On Saturday the Tour de France Femmes takes on the most famous climb the young race has yet to tackle: the Col du Tourmalet. But it’s far from the first time the women have raced up the famed climb.

A lot of the details are lost to the mists of time, with limited results and stage details available. The specifics of past races that laid claim to being a “women’s Tour de France” are also complicated. In 1992 and 1993 there were two Tour-like stage races for women in France, one put on by the organizers of the men’s event and one that was in July.

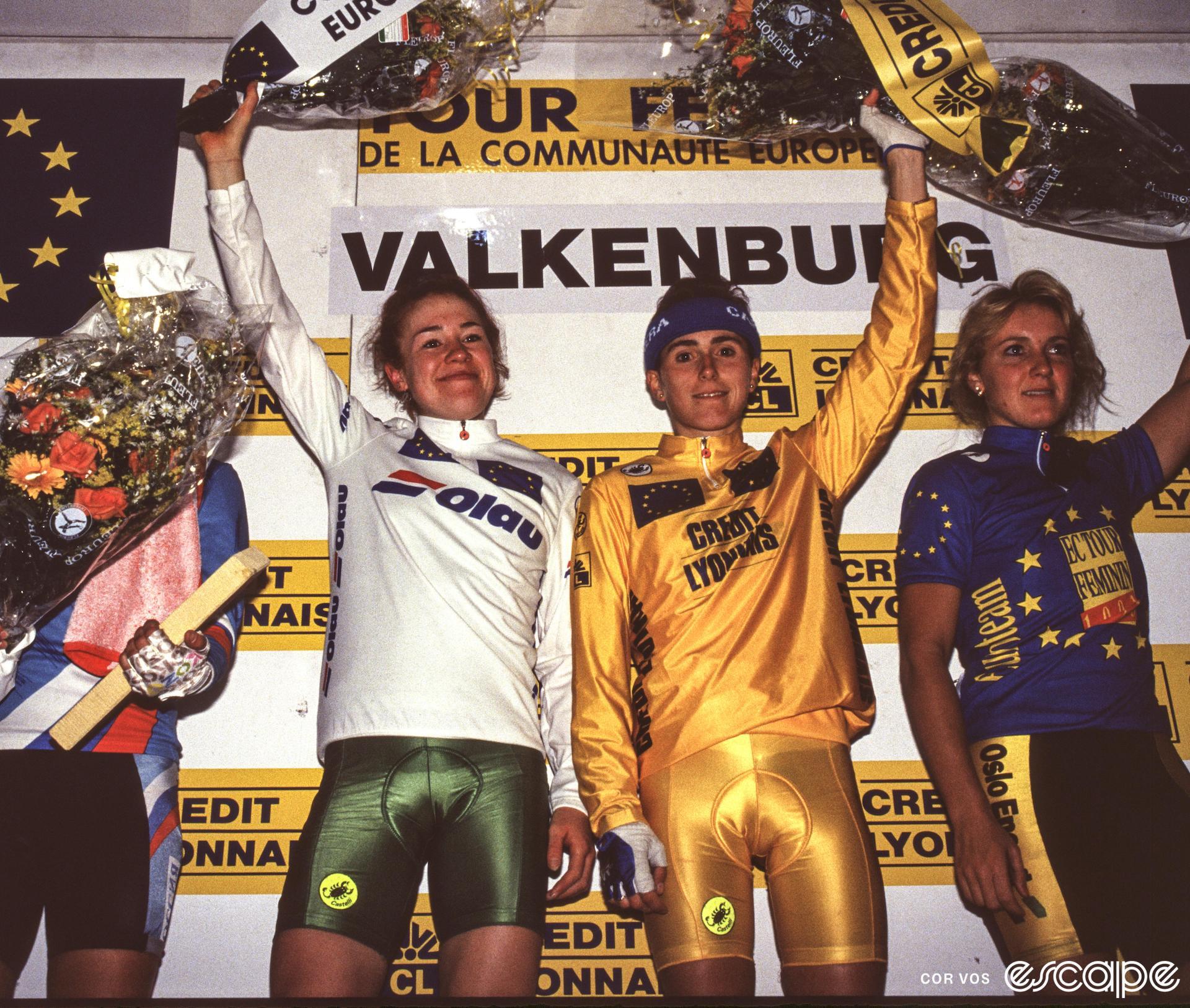

The second of the two, Tour Cycliste Feminin, later renamed Grand Boucle, was the one many consider the early stages of a women’s Tour de France. Like many racers of her era, Heidi Van De Vijver did them both, in both years, and the Tourmalet was a feature of both races – the Tour Cycliste Feminin in 1992, and the Tour de la CEE Feminin the following year. Until Lotte Kopecky’s stage 1 win this year, Van De Vijver was also the last Belgian to wear the yellow jersey in a women’s Tour.

In some ways cycling now is almost a different sport than it was in 1992 when Van De Vijver – now a director at Fenix-Deceuninck – raced up the Tourmalet. In other ways, it’s the same. “My legs hurt the same as [Annemiek] van Vleuten and [Demi] Vollering’s [will],” Van De Vijver told Escape Collective on the eve of the seventh stage of the Tour de France Femmes avec Zwift.

“The difference is that the bikes now are three kg less.”

“Also for the men, if you look back 10 or 15 years in the peloton there are also a lot of things that have changed,” Van De Vijver explained. Now, almost every WorldTour team, men’s and women’s, organizes an altitude camp for their riders before a big race like the Tour; nutritionists are on staff, and coaches are a must. Back in the 1990s even men had to pay their way to altitude, but for women it wasn’t even an option due to the cost.

“The material, the bikes, the training camps, I paid for my own training camps, in Mallorca but I never went to altitude camp because it’s expensive,” she said. “Now the teams arrange it. Medical support, they are smarter also now in what you have for food and nutrition.”

The last three years have seen massive growth for women’s cycling, with minimum salaries, more races at the highest level, and minimum mandatory live coverage standards from the governing body of the sport.

“In that Tour, I remember that we also did the Tourmalet,” Van De Vijver said of the 1993 Tour de la CEE Feminin. “Now this is only one real col or real climb. And it’s different, as in our Tours because we did in one stage like two or three [large cols].”

“It’s a long climb. And of course, I always was looking out to that because when you’re strong and you can climb, you get to the top and then you know three or four or five girls and it’s an honest stage.”

In those days the race that many consider the early version of the women’s Tour was routinely 12 or more stages long (including a prologue), half again, or more, what the women raced this year, and over 1,000 km. Both the 1992 and 1993 editions included a stage that peaked atop another famous French climb, Alpe d’Huez.

“I did a lot for myself, you can read books and think logically, but there was no internet, there was not so much massages, so it was the same in the men’s sport,” Van De Vijver said.

“These things they change so much, then there were only 20 riders who were paid to do what they did, but all the rest they worked part-time.”

Van De Vijver has seen all of the changes, not from the road – her cycling career ended in 2004 – but from the driver’s seat of a team car. She started in 2007 with AA Drink Cycling Team, directing for Kirsten Wild and Roxane Knetemann, and more recently for Fenix-Deceuninck.

Her team will walk away from the 2023 Tour de France Femmes as one of the most active teams in the peloton, with a stage win and at least a few days in the Queen of the Mountains jersey, but Van De Vijver wasn’t able to drive behind them during the string of success.

The former racer spent the 2023 Tour at home, watching the race on television. Now she is fighting a battle that is considerably more draining than racing up the Col du Tourmalet.

In May of 2022, she was diagnosed with esophageal cancer.

“I never, never, never expected this,” Van De Vijver said of the diagnosis. “It was like, it came from out of the air.”

“It was really crazy, and stressful and fear and everything during the [2022] Tour de France. Also, I could wait until September to get the operation and now, my body changed. My stomach, I don’t have a real stomach anymore.”

“You have another body. Mentally it’s also a struggle. I can’t eat or drink what or when I want. Now, OK, they say I’m cancer-free but it has to stay for four or five years to say, ‘OK, it’s gone.'”

Watching from home, and even in this different body, she still has the mind of a bike racer. She still watches the race and analyzes what could be done differently. According to her, racing aggressively is how to win, as we’ve seen her team do all week. Even if it doesn’t work out for the stage, like when Julie Van de Velde was caught on the line on stage 3, you keep going.

“OK, if you stay in the peloton you don’t win, because some stages, Lorena Wiebes or other top sprinters, 99% we can’t win, so why they don’t go or try?” Van De Vijver says of the attacking mentality missing from some other teams. “Sometimes I think ‘OK, they don’t have a goal, they don’t have ambition.'”

“Our team always tries to make the race and sometimes we lose and not so much times you can win, but now it’s that they feel it also. It can work; not much, but still.”

The strategy paid off when Yara Kastelijn won the fourth stage of Tour de France Femmes in spectacular fashion, holding off the chase to take the stage in Rodez.

“It’s really nice to see,” she said of the team’s success. “Because I don’t understand, also last year, it’s like I’m 17 years a sports director and I raced 18 years, and sometimes I don’t understand why there are not more teams who try to attack and race.”

From the second stage Fenix-Deceuninck has also been active in the fight for the QOM Classification, and Van De Vijver explained that any jersey is a victory at the Tour.

“For the mountains jersey, there’s not so much interest,” she said. “So that’s why I say it’s not sometimes not to understand how the teams race. You’re not racing to be seventh. You always try first to win.”

“So ya, you can lose if you try to win, 90% [of the time] you lose, but there’s also a chance you win and if you don’t try then you never have a chance. For us it’s great.”

This Tour has been an interesting one. During the stage won by Kastelijn, the breakaway racked up over 10 minutes advantage at one point – not something you see every day in a women’s event.

“No breakaway ever has 10 minutes in a women’s peloton,” Van De Vijver pointed out. “It’s maximum five minutes because the teams are only six or seven, and on a stage like that stage, up and down, you can’t organize a proper chase with five or six,” she explained. “That’s why also in the women’s peloton it’s rare you have 10 minutes.”

Looking to the Col du Tourmalet, Van De Vijver thinks it will be one or two riders who arrive at the top together, although she hopes there are more.

And while the racing might look very different from her days on the bike, the mountain itself remains the same.

“The fans in that period, there were also for us a lot of fans,” Van De Vijver recalled. “I think it was because the French team was really strong. Also with Jeannie Longo. She was for three years my teammate in the French team so I think that had an effect for sure.”

“Of course, when I was last year in the Tour de France, the new one, the Tour de France avec Zwift, I didn’t expect this many people on the road. Now it’s much more.”

Eleven years later the bikes are lighter, the teams have bigger budgets, and the crowds are bigger, but once again a Belgian will wear the yellow jersey as the women race up the Col du Tourmalet.

What did you think of this story?