In the bunch rides and club criteriums of Australia, there’s a change afoot. Alongside the shop-team kits and expensive MAAP and Rapha ensembles, there are glimpses of outfits that are jarringly familiar: a Jumbo-Visma kit here, a Quick-Step kit there. But these aren’t pros on an off-season sabbatical – they’re amateur riders sporting team-issue gear that was previously worn by pros, and they don’t care what you (or Those Stupid Rules) think about that.

How that kit got into their hands is an interesting and unlikely journey, beginning in the wardrobes of WorldTour pros, via an ‘agent’ in France, to a Yorkshireman in Perth, Australia, and from there to consumers on the hunt for pro kit.

That Yorkshireman – Escape Collective member Paul Braybrook – is currently a lecturer in paramedicine, but before that he worked as an environmental scientist, where he developed a passion for recycling and extending product life. Simultaneously, he’s an enthusiastic cyclist, and a year or two back, idly started collecting pro-team kit. “I was a huge EF fan, and I was always hunting down hard-to-get pieces … the bits that you can never buy from Rapha – like the long sleeves, and the gilets, and the rain jackets,” Braybrook told me.

And where can you get them from if they’re not commercially released? Straight from the source. “I would contact riders who had moved team or maybe had retired, trying to get them to sell me some stuff. But the problem is the more I did it, the less they wanted to sell just a jersey or a piece of kit, because it’s a lot of effort for them to go to for a $50 jersey. In the end I’d just say to them, ‘hey, if you want to sell me all your kit, I’ll just take everything you've got.’”

Braybrook would grab the items he wanted, and flip the remainder. Then came a realisation: perhaps there was a business in it. Spurred on by a friend, Quick-Step was next in his sights – “I approached some Quick-Step riders, got a really good response, got all of the kits and it sold really quickly, really easily.” Unexpectedly, there was also a secondary realisation: his customers were thrilled to have access to top-tier kit from the teams they supported. “They were just so happy – just so, so happy,” Braybrook explained. “We’d get all these messages from people – ‘thank you so much. Now is there any chance you could get something from this other team?’”

Things quickly snowballed: one rider would make an introduction to another, “and then suddenly we made all these contacts from these riders that were really keen. Everyone was just super happy, because they would get rid of these boxes of kit sitting in the garage,” Braybrook continued. “I had a message from a rider’s wife to say ‘thanks so much for getting rid of this, they’ve just been sitting there and I’ve been onto him for months.’”

It was a win-win-win: “the riders were really happy ‘cos they got a nice little cash bonus at the end of the year, I was happy because I was getting kit and then our customers were just so stoked to get this stuff.” The business continued to take shape as Braybrook and his wife honed their processes: working out what to do with damaged kit, and working out how to remove road grime or sticky glue from race numbers.

Braybrook’s wife, who is French, was an invaluable part of the business’ expansion: firstly, by tapping into the French market and building connections with the likes of AG2R and Groupama-FDJ; secondly, through enlisting her mother as a forwarding ‘agent’ in Europe; and thirdly, through her skills on the sewing machine. “Her granddad was a tailor, her grandmother was a seamstress, so she’s really skilled with a sewing machine. Meanwhile, I’m coming from the environmental background: I hate the idea of this stuff getting thrown away, like skinsuits that have been worn once.

"It’s the glue from the race numbers that’s the problem – there’s no way those numbers are coming off in a race, it’s just ridiculous,” Braybrook said. “So I spent ages working on this formula, basically like a citrus oil/alcohol mix, which degraded this glue. Suddenly a kit which was almost unsellable has been restored almost back to new, because they get used for a single race.

"Having this environmental background and working in commercial waste reduction, I was like, ‘this is so good’. We can take things that would be getting thrown away or will be of no use to anyone, and we can completely put them back into use.”

Braybrook registered the business mid-this year, under the matter-of-fact business name of ‘Pro Cycling Kit Sales’, and its customer base progressively grew, with customers from Melbourne initially leading the charge. “I’ve got this great photo – it’s like Jumbo, Jumbo, AG2R, Uno-X, and they’re all in this four-man break in a local crit. And they’re all independently my customers,” Braybrook said, grinning. “There are so many elements to this which makes me happy, and brings me so much joy. Seeing these race suits racing again is awesome … and it’s not a transactional relationship, where you’re like ‘here’s my money, give me my thing’. We just get constant messages, people say ‘thank you so much’.”

There are a number of factors, Braybrook suspects, at play in the response to his business. One of those is a thawing of the stuffiness around road cycling norms, most infamously defined by the Velominati (Rule #17, if you must reference that gatekeeping BS). “That was always something in my mind and put me off doing this initially – this perception that no one will wear this because you’re not allowed to wear it, right?,” Braybrook told me. “And I just haven’t encountered that at all: people do not care.

"I’ve discussed this so many times, and it’s this generational shift underway – those in their 20s, early 30s, not only do they not give a shit about the rules, they actively rebel against them.”

There's undeniable cachet to some of the kit, too – some of which can quite easily be identified as having once belonging to well-known riders – although Pro Cycling Kit Sales doesn't directly disclose past owners.

At the same time, the prices of kits from mainstream brands – the Raphas, the MAAPs and Pas Normals of the world – are skyrocketing. A pair of bibs and a jersey from Rapha’s Pro Team collection is currently AU$630; there’s no getting around the fact that it’s an expensive sport and becoming more so. At a point – and we’re probably some way past that – that becomes counterproductive to cycling’s growth.

“I think eliminating gatekeeping is so important,” Braybrook said passionately. “I hate the snobbery in cycling. Like yeah, you want to be able to ride and wear good kit, but wait, first you need AU$600. But then you also have people saying, ‘ah, but you can’t wear that kit, you can’t do that.’ We make it so hard for people! No wonder people are like ‘doesn’t matter, I’ll find something else to do, bye.'”

Meanwhile, Braybrook said, “we can offer [our customers] pro-level kit which is always the top level of whatever range it happens to be in, for a quarter, a fifth of the price – some used, but even brand new items. The bits of kit we repair are often sold for under AU$30, and bought by people for use on the trainer or in more crash-prone disciplines like MTB or gravel, which is a great way to get a second life for them and save your ‘best’ kit from getting trashed.”

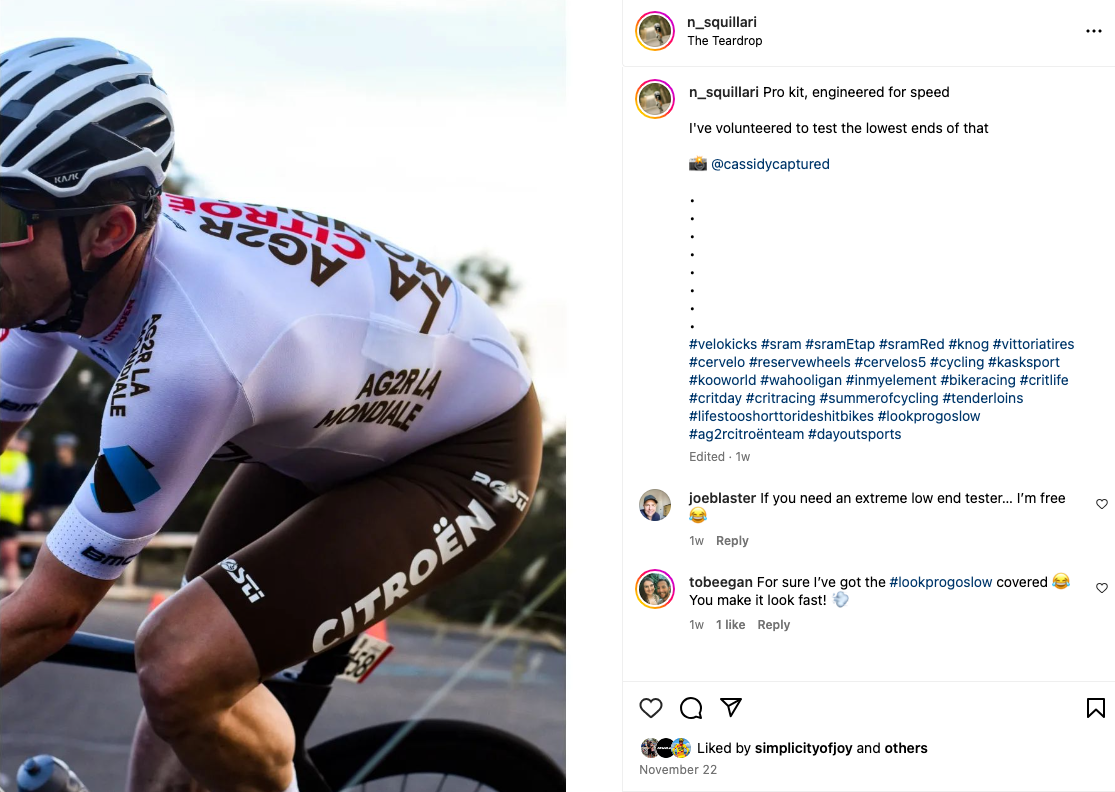

One of his customers, fellow Escape Collective member and known Melbourne hitter Nick Squillari, told me that price is a factor in his purchases, but he also has an ideological support for what his purchase represents. “I would love to see pro teams have more of a cachet around their branding and have the same desirability that football teams can bank on when it comes to merch sales,” Squillari said. “To see something like [NBA or Real Madrid] jersey sales – hell, even the NFL got a massive jersey bump when Taylor Swift started dating Travis Kelce … to see something like that for pro teams as a way for them to generate some revenue of their own – a battle they’ve been having as long as I’ve been watching cycling – would be terrific to see.”

That shift doesn’t happen overnight, but a social momentum can build.

Not every deal Braybrook makes with his growing network of 70 pro cyclist suppliers is a good one – pro cyclists are small, and he’s been burnt with XXXS kit that will prove stubbornly hard to shift. But he’s progressively learnt to target medium-sized riders to get the best chance of finding an eventual buyer, and part of his business model is in making the transaction simple for the cyclists: “we won’t mess you around and cherry-pick the high-profit items; we just take everything in one go, priced accordingly.”

The real, joyful stuff is the team casualwear: “the Bardiani velour tracksuit … that is just delightful,” Braybrook said with a smile. “And the AG2R denim shirt, with brown leather, elbow patches … the French teams love a team-issue jean.” I asked him if he’s ever going to sell the button-up Cofidis shirts currently in the store. “That is never selling,” he confirmed, laughing.

But enough of it is selling that with each of Pro Cycling Kit Sales’ monthly drops, the business gets closer to getting into the black. “I’ve totalled up what I’ve paid riders in the past six months for second-hand lycra, out of my mortgage, and it’s AU$158,000. On used lycra,” Braybrook said, matter-of-factly. “I reckon by the end of the year, we should be getting close to a zero balance, and we’ve got all these kits in now to last us basically until June, July.” If he keeps doing right by the riders, he hopes that will keep on rolling over, year after year.

While there’s a business and money on the line, it’s clear that for Braybrook it’s a bigger project that combines multiple passions – cycling, sustainability, family, reducing barriers. And at its core, there’s just a guy who loves a cool – sometimes ironically cool – pro team kit. “Absolutely I cherry-pick,” he admits. “I’ve got a Bingoals Pauwels Sauces kit I rode across France in … we need more sauce manufacturers sponsoring cycling teams. These are the wholesome sponsors we need! Like, you're riding around in a Belgian mayonnaise and ketchup sponsor, in a luminous yellow kit. That's outstanding! What is there not to love about that?!”

And does he have a single favourite item? A pause for a moment. “Here’s my litmus test: I say to people, ‘I’ve got Burger Bibs’, and if they’re like ‘woah, are you serious?!’, I know we’re going to be friends.”

Paul's top tips for maintaining your kit

'From someone who sees a lot of kit that gets treated badly:

- Modern kits degrade. Anything with a silicone gripper must be turned inside out or it fuses together

- Wash at 30 ºC

- If you tumble-dry your kit, the logos will absolutely crack and delaminate from the kit, making it look really old (I'm looking at you Rapha and Castelli), so avoid this at all costs

- Don’t spin at 1,200 rpm – this stretches and deforms kit, so try to spin at a lower speed

- Avoid leaving it in the direct sun for too long as a lot of the bright colours become faded easily

- Always wash with the zips done up to avoid them catching on other items and causing nicks.'

For more, see ProCyclingKitSales.com.

Did we do a good job with this story?