It started with all the ingredients that product marketers dream of. A world-famous university, advanced military research funding, and gold medals in a home Olympic Games. Following the 2012 London Olympics, an experimental product called DeltaG, a ketone ester drink developed by Oxford University and funded by a US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) project grant, went public. In what is by now a well-worn story, British athletes across a range of sports, including swimming, rowing and cycling, are said to have been testing the product behind closed doors in the lead up to the Games, many going on to personal bests, world records, and Olympic gold.

The story in many ways parallels creatine supplementation, which 20 years earlier rose to fame at the Barcelona Games following gold medals to British track stars Linford Christie (100 m) and Sally Gunnell (400 m hurdles), who claimed creatine helped get them there. Creatine has since gone on to become one of the world’s most researched and recommended supplements (behind only caffeine), not only for performance but increasingly for health benefits too.

But a decade on from London, are ketones following the same trajectory?

What are ketones and ketone supplements?

To understand ketone supplements like DeltaG, first we must understand ketones in the broader sense. Most of us, most of the time, rely on a mixture of fat (mostly as fatty acids) and carbohydrate (as glucose) to fuel our bodies, both at rest and during exercise. There are other fuels and factors at play, but we don’t need to fret the details here.

What’s important is that when there is adequate glucose to go around, it will be used for fuel, especially in organs like the heart and the brain. If glucose is lacking, however, either due to prolonged fasting, starvation, or a deliberate dietary restriction (i.e. low carb, high fat diet), fat becomes by far the predominate fuel source. At the same time, the liver begins using some of this fat to produce an alternative fuel to glucose, known as ketone bodies, or simply ketones. This is the process known as ketosis, the main goal of ketogenic diets.

There are three main types of ketone bodies produced: acetoacetic acid (acetoacetate), acetone, and beta-hydroxybutyric acid (βHB). Normally at rest and not in ketosis, we have a blood βHB concentration (this is what most commercial ketone meters actually measure) of less than 0.5 mmol/L. When ketosis is induced through carbohydrate restriction (known as nutritional ketosis), this level rises to around 1-3 mmol/L.

Ketone supplements provide an external source of ketones and can elevate blood levels to those similar to (or slightly greater than) nutritional ketosis, even if you’re not deprived of glucose. The idea is that supplemental ketones provide an additional fuel source rather than an alternative one.

The supplements themselves can be divided into three distinct categories, based on their chemical structure:

Ketone esters

The ketone body is bound to a precursor molecule (like butanediol) via a process of esterification. The bond between molecules is then broken during digestion to make the ketone available, and the precursor can be taken up by the liver to produce even more ketone bodies. There are multiple possible combinations of ketone body and precursor that can be produced, meaning that the results of any studies of one ketone ester may not always be directly comparable to another.

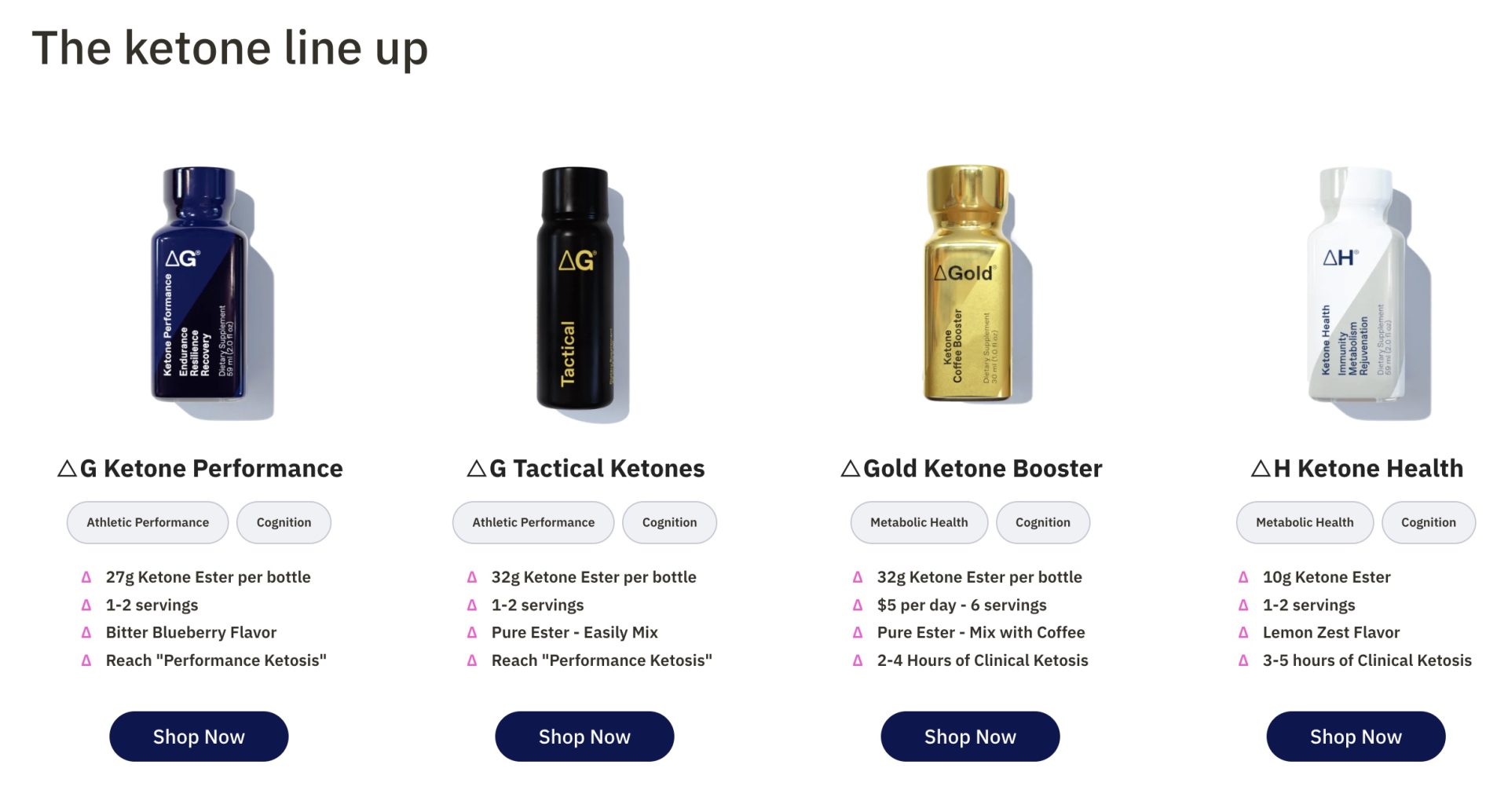

The patented DeltaG formulation that was developed and first tested at Oxford was then licensed and commercialised in 2017 by the American company HVMN. The company no longer sell it however (more on why shortly), and the commercial sales are back under the DeltaG name, sold through TdeltaS, a spin-off company from the research group at Oxford.

But there are two things that really limited commercial uptake of this product. Firstly, the cost: a single serving set you back US$30 in 2018, and today DeltaG sells for about the same price. Secondly, and just as importantly, is the reportedly awful taste of ketone esters.

Ketone salts

These are ketone bodies (usually βHB) bound to a mineral like sodium, calcium, or magnesium. Ketone salt products hit the market as a cheaper and better-tasting alternative to the patented ketone ester. However, research has found that ketone salts fail to elevate blood ketone levels to nearly the same extent as the esters, and have other potential side effects (see below).

Ketone diols

The newest kid on the block commercially (and now the sole ketone product sold by HVMN). Available since 2021, this product provides purely the butanediol precursor rather than ketone body bound to it. The butanediol can then be converted to a ketone body in the liver and appears to elevate blood ketones over a longer time than the esters, but not to the same level.

The main benefits of this approach are significantly reduced cost (now ~US$5 a serve instead of $30) and improved taste compared to ketone esters. Many users of butanediol also report a sensation from it which has been described as anything from a “caffeine-free buzz” that provides positive reinforcement, to a “woozy” feeling not dissimilar to alcohol, which may be seen as detrimental.

The use of ketones in pro cycling

Many Escape Collective members will recall stories emerging from the 2018 Tour de France, where teams were rumoured to be using ketone esters. Most heavily tied to these rumors was Jumbo-Visma, a team which confirmed their use but stressed that it was very much experimental – an attempt to gain an advantage if it later turned out that one was there.

This kind of FOMO/arms-race mentality is not uncommon (or undesirable within rules and ethics) for elite sport, as teams or athletes adopt practices that they’re not yet convinced will be beneficial, but don’t want to miss out on a potential advantage from (and lose out to their competitors) in case research later finds their concerns unfounded.

Even earlier than this, at a scientific conference in 2017, it was discussed that the GreenEdge squad had tried ketones at a team training camp. In their case they had used ketone salts since the ester product was not available to them at the time.

Their use didn’t last long though. Due to the high dose of minerals being taken in one hit with ketone salts, riders experienced severe gastrointestinal side effects, including nausea and vomiting, which ended the experiment almost as soon as it had begun, much to the bemusement of Professor Keiran Clarke from Oxford who was presenting her work on the DeltaG ester at the same conference.

Do ketones improve one-off performance?

Whilst the early studies at Oxford were being conducted around 2012 and the first research paper published in 2016, it has really only been in the last five years that the commercialisation of ketone esters has opened the door for other researchers to get involved. For this reason, research on ketone supplements for athletes is still considered very much in its infancy.

The original Oxford study, using the DeltaG ester and published in 2016, involved eight highly trained endurance athletes drinking calorie-matched drinks of either ketone ester with carbohydrate or carbohydrate alone, 20 minutes before exercise and at the end of a one-hour ride at 75% of their power output at VO2max. The cyclists then completed a 30-minute distance trial to measure performance. Think of this like an hour record attempt, but in a lab and, well, 30 minutes. They found on average a 2% performance benefit (411 m further) when consuming the ketone ester.

As a side note, if you’re wondering how a 2% benefit compares to other nutrition strategies, this is not particularly remarkable. Caffeine, perhaps the most extensively researched supplement of all time, typically finds average benefits of about the same extent. And whilst it’s a story for another day, a common theme in supplement research is that when you combine two supplements that have shown a 2% performance benefit in isolation, you rarely get a 4% response.

Back to the ketone study though, and of the eight participants (six male, two female), five saw performance benefits (one by almost 1.5 km which dragged up the average), two saw no real effect either way, and one a decline in performance of almost half a kilometre when taking the ketone ester.

Fast forward to the present, and over 20 studies on different types of ketones and performance have now been published. A review in late 2022 scanned the published literature, finding a range of studies using either ketone esters (11 studies), ketone salts (eight studies), or the butanediol precursor (two studies).

At the time, no beneficial effect had been demonstrated in any studies of the butanediol precursor. For ketone salts, of the eight studies conducted only two found positive results, and one a detrimental effect. Of the studies with positive findings, one did so in a formulation that also contained caffeine, and the other was an 800 m running time trial, where participants took the supplement daily for 10 days prior.

For ketone esters, the 11 studies have produced only two positive findings, both with the DeltaG formulation. One was the original Oxford study discussed above, and the other a study of a simulated rugby union match with various performance tests interspersed throughout the simulation. The remaining studies, using different combinations of exercise types, intensities, durations, and nutritional conditions (e.g. fasted or with carbohydrate feeding), and using either DeltaG or other ketone mono- and di-esters, have failed to show beneficial effects on performance. In two of them participants actually performed worse on the ketones.

The findings of these individual studies are now reinforced by three separate meta-analyses, studies that use a statistical method to combine all previously published studies to produce a single overarching result, which all concluded that ketone supplements fail to improve one-off performance.

There are a couple of caveats to all this research. Firstly, almost all these studies have looked at performance in high-intensity efforts (how well you can perform over distances or durations of up to 30 minutes, even if there was a lower-intensity component beforehand). This type of study design may be useful for professional road cycling where races are typically won and lost in shorter, higher-intensity efforts near the end of a race, but possibly not for those trying to optimize performance in a gran fondo, gravel race, or endurance MTB event. Also, given how quickly the ketones in the ester enter and then leave your bloodstream, the suggested use of these products is a dose about every 30 minutes of exercise. Even with the new, cheaper 1,3-butanediol, that’s still around US$5 for every half hour of exercise (be thankful it’s not $60 an hour like the ester!)

Second, and one factor that’s led to some very recent research, is that in almost all of the studies ketones are given in conjunction with carbohydrate, rather than as an alternative. A very recent study has found that ketones alone (compared to carbohydrate alone) might improve running economy (the amount of oxygen required for any given effort). This has the potential to lead the ketone and performance research in a new direction, but not one we’ve been down yet.

Could ketones help in other ways?

Rather than just studying the effect of ketone supplements on one-off performance, researchers have also been looking at whether ketones could improve post-exercise recovery, or the long-term adaptations to training (the body’s response to training that makes us better athletes over time). This also fits with anecdotal reports from athletes that the ketone supplements weren’t necessarily helping them perform as a one-off, but did help cope with high training loads, or improve sleep during more demanding training blocks.

Again, it was the group at Oxford who published the early studies of ketone supplements and recovery. In 2017 they produced a paper that concluded that ketone esters (DeltaG) could improve the extent to which carbohydrate stores in the muscle were replaced after being depleted during exercise, albeit only to a small extent.

The study has attracted criticism however, because it both created a somewhat artificial state of elevated blood glucose beyond what is normally seen during post-exercise recovery, and because participants were not provided the same number of calories post-exercise in the placebo trial, which has been shown previously to effect carbohydrate restoration. A follow up study could not reproduce these findings, albeit the study protocol was quite different. They did find, however, potential benefits for the way muscles repair and incorporate new proteins following exercise. Which brings us to adaptation.

Better training adaptations would theoretically mean that you are getting more benefit from the same training program. Scientists start getting excited when they can find direct or indirect evidence of such adaptations, but they also know that it doesn’t mean anything unless it translates into measurable and meaningful changes in a desired characteristic (e.g. body composition, performance, etc.) over time.

One highly sought-after adaptation is increased muscle protein synthesis, which if achieved frequently enough should add up to muscles that are better at whatever type of training they’ve been subjected to. In this case, the DeltaG ketone ester was found to increase some of the signaling molecules associated with muscle protein synthesis.

The key phrase is “associated with”. At this stage there are no direct measurements of protein synthesis, much less longer-term studies to show that ketones do indeed increase the muscle’s adaptation to training. So while this finding is a promising result, it will take time to see whether it does in fact translate into truly beneficial effects.

There have also been two studies that found increased levels of (naturally produced) EPO in the blood when using a ketone ester after exercise. But again, the research is in its infancy. It’s not yet clear whether this increase in EPO is fleeting or persistent, and if it’s sufficient to actually make a difference to hemoglobin mass (and ultimately performance).

We also don’t know how long you would need to supplement with ketones for to achieve any meaningful benefit. The protocol from ketone companies suggest customers need 2-3 doses of the product daily outside of exercise to maximize the adaptive response, so even with the cheaper 1,3-butanediol product you’re talking about $100 a week. This might sound excessive at first, but compared to flying to a location at altitude, it may actually represent decent value for money for elite and professional athletes, if (and only if) the initial findings are shown to lead to the sought-after benefits.

Finally, other potential benefits of ketones have been suggested, like reduced skill errors, better alertness, or tactical decision making. And whilst there has been a study here or there to demonstrate these benefits (e.g. in soccer players), there have been just as many that failed to find such benefits.

Other claims suggest that ketone supplementation “spares glycogen”, the stored form of carbohydrate, and when combined with improved movement economy perhaps performance benefits will become evident in ultra-distance gravel and MTB races, or events like Race Across America.

Studying objective performance that’s representative of what happens in these events is near on impossible however. This makes ultra-distance racing a) an area where we’re left to try to extrapolate theory into hypothetical outcomes, and b) a notorious place of eternal hope for strategies that failed to prove their worth in shorter, higher-intensity events (“But what if it did work? If only we could study a 15-hour time trial in the lab …”).

The bottom line

Because ketone esters have only been available commercially for about six years (and the diols even less), scientists are only really starting to piece together the puzzle of their use with athletes. After much hype and a dream origin story, what we are now seeing coming out of other university labs is thin slithers of theoretical benefits mixed with equal doses of doubt, but very few tangible outcomes that would see ketones rivalling the established players like caffeine or creatine as supplements of choice. At least that’s how things are now.

It’s true that when it comes to elite sports, research tends to trail behind the real world by a couple of years (or more), and perhaps athletes have found benefits from ketones that haven’t been scientifically investigated yet. But a decade on from their first reported use, we’re still fishing around for a viable use case for ketones, which is a very different place to where creatine landed after 10 years in the hands of athletes.

About the author

Dr Alan McCubbin is an accredited sports dietitian, researcher, podcaster and practitioner in the field of endurance sports nutrition. He works with endurance athletes of all levels, from complete beginners to professional and Olympic athletes, and has previously worked with UCI Continental teams, and athletes from Triathlon Australia’s High-Performance Program in the lead up to the Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics.

Alan consults through his own business, Next Level Nutrition, training-based nutrition coaching app Fuelin, and is the founder and co-host of The Long Munch podcast. Alan started contributing to “The Other Place” back in 2011, and is a proud founding member of Escape Collective.

What did you think of this story?