Bauke Mollema is one classy bike racer: a breakaway whisperer, Il Lombardia champion and a two-time Tour de France stage winner. But the race he contends for with absurd consistency is the Clásica de San Sebástian. He has had ten consecutive top-ten finishes at the August one-day WorldTour event, winning in 2016. The Dutch veteran was gunning for more glory in 2022 until a surprising intervention.

Part of a five-strong chasing group behind eventual champion Remco Evenepoel in the finale, the experienced Trek-Segafredo rider believes that the TV motorbike helped Ineos Grenadiers pair Pavel Sivakov and Carlos Rodríguez to get away from them on the key descent of the Erlaitz.

“If it’s just in front for ten seconds, ok. We would have closed the gap,” he tells Escape Collective. “Two versus three, not a big issue. The problem was, the motorbike was there for 10 kilometres, just in front of them. We could see them for a long time, 100 metres away.

“That was really one of the strangest situations with TV motorbikes I’ve seen,” he says. “I think it also changed the podium of the race. Sivakov was second and I’m pretty sure that if we’d worked together as five till the last climb, he wouldn’t have been.”

We all love to watch pro road cycling but we probably don’t stop to think as much as we should: how much are the TV motorbikes relaying those images, close to the protagonists, affecting races and their results?

Outcry about their influence in leading races appears periodically in the press – take Michael Matthews’ comment that motorbikes “dragged Matej Mohoric away” at the 2022 Milan-San Remo. Or aero assistance in the spotlight at the 2019 Giro d’Italia (hello, Mr. Mollema again), 2018 Amstel Gold Race and 2017 Tour of Oman.

Mollema is unequivocal. “For me, motorbikes influencing the race is maybe the biggest problem in cycling nowadays,” he says. “In most of the races, it has an influence. Making the peloton go faster, mainly, or even the breakaway. Sometimes they are just in front of you when you attack and give you a small advantage.”

TV motorbikes are permitted to move close to cyclists while filming live images. They habitually sit metres away from a breakaway or a peloton, as well as at its rear, to broadcast footage. (There are no specific UCI regulations stipulating their required distance, although that may be about to change).

The aerodynamic benefits they can offer racing cyclists are due to drag reduction. Gravity and friction—at the tires and drivetrain—play varying roles, but at racing speeds of around 40km/h, a cyclist’s drag is about 90% of the total resistance. Having a motorbike ahead can ease that by dragging the air along behind it. In lay terms, it’s akin to a created tailwind – or driving around with an oversize item in your trunk, leaving it a little open, then setting off again and smelling exhaust gas. The cyclist has to penetrate less air; it’s already moving.

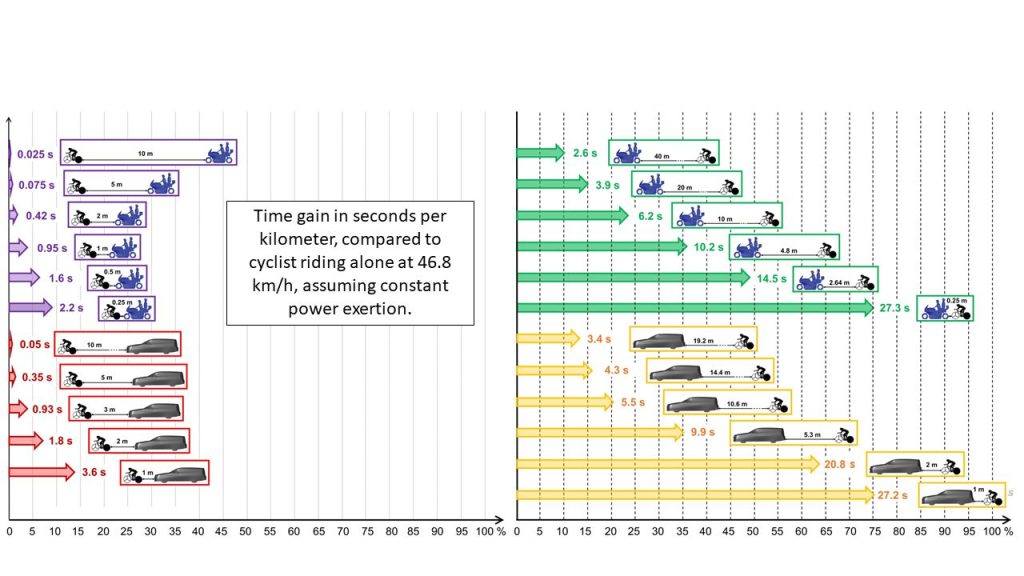

Mollema estimates that the TV motorbike sits approximately 10 metres ahead of the bunch for most of a race. That might seem like plenty of distance, but there’s still a surprisingly large draft effect. In his 2020 study “Aerodynamic benefits for a cyclist drafting behind a motorcycle”, Belgian researcher Bert Blocken analysed the potential drag reduction at that distance to be 23%, resulting in an 8.9% speed increase.

Accordingly, the Trek-Segafredo rider can usually sense when a motorbike is too close to a racer pulling on the front. “You just feel the speed is not natural or when you go over a small bump, you have to go so deep to follow the person in front,” Mollema says.

As for the camera operator and pilot, their remit is to give the best coverage uphill, down dale and on the flat for minutes at a time, staying close to cyclists whose speeds are changing on roads whose direction and gradients can rapidly vary. Fluctuations in proximity are unavoidable.

The current UCI rules do not prevent these benefits from occurring. However, in the governing body’s Guidelines for Vehicle Circulation in the race convoy, camera operators are advised to shoot from three-quarters in front or behind of riders. “They must never interfere with the progress of the race nor allow riders to benefit from their slipstream, especially when the riders’ speed is high,” the document states. It adds that motorcycles should not remain permanently in front of the peloton nor serve as a visual point of reference in a chase.

Well, common sense dictates that these three latter regulations are occasionally broken in every race. Every WorldTour rider has probably gained from this grey area at some point; after all, these are racers who gravitate towards any legal aerodynamic advantage without a second thought.

Time and time again, accelerating riders briefly latch onto the back for a brief draft or catch up on a tight downhill corner before the motorbike engine roars and the vehicle moves away. Or we may see riders, usually riding in a defensive role near the head of the bunch, gesticulating at motorbikes to move away, worried they are aiding a pursuit.

Former rider Simon Gerrans believes that TV motorbikes have a massive influence. “I think that’s a big part of why the average speeds are so high. In professional racing now, there are so many vehicles around the front of the race, whether it’s the motorbikes, the lead cars or whatever it may be,” the Liège-Bastogne-Liège and Milan-San Remo winner says.

The phenomenon well predates even Gerrans’ long career; it used to be a lot worse, as you can see from Marco Pantani’s attack on the Cipressa in the 1999 Milan-San Remo. Before the days of pool photographers sharing images, veteran cycling photographer Graham Watson recalls a flotilla of a dozen mixing on the Poggio in the Nineties, jostling for the shot of the winning attack.

“It looked terrible on TV, was chaotic (and dangerous) on the road, and most definitely affected the outcome of the race,” he writes over e-mail. Watson observed one pre-race briefing at the Italian Monument race where a directeur sportif explicitly told his leader that if he attacked and got in the draft of the motorbikes, he would win.

Of course, the TV motorbike can also serve as a convenient bogeyman at times. “I personally disagree with the suggestion by cyclists that motos are influencing the race. It would look that way if you’re the cyclist chasing a Mohoric or Pantani, but the actual benefit is minimal, more psychological really,” Watson writes.

It’s impossible to measure the direct impact of a motorbike on a race in real-time when so many variables are in flux: wind speed, wind direction, road direction, road width, motorbike speed, cyclist’s speed, gradient, proximity of a nearby vehicle, the position of cyclists in relation to it. (For example, when a TV motorcycle moves to the other side of the road in a bid to avoid interference, riders sometimes move with it.)

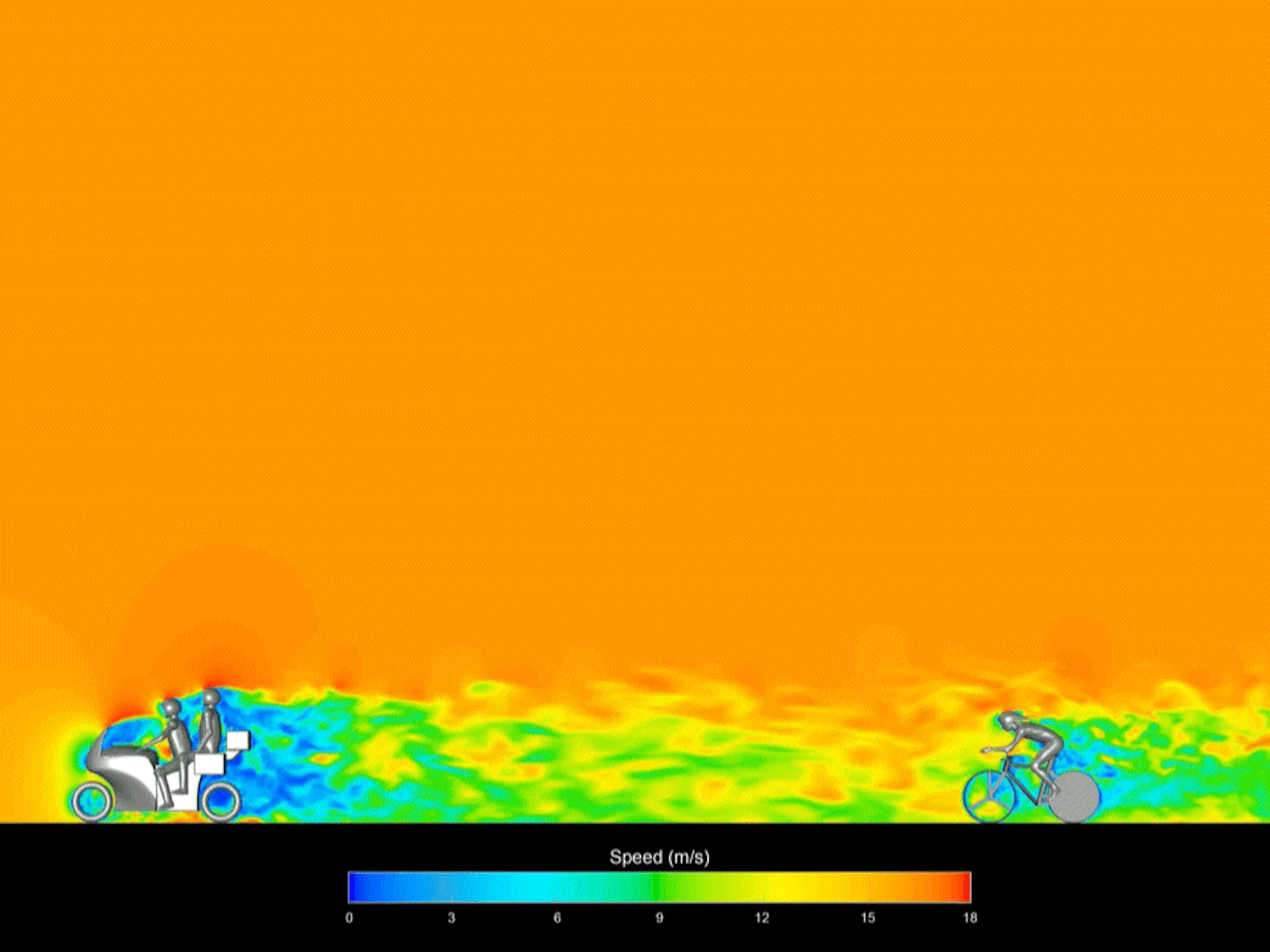

There is cold, hard science to back up these subjective anecdotes. In his 2020 study “Aerodynamic benefits for a cyclist drafting behind a motorcycle”, Belgian researcher Bert Blocken analyses the potential drag reduction to be had, using wind tunnel measurements and numerical simulations with computational fluid dynamics (CFD).

Blocken, an engineering professor at KU Leuven, has two absurdly specific specialties: airflow around buildings and around endurance athletes (he’s a consultant for Jumbo-Visma). He discovered that the benefits of a moto draft can be significant.

At a distance of 4.8 metres between motorbike and cyclist, the drag reduction is 36% and the time gain per kilometre is 9 seconds. At 10 metres, it’s 23% and 5.3 seconds/km. Even at 30 metres away, it’s 12% drag reduction and 2.7 seconds/km. Importantly, in a televised road race, the motorbike usually sits in this window of moderate distance between 10 and 30 metres.

“It happens a lot, in almost every cycle race. It’s not always decisive, but sometimes it is,” Blocken tells Escape Collective. He adds that Milan-San Remo is an event where the influence of motorbikes can be “exploited probably more than in some others. It just lends itself to it,” he says. The rolling last 25 kilometres are ripe for it: from the rapid descent of the Cipressa, where the chasing bunch is habitually on the tail of the motorbike, to the Poggio ascent, where attackers accelerate into a draft, and the corner-strewn first half of its descent, where leaders habitually get extremely close to the camera.

Putting a motorcycle within a few metres of a pro cyclist is like waving a red rag in front of a bull. “We cannot blame the riders. They have to optimise their performance and take any possible benefit they can get,” Blocken says.

The KU Leuven professor’s study concludes that the rules and guidelines need to be adjusted to prevent these undesired aerodynamic benefits. The onus is on the UCI to remove the advantage – and subsequent polemics – with clearer regulations.

Blocken suggests that a minimum of 25 metres distance between motorcycle and cyclist(s) would considerably reduce the aerodynamic benefit. “That is reasonable and I think the TV cameras are sufficiently sophisticated to zoom in and still get good images,” he says. (Theoretically, Blocken would like a minimum distance that changes dependent on wind speed and direction, but that would be practically too complicated to enforce.)

Another alternative is more filming with drones. “I think we’ll slowly but steadily move towards greater use of them,” Blocken says. The recent Gran Camiño, where a drone appeared to flit between filming Tour de France winner Jonas Vingegaard and buzzing him, suggests that’s a work in progress.

It’s unclear why this loophole of undesired frontal gains from motorcycles does not have greater legislation. Helped by Blocken’s newest research, UCI regulations came into effect in January 2023 for time-trials, stipulating that following cars should be a minimum of 25 metres behind in a time trial to get rid of the upstream aerodynamic effect. (At the previous distance of 10 metres, the drag reduction translated to a 3.9 difference over 50km).

“It’s typical UCI; it looks like they admit [the influence] having a team car behind you in a time trial, but they don’t admit having a television motorbike five metres in front of the peloton. That’s a little bit ridiculous, I would say,” Mollema says.

However, it appears that potential changes are in the offing. Blocken says that UCI Head of Road and Innovation Michael Rogers has been in contact with him and is looking into the matter.

“I immediately sensed that he really wanted to do something on it and is keen to make good changes,” Blocken says. “So it took a few years [since the September 2020 report], but better late than never.”

We’ve reached out to the UCI for comment. Depending on their findings, a clearer regulation could come along this season. It may be the end of the road for this decades-long dark art of motorbike drafting in pro cycling.

Andy McGrath is a freelance cycling journalist and the former editor of Rouleur magazine. He’s bad with technology, good with bike race miscellanea from 20 years ago. His Escape Collective columns offer opinion, depth and insight, shedding light on issues affecting pro cyclists and the wider sport. Let him know if you’ve got an interesting lead or a burning topic worthy of discussion on Twitter or at [email protected].

What did you think of this story?