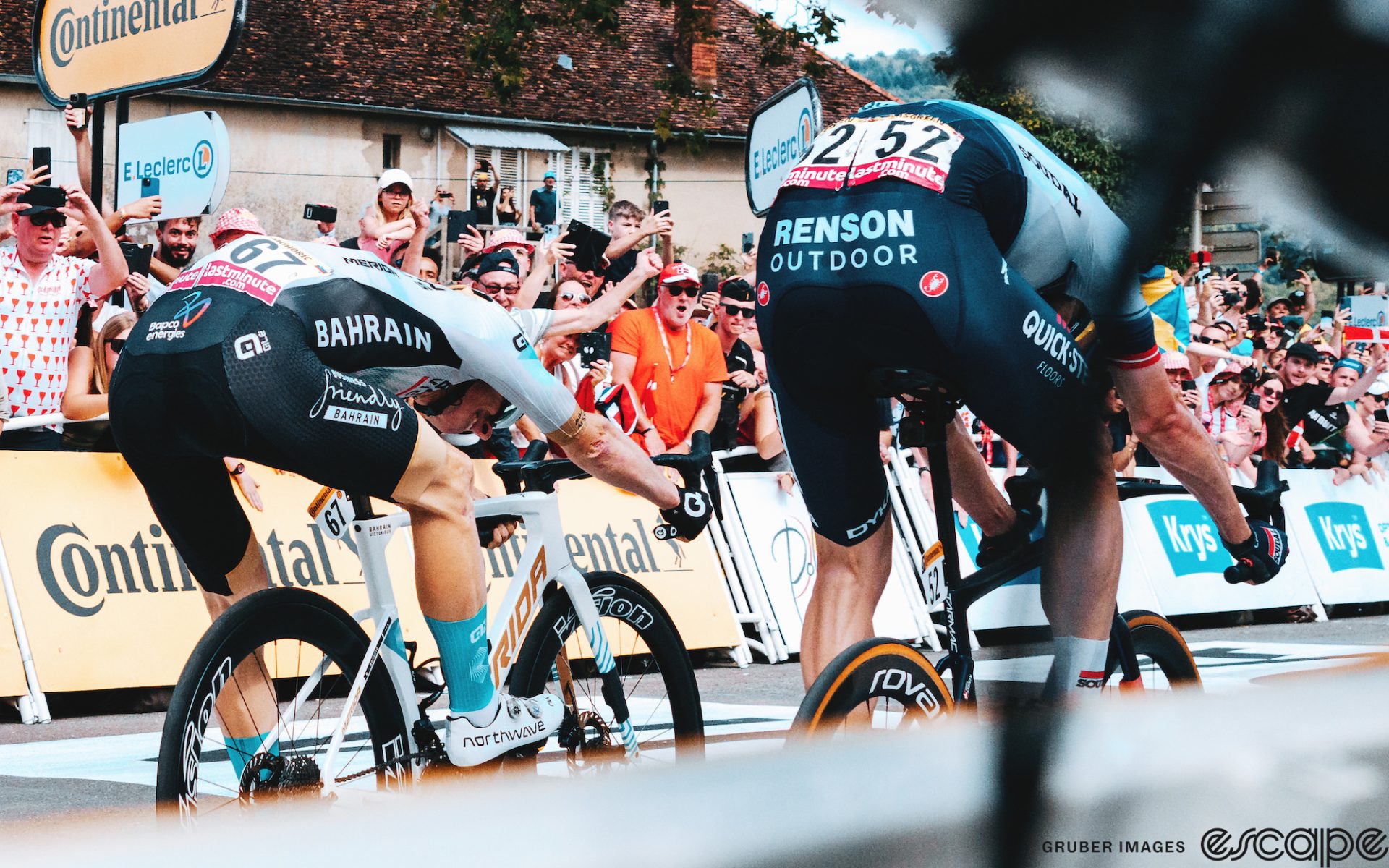

When he found out he won, that he had beaten Kasper Asgreen in a sprint determined by millimeters, Matej Mohorič burst into tears. He collapsed onto the ground and wept, consoled by teammate Fred Wright, his fellow erstwhile breakaway companion, who embraced him. Two years ago, the Slovenian ace had won on this same stage – the 19th – in the same way, from the breakaway. But he hasn’t had it so easy since then.

Mohorič began 2022 with impossibly high expectations. But after his win in Milan-San Remo, he just kind of faded away. He suffered from Epstein-Barr virus during that year’s Tour, which crippled his efforts. He changed, too. A man known for his verboseness and intelligence became distant and withdrawn. Four-minute answers turned into a minute and 40 seconds at best – still long by pro cyclist standards, but clipped for Mohorič. People all of a sudden began remarking that Mohorič had been in the peloton for 10 years already. Time flies, doesn’t it?

After taking the final stage in the 2023 Tour of Slovenia – another emotional moment for him, having come only two days after the passing of Gino Mäder, to whom he was a mentor – Mohorič tried for a win or to make his way into a final breakaway many times this Tour. He especially tried in the mountains, in Puy de Dôme, on which he – a 72 kg breakaway specialist matched against a pure climber and a minute behind the leader to start the climb – finished a remarkable third. He said in the press conference today he wanted to win that day for Mäder, simply because “Gino was a climber.” Yet everyone going into the Tour saw stage 19 and thought, that’s a Mohorič stage. Lumpy, prone to a breakaway, which in the end took a hell of a lot of time and effort to form.

Mohorič is best understood as a kind of engineer, not only in his perfectionism and technical prowess but in his ability to judge situations in an analytical way. He is also a social engineer – capable of adapting to scenarios in which he has to encourage others in a breakaway that the end goal of working together is more important than whatever threat he poses.

He has said more than a few times that he tries to picture the race as if he were a sports director, as though he could see himself from the perspective of the helicopter. It helps him make decisions. His outpouring of emotions comes from a place of necessary and ruthless repression, required of him when judging the mishaps of others and being able to capitalize on them.

The tears after the stage speak to an uncomfortable fact, which is that all struggles in cycling extend beyond cycling, because cyclists are human beings and all human beings struggle. Mohorič is a prime example of this. His post-race interview shed light on feelings we can all recognize in ourselves: acknowledgement of the cruelty of the world, gratefulness for the support of others, feelings of insecurity, and finally, relief that a long period of waiting for something good to happen is over. I think it’s actually worth quoting the first answer in full because it is such a complete picture of the reality of bike racing:

“[The win] means a lot because it’s just hard and cruel to be a professional cyclist. You suffer a lot in preparations. You sacrifice your life, your family, and you do everything you can to get here ready. And then after a couple of days you realize that everyone is just so incredibly strong, that it is just hard to follow the wheel sometimes, you know? And the other day on Col de la Loze, I was completely tired and empty and done with it. And you know, you have to go all the way to the top and across to the finish line and then do it again the next day, you know? And you see the staff who wake up at 6:00 AM [to] go for an hour to run, and then they finish their work at 11 in the evening or midnight, close the mechanics’ truck because we need to change tires, gears, everything, all every day, all day. In physio and massage and everything.

“And then sometimes you feel like you don’t belong here, because everyone is so incredibly strong that you struggle to hold [the] wheel sometimes. Even today, I was thinking the whole day, like, ‘The guy who’s pulling is suffering just as much as you do,’ but it’s just cruel to then be able to follow the decisive attack. When Kasper went, I don’t know, like he was so incredibly strong. He went on the attack yesterday and won the stage. And today to have the will and determination to do it all over again, like you just feel, you just feel that you don’t belong here.”

I think we often see these racers and assume that they don’t feel things like this, this insecurity, even guilt. Mohorič’s interview is a window on all of that, and his follow-ups in his press conference elaborated on some of it. He said he wished everyone could win a stage in the Tour de France, which changed his life. This sport requires an army of workers whose labor is invisible but means everything to the people who win, but almost never get credited in the way Mohorič credits them. It’s not just “the team” – it’s the mechanics, the soigneurs, the nutritionists with names and faces.

Some of these things, especially about the long days away from home and the toiling of the staff, he’s said before – including when he won Stage 7 of the 2021 Tour. The new addition is his reflection on his role as a breakaway artist, which by nature is inherently manipulative and parasitic – and as a result, this feeling of betrayal. I have never heard a rider say anything like this before, to express this genuine guilt of winning fairly. It signals a further turn towards the reflective in Mohorič, perhaps because of that 10-year career mark, perhaps because he just had a second child, perhaps because of Gino’s death.

The outpouring of support from fans for these statements is not only a testament to how rare they are, but how much fans love their athletes and want to hear what they really feel, see who they really are after removing that constant veneer of neutrality or diplomacy. This, of course, walks a difficult fine line between longing and harmful voyeurism. But again, I think this longing, as is the case for the longing to see real suffering, reflects a desire for the genuine in our own daily lives which are made of that same diplomacy.

Rest assured, Mohorič belongs where he is. He belongs on the long list of winners in the Tour de France. He belongs on the podium. I hope the overwhelming positivity towards him in his moment of great and human catharsis changes expectations around what we call sportsmanship but is often repression. I hope more riders thank their mechanics and soigneurs and express love for their teammates. Either way, Mohorič’s words can be read as both a kind of liturgy on suffering – mental, physical, emotional – but also as a fundamental text of cycling, one that will remain in memory for years to come.

And Matej, if you’re reading this, you didn’t do anything wrong.

What did you think of this story?