The dust hasn’t even settled on the cobbles of Mons-en-Pévèle when the peloton turns its focus east, to the steep, sinuous roads of the Ardennes. The cobbled Classics and the Ardennes races sit side-by-side on the calendar, but are distinctly different races.

Both the Tour of Flanders and Paris-Roubaix sport relatively flat profiles. Even though Flanders conjures up images of the Koppenberg, Oude Kwaremont and Paterberg, the race has an almost pan-flat opening of 130 kilometres before packing its punchy climbing into the final half of the race.

By contrast, the Ardennes manage to squeeze a remarkable amount of elevation out of some fairly modest terrain. The short and punchy climbs of the Ardennes, straddling Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg, are a world away from the longer Alpine ascents of Il Lombardia, the final Monument of the season.

Somehow, Amstel Gold, Flèche Wallonne, and Liège-Bastogne-Liège all manage to find more than 3,000 metres of climbing across their courses, with Liège sitting above the rest at 4,365 metres, or around 90% of the climbing found at Il Lombardia, also comparable to Grand Tour major mountain stages. All that across climbs that are far shorter, typically taking riders just 2-6 minutes to ascend.

These characteristics make the Ardennes perfect for riders with super high VO2max and otherworldly fatigue resistance. Not all races can be boiled down to a simple expression of W/kg, but in the case of the Ardennes, especially the 2025 editions, this goes most of the way toward explaining how to go about winning one.

Ben Healy’s Amstel Gold Race

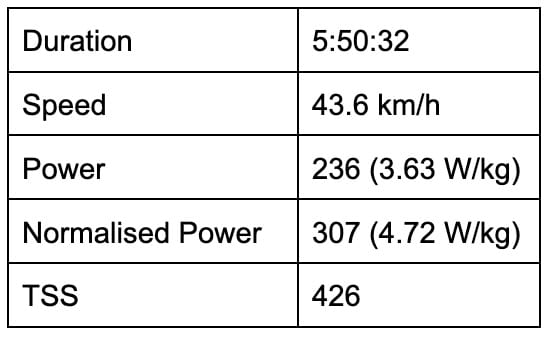

If you were to look at the top-level stats from EF Education-EasyPost's Ben Healy, considering his 10th-place finish, nothing screams otherworldly performance. It is by no means anything that someone outside of the WorldTour would be capable of, but it doesn’t tell the whole story.

Healy’s peak 20-minute power of 314 watts is 46 watts below his FTP, suggesting Amstel isn’t the hardest race in terms of sustained power. But that isn't what these races are about.

One small detail begins to point out what makes Amstel so tough. The delta between his average and normalised power is a chasmic 81 watts. In any ride, this is a significant difference, but for a race nearly six hours long, this is extraordinary.

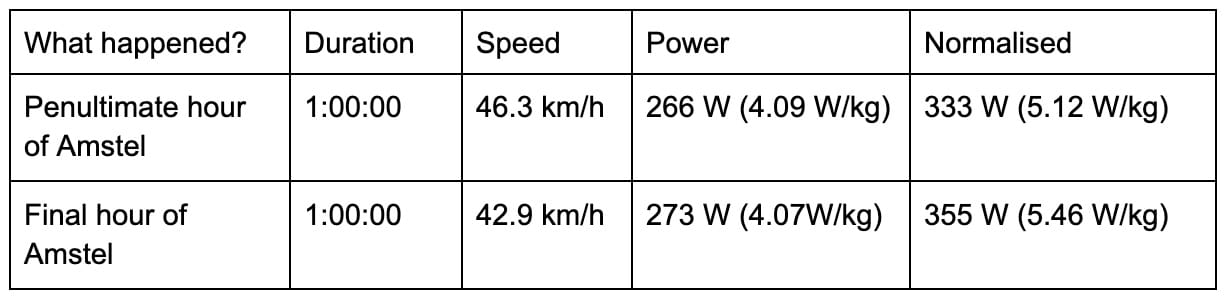

Healy's normalised-to-average power delta is because Amstel's parcours does not facilitate continuous high-power efforts. Short, punchy climbs – most of them under a kilometer in length – are separated by technical, fast descents. Healy’s peak 20-minute power comes at 4:39:52 into the race, and although the 314-watt average is nothing to write home about, the 395-watt normalised power is.

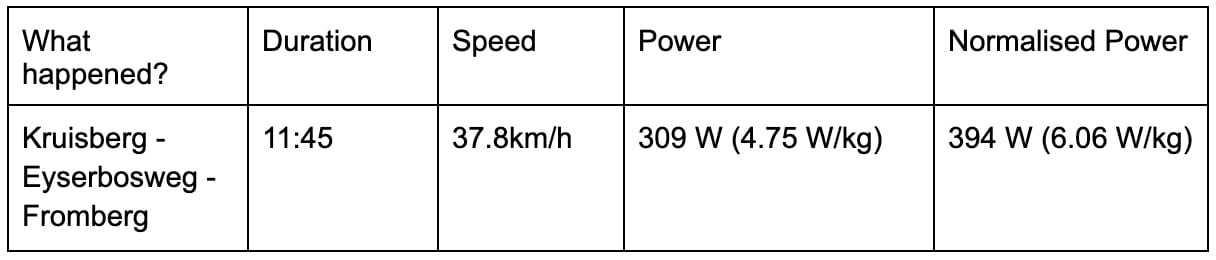

At around 220 kilometres into the race, the triple whammy of the Kruisberg/Eyserbosweg/Fromberg was tackled, and this shows exactly what it takes to be competitive at Amstel. Healy’s 499-watt peak over two minutes shows the race intensity when it is on, with just a 20-second rest period during the descent.

The graph from Healy's Strava file shows just how punchy this three-pronged combo was. Each climb is separated by crucial moments of freewheeling. It was either max effort or desperately trying to recover before the next round through this section of the race.

Did we do a good job with this story?