“Sorry about the music,” says Cyrus Monk as he steps off the Q36.5 team bus in the backstreets of central Antwerp. Inside the bus, frantic Euro beats are blasting – a stark contrast to the relative quiet in this part of town. It's around 9am on Easter Sunday.

Finding the Q36.5 team bus wasn’t easy. Where the biggest teams have prime real estate, their buses parked alongside the Scheldt river, right near the Tour of Flanders start line, Monk's smaller, second-division team is in a secondary parking area with a few other smaller teams, a few blocks away, on the fringes of Antwerp’s red light district.

This is a big day for Monk. It’s his first Tour of Flanders and indeed his first Monument.

“It’s pretty incredible to be here,” the 27-year-old Aussie tells me, smiling broadly. “If you had have told me a few years ago that I'd be here racing Tour of Flanders … Having lived in Belgium for so many years, been here racing, scrapping away in some far less glamorous races, to now be here is pretty incredible.”

Monk describes himself as a “regular guy” who just happened to find himself racing some of the biggest races on the planet. That’s not entirely true, of course – the Victorian is in his second year with the ProTeam-level Q36.5, after many years spent slogging away at the Continental level. But being a Flanders newbie does mean he’s had to lean on the experience of others to prepare for Belgium’s biggest race. The main difference between this race and others? De Ronde’s 270 km length.

“I think the intensity has been so high in all the races we've done and from what others have said the intensity is actually a little lower here but the length is so much longer that everyone's completely dead at the end anyway, so they can't quite go as hard,” Monk says. “But the way things have been recently in the cycling world I'm not banking on the intensity being that much lower. I think everyone can just ride full gas everywhere now.”

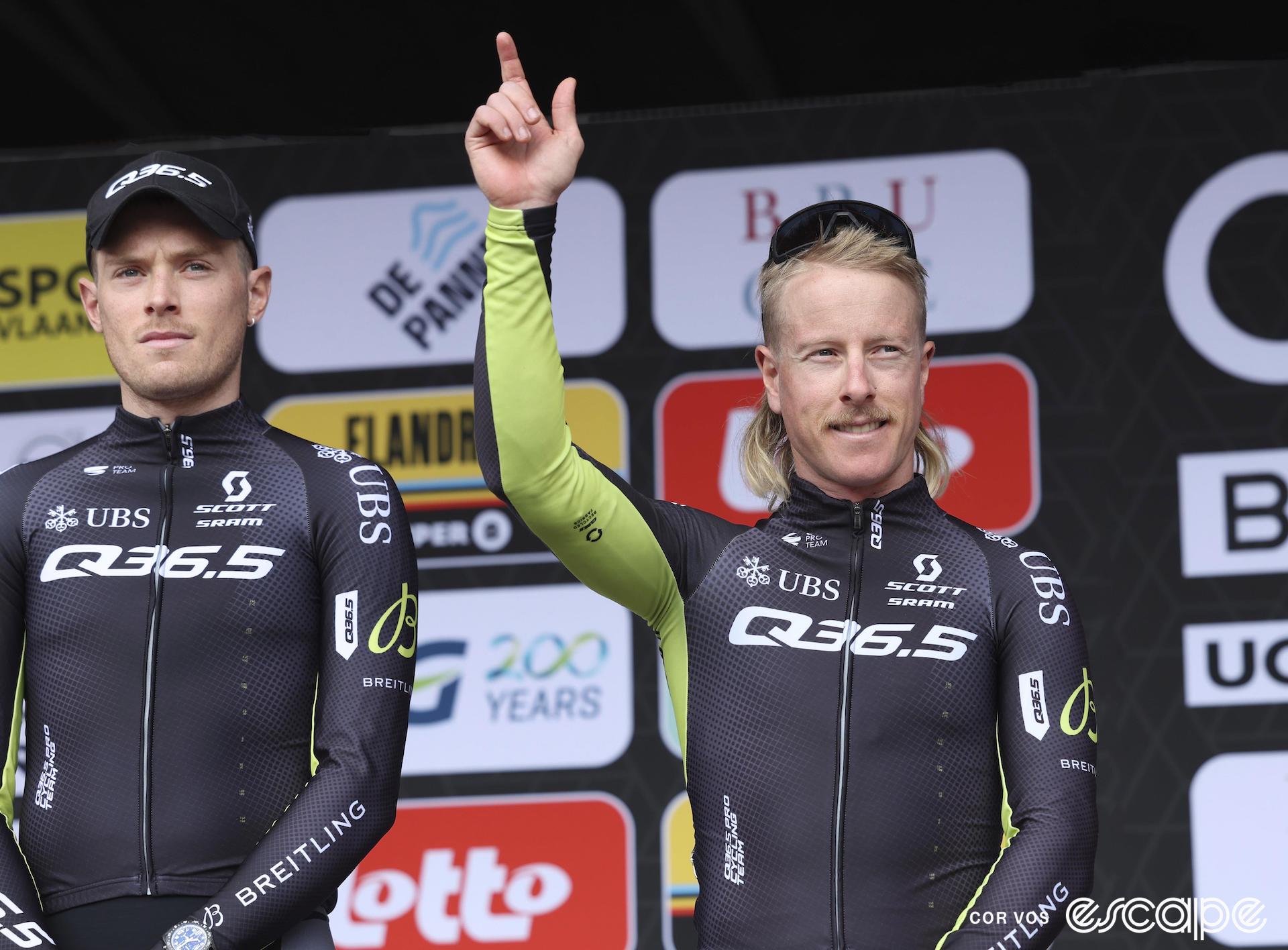

Monk isn’t one of the highest-profile riders in the Tour of Flanders; far from it. But to those familiar with his journey, he’s known as a breakaway specialist, a tireless worker for his teammates, a musician, a science communicator ... and the proud owner of one of the peloton’s finest mullets. This spring he’s found himself racing a full Classics program, most visibly with a ride in the breakaway at Gent-Wevelgem. Getting up the road is something he’s hoping for again at the Tour of Flanders.

“[Our] Classics team has just been decimated by injuries so we've lost our leaders so the goals have had to change a little bit,” Monk says, his arms crossed to keep himself warm in the morning chill. “Just get that exposure in the front … and also it gets you further into the race if you're just getting that head start on the best guys before they light it up on the climbs. So I'll definitely be trying but I think about 100 guys will be doing the same thing.”

Talking to Monk it’s hard not to notice the sizeable scabs he’s sporting. A big one on his shin, a bunch on his hands.

“I crashed at the start of E3 with about half the peloton,” he says. “It wasn't on TV so no one saw that one but yeah it has taken a lot of riders out of the Classics as well. But it's just part of the sport now. It's not something I like but it's just something that happens.”

Recovering from that crash has made for a rather suboptimal lead-in to De Ronde. And it’s not just road rash he’s had to overcome.

“[With] the long day in Gent I've just worn out one of the tendons in my leg so it hasn't been ideal and not good timing for it,” he says. “I’ve been doing a lot of work with the docs and physios and it's felt alright the last few days. I'm just hoping it holds up for six hours today.”

And while breakaway is a big goal, just making it through the entirety of the race’s six hours will be challenge enough.

“Really just to finish for me would be amazing,” he says. “For me to finish will mean that I have to be active in the race, I think, because if you're just trying to follow wheels, you get too far behind the race when there's splits and crashes and that kind of stuff. So both goals sort of tie in together and yeah, to finish the first Monument and such a hard Monument would be pretty crazy.”

Monk is one of the first riders up to the startline a short time later, reserving his place at the front to maximise his chances of getting in the break. After a small group gets up the road not long after the start, TV coverage shows Monk on the front on the peloton, trying to get away, trying to bridge across.

“Plenty of teams there were trying to do the same, so we were in effect just shutting each other down,” Monk tells me a few days later. “And then other teams were happy with the break and trying to shut us down. So there was a lot of energy spent for not much there, which is a bit frustrating.

“Last year, it took 100 km for the break to go so the direction from the sports directors was stay pretty calm for the first 20 km,” he adds. “‘Don't use all your energy then because that's when all the idiots will be jumping straight away’ and basically something stronger will go after that. And then of course 2 km into the race a group of eight were gone.”

Monk spends a good chunk of time dangling off the front of the bunch, trying to coax others to come with him, to bridge across. But to no avail.

“The peloton just slowly made its way back and by then I was completely spent and the gap had just been hovering between 20 and 30 seconds for so long,” he recalls. “I knew that if I was to keep going like that, then I wasn't going to make it to the 50 km mark, let alone the end of the race. So then it was just time to switch the goals to the next objective.”

That next objective is helping his teammates get good position into the race’s crucial cobbled climbs. After retreating into the peloton for a time to recoup some energy, Monk spends around 20 km on the front of the bunch on approach to the Oude Kwaremont. As the climb approaches and the pace increases, Monk finds himself drifting back through the bunch a little.

“There was a small crash just in front of me which I stopped behind and then enough people behind me decided they wanted to take a risk and try and ride through it,” he recalls. “They ended up just riding straight into the back of me and breaking my bike.”

With Q36.5 being one of the lowest-ranked teams in the peloton, Monk’s team car is way back in the peloton. The wait for a spare bike is lengthy.

“I had to wait for all of the peloton to come past then all of the convoy and there's nowhere to pass on that small road right at the bottom,” he says two days later. “It was about two minutes waiting for the bike and then got the spare bike. Mine's obviously in the middle of the car, because I wasn't one of the protected riders, so it was the hardest one to get to. And then got going again. By that stage I was last rider on the road.”

Monk rides up the Oude Kwaremont alone and starts to make his way back to the bunch. But every few kilometres he’s caught behind a crash, or a bunch of team cars attending to those who have fallen. He spends 40 or 50 km trying to rejoin the bunch, angry that his day has gone the way it has, through no fault of his own. By the time he reaches each cobblestone climb, fans are all over the road, hampering his progress. And worse, the gears on his spare bike have started to fail. What started as a nice day in Antwerp with blue skies, has turned into a thoroughly rain-drenched edition of De Ronde.

“I think just because it was so wet and filthy, I actually got stuck in the big ring,” he recalls. “So I did manage to ride like Paterberg and the Koppenberg in the big ring. But by that stage, it was pretty freezing cold and wet and each time I got to an intersection, police were trying to pull me off just for my own safety.”

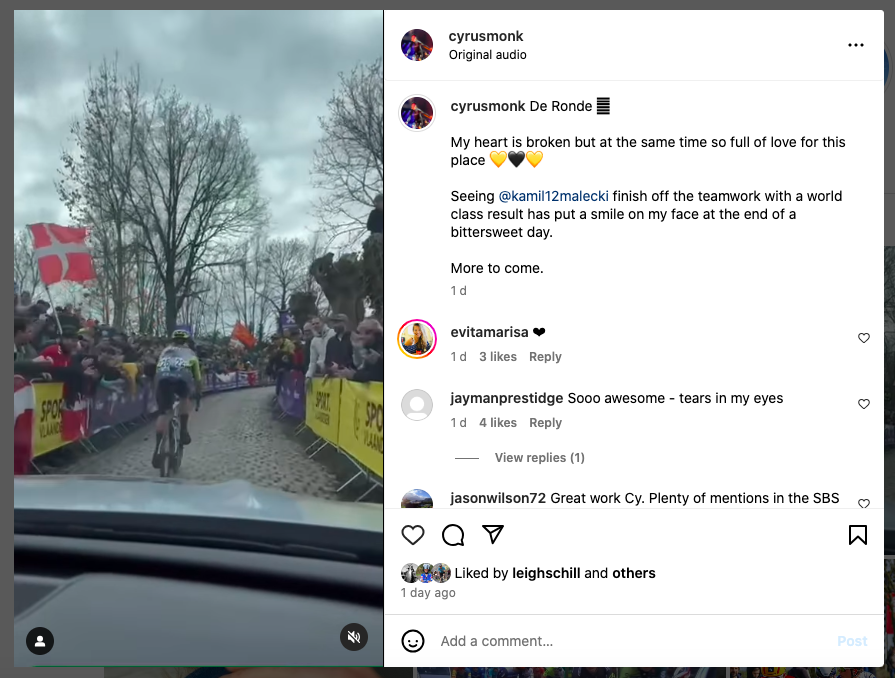

Soon enough, Monk’s race is over and he’s back in the team bus, now parked near the finish in Oudenaarde. In the immediate aftermath, he’s upset at not being able to give it everything. In the days that follow though, he starts to see things a little differently.

“I was really happy I was able to contribute quite a lot to to the team,” he says now. “And more so to have the contributions recognised. It's the kind of job that I do so often for the team, positioning them into key sectors and also just fighting for the break, making sure that we're present in these big races. But it doesn't get shown often because they don't show the first half of these races. And then suddenly everyone's actually watching the first half of this.

“I was getting all these really, really nice comments and messages, because people are actually noticing the work that I've put in. So it is good to get that recognition.”

As Monk watches on in the bus, his teammate Kamil Małecki takes 14th place: “one of the team's best results in the Classics,” Monk says, “considering how decimated we've been by injuries and illnesses.” The Australian’s efforts earlier in the race have contributed to a satisfying result for the team.

***

When we speak a few days after Flanders has finished, Monk has just finished a ride and is looking ahead to his next race: Wednesday’s Scheldeprijs, a semi-classic traditionally contested by the sprinters. More bad weather is forecast and again Monk finds himself with a sub-optimal lead-in. “I've been changing wound dressings because I managed to knock off all the wounds in that crash [at Flanders],” he says.

He’s not trying to look too far beyond Wednesday’s race, but all going well, there could be another Monument in his near future.

“It looks like it's gonna be crosswind, a bit of chaos, so won't be an easy sprint day, necessarily, like it has been in the past,” he says of Scheldeprijs. “So that'll be a tough one. And then at the moment I'm also on the list for Paris-Roubaix, which will be super-exciting, but I don't like to get too far ahead because anything can happen in these races.

“At the moment the main focus is for tomorrow and then as long as I get through that unscathed, then I'll be going to hell on Sunday.”

Did we do a good job with this story?