On the eve of my 53rd birthday, I created an Instagram post based on my thoughts about the state of bicycle retail in relation to its regard for mechanics. I was full of frustration, having just resigned from a casual job as a mechanic in my local bike shop, so publishing that post was a cathartic moment. I wasn't prepared for the response, though, which amounted to a relative tidal wave of interest, support, and troubling anecdotes from around the world.

I knew I wasn't alone in my criticism of employment conditions for mechanics (and for that matter, retail staff in general) in Australia. Mechanics the world over have grumbled about it for years to the point where it has become a laughable point of conversation where we try to alleviate the misery by trumping each other with our worst experiences. Overworked, underpaid, ignored, and exploited with few opportunities for career advancement: these and other complaints are so common that they have come to constitute a sort of norm, which might explain why they have gone unchallenged for so long.

What makes this situation truly tragic is that good mechanics are passionate about bikes. We thrive on working with them and improving our skills. Perhaps the most addictive aspect is achieving that invigorating flow state where your hands take over from your mind and time releases its grasp. Whenever I think of the workshops I have shared, it's not the music or the banter that comes to mind; it's the studious quiet backed by the gentle percussion of hand tools.

If it's not yet evident, I love being a mechanic. I also deeply appreciate the industry that provides so many great products that facilitate and fuel my cycling interests. But bicycle retail has broken my heart, and that's what I'd like to discuss in more detail with the hope that it will start a conversation about improving the place of mechanics.

My experience in the industry

I started working as a bicycle mechanic in 1996, entering the profession in the same way that a lot of mechanics do, by getting a job in a bike shop. At 26 years of age, I was a late starter (due to my university studies), though by that point I had 10 years of experience from working on my own bikes. I took to it naturally, and was passionate and highly motivated, so it wasn't long before I was promoted from bike assembly to service and repair.

I was fortunate to work in a very busy store in Sydney's central business district, surrounded by a team of excellent mechanics. In terms of my training/apprenticeship, I couldn't have done any better if I'd paid to attend a world-class university; that's thanks to the generosity of my colleagues, who shared decades worth of knowledge and experience. In due course, one of those mechanics became a mentor (as well as a treasured riding buddy) to whom I owe so much, including all of my early confidence and customer service skills.

Six hundred and twenty-five dollars. That was my weekly wage in 1997. Compared to the post-graduate scholarship I had been living on for the past four years, it was an absolute bounty. But for a job that demanded up to 46 hours of work on a rotating seven-day roster, the hourly rate ($13–15/hr with no weekend loading) could only be described as meagre, but I really didn't mind. I was learning something new every week, gaining valuable experience, and on a few occasions, I was also getting the opportunity to build some sweet custom road bikes (one standout was a Merckx in team Motorola colours).

An independent mechanic

I moved to Perth in 1998, taking up work outside of the bike industry, and yet it wasn't long before I found casual weekend work in a bike shop, trading my time for store credit in order to pay for my cycling habit. I was married, and a mortgage and family were not far off, so a handful of hours each month was a fair trade for some guilt-free spending money, which I was able to accrue at the princely rate of $20–22/hr for the next 12 years.

The idea to become an independent mechanic was not my own. I had always presumed I would need to serve in a shop in order to keep working as a mechanic, so I was surprised by the suggestion from my last store manager to start my own business.

It was 2009, social media was still in its infancy, and there were no obvious role models for independent bike mechanics in the industry. It was difficult to see how it would work, but I couldn't fault my manager's ironclad argument ("Why not?"), so ended up taking the plunge early in 2010.

The Bikemason was created as a service-only business that I operated from my home, and it became a weekend side-hustle. More importantly, it gave me the opportunity to create my ideal workshop that I was free to operate exactly as I pleased. That meant offering same-day turnaround – on weekends, no less – with a flat labour rate instead of prescribed service packages so that I could tailor my work according to the individual needs of each customer.

It was a coming-of-age moment for me. After so many years of working as a mechanic in the name of somebody else's business, I was finally putting my own name on my work. Better yet, I quickly discovered that in the absence of a service manager, I could get to know my customers and provide them with the satisfaction of communicating directly with the person that was going to be working on their bike. The personal reward was immense.

The difficulties of converting part-time success into a full-time business

At $50/hr, the Bikemason was cheap compared to the local shops, so my business grew quickly. I didn't have any interest in marketing, but I had a hunch that word-of-mouth would take care of that, and after a lag of about a year, it certainly did. My timing couldn't have been better, because online shopping had matured to become a new force in the industry and its customers were always looking for a set of hands to install their new parts.

After about five years of a part-time supplementary income, I decided to abandon my day job for the Bikemason, and I quickly learned some important lessons. My overheads may have been low, but $50/hr couldn't provide any extra income for my superannuation, days off, or a marketing budget. The latter was a massive oversight, because I really needed to attract new customers at a much faster rate than word-of-mouth in order to pay my mortgage and household expenses. I muddled along for a while before I eventually got another day job, then continued to operate the Bikemason on the side.

By 2020, I had a much better understanding of how important sales is to a service-only business. I may have increased my hourly rate to $120, but every dollar was labour intensive, so there was no passive income. Had I been stocking all of the parts that my customers needed for their bikes, I would have been able to improve my profitability to account for the unpaid aspects of my job (e.g., web site, phone and e-mail enquiries, workshop tools and consumables, etc.).

Buying parts from wholesalers is not easy, though. Back in 2010, I attempted to establish accounts with Australian wholesalers, but there was simply no interest. At the time, I thought it had everything to do with being a new business, but I would eventually realise that the industry was not willing to accommodate independent mechanics. The reasons for this were never made clear to me, though over time I discovered that there are a lot of traditions in the bicycle industry that make it difficult for independent mechanics to buy parts at wholesale prices.

Some of those traditions include the provision of a storefront, stock displays, minimum monthly spends, and even a requirement to stock a major bicycle brand. Put another way, the most attractive customers for wholesalers seem to be those that have high overheads and at least some debt, which still strikes me as quite ridiculous (although I should acknowledge that at least some of the smaller distributors are interested in supporting independent mechanics).

A return to bicycle retail

By 2022, the world had changed (at least for a little while), and so had I. After spending a few years in semi-retirement, I was looking for steady part-time work in the aftermath of COVID-19 when I saw that a new bike shop was opening just down the road. With a high-profile brand backing this new venture, I presumed it would provide a great opportunity to capitalise on my experience in the industry. Better yet, I was captivated by the notion that I could do my part, as my masters had, to support and perpetuate excellence in the profession. After all, I had over 20 years as a mechanic, seven years as a technical editor for an online cycling publication, and proven success in another professional realm (amounting to almost 20 years, too).

I was offered a position as a casual mechanic without much hesitation, but the terms of employment ($30/hr, including casual loading, as set out by the Australian Retail Award) were barely adequate, though I didn't fully appreciate it at the time.

Now, I can put that number into its proper perspective by considering the effect of inflation on my hourly rate from 1997, which was about $15/hr. According to the Reserve Bank of Australia, there has been 90% inflation since then, so that junior rate is equivalent to $28.50/hr in 2022. Thus, in the eyes of my new corporate employer, my experience – a mechanic's most precious commodity – was worth next to nothing.

Had I performed this calculation at the time, I would have turned the job down. Instead, I accepted the offer, full of optimism that I wouldn't need long to prove my extra value and perhaps find a better position within the business.

My optimism was never rewarded. My corporate employer was crying poor due to a slowing in sales post-COVID-19 (an inevitable correction that seemed to have taken the company by surprise) and I had overlooked just how much the business was focussed on product delivery (i.e., new bikes). I was given several opportunities to be heard, and one or two carrots were dangled, but the message remained the same – take it or leave it – and there was every indication that the rest of bicycle retail was in the same mood.

I found some solace in the work, but this could not resist the full weight of my growing disenchantment, which culminated with my resignation after just nine months (one of my shortest appointments ever). In the end, it was disappointing to feel that experience and expertise – not just mine, but in general – wasn't being rewarded, it seemed, by the local industry as a whole, and not just my particular corporate employer.

In the aftermath, I struggled to understand how bicycle retail could be so cavalier and exploitative. After all, it is entirely dependent on competent mechanics for providing safe and reliable stock for the salesroom floor as well as generating workshop profit. Such indispensability is normally richly rewarded where company executives are concerned, and there are industries that value skilled labour (which are currently luring mechanics away from bicycle retail).

At the very least, I expected more from my former corporate employer, which insisted it had a high regard for excellence and spoke bravely of playing the long game. Then the penny dropped, and I realised (with some embarrassment) that I had been blind to just how ruthless it, and the rest of the retail bike industry, can be when it comes to managing its costs.

Bicycle retail: a nice place to visit

For a novice mechanic, it can be relatively easy to enter bicycle retail. There is no need for any kind of certificate, and at least some shops are prepared to devote a few months of on-the-job training to improve a novice's skills. This is feasible, because the fundamentals of bicycle assembly are easy to pick up by anybody who has some mechanical aptitude, and for the business, it is cheap labour. In the first instance, this is a pretty fair trade, but I suspect it accounts for the prevailing attitude of bicycle retail (and the poor esteem of the profession): get them cheap so you can keep them cheap.

The path in bicycle retail for the career development of a mechanic is anything but clearly defined, particularly in smaller shops that don't have the luxury of a separate position to oversee the department. Within the workshop, an assembler can strive to be promoted to service and repairs, but beyond that, a mechanic must often be prepared to take on other duties that have little to do with their expertise (e.g., customer service or management). Some businesses may recognise and pay extra for a senior mechanic, but the value of their hard-won experience often goes unrewarded, at least when it comes to money in hand (or a share in store profits).

There are some perks to being employed in bicycle retail, and a staff discount is the biggest of them all. A qualifying period must normally be served to earn the largest discount, but in some instances (my former corporate employer being one), there are other conditions, too, such as permanent employment. Other perks include borrowing from the store's fleet of demo models (if one exists), and on occasion, valued employees may be rewarded with a bike.

Clearly, there is not a lot of incentive for a mechanic (or sales staff, for that matter) to stay in bicycle retail beyond a certain point (at best, 3–5 years), which probably explains why it is unusual to encounter a middle-aged mechanic in this space. I can't help but bristle at this notion, because at the very least, customers are often drawn to older (and wiser!) staff in the workshop, if only because they can provide a more assured space than junior employees to discuss their needs and concerns.

However, there is another, more important, reason for bicycle retail to retain experienced mechanics. Every workshop needs an experienced mechanic to establish and uphold its standard of workmanship. At the same time, that mechanic can provide ongoing training for junior staff and step in with advice when challenging jobs come along. In this regard, the Internet and its plethora of videos and instructional articles are valuable, but there is no substitute for learning at the feet of a master. Without it, there is an enormous risk that shoddy work and bad habits become accepted practices, ultimately undermining the reputation (and profitability) of the workshop.

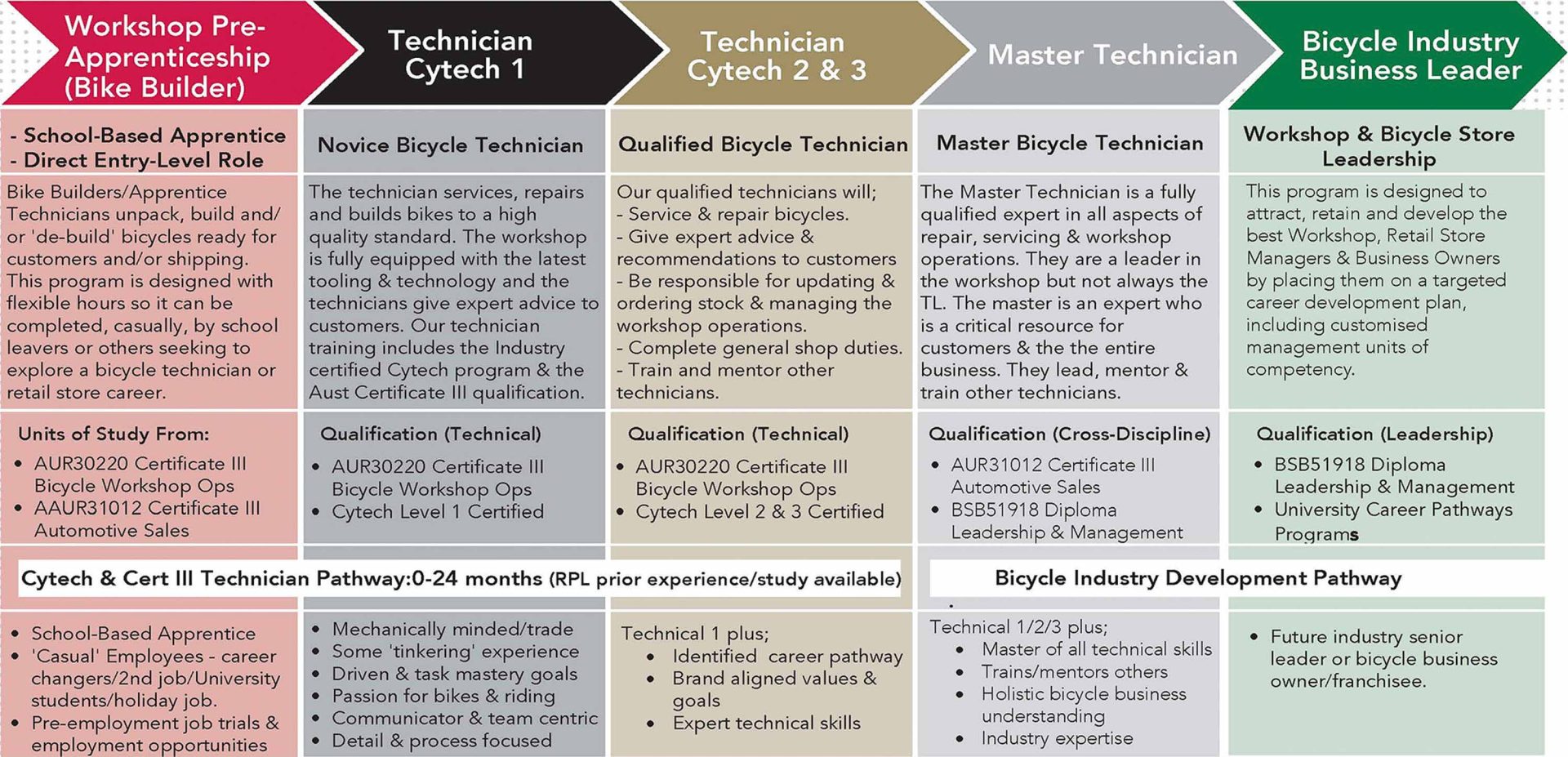

A common suggestion for improving the standing of bicycle mechanics is formal training and accreditation. Cytech, an organisation created by the U.K. Association of Cycle Traders, has been providing both for the last 35 years, but based on published wage ranges (starting, £20K; experienced, £30K), there is still a low ceiling for what the U.K. industry is willing to pay.

The Bicycle Academy recently brought Cytech's training and accreditation to Australia, and has even developed a local apprenticeship scheme, adding a fresh avenue for novices to enter the industry. It is far too early to judge the impact of this initiative, but that it acknowledges the importance of workshop experience to the success of its training is a good sign. Unfortunately, the academy does not currently provide a streamlined accreditation process for mechanics already working in the industry, which seems like a missed opportunity, but this might simply reflect the fact that experienced mechanics won't see any value in it. After all, there is no incentive for such accreditation, so why would they, or their employers, pay thousands (or even hundreds) of dollars for it?

Based on current employment conditions, I find myself thinking that the prospects for a professional mechanic are similar to those of a professional athlete. Both thrive on passion and demand an incredible amount of devotion, but ultimately, the long-term rewards for each are vanishingly small. In this regard, I have to applaud Drapac Cycling for its frank acknowledgement of the limitations facing professional cyclists by supporting vocational training in other realms. This is the kind of initiative that a large corporate retailer could commit to, though I doubt it will ever happen.

Instead, the best that can be done at the moment is to speak openly and honestly to mechanics starting in bicycle retail so that they can create and pursue opportunities that will benefit them upon their inevitable exit.

I have a dream...

My recent experience in the retail bicycle industry may have left me disheartened and more than a little cynical, but I still feel proud to be a mechanic and I'm optimistic about the future for bicycle mechanics. The simple bicycle is a thing of the past, and they will only become more sophisticated in the future. I count this as a good thing because I'm sure many mechanics will enjoy the challenge of mastering each new generation of bikes.

The retail bicycle industry needs to find a way to improve employment conditions for mechanics, because all of this extra sophistication has to be mastered for a shop to retain its credibility and trustworthiness. Perhaps this will be the trigger that thins out an overpopulated herd because it is not the sort of thing that can be faked.

Great mechanics are curious self-starters, knowledgeable autodidacts, tenacious problem solvers, and they enjoy hard work. They cultivate their experience like fine wine and bank it for a massive return on a regular basis. They are often model employees and an invaluable asset to the industry, retail or otherwise.

Perhaps the most important step toward improving their situation is that mechanics start demanding more from the industry – and, ideally, that more shops begin recognizing their importance. Some have suggested a union will give them this strength, and maybe it will, but only once they can acknowledge their value to themselves, their peers, and their employers.

I also hope that manufacturers and distributors throughout the industry improve their regard for independent mechanics so that they can establish and build their own businesses outside of the traditional retail model. I see enormous potential for this approach, because it finally gives mechanics the ability to directly profit from their skills, though this may depend upon formal accreditation. Business coaches and small business associations may have an important role to play in this process, too, because mechanics are generally not gifted entrepreneurs (as my backstory clearly demonstrates).

I also see enormous potential for collectives that bring together specialists to build a business much greater than the sum of its parts. Such ventures will require a buy-in from all partners, and therefore more risk, but for those that are prepared to accept it, a mechanic can finally enjoy an equal share of the collective's profits. This is an incentive far greater than any currently provided by the industry.

As for my story, my recent experience has taught me a lot, and I cannot see myself ever returning to bicycle retail.

Did we do a good job with this story?