The wind shell you pack as insurance. The chain lube that keeps your drivetrain silent. The tent that shields you from a storm on a bikepacking trip. There’s a good chance they all contain PFAS – per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, also known as forever chemicals.

PFAS have been a staple of the outdoor and cycling industries for decades. But as research into their negative environmental and health impacts grows, regulations are forcing brands to confront the uncomfortable truth: they’ve relied on toxic chemicals to achieve product performance goals for decades.

While brands' shift towards PFAS-free products has been met with enthusiasm, these alternatives are frequently criticised for not performing as well as the old, almost too-good-to-be-true coatings and membranes we’ve grown accustomed to. At the same time, with consumers becoming increasingly conscious of sustainability, slapping a “PFAS-free” label and touting the use of recycled materials has become an effective marketing tool. Yet, the reality is that even if a product is labeled PFAS-free, proving that definitively is nearly impossible.

The reliance on these chemicals has left the cycling industry in a bind. PFAS were never completely necessary, but they were so convenient and excellent in performance that they were overused for decades at nearly every part of the supply chain. Now, under pressure from both consumers and regulatory authorities, they are in a difficult race to clean up their supply chains and develop alternatives that match PFAS' performance.

Understanding PFAS - what are they?

PFAS are a complex group of synthetic chemicals that feature carbon and fluorine atoms linked together. There are almost 15,000 distinct PFAS substances known to be in use. This complexity makes them notoriously difficult to regulate. What makes them so effective – the strong carbon-fluorine bond – also makes them incredibly persistent in the environment, earning them their ominous nickname.

In cycling, they’re found in everything from durable water-repellent (DWR) coatings on jackets to friction-reducing PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene) in chain lubes, bearing greases, frame coatings, and electronics. Heck, even the band of your smartwatch may have them.

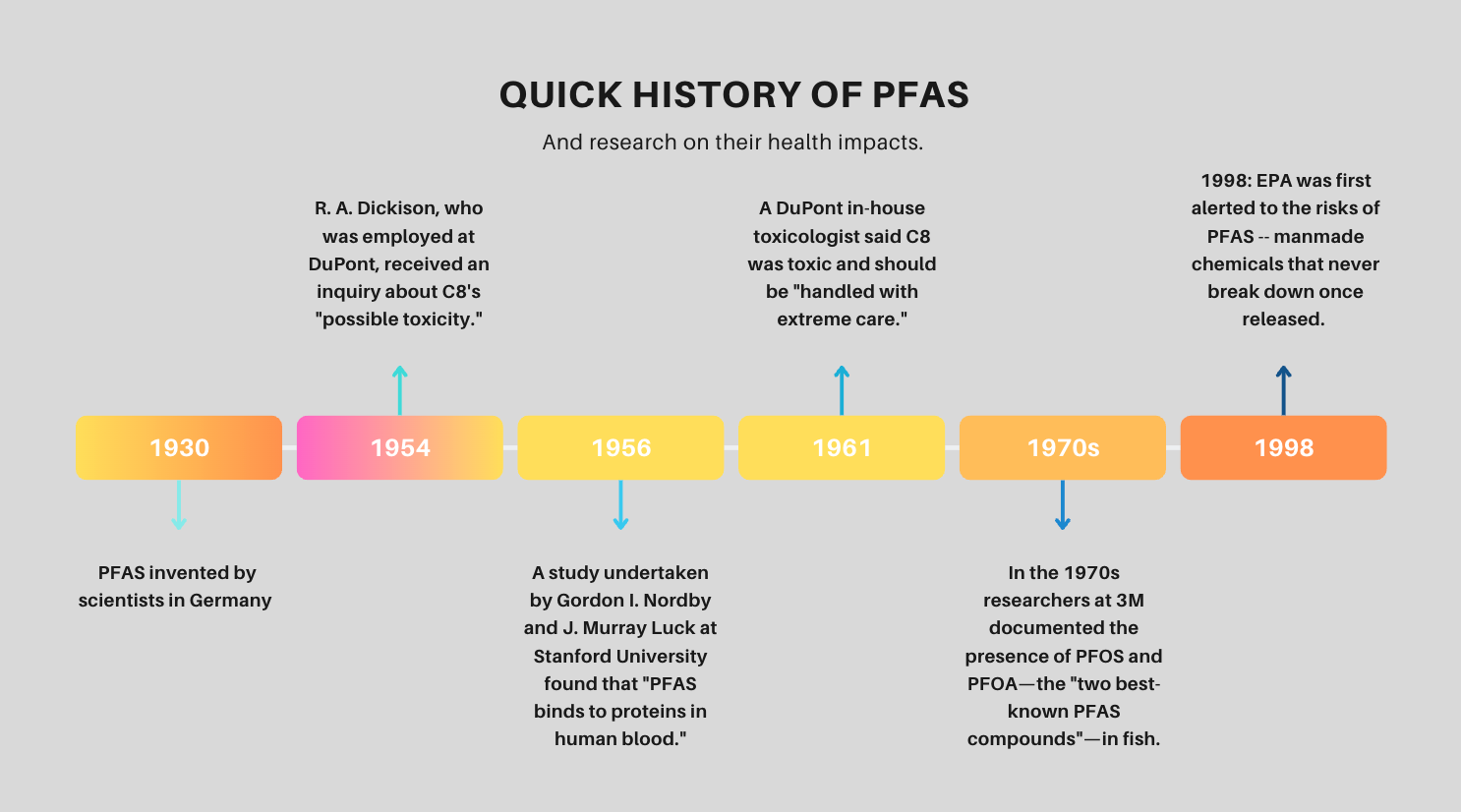

The commercialisation of PFAS can be traced back to the late 1950s and two major companies: DuPont and 3M. If you’ve watched the movie Dark Waters, you’ll be familiar with the former. Both companies were early adopters who began manufacturing, developing, and selling these chemicals for various applications.

Owing to both their long life and ubiquitous use, nearly a century later, these chemicals are still found in a breathtaking array of products – from rain jackets and non-stick cookware to electrical devices, smartwatches, and food packaging. And in terms of pollution, they have spread across substantially every surface on earth, been detected on top of high mountains and in waterways worldwide, including the deep ocean.

However, their widespread use has far exceeded necessity, with many applications persisting despite decades of documented links to negative health impacts, including low fertility, cancer, thyroid and liver issues.

“Every PFAS molecule that has been produced since the late 1930s is still out there,” says Stefan Posner, an independent Swedish polymer and textile chemist who formerly worked with the Research Institutes of Sweden, has spent decades researching PFAS and consulting with authorities in the European Union on regulations. “Unlike other organic compounds that break down into carbon dioxide and water, PFAS degrade into perfluorinated acids that persist indefinitely.”

What this means is that these chemicals never truly disappear – they simply migrate, accumulating in the environment and our bodies, which makes them so harmful.

PFAS in the cycling industry

Most discussions around PFAS in cycling focus on waterproof garments, but these chemicals are woven into far more of the industry than many realise. In fact, there are few places in the world where PFAS don’t exist. PFAS are found in applications from bearing greases to frame coatings to zippers in bikepacking bags to the treatments on cycling shoes. Almost anything that has stain-resistant, waterproof, heat-resistant, or very durable properties involves PFAS in some way.

“It’s in so many unseen places, which makes eliminating it entirely very complex,” says Josh Poertner, founder of accessory and maintenance brand Silca, which makes chain lubes and packs, to name categories where PFAS can be common. And for that reason, it’s good to pay attention to what the brand you consider buying from does.

Did we do a good job with this story?