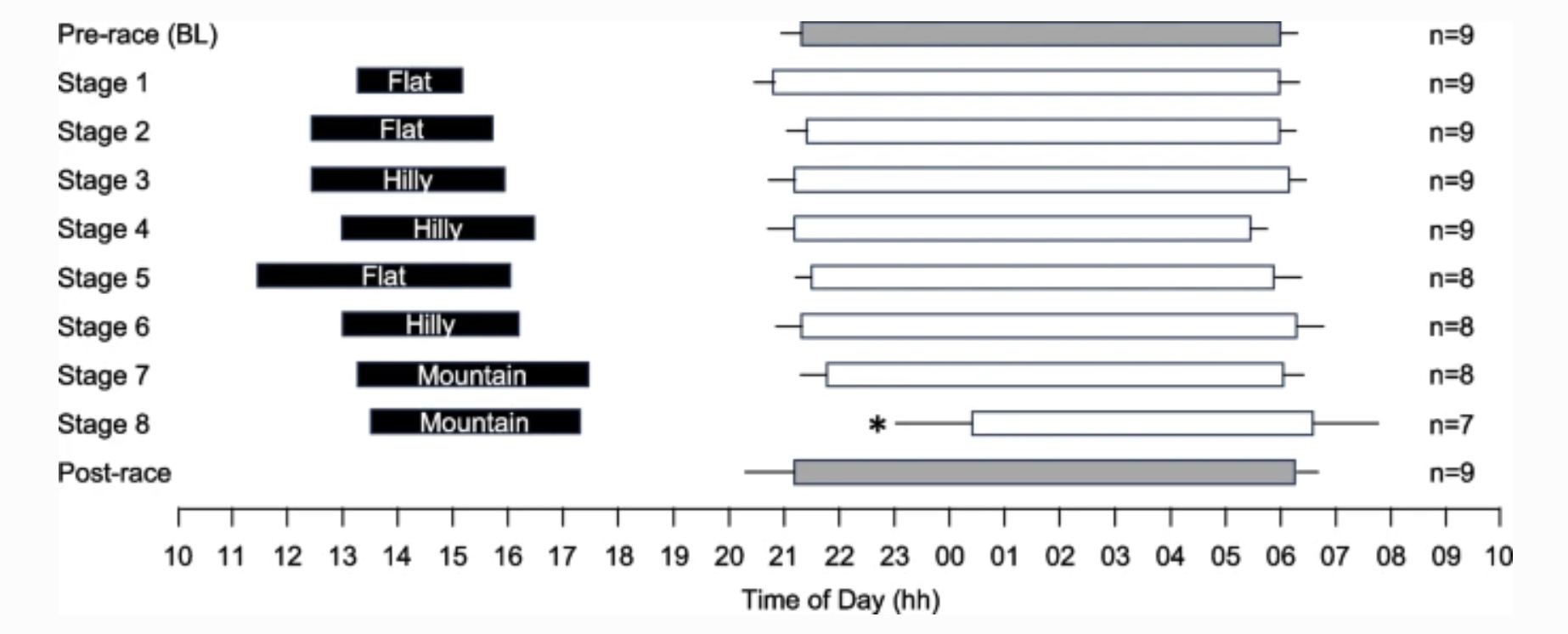

As we did with the male riders, let’s first look at the baseline testing period for the Tour de France Femmes riders. On average, in the week before the race, the female riders:

- fell asleep at 9:18pm (earlier than the men)

- woke at 5:58am (also earlier than the men)

- spent 8.7 hours in bed for a total of 7.7 hours sleep (both longer than the men)

- had a sleep efficiency of 88% (much the same as their male counterparts)

- spent 41.9% of the time in light sleep, 20.2% in slow wave sleep, and 26.7% in REM sleep (by way of comparison, that’s more slow wave and REM sleep than the men’s baseline readings, with less light sleep – seemingly indicative of more restful sleep in general)

- had a resting heart rate of 45.8 bpm (just higher than the men)

- had an average HRV of 119 ms (around 10 ms higher than the men).

Here’s how those numbers looked during the race, on average, across riders and stages. The study participants:

- fell asleep at 9:37pm (later than pre-race)

- woke at 6:03am (a little later than pre-race)

- spent a little less time in bed (8.4 hours vs 8.7 hours) and slept less overall (7.5 hours vs 7.7 hours)

- had slightly more efficient sleep (89.6% vs 88%)

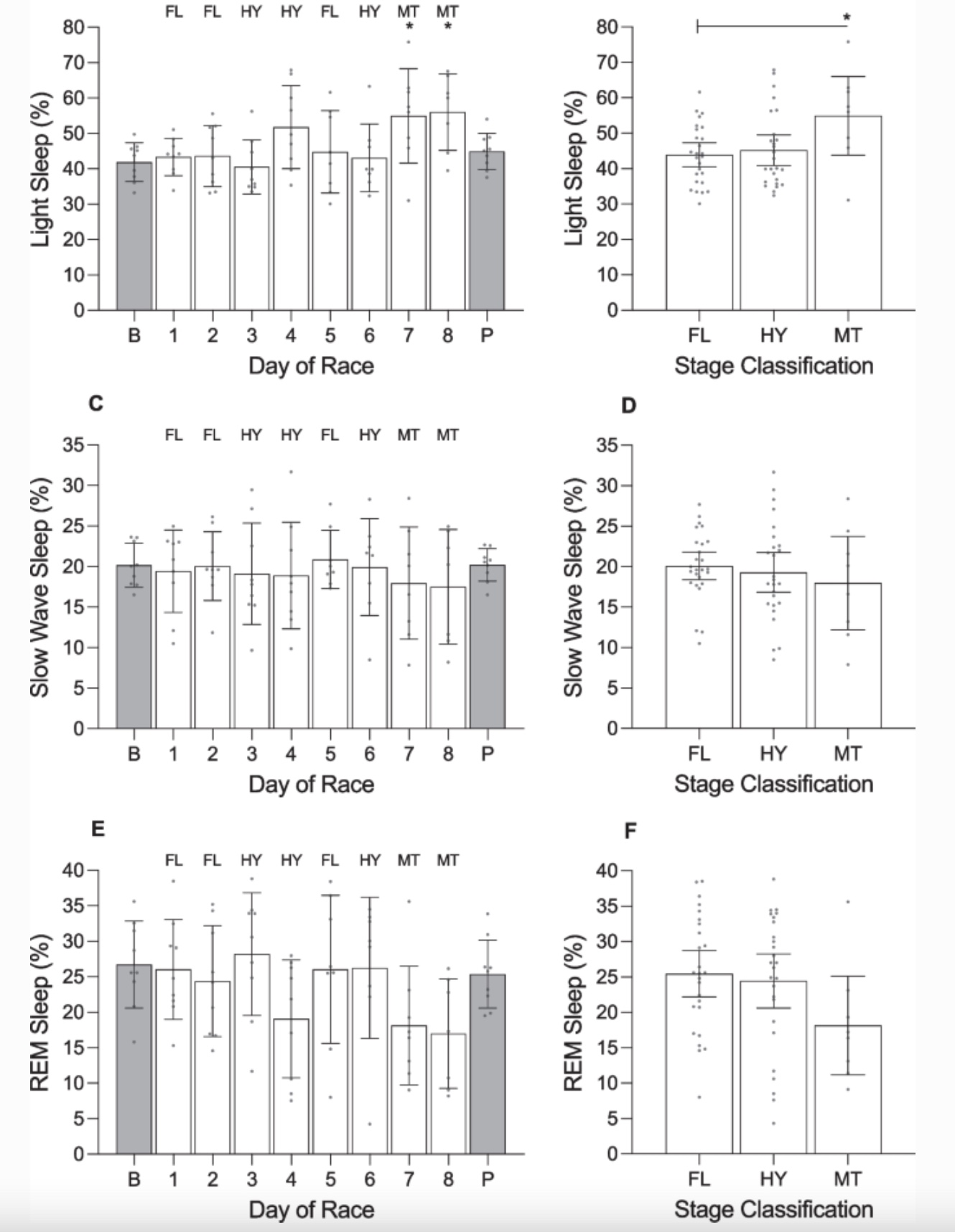

- had more light sleep (47% vs 41.9%), less slow wave sleep (19.3% vs 20.2%), and less REM sleep (23.2% vs 26.7%). As with the men’s cohort, these changes represent a reduction in deeper, restful sleep, which makes sense.

Drilling down into the data, there are some more specific findings to take note of:

- The female riders’ light sleep percentage was notably higher on the race’s two mountain days, again likely showing the effects of greater exertion.

- Similarly, less time was spent in REM sleep during the mountain stages, but also after the gravel stage, stage 4, where two riders had just 5-10% REM sleep for the night.

- As with the men, resting heart rate was elevated during the race compared to baseline, and most notably on mountainous stages.

The female cohort also logged far less sleep after their final stage than at any point in the race – an average of six hours in bed for around 5.5 hours of sleep, compared to 8.4 and 7.5 hours on average across the race.

As with the men, post-race celebrations likely played the biggest role here, but travel plans might have also had an impact, with some riders looking to get home immediately post race, with all of the sleep disruptions that such travel can entail.

Concerns

You’ve probably already noted some issues with this research, not least the small sample size of the study cohort. With as few as three riders providing data for one of the men’s stages, and only a maximum of nine riders for the women’s race, this is far from a complete picture of the entire peloton. That’s significant because, as noted above, whenever one rider is an outlier in a given metric, the average for the cohort is skewed significantly, which throws into question the validity of the results.

Ideally, the entire peloton would participate in a study like this. But as the researchers seem to have found, it’s hard enough getting nine riders to take part for the entirety of the Tour, let alone an entire peloton. And that’s to say nothing of the sponsor conflicts that would surely prevent some riders from using a device like WHOOP.

The authors also note that their study doesn’t do anything to differentiate between the different roles that riders have on a team, and how that might affect the findings. For example, on a flat stage of the Tour, a domestique who rides the front of the bunch all day for their sprinter, is going to have a much harder day than their GC leader who’s safely ensconced in the bunch. Averaging the exertions of these two riders in the same (small) dataset will almost certainly paint a distorted picture of how racing the Tour impacts sleep.

The riders’ use of supplements, caffeine, alcohol, or medications, or any naps they took, also weren’t factored into the study. All of these could have an impact on an individual’s sleep on a given night, again skewing the results from the small dataset.

Takeaways

With all those caveats, what can we make of this research paper? Here’s how the researchers sum up their work:

“The results of the present study indicate that some aspects of recovery were compromised in cyclists after the most demanding days of racing, i.e., mountain stages. Overall however, the cyclists obtained a reasonable amount of good-quality sleep while competing in these highly demanding endurance events.”

The authors note that they were surprised to discover that “total sleep time in the present study was not influenced by consecutive days of racing and remained relatively stable across most nights of the race”. As a reminder, the male riders averaged 7.2 hours of sleep both before and during the Tour, and the female riders only dropped from 7.7 to 7.5 hours per night.

That in itself is interesting. It’s also not really comparing apples to apples. Life on the road at a bike race is very different to at home, where family commitments and other responsibilities come into play. For those racing the Tour, an almost monastic focus is possible. Racing and recovery is paramount, and the riders have the time and space to sleep for as long as they need. The same isn't always true at home.

Related: the 7.2 hours (male) and 7.7 hours (female) of sleep that the Tour riders got as a baseline, is nearly one hour longer per night than elite cyclists get in a normal phase of training. As the authors point out, “it is very likely that the cyclists prioritised sleep over other activities” in the lead-up to the Tour, what with it being the biggest race of the year and everything.

As noted, this study isn’t without its flaws, and all of the results above should be viewed with a certain degree of scepticism. And yet, these findings still give us something of a glimpse at how the world’s best riders approach sleep at the biggest race of the year, and how that race affects sleep.

If I’m honest though, what I really want to see is a full peloton's worth of data from the post-Tour celebrations. How many riders head out for a massive night, and how many take it easy? And how many don't sleep at all after the final stage?

Did we do a good job with this story?