It feels like a life ago, but I first came across Jon Partington in a dimly lit corner of the Handmade Bicycle Show Australia. It was 2019, and there sat prototype samples of a unique boomerang-like carbon fibre spoke design as the centrepiece to a 1,150 gram road wheelset that held ambitions of being as desirable to disc-brake bikes as Lightweight’s once were to rim brake bikes.

Situated next door to the CarbonNexus hub of Deakin University (a shared collaborator of Carbon Revolution, creators of leading carbon car racing wheels), it would be another couple of years before Partington would have those feathery wheels on dreamy show bikes and under a few hundred customers, many of whom could afford to ride whatever they could dream of.

Fast forward to 2023 and the boutique manufacturer from Geelong, Victoria, has now released a second iteration of its wheels – the MKII R39/44. I’ve had these highly stiff and lowly massed carbon-spoked wheels bolted into a handful of different road bikes over the past couple of months, and while they’re unquestionably an incredible product, as you’ll find out, only a select group are likely ever to experience them.

This in-depth review looks at the tech (for which there is plenty), asks (and answers) some candid questions, and provides some back-to-back ride testing.

Good stuff: Impressively stiff and light but not harsh, easy and non-restricted tyre fitment, smooth rolling hubs, ride warranty, classy aesthetics.

Bad stuff: Top-tier pricing, proprietary everything with limited wheel repairability, wide spokes make the wheel feel deeper in high gust conditions, sharp spokes require care when handling, no aero data.

The specs

Partington is a small company (currently) with a single product for sale – the MKII R39/44. Built for racing and/or daily use, it’s a disc-brake-specific, tubeless-ready road wheel with a 39 mm depth front rim and a deeper 44 mm rim out back.

Both front and rear rims share the same 21 mm internal width with hooks for keeping tubeless or tubed clincher tyres in place. Externally, the tightly radiused U-shaped rims measure 28 mm at the widest point (at the tyre bead). A rim of this internal width is ideally suited to 25-32 mm tyres, but it can handle wider, too.

The rim beds are solid with no spoke holes to cover (yay for trouble-free tubeless!). The closed design sees Partington mould its carbon rims around a solid (machined to shape) foam core that remains in place. It’s a method that’s closely comparable to how Corima, Lightweight, and Mavic’s Cosmic Ultimate wheels are produced, and it helps to ensure tight/even compaction of the carbon while providing a further structural element.

Bonded into the rims are Partington’s true signature piece, its boomerang-like spoke design. Each moulded carbon fibre spoke is effectively two spokes, following a straight line from the rim, wrapping around the unique hybrid aluminium and carbon fibre hub shell, and then continuing on another straight path to a different point on the rim.

According to founder Jon Partington, spokes are a perfect application for using carbon fibre as they’re under tension. “The challenge is really at the junction, so the spokes at the rim or the spokes connecting to the hub," he said. "The idea by the spoke-to-hub joint is that instead of trying to terminate the end of a spoke and anchor it there, we rather just keep the loads in tension, wrap it around the hub, and then back to the rim. That way, you’re only fighting the bonding challenge at the rim.” It’s a concept that’s loosely shared by others, such as Lightweight, although the specific execution is noticeably different.

“The way we manufacture them is proprietary to us, and the spokes as they exist in the wheel are as they’re moulded with no further sanding or paint," Partington said. "One of the opportunities in the process we use is with Towpreg. Towpreg is a bundle of [carbon fibre] filaments already impregnated with resin, we gather several of these bundles, create a preform, and then mould it. And because we don’t do any post-mould finishing, each of these thousands of carbon filament remains preserved from end to end, so we get a really consistent product in terms of stiffness and strength.”

The rims, the centre of the hubshells, and the matching carbon spokes are manufactured in Partington’s own Geelong-based facility. New for the MKII, those spokes now wrap around Partington’s own hubs, with the centre of the hub being moulded carbon bonded to aluminium pieces (which are machined and finished by producers in nearby Melbourne). The wheels are only available to fit now ubiquitous 142x12 and 100x12 frames, with freehub bodies available for Shimano (HG11) and SRAM (XDR) groupsets, with Campagnolo (N3W) currently in the works. I’ll come back to these hubs.

As we’ve seen from numerous manufacturers in the past, using carbon fibre in this application aims to achieve a significantly stiffer wheel at a lower weight. And lower weight these are, which also lends itself to a claim of class-leading stiffness to weight. My test sample wheels weighed 543 (front) and 622 (rear) grams, without the provided aluminium tubeless valves or disc rotor lockrings, but with the heavier Shimano HG11 freehub body (SRAM XDR freehubs are a few grams lighter). That’s a paired weight of 1,165, five grams more than claimed weight.

How Partington stack up to other roughly similar depth and clincher/tubeless wheels (note, not all weights are verified. Prices are from the time of publishing.):

| Wheel | Rim Depth | Internal Rim Width | Weight | Price |

| Extralite Cyberdisc 338CS (Berd spokes) | 38 mm | 18 mm | 1,005 g | Approx US$3,500 |

| Princeton Carbon Alta 3532 | 32-35 mm | 21 mm | from 1,094 g | US$3,995 |

| Partington MKII R39/44 | 39 mm F/ 44 mm R | 21 mm | 1,165 g | US$6,400 |

| Syncros Capital SL | 40 mm | 25 mm hookless | 1,170 g | US$4,200 |

| Lightweight Obermayer Evo | 48 mm | 18.2 mm | 1,230 g | US$8,695 |

| FarSports Evo 4 | 45 mm | 19 mm | 1,230 g | US$2,400 |

| Campagnolo Hyperon Ultra | 37 mm | 21 mm | 1,240 g | US$4,100 |

| Zipp 353 NSW | 45 mm | 25 mm hookless | 1,255 g | US$4,220 |

| Mavic Cosmic Ultimate 45 Disc | 45 mm | 19 mm | 1,255 g | Approx US$4,600 |

| Roval Alpinist CLX II | 33 mm | 21 mm | 1,265 g | US$2,650 |

| DT Swiss PRC 1100 Mon Chasseral | 24 mm | 18 mm | 1,266 g | US$3,733 |

| Cadex 36 Disc | 36 mm | 22.4 mm hookless | 1,287 g | US$3,200 |

Partington may not be outright winning the weight wars, but consider rim widths, rim depths, and validated testing, and the Partingtons and its nearest big-name competitors are rather impressive. Meanwhile, Partington has teased that a shallower depth and 100 gram-lighter version of its wheels are near completion.

Whether we admit it or not, aesthetics play a large role in any premium purchase. I feel that Partington holds an advantage here with an understated look that lets the technology (the spokes) be the definitive visual feature. The rims are painted matte black, the carbon spokes and centres of the hub shells are left raw from the moulds, while aluminium portions of the hubs are given an anodised finish with laser-etched logos. It’s looked great on any bike I’ve equipped them to.

Now I get to the part that will surely turn away a large number of you – a pair of Partington MKII R39/44 retails for the following:

- US$6,400, excluding tax

- AU$9,900, including GST

- €6,000, excluding tax

- £5,400 including VAT

Yep, these are big figures that will only appeal to a select group. And yes, there is a market for such things, especially given that in many regions a pair of Lightweight Obermayer Evos costs more again (almost 25% more in Australia).

Such pricing may have you assuming you also get the world’s fanciest wheel bags, a coffee table book, and perhaps some cool branded toolkit. Rather, Partington focuses on the wheels and only includes a pair of nice-quality aluminium tubeless valves, aluminium centerlock lockrings, and a couple of branded cotton bags in place of bubble wrap or the like. That’s it. There’s no extra waste in shipping these wheels, but equally, no added bonuses.

There’s no denying that such pricing makes the Syncros Capital SL and Cadex 36 Disc look like a screaming deal at approximately half the price, and surely Taiwan manufacturing efficiencies help there while Australian labour rates don’t. Regardless of whether they’re worth more than the insured value of my car (they are), what matters to those who have the means to buy them is whether they do what they claim and how well they do it. I’ll get to that, but first, let’s look at some finer details.

Solving first-iteration issues

Fundamentally Partington’s new MKII isn’t a huge departure from the MKI. The carbon rims and unique spoke design are effectively the same. Likewise, the way Partington tensions and then bonds its wheels in a fixture (a process about which it’s real hush-hush) hasn’t changed. Things differ with a new in-house hub design and a new resin formula for bonding the spokes into place.

It’s commonly expected to find teething issues in the first iteration of any new boundary-pushing product, and unfortunately, that proved true for Partington’s MKI wheelset. While some of those first wheels are still out on the roads and without issue, I’ve heard from other early adopters who experienced persistent creaking noises.

“This was a real painful problem for us, and is one that we got the hardest time on. The creaking of spokes was when the spoke to hub was debonding. Because we bond the spokes to the hub, we need a particular surface finish with a different sealing method to normal which allows us to bond to it,” explained Partington with an unexpected level of openness. “Somewhere along the line, the finish of our (MK1) hubs changed from our unique specification and we only realised once the product was in the field. You’re talking about the chemical make-up of something within the surface of it, so it’s really hard to know. We only discovered this retrospectively because as far as we knew nothing had changed.”

“Our hubs are now machined locally in Melbourne, but we’re now mindful that processes can vary and there’s a risk factor," said Partington. So we produce test coupons that go to hydroblasting, they go to the anodising at the same time as the hubs, and then go to the laser engravers. [They then] go through all of the thermal cycles here, and get bonded together with the same resin as what we use in the wheels. And then we break these coupons at the end to see the failure load. It’s the most direct insight we can get for the bond without destroying the wheel to find out. We do this 100% of the time for all of our wheels.”

Partington previously used a commercially available resin to bond its wheels, but MKII wheels are made with a proprietary resin. “The challenge is that we have a highly loaded bonding joint, but also they’re very visible. The spoke to hub is plain to see, and similarly at the rim, when we put the wheel together it’s a pre-painted rim and we don’t want to spoil that finish,” explained Partington.

“We’re pretty lucky to be next door to Carbon Nexus at Deakin University who specialise in resin formulation, and so we had an opportunity to do a (paid) scope of work with them and detail our requirements. It was a huge scope of work, and we’ve now got more than twice the cohesive and adhesive strength than the original resin, better thermal tolerance, it’s easier to process, and it cures in about a fifth of the time.”

Partington seems confident the issue is in the rearview mirror. “We have internal testing for this, and we have some early prototypes which we consider good wheels, and we have later MK1 wheels which we call bad wheels. We developed a test protocol, where a full wheel mounted with a tyre (static, not rolling) is loaded at an alternating angle and given a torque input, it’s all done at a factor of two higher than what you’d deem real conditions, or potential max power under a track sprinter. This is then repeated for 10,000 cycles.”

According to Partington, this test, which simulates the forces put through a wheel when sprinting or out-of-saddle climbing, tears up the tyre's carcass and greatly flexes the very stiff wheel. The company says its original MK1 wheels with the correct hub surface finish got 50% through this test before showing signs of bonding failure. The known-problematic MK1 wheels saw the bond fail within 10% of the test; the wheel stayed together as the spokes mechanically constrain the hub, but it sounded awful. [Whereas] our new MKII we can do the full test without any signs of issue.”

While the above test is more about ensuring creak-free riding, the wheels do pass both the UCI and ISO testing standards. Jon Partington says they pass these tests by more than 200%. The wheels carry a common system (rider plus bike) weight limit of 110 kg (242 lbs).

On safety, I enquired what would happen if a spoke were to fail while riding. According to Partington, as the structure is bonded the wheel could still be ridden (although certainly not indefinitely); however, you would expect to see the trueness go out by a few millimetres.

Partington previously claimed repairability with its carbon wheels but changed its tune. Like most carbon components the wheels are possible to repair, but Jon says its an arduous job as returning the wheel to perfect trueness is near impossible.

Instead, Partington offers a two-year crash replacement warranty that will cover the replacement of its wheels if damaged in a bicycle crash, smacking into a pothole, or a similar riding-related incident. However, you may need to discuss special crash replacement pricing if you drive your bike into the Golden Arches after a ride.

On the topic of trueness, it’s up to Partington to make these wheels perfectly straight during the initial bonding, and there’s no way for a user or mechanic to improve on that further. I measured my sample rear wheel as having just a .3 mm run-out (yes, there’s a decimal point there). It’s enough that you can see it on a truing stand, but not something you’ll ever feel on the road (especially given the rim isn’t your braking surface). I feel this is understandable given that Partington does no finish work after bonding, but those expecting the laser-straight perfection of a meticulously hand-built traditional wheel may be disappointed.

A new hub

The other major update is seen within the hub. Previously using DT Swiss 180 internals, Partington’s MKII wheels move to the company’s own design, a design that Jon Partington is passionate about given a career of automotive powertrain engineering. So much so, Jon wrote a white paper on his approach to bearing architecture (soon to be live).

In a nutshell, Partington believes there’s an adverse condition that happens to many bicycle hubs when they’re loaded in a frame and compressed by the thru-axle. “You get an unwanted loading of the bearings that’s hard to detect as when you’re driving it from the rim you have a big lever working against it. However, it hides this condition and explains why many hub bearings experience premature wear.”

Perhaps exacerbating this issue is that Partington’s unique wrapped spoke design squeezes the hub shell, whereas just about every other wheel design sees the hub shell expand under spoke tension. And speaking of the MK1s, the bearing placement was directly inline to where spokes compressed. “It had a significant influence, it would shrink the housing by 15-20 microns in diameter which is almost the total internal bearing clearance," he said.

To distil a half-hour conversation into a few paragraphs, Partington didn’t just move the bearing placement but also changed the hub design to utilise an axle where only one side is shouldered and therefore the bearing inner races are not constrained to the outer races. The goal is to give different bearings different tasks in what loads they handle (axial vs radial). Related, the design aims to avoid excess preload which would otherwise prevent the deep-groove cartridge bearings from freely reacting to the common angular loads placed on a wheel.

Partington’s hub design doesn’t allow any adjustment to the bearing preload, which is set based on the manufacturing tolerances. And because Partington has designed the bearings to roll without hindrance, there is a tiny amount of detectable play at the rim. “We’re talking +/- .1mm, and you can feel it [wiggling the rim), but if you think about it in the context of the size and shape of everything that’s moving it’s trivial," he said. Indeed the play doesn’t present itself when riding the wheels, and as Partington explained, the amount you feel at the rim is magnified by distance of the rim from the axle, and the distance between the two bearings. Partington claims there are just 10-15 Microns of internal clearance on both bearings, a figure multiplied by 10 to 12 by the time it’s measured at the rim.

“In contrast, without the clearance and if you force the bearing to run in its groove while forcing it sideways, it would be trying to climb a very shallow ramp and it wouldn’t take much axial force to push it into a high contact load," claimed Partington. "The deep-groove ball bearings need some clearance to run up the side of the race.”

Those hybrid ceramic bearings, made by CeramicSpeed to Partington’s own specifications, differ in sizes depending on the role. As the most-loaded hub bearing of a bike, the driveside hub bearing on the rear wheel is made much larger to handle the radial loads, but also because its placement behind the ratchet ring makes it harder to service. “This bearing is designed to be effectively service-free, and as a result, it’s the only bearing to have full-contact seals (the other bearings have lower resistance light contact seals).”

While that larger bearing is designed not to need touching, it is still technically serviceable but with an obvious caveat – it’s trapped by the drive ring which requires a proprietary tool for removal. I also ran into other servicing quirks through difficulty in removing the snap ring that retains the left-side bearings on both front and rear wheels (future batches will have a small cut-out that allows easier tool access to get behind this snap ring). Similarly, the bearings in the freehub body are blocked by an affixed ratchet ring and are not intended to be readily replaced. Rather Partington intends the whole freehub to be replaced as a unit. While I’m not one to encourage waste, it isn’t too different to what the likes of Campagnolo (and Fulcrum) and Shimano officially recommend with its hubs.

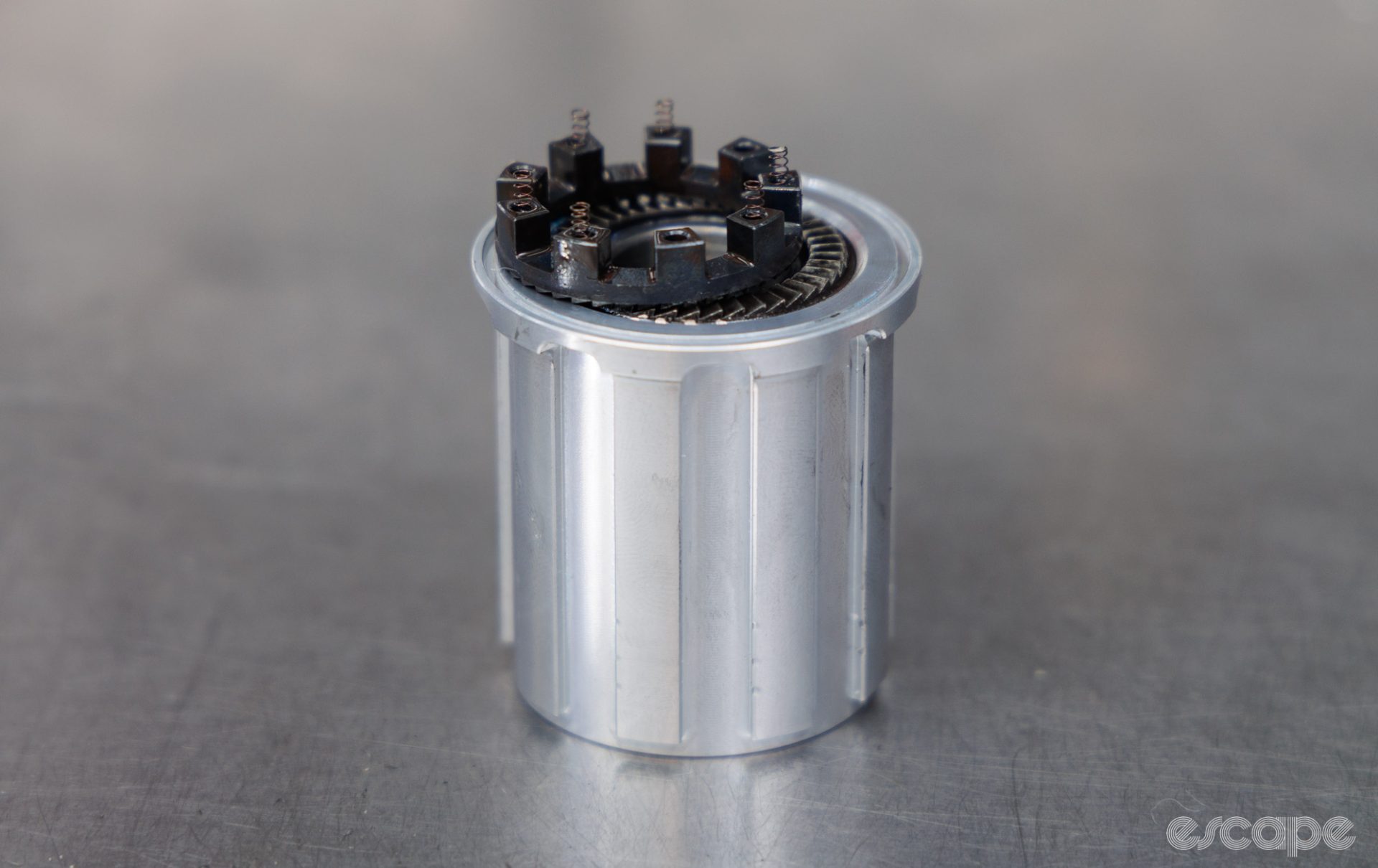

That ratchet ring is comparable in concept to DT Swiss’ Star Ratchet EXP system or a swath of other hubs that use a pair of interlocking tooth ratchet rings. Partington’s approach feels more petite, with a series of teeny-tiny compression springs providing only a light force to encourage the one-sided floating 42-tooth ratchet mechanism to engage when driven forward. Here, the hub is certainly audible but not obnoxious when coasting, and combined with the bearing design, it’s one of the fastest (lowest backdrag) freewheeling hubs I’ve felt.

The good news is that giving the freehub mechanism a basic clean and re-lube is simple. Like DT Swiss’ design, you pull on the freehub body (or cassette) to dislodge the end cap and expose the freehub internals. I didn’t have issues with the tiny springs dislodging themselves, but as always, take care.

How they ride

Getting tyres setup up on the Partington rims is nothing but a pleasure. The tyre bead and rim sizing feels extremely close to the likes of Shimano's wonderful fitment, and so I was able to install and even remove a handful of different tubeless tyres without the need of a tyre lever. And most clincher tyres will be even easier.

From the first pedal stroke, the stiffness of these wheels transform how a bike feels. It’s a sensation of having a more direct connection between your chain and the rear tyre, or your handlebars and the front tyre, and it’s a common feeling across other carbon-spoked wheels such as those from Cadex and Lightweight.

Add in the feathery weight, and these wheels truly bring a lively and reactive feel to any bike they are bolted into. Coming from a medium-depth 24-hole steel-spoked wheelset, the Partington’s truly shine in out-of-saddle accelerations and climbing where it feels like the wheels don’t stray from the line of your frame. And flat-out power sprints feel … chefs kiss.

Straight from the box, I can’t recall if I’ve ever felt a hub roll and freewheel so obviously without drag, and that was before it was worn in. On the bike, this is just another detail that helps to make these wheels feel so fast. Another benefit to such a free-spinning freehub is that you’ll never experience chain droop from where the speed of the cassette momentarily overtakes that of the chain when relaxing from the pedals for a corner.

With a relatively small ratchet ring and low spring forces, the freehub spins with a non-offensive noise level. Your friends (or competitors) will certainly hear when you’re coasting, but you’ll still be able to hear yourself think. I’d put the noise more in the range of a lightly greased DT Swiss Star Ratchet, and certainly nowhere near the racket of a DT Swiss EXP hub.

Perhaps where the wheels surprised me most was in the ride quality. These wheels provide incredible lateral stiffness (the rim doesn’t stray from the line of the hub), they also have high hoop stiffness in the rim to resist compression and loss of spoke tension under high-pressure tyre inflation. And yet, they somehow remain surprisingly smooth over inconsistent surfaces.

I didn’t trust the sensation at first, and so set up some back-to-back testing between the Partington wheels and another carbon-spoked wheel in the form of Cadex’s 36 Disc. To reduce downtime in swapping wheels, I set all the wheels up with the same Goodyear Eagle F1 28mm model of tyre (which inflated to have near identical measured widths), and even shimmed the disc rotors for speedy swaps. From here, I used a local road descent that offers some fast straights and corners over a generally poor surface.

While subtle, the Partingtons do roll with a wonderful sense of efficiency and smoothness over lightly rattly surfaces. By contrast, the Cadex wheels feel that little bit stiffer in every sense, which also translates to feeling more of the road through the bike. Meanwhile, larger and more square-edge ripples in the road felt just downright harsh on the Cadex, and while they still weren’t pleasant on the Partingtons, they were at least a little more muted.

On perfectly surfaced roads, stiff wheels like the Partington and Cadex enhance a bike's handling and make descents all the more enjoyable. Have you ever heard the tired cliche of a bicycle handling like it’s on rails? That rings wholly true here.

However, there is certainly a trade-off to such stiffness, and that’s felt when cornering on roads rippled from years of tree roots and water run-off. Here, I prefer a more flexible steel-spoked wheel over a carbon-spoked one with such incredible lateral stiffness. The former offers some forgiveness and even suspension to the uneven surface, while the latter transmits that stiffness and forces the wheel to bounce. Again, the subtly less stiff Partingtons feel ever-so-slightly better mannered than the Cadex, but there’s still a trade-off to a more-flexible steel-spoked wheel.

The only other quirk I detected was while descending in gusty conditions. Here – and despite Partington specifically stating the front wheel shape and size was optimised with handling in mind – I still felt the front wheel catching in the wind and having the effect of stiffening the bike’s steering. In this sense, the wheel feels more akin to something of a greater depth, and I speculate that the wider spokes are the cause. Interestingly I didn’t get the same sensation with the Cadex 36 Disc.

Speaking of the wind, aerodynamics is one area where I can’t provide any useful insight or worthwhile data. And while Partington did design its wheels to be more efficient than its direct competition (Lightweight), the small company hasn’t done comparative wind tunnel testing.

With a 28 mm external rim width, Partington states its front wheel is at its aerodynamic optimal with a 25 mm front tyre (where it meets the popular 105% rule). Interestingly, the company takes an approach seen previously with Canyon/DT Swiss by recommending a wider 28mm tyre at the back, or even wider again for heavier riders. Of course, the choice is yours, and I did all of my testing with 28 mm tyres front and rear.

And finally, there are the elements of owning a wheel that perhaps matter most when not riding them. As mentioned, Partington’s aesthetically pleasing and muted design looked great on every bike I put them on, but the design also lends itself to easier cleaning. The rims and hub flanges lack the usual grim-hugging nooks, and the raw glossy finish of the hubs is easier to keep clean, too.

However, care is needed around those thin-bladed spokes. I accidentally glanced my fingers across them at one point and nicked some skin in the process. And certainly, they’re not a spoke I’d want to get a limb stuck in while actually moving at speed – but I’d say the same about any bladed spoke, regardless of the material.

Carbon spokes are incredibly strong, but their kryptonite would be an inward (or outward) force applied at the spoke's centre (like laying the wheel flat on the ground and standing on the spokes). As a result, and given replacing a spoke is off the table, it’s the sort of wheel that triggers a cold sweat at the idea of stacking bikes up against a wall with pokey pedals everywhere. And the same level of stress would apply if you were to pack these into a less-protected travel case. This is certainly a benefit to a wheel with replaceable carbon spokes such as the Cadex, but beyond such concerns, nothing would stop me from wanting to use the Partington wheels as a daily driver.

Wrap up

For many, it’s the price that will prove the biggest talking point of these wheels. High-end cycling products at this level are a case study in both diminishing returns and Veblen goods. There are many examples of bikes on the market where the price is almost irrelevant and out of reach of the masses (for which, I am), and these wheels are unquestionably in such a category.

When reviewing a bike, if I’m sad to see it go or if I like my own bike a little less after the test then that’s usually a strong indication of a great product. In testing these wheels, I’ve been left with such a feeling of loss. I don’t believe being back on my steel-spoked wheels has cost me anything repeatably measurable in terms of speed, but I sure miss the aesthetics and ride feel that the Partingtons provided.

Add in the easy tyre fitment, non-annoying hub noise, and the way they feel under power, and the Partington MKII R39/44 are the best mid-depth road wheel I’ve ever ridden. Sadly, I can’t (yet) say how they compare to the latest Syncros Capital SL, Mavic Cosmic Ultimate, or Lightweight Obermayer Evo, but what I can say is that none of those other premium options offer internal rim widths that excite me for use with 28-30 mm road tyres. Meanwhile, regular-spoked road wheels that are even lighter scare me for use with tubeless.

It may have taken the industry a decade, but extremely lightweight disc-brake road wheels capable of everyday use are now here. While not the very lightest or perhaps most aero (such as the Syncros Capital SL Aero), at least in my eyes, the young Aussie company has set a new benchmark for a boutique product to match similarly high-end bikes, one that provides an equal level of polish, keeps tyre choice open, and doesn’t hamper ride quality.

The wheel market is a fast-paced one, it’ll be interesting to see where Partington and its competitors take it next.

Did we do a good job with this story?