Long before he was a professional racer, Svein Tuft lived a life of pure adventure. In this extract from his autobiography We Will Never Be Here Again, which is written with Richard Abraham and currently crowdfunding on Kickstarter, we explore gravel bikepacking as it was in the 1990s. Step inside a world of home-made trailers, woollen blankets, Sony Walkmans, and chocolate milk as we travel with Svein on the road to Alaska.

I had accepted that I might die. The cold soaked through to my bones. I was out in the wilds of northern British Columbia, on the side of the Yellowhead Highway, in minus 10 degrees with a wool blanket and a tarp wrapped around me. Two fires were built on either side. I was coughing from deep down in my lungs, heaving in and out with the cold dry air. My body was giving up.

It was April and conditions had been cold and wet for weeks, but now the temperature had really started to drop. Sixty kilometres of total wilderness lay between me and the nearest settlement. And I was suffering. What had started as a cough had got down into my lungs and become pneumonia. My stubborn need to keep on pushing was finally verging on being too much. I had no resilience left. I sat there with my fires and realised this is what it could feel like. The end. I didn’t know if I would make it through the night.

I wasn’t a tough guy but I wasn’t scared. I was free of those thoughts. I didn’t have a device with all the answers in the world at my fingertips; had I known what I know now, I would have been pretty freaked out. What you believe has a lot to do with what happens in your body, and not knowing stuff is one of the most beautiful ways to go through life. I simply hoped I would wake up and I would be better. I knew my reality was that my body either dealt with this or it didn’t.

I have always felt that if it’s your time to go then that’s the way it goes. It’s important to ask yourself the question: have you been living the life that makes that OK? I was doing what I loved to do. I was a realist. People die. That’s it. If I hadn’t believed that, I would never have done the things I did in my life. I drifted off into dreams. When I woke up the icy wind had died down and the morning light shone through the trees.

I had spent that winter living at my mom’s house near Langley, British Columbia. My brother Klint was paying rent to stay in the bottom suite. I was sleeping outside with the dogs. First of all, I had become used to living outside in the winter and in general I found houses to be too hot. Secondly, I was an extremely stubborn 18-year-old and I tried to do everything in the hardest way possible. Sleeping outside was one way for me to exert my independence. To make a point. (To somebody. About something.)

Perhaps I believed humans shouldn’t live like they were living: in a perfect environment with tons of food and no hardships, no tests. We as a species have spent however many hundreds of thousands of years living in sync with nature, then within a period of two hundred years we have advanced so quickly that we now dodge the laws that nature has set out for us. I think there’s a price to pay for that.

It’s amazing how much the body will always try to get back to softness and all-around weakness. There’s a mental aspect to that, but the physical aspect was what was so clear to me. If you are in an environment that enables you to eat junk, not move, and disrespect the laws of nature, your circadian rhythm, then you’re switching genes on and off and it’s killing you. You just become a soft blob. Was I running from that? Have I always been running from that? Am I afraid of that?

You’re fucking right I’m afraid of that. That scares the shit out of me. Always has. That is death to me. So sleeping outside was a mini accomplishment for me: a way for me to deal with the cold and the wet and stay true to what I believed. To Klint I was a crazy younger brother (To me, Klint was debilitated by having fallen in love). To Mom I was a disgruntled late teenager. But she was happy because, for the time being, at least I wasn’t up on a mountain.

I worked odd jobs in construction with some of my dad’s old partners, dysfunctional, alcoholic maniacs who were constantly on the run from the tax authorities (though they were hard workers, which is why my dad stuck around with them). I definitely wasn’t happy there, but I knew I had to jump through hoops to get money to do the things that did make me happy. They paid well, and a guy like me didn’t have too many opportunities to make good cash. Even so, I was counting down the days until spring came around. This job would be over and I could go on my next trip. And I was going to Alaska.

Langley to Alaska is a journey of over 2,500 km. After some previous trips cycling had become an addiction, but it wasn’t about speed or distance. It was an addiction to exploration and to the possibility of excitement beyond my little mountain range in southern BC. I wanted to go north to where it was really wild because, other than the odd forestry area, the landscape was exactly how it had been for hundreds of thousands of years.

I was insistent on doing everything old school. I shunned technical equipment apart from my $10 Gore-Tex jacket picked up at the Value Village thrift store. I planned to carry a tarp and a woollen blanket. I would wear woollen clothing. I wanted to cook everything by hand, so I was going to leave my camp stove behind and commit to building a fire every night. I had already learned a lot about fires from my time messing around in my mountain camps but I wanted to become so proficient at building one that I could even do it in the pissing rain.

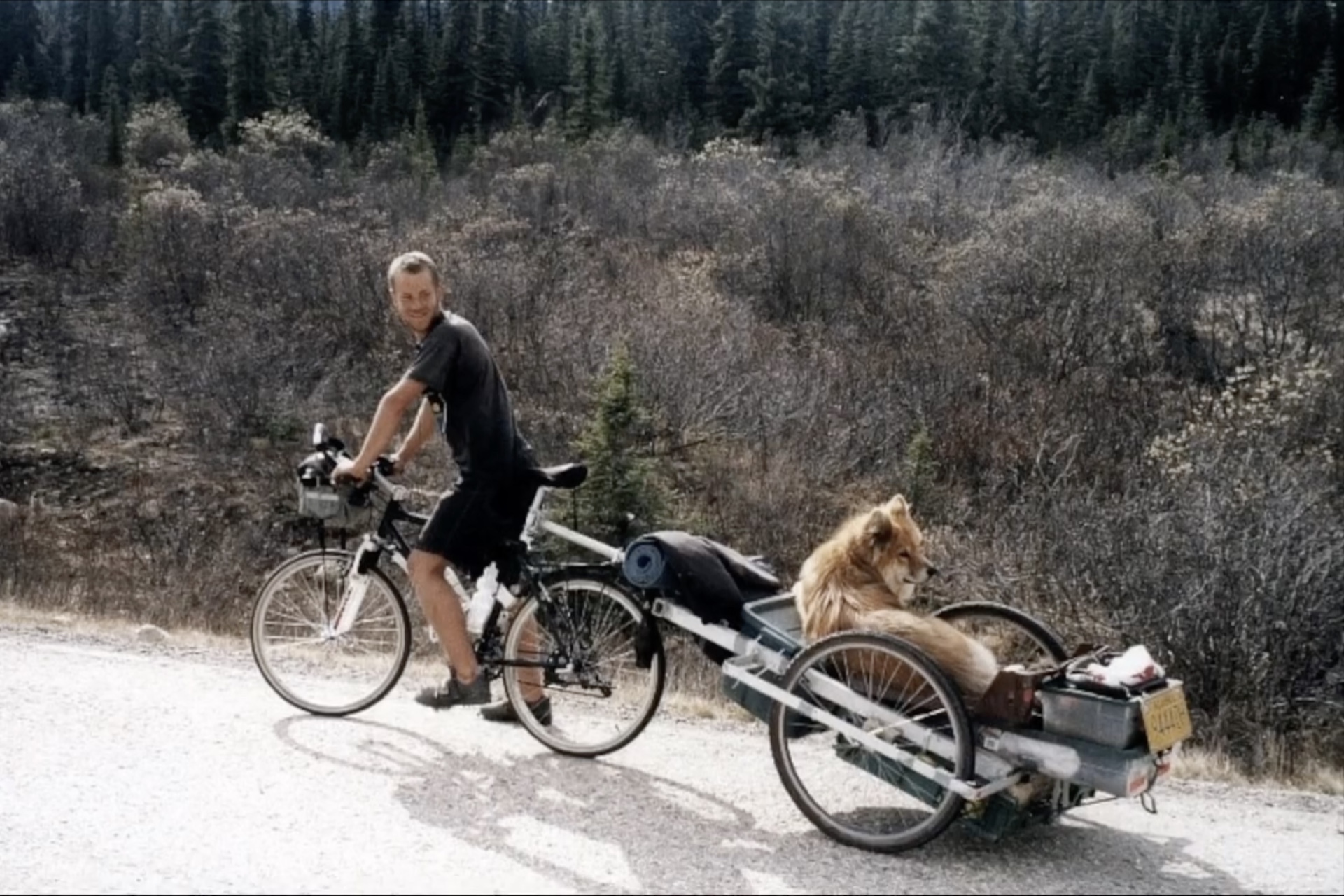

I saved $800 for a new aluminum Trek with Rock Shox front suspension. I went down to an aluminum salvage place and bought parts for a new trailer. I wasn’t skilled enough to work with aluminum without melting the whole lot into a hot puddle, so I cut my pieces by jig and paid a specialist a hundred bucks or so to weld it together. Inside the trailer were two large Rubbermaid containers: one for soft items and the other, more accessible, for food. I strapped a heavy-duty plastic bread crate to the frame for the dog to ride on. Once that rig was packed up, I had my ticket to freedom.

One hundred kilometres north of Langley, you are truly in the wild. No farms, no properties. It’s Crown land. It belongs to the public, the people, and it means that as long as you’re not being an asshole, nobody will come and harass you for being anywhere. That meant that there was never any stress when it came to finding somewhere to camp. Depending on my food situation and how I was feeling, I might stop early or I might continue riding long after the sun had gone down. I would keep my eyes peeled for a little forestry side road to get away from the highway and would search for a flat place out of the wind and, on this trip, one with some good firewood.

Once again I planned to survive off food like oats and canned beans. The latter was so easy: crack the can a bit, chuck it on the fire, hot beans and sugar sauce, quick and delicious. When I was feeling pretty fancy I would buy a loaf of bread, and if the shitty peanut butter was on a good deal I would buy a couple of big tubs of that. Maybe some honey. A long way from dining at the Ritz, but pure energy. Chocolate milk was still my crack cocaine: I would sit down at a gas station forecourt and mainline a litre of that. One thousand calories in one hit. Perfect for bike riding.

I left home at the end of April, the first stint taking me north along the same roads as my previous trip to Bella Coola. At Williams Lake I continued north to Prince George and from there I headed west on the Yellowhead Highway. Right away, I turned onto gravel. This was how it was going to be from now on. I would make good time on some sections but if I hit a section of soft stuff that had just been graded, I would find myself pushing half as hard again just to maintain my speed. Then a truck would come past spraying calcium carbonate: a spray they use in concrete mix that hardens the soft, graded gravel. Riding through fresh calcium carbonate is not dissimilar to riding through concrete mix. The stuff quickly hardens to form stalactites on the bottom of the bike and jams the brakes and gears. I had to keep stopping to scrape it all off the bike. That was a big eye-opener.

The other big eye-opener was this: up until this point I had been in northern BC and there were still gas stations every 100 km, at least. Your typical small resource towns had very little going on but, since they had real food for sale, I could make a go of it thanks to those gas stations. I could buy perhaps a bunch of bananas and a can of beans and be good for the night. On the Yellowhead Highway, in those days, there was nothing. I could easily go 200 km and see nothing.

Well, not quite nothing. Maybe two hours would pass and then an 18-wheel truck would come by at 100 km/h and spew gravel everywhere. The rest of the time the black bears would come out. Swathes of forest either side of the road had been cleared to stop trees falling on the carriageway, so there was quite a lot of fresh greenery for the bears to come and eat. On some days I would see 20 or 30 bears, with cubs. Black bears aren’t out to get you. They just want privacy and to be left alone. Grizzlies are different. I knew there were grizzlies further up north but they stayed in the high country. Thankfully.

Of course I had a bear of my own. Bear. This, however, was my second Bear because my dad had taken quite a liking to Bear One and more or less adopted him. Bear Two was a Chow-German Shepherd-Rottweiler mix from the same parents as Bear One, but he had a beautiful foxy red coat. He was a large part of why I seldom had problems with animals. Bear Two was nuts.

I could tell if there was a bear in the vicinity by Bear’s nose, which would start going full gas. Real bears don’t want to fuck with dogs, especially psycho dogs like Bear. It’s just not worth it. One of the annoying things about Bear was that he would chase anything that ran from him, which in those days meant most of the animals in the forest. Moose, deer, bears: when he left I just had to park up wherever he jumped off the trailer, set up a mini-camp, throw out the blanket, read a book, and hope it wasn’t raining. Sometimes I’d be waiting five minutes, sometimes two hours. Regardless, he would always come back fucked. Panting. Often cut up like he’d been in a fight. But always happy as a dog can be.

I looked like hell too. A few times coming into a gas station I would catch a glimpse of myself in the reflection of the door, or inside on some mirrors. Everything was filthy. I’d pull into creeks for a dip only to have everything plastered with dust half an hour later. Yet people would see my setup, see my rig with the dog, and immediately start chatting me up. Often I’d end up talking with someone for half an hour and before I knew it they had invited me down the road to their place for dinner and I would get to meet the family and have a hot shower.

There were older couples whose kids had left home and who wanted to take me in for a little bit, have me around for a while. Maybe they had a fence that needed painting or some odd jobs to do, and I would spend a day or two there and make a little cash. People were very generous and I think a lot of that is down to the dog. A dog is a real icebreaker for people who might otherwise think you are an absolute weirdo. They see a dog and they think you can’t be that bad. Mind you, I could leave that bike and trailer anywhere. Nobody was touching it if Bear was with it. He didn’t especially like other people.

If there’s one thing I wish I could recreate from that trip, it’s the surge of life I felt that morning on the side of the highway. After that night drifting between waking and sleep, I came back to life. I was lucky. Whatever infection had tried to take me out had been killed. I had beaten it. I began to hack these big, infectious loogers out of my lungs and it was one of the most glorious feelings I have ever experienced. The power and the resilience of youth. The happiness and excitement of riding. The magic of bike touring.

It grabs you. You’re rolling along and you see a sign: “Dease Lake 60 km.” It’s 2PM and you ask yourself if you can get there before dark. Then you start pushing. The road turns to shit and there are a load of climbs, so you push some more. You stick a cassette in your Sony Walkman and get stuck in. Before you know it, you enter a trance. When you’re rocking out and riding along, you’re not thinking about anything else. I fell in love with that feeling. And on top of that I was going into unexplored, fairy-tale lands. Tree stumps were the size of motorhomes. Every moment was a wonder, every kilometre down the road was a new place.

I had no stress in my life. I owned next to nothing. I had no cell phone (nobody did). I had no bills to pay. I wasn’t trying to figure out life; I was happy as a clam to be living for what was around the next corner. On top of that I was proud of myself and proud of what I was doing. I didn’t give a flying fuck what people thought of me. I knew I was doing something for myself and that it really felt special to me. I felt like I was accomplishing something.

It wasn’t all perfect. Before arriving in Dease Lake I broke my saddle, a big, springy thing I had assumed would be more comfortable (I had no bike knowledge at this point in my life). I duct-taped my shirt around the seatpost so that I could at least lean a cheek on it without getting speared and I stood up and pedalled 150 km to town. I’d thought it would be a big place but it was essentially a gas station grocery and a few other services. I ended up buying a saddle off a mountain bike that belonged to a guy who worked in the grocery store. It was a proper leather racing saddle. He sold it to me for 20 bucks. That was a serious financial hit but it was what I needed to do.

Life is like bike touring. It’s all about moving forward. I slapped that sucker on and continued north.

Did we do a good job with this story?