I don’t do New Year’s resolutions. I’ve nothing against the concept of resolutions, I just don’t bother myself. It may be because my winters are already filled with daydreaming of cycling goals for the following year and plans on how to achieve them. Either way, I tend to be resolving to do something faster all the time, rather than just at this time of year.

It is, though, only at this time of year that all those goals seem perfectly achievable. As realistic as they seem now, this set of targets, usually one per month, one building on the other working towards a main objective for the year, usually whittles down to achieving just one as the realities of time, weather, and finances chip away at my annual wish list.

These goals were usually road races, so-called C and B goal races to semi-target in a build up to the main goal of a season. But recently they’ve turned to solo or endurance-like challenges. In reality, I probably dream up three or four times as many as I ever actually attempt: An Hour Record (not the actual record), various place-to-place records, new time trial PBs, gravel…. Basically anything done on two wheels with a stopwatch involved.

One such goal for the past two or three years has been an Everesting Roam 10k. The concept is as straight forward as Everesting itself: ride a minimum 400 km with a minimum 10,000 metres of elevation gain within a 36-hour period. Me being me, I set a couple more objectives of my own and set about doing it in one day as fast as possible.

I finally ticked the Roam 10k off the to-do list this year, and while there was plenty of optimisation, tech hacks, route planning, and even a short video, ultimately I ditched the “fast as possible” element of the ride as it became much more about getting it done than the time. This is the story of how I optimised the heck out of the Roam 10k challenge for 18 months, only to throw that plan out the window and, on just a few days notice, simply focus on getting it done. It’s the story of how optimising everything for the fastest time possible and not giving one hoot about time and speed can be seemingly opposing mindsets yet perfectly overlap, even if just for one day only.

Stepping stones

News Year's resolutions aside, I guess I do short-, medium- or long-term cycling goals, but rather than time measured, they are usually distance or elevation-based stepping-stone goals, small targets first in the shorter spring days, getting bigger and longer as daylight stretches deeper into evening. I’ll drop one into each month in the buildup to my overall target; a shorter target like a virtual Everesting Base Camp might drop into January. It's not something I am targeting per se, but something I can tick off as I prep for a bigger goal in, say, June. A shorter place-to-place record goes into April, while my biggest stretch goal always slots into June – just before the Tour de France madness kicks in and my fitness drops off.

But, as the old saying goes … if you want to make god laugh, tell him/her your plans. I’ve had this goal-setting approach for a half decade or more, and not once has the path I set come to fruition exactly as planned. Heck, I haven’t even got to the start line of the vast majority of challenges and events I dream up, but still, they give me focus and keep my mind alert to new ways to optimise.

It’s not that the goals are unattainable; they are SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-Bound). I am capable of achieving any of them and a goal rarely drops off my list entirely. But the realities of time and money make the process of ticking them off painfully slow for my impatient self. As such, I often turn to these stepping-stone challenges that are closer to home, and thus much less expensive to attempt, to scratch my competitive itch.

For two years the Everesting Roam 10k has been one such stepping-stone goal. I’d analysed every aspect of the challenge: the route, the equipment, and how I could optimise the whole thing to do it as quickly as possible. Here's the plan I originally put together.

Building a Roam-worthy route

Of course, the fastest way to complete 10k vert and 400 km is to separate them as much as possible. Step one could be to do an Everesting and a bit more with hill climb repeats, amassing close to 10k metres of elevation, before setting off to complete the remaining kilometres of the 400 required on some pan-flat route, ideally with a tailwind and probably on a TT bike.

While not prohibited, this repeats and TT approach does sort of miss the “Roam” element of the challenge. That said, my calculations suggest it could be incredibly fast. Theoretically I could do an Everesting on Mamore Gap (the climb I used for the Everesting record) at a pace roughly an hour or two slower than my Everesting record and then head off for a relatively flat and fast seven or so hours on a TT bike,. As tempting as this was, it wasn’t the challenge I wanted.

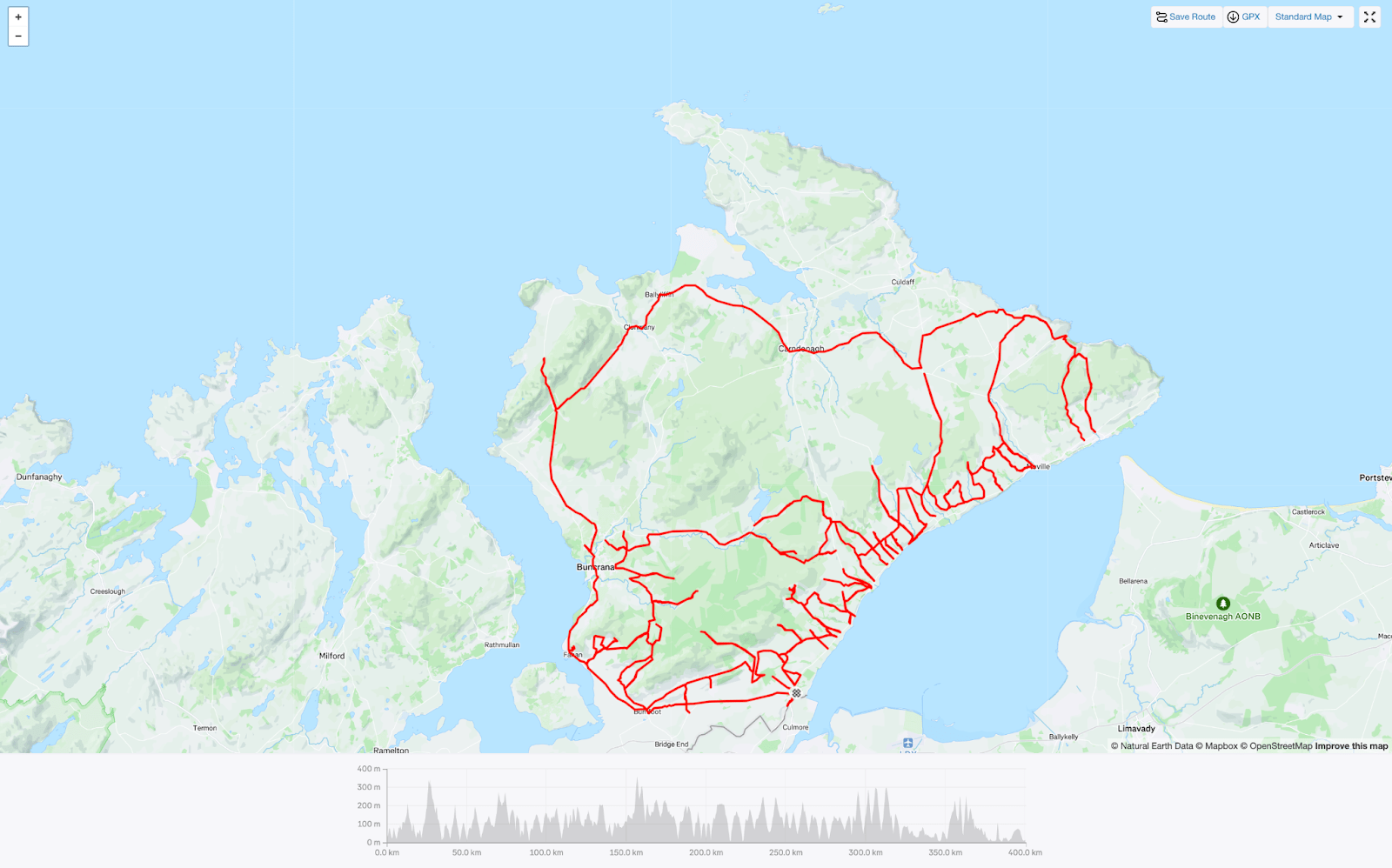

In true Roam fashion, and following a lot of consultation with Philip Rotz, a true Roam 10k aficionado who had compiled a detailed analysis of many previous Roam attempts, I set myself the target of riding 400 km with 10,000 metres of elevation gain and paired that to my own additional made-up rules that 1) I had to start and finish in the same place and 2) I couldn’t cover any stretch of road more than once in each direction.

With that simple, but massively impactful, addition to the actual rules, my Roam 10k became a much greater geographical challenge to go with the physical challenge it would always be.

In setting myself the rule of no repeats, I’d immediately ruled out an Everesting-plus-time trial type approach. I did allow myself the option to traverse a single road in both directions, but I could not then pass over that same road again at any point. In starting and finishing in the same place I excluded any option to have a net average direction route that might allow for a ride that could pick up a tailwind most of the time. And, although the Hells 500 takes each rider’s challenge time at the point they hit 400 km and 10 km vert, I wanted the start and that finish time in the same place, and so cramming those targets into a route that landed me back where I started in – with no more and no less than the 400 km traveled and 10 km climbed – became an obsession.

Luckily my home area is jam-packed with short, sharp, and steep climbs. That area is the Inishowen Peninsula, a hilly peninsula roughly 40 km (25 miles) from north to south and 30 km (19 miles) from east to west at its widest point and which contains Ireland's northernmost point, Malin Head. The fairly dense (by rural standards) road network within is characterised by mostly flat coastal roads and countless roads jutting into the mountainous centre that immediately turn steeply towards the sky. Although definitely a challenge, hitting that 10k vert target on Inishowen would be achievable.

Plotting a route crisscrossing the two main mountain ridges and as many of these steep roads and lanes to hit that target 10k vert, I realised that in front-loading as much of the climbing as possible there was an opportunity to adopt a little of the “repeat and TT” format while still sticking to my own idea of how my Roam should look.

The concept was simple: do the hardest part when I was freshest and save some easy miles for the end when I’d be struggling most. For a long time the plan even included a support car and a TT bike for the final flattish sections. In reality, it didn’t quite work out that way, but we’ll get to the whys of the mostly-unsupported attempt. I plotted and tweaked various different route options, and always factored in a little extra elevation to mitigate the risk of getting to the finish with less than 10k of elevation gain.

Ultimately, the route I settled on had me starting in my home village of Muff in the southeast of the peninsula, and centred mostly on this eastern side of the peninsula where I could tick off the climbs and clock up the elevation with very little flat roads that wouldn’t help me in my ride towards 10k.

Ticking off many of the climbs out of the village in a two steps forward, one step backward approach, I initially did a short loop around to the western side of the peninsula, briefly touching a road I would not see again for 350 km, and then back to the core of the climbing up the eastern side. The navigational challenge aspect of plotting such a route that had me tick off so many climbs – often presenting as various roads up the same mountain from various directions – without overlapping or repeating was a fun process, and immensely enjoyable on the day. The constant mental checks of the route ahead to ensure I didn’t miss a turn definitely helped the time fly, but it was only when I was 10 hours and over 200 km into the ride but yet somehow only 10 km from where I started that the ridiculousness of all it all sort of dawned on me.

The final 200 km consisted of two distinct sections. The first 100 km was pretty much identical to the first 200: Every short steep climb I could squeeze in, punctuated by super-fast descents with very little flat road. But thanks to that front-loading approach, all those sharp climbs gave way to a final 80 km with just three proper climbs, one of which was long and steady: a vast contrast to what I’d be used to the rest of the day and an opportunity to clock off the final kilometres at speed.

As a comparison, I’d climbed some 2,400 m in the first 80 km which took me some three hours and 40 minutes, whereas I had 1,000 m less elevation in the final 80 km which I thus covered some 30 minutes faster.

All that said, and despite doing some elevation gain-checking recon rides and even eking out extra elevation in climbs that extended farther up a mountain than my mapping had indicated, it was evident as I approach the final kilometres that I’d be coming up short if I stuck rigidly to my flattish final section.

Thankfully, I’d pre-prepared a note on how much elevation gain I should have at various waypoints along the route from my Strava maps for comparing to my head unit elevation numbers during the attempt and thus spotted this potential issue before it became a Roam-scuppering problem. And so, I ended up having to include an additional three nasty kickers inside the final 30 km. Turning off the flat plotted course and onto these leg breakers in the dark of night some 16 hours or more into the ride was tough, but ultimately they meant as I rolled into the village of Muff where I’d started just after dawn that morning, a quick little one-kilometre detour saw me tick off the magical 400 km and 10 km vert within metres of my starting point.

Perfect is the enemy of done

The right bike for the challenge was initially as big a problem to solve as the route itself. Typically, only aero would do for a 400 km solo ride, but with some 33% of this route on gradients of 6% or steeper, and some 50% of the ride below 20 kph, weight was definitely a bigger factor than it might otherwise have been.

I’d calculated a kilogram of weight difference would result in a +/- 3-minute gain or loss over the 400 km and 10 km vert, while a 5% aero gain in moving from a lightweight climbing bike to an aero-optimised bike could have saved approximately 12 minutes. As such, I looked at building the lightest possible aero bike, which could have been fun, but it also seemed a little wasteful to build a bike for this one challenge. For a while I’d considered dusting down the old Everesting-record Giant TCR, and – when I thought I'd have a support vehicle – a climbing bike and TT bike double act.

Ultimately, though, I went with Wilier’s new Verticale climbing bike. There were a few motivating factors behind that decision, and if I am honest primary amongst those was that it was the bike I was riding most at that time, the bike I was familiar with, the bike I had to write a review on within a week or so, and the bike I was happy and comfortable on. These factors would be critical on a lengthy bike ride like a Roam 10k.

Furthermore, I reasoned that because it is pretty light, handles well, and has clearance for large tyres it offered other advantages for the technical and rough roads I’d be riding.

But an aero bike is one thing the mostly round-tubed Verticale is not. I would be able to claw back some of the aero losses by using Syncros’ Capital SL Aero, a 60 mm-deep – but still lightweight – set of wheels. Technically speaking, the Verticale's internal brake hose routing and narrow bars would claw back some more of those lost aero gains, and I reasoned to myself the frame bag would even help a little more. But, those are all gains that could also be applied to a dedicated aero bike. Ultimately, the whole bike conundrum (along with the support crew conundrum I will get to in a bit) was a major motivating factor in the shift in focus to getting the Roam done rather than attempting the fastest time possible, I settled on the Verticale and got on with it.

That said, I did make a few "safe bet and easy done" tweaks to the Verticale to optimise it for the job at hand. I fitted Pirelli’s P-Zero TLR RS 30 mm tyres to the aforementioned Syncros wheels, reasoning that the extra width and thus lower pressures I could run would come in useful on the typically very rough chipsealed roads in the region and even a few short stretches of gravel I’d have to navigate.

I swapped out the Wahoo Speedplay Zero pedals I typically use for the Everesting bike’s Speedplay Nanogram race-day-only pedals. To be clear, this wasn’t the Wahoo Speedplay Nanos but the original Speedplay Nanos from way back in the day that weigh just 130 grams for the pair and are said to be good for just 500 or so kilometres if I remember correctly. FWIW by the end of the Roam I am up to at least 520 km on this set and yes, they are showing signs of wear.

Kit-wise, I stuck to my tried and aero-tested Met Manta helmet that has tested fastest for me in two out of three helmet tests I’ve run, but which still offers decent comfort and sufficient cooling for an Irish summer day. For clothing, I dusted down a Castelli San Remo suit, aero base layer, and aero socks. All that aero was likely lost when I added the Albion cargo vest over the top, but that was a sacrifice I was willing to make for a long day on my own in the saddle starting in low light and finishing in the dark.

As per usual for my challenges I also dusted down the Giro Imperial red shoes. The Imperials are lightweight, but the significance here is my pair's red colour. For me it’s a nod to the Red Sneakers for Oakley foundation and other charities raising awareness of food allergies, a cause close to my own heart given my daughter's severe allergies.

An eating contest of a nutrition plan

Strangely, given how long and challenging as the Roam 10k, it is the first endurance challenge like this I’ve finished and not been on my hands and knees. I didn’t even mutter the “never again” lies that I do at the finish line of most of these endeavours. A large part of that was the very steady pace throughout. I spent just 4% of the ride above my (at the time) 365 watts FTP, despite the viciously steep gradients. That was partly thanks to a strong fueling plan.

Unfortunately, with the passing of time I have lost the note of my exact intake throughout the day, but a photo on my phone of all the empty wrappers I took home shows I had at least nine sachets of Styrkr dual-carb Mix90 drink. I do wish Styrkr (and other brands) would make these high-carb drinks in tubs we could scoop powder from, but the fact they are individual sachets means I can be sure from this photo I took nine that day. At 90 grams of carbs per serving, that’s already 810 grams total. Add to that three Carbs Fuel gels and four Styrkr gels both with some 50 grams of carbs per serving, six bars with some 40 grams of carbs per bar, some isotonic gels, and a few “spuds” for some natural fuel, it was the kind of fuelling strategy that is likely the root cause (pun intended) of the operation to remove four wisdom teeth that I have scheduled for mid-January. Sugary sports nutrition is not healthy, least of all for our teeth, but it is effective for high performance.

Add to that some Haribo and a chicken wrap I ate later in the ride, and the Roam 10k was as much an eating contest as it was an endurance challenge. While that seems like an incredible amount of food, in tallying it up I was probably a fraction under what I should have had for what ended up being an almost 18-hour ride.

A rough estimate puts my intake around the 85-90 g of carbs per hour for the entire ride and perhaps scarier than the close to one kilogram of carbs is the £55 or so I spent on energy products for a single ride. Modern fueling strategies are certainly better, but oh my are they costly.

Self supported and filmed

As mentioned earlier, initial plans were to do the Roam 10k fully supported. Sherpas are permitted in both Everesting and Roam 10ks, but again there is some debate as to what extent of support is acceptable.

Ultimately, I decided to do the Roam 10k unsupported, not because I fell on that side of any debate on the merits of having a support crew or not, but simply because the practicalities of having a support vehicle and film crew were proving a detriment to actually getting the thing done. Having a support crew be ready at a day or two’s notice to follow behind me for 17 hours and, crucially, navigate a frankly quite-ridiculous route was impractical at best and an ask I didn’t want to make of anyone.

Having spent months planning, scouting and tweaking the maze-like route it made sense and all linked together in my mind but it was almost impossible to describe. Furthermore, many of the roads I’d be riding up only to turn around and ride back down again were a car-width wide at most and so there was a high probability any support crew would be way behind me delayed trying to turn and/or lost as often as they would be in close proximity to me. A crew could of course have waited at the bottom of each climb, but this seemed equally ridiculous and most of all unfair to ask of any crew.

Ultimately, much like the decision to skip a dedicated bike, I decided that while I could be faster with a support crew, I’d rather just have the Roam done and so set about planning an unsupported attempt. Truth be told, this became half the fun and opened up a whole new avenue of challenges to optimise, mostly around how to ensure I had enough food and water to sustain a 17-hour ride, and given I wanted to video document the ride, how would I shoot it alone?

The solution? An Assos Spiderbag backpack that had randomly come into my possession a few years back, a Lead Out frame bag, and a host of “drop zones" spots to stash supplies. With so much of the ride on out-and-back routes resembling branches off a main trunk, I plotted a host of locations I could drop a single bag of food and gear, ride out a trunk section of the route with a series of branch-like climbs off it before eventually returning to the same spot where I could then collect the bag again.

So, as I set off at 5:30AM for a 400 km climbing challenge, I did so with my skinsuit pockets carrying just enough food to keep me going for an hour or so, but the Spiderbag bag pack stuffed with enough food, tools, sun cream, chain oil, carb mix satchets, and even a power bank to sustain me for an entire day in the saddle. That bag was then dropped after just 10 kilometres in a spot I was due to pass again 50 km later. I repeated this process over and over throughout the ride, dropping the bag at 68, 112, 216, and 293 km and picking it up as I passed the same points after 77, 127, 225, and 326 km.

The benefit of proper fuelling was immeasurable, and I had worked out that the benefit of not having to carry those many grams of carbs around all day tallied up to minutes over the entire ride, not to mention the comfort benefits of not lugging around a backpack all day or wasting time stopping at shops several times during the ride to top up supplies. That said, I had made a note on my phone of seven shops and their position along the route in case of emergencies. As if to highlight the intricacy of the route, the first shop I’d pass was a full 220 km into the 400 km route, which was, again, all within a relatively small 884² kilometres (about 341² miles) peninsula.

As for filming the ride solo, that’s where modern technology and the wonders of editing stepped in. I shot almost all the footage from a GoPro camera with a bite guard-like mount and a Hover auto-following drone. Both lived in the Lead Out frame bag which also housed a tiny multitool, a spare tube, and a pump. The large opening on one side coupled with a smaller opening on the other meant I could stow these in-case-of-emergency spares out of sight but still quickly and easily grab the cameras whenever an opportunity to record presented itself.

With the drone this meant unfolding it and setting it loose when I was riding steep uphills where I’d be moving slower. The Hover is a little fiddly and slow to start up, but once I got in the swing of it I developed a process to it all: Open bag, unfold drone, turn it on, wait for it to wake, stop the bike, let it take off, then recommence ride. Kind of hilariously the biggest challenge to the drone was getting it to stop flying. The Hover AI is supposed to recognise a crossed arms signal as a "stop flying" notice, but quite often doesn’t pick up on this and so I end up at the side of the road frantically crossing my arms over and back trying to get it to land. Fun times!

The GoPro is a little more straightforward. I simply had to take the camera from my bag, grab the mount with my teeth, hit the record button, and it automatically starts up, starts recording and stops quickly and easily. I used the GoPro for scenic shots, descents, and some places I could simply set it down just before a u-turn in the route and collect it on my way back.

All told, with a moving time of 17 hours and seven minutes, and a total elapsed time of 17:57, it's fair to assume this self-shot filming and bag-drop routine added something in the region of 30-45 minutes to the ride (the rest of the non-moving time was nature breaks and other short stops).

Finally, thanks to the wonders of video trickery and a washing machine, I was able to head out three days after the ride and shoot some b-roll using the exact same kit and on some of the same roads I used for the Roam. We used these shots to paint the picture of how the ride fitted together but the majority of the action is from the actual Roam 10k ride.

All that said, I didn’t do the Roam 10k entirely unsupported. While I did do significant portions of it entirely solo, intentionally lost in a maze of country lanes without another being in sight, my dad did come up to see me and top up my water after five hours, and again after 12 hours, after which he drove behind me in the fading evening light from there to the finish. This was a welcome sight, especially for the chicken wrap alternative to yet another gel that he picked up from a shop along the route.

Furthermore, as the evening turned to night, Chris McElhinney, a regular in my support crew, came out to follow me up Mamore Gap and on to the finish along the mostly bigger roads where it was easier to follow.

Again, there are no rules stating the Roam must be unsupported, nor are there any rules stating it must start and finish in the same place or specifically banning repeats of the same climb. I’d added all these elements myself, and so when my dad and Chris did show up to support, they were a very welcome sight rather than any concern they could present a potential rule violation.

All told, I completed the Roam around 11:20PM after nearly 18 hours out. I’d averaged 23.6 km/h and topped out at 87 km/h. Power-wise I averaged 199 watts with a normalised power of 246w (all that coasting downhill responsible for the large delta on what was otherwise such a steady ride), average heart rate was 129 bpm, max 165 (roughly mid-Zone 3 for me), and somewhat hilariously, my average cadence was 71 (not including zeros) … yeah, there was a lot of steep climbing!

I’d taken four KOMs and a few PRs. Completed 12,200 kiloJoules of work, which with all the human efficiency and conversions applied means I roughly burned 12,000 calories, and clocked up a TrainingPeaks Training Stress Score of 838. Across the 400 km I covered were just 25 km of road I’d never traversed before, but much to my delight, by the time I got back to where I started, I’d completed a Roam quicker than anyone has ever done it and in less than half the 36 hours the Hells 500 set as the time cut for a Roam. And I’d done the fast bit with the more enjoyable and rewarding “simply get it done” approach.

Speed was not the goal for the Hells 500 when conceiving the Roam 10k concept, and arguably I could have enjoyed it much more had I taken my time even more and split it over two days as permitted.

That, though, wasn’t the challenge I wanted for myself. I know these roads, I know the area, I didn’t need to take it all in again. I wanted to challenge myself and I wanted a stepping-stone to something bigger. I certainly got that!

My previous unsupported benchmark was sub-10 hours, I’d almost doubled that. My previous elevation benchmark was an Everesting, I’d bumped that up substantially. And while neither the 400 km nor the 17 hours of saddle time were my longest rides ever, they still felt like major achievements.

I’d put the Roam off for far too long, talked myself out of it as I was genuinely afraid of the challenge, but in completing it I landed on a new stepping-stone, some 400 km in circumference and 10 km high. What does the 2025 stone look like…? Well, Lachlan Morton is a dangerous influence and that Roam stone gives me the confidence to dream if there is a stone that looks a lot like the island of Ireland.

Did we do a good job with this story?