Late last week, on the brutally steep slopes of the legendary Mt. Fuji, Australia’s Nathan Earle (JCL Team Ukyo) rode his way to victory in the Tour of Japan. His stage win, claimed in a mass-start road stage just 11.4 km in length, ensured the 34-year-old would win the eight-stage tour for the second year running. But Earle’s road to victory was anything but easy.

Nine months ago, in September 2022, Earle was hit by a truck driver while out riding in Japan. That crash very nearly took his life, left him with a long list of injuries, and made him question whether he wanted to race a bike again.

It took months of painstaking rehab to get him back to the point where he could ride pain-free, let alone race. The Tour of Japan was just his second race back.

Most Australian cycling fans will be familiar with the basic trajectory of Earle’s career. After years spent racing at the Continental level with the legendary Tasmanian outfit Praties / Genesys Wealth Advisers / Huon Salmon, Earle turned pro in 2014 on a two-year contract with Team Sky.

He raced with the second-tier Drapac squad in 2016, dropped down to the Continental ranks with Japanese team Ukyo for the 2017 season, and then scored enough good results to earn him a recall to the second-tier level in 2018 and 2019, with Israel Cycling Academy. A broken leg in 2019 spelled the end of Earle’s run at Pro Continental (now ProTeam) level, and since 2020 he’s been back with Team Ukyo, plying his trade in the Asian racing scene.

Earle’s career has been marred by a string of significant setbacks. Multiple knee injuries, a collision with a car in 2011 that broke his ankle and wrist, his 2019 leg break, a fractured pelvis while recovering from the leg break (when some people on a bike path pushed a shopping trolley into him), and most recently, his horror crash in September 2022.

Earlier this week, a couple days after his Tour of Japan win, Earle spoke with Escape Collective about his most recent comeback, his Tour of Japan win, his thoughts on how his career has played out, and his philosophy on racing and life more generally.

***

Matt de Neef: For starters, congrats on winning the Tour of Japan again. What are the emotions like after the win, particularly after coming back from yet another significant injury?

Nathan Earle: To win it, and to win it as defending champion it’s pretty special, and for the team as well, obviously, being a Japanese team … It’s not one of the biggest races that we do but it is one of the most important races. And it’s certainly a hard race to win because you’ve got to get everything right for eight days – it’s a long race. So for it all to have worked out and for me to be able to have a great day on Mt. Fuji and the team just ride so well together, it’s just super, super special and a bit of a relief.

We hadn’t won anything until this point as well so there’s a bit of anxiety there on the staff side of things. So everyone’s pretty stoked, which is really nice.

I wasn’t able to find much online at all about the training incident in September last year that left you so badly injured and facing months of rehab. What happened and what injuries did you have?

I was a bit confused about what really even happened and then I just never really put anything on social media. I wasn’t even sure I ever wanted to ride a bike again after that. I love racing and everything, but I wasn’t sure what the right thing to do was. Is it silly after something like this, am I an actual idiot, to get back on a bike and ride again?

So I won this race, Kozagawa Classic, and we went back to the team house and then I just went out with Ben Dyball and Raymond Kreder, my two teammates. We were just riding to the coffee shop, super chilled, and through the same intersection that we’ve been through heaps of times, and we stopped to wait for traffic to pass. And then next thing I knew I woke up in the ambulance.

Apparently, Ben Dyball went first and then I went second and I just got T-boned by a semi-trailer. Raymond was behind me and he didn’t see it either. He almost got hit; he did this awkward stumble because he just clipped in and then somehow didn’t fall into the side of the truck. I just got smoked by it.

I don’t remember anything. I’ve been through that intersection many times and as far as being careful on a bike, I would consider myself one of the most careful riders there is as far as traffic movements, looking behind me, always being aware of what’s going on, not taking any risks.

I really wish I knew what happened or what I did. The truck wasn’t at fault but apparently I wasn’t at fault either. I just don’t know. It was this awkward intersection, we were stopped, there were other cars – it was just mayhem traffic.

So it hit me side-on, on the left. I punctured a lung, broke five ribs or something, split my head open, smashed my helmet to pieces, broke my shoulder, broke my wrist, and broke my arm quite badly. And that was all from the impact of the truck. And I broke a lot of teeth as well – my front teeth – and cracked a lot of other teeth.

And then apparently I got thrown down the road however far. And apparently the truck driver was braking as he hit me – this was a fully loaded semi-trailer – and he stopped within a metre of me on the road.

My helmet was smashed to bits on the side, completely compressed. The helmet straps were torn out of the foam. It 100% did its job. So I’d be dead without a helmet as well. I wouldn’t cross the road without a helmet anyway, but I certainly wouldn’t do it now because it’s not about the speed you’re going sometimes it’s about what else is going to hit you.

Apparently I was unconscious for like five minutes on the ground. And then I woke up and had blood coming out of my head and everything. I was walking around on the side of the road and all the traffic was stopped, obviously. But I don’t remember any of that; the ambulance took like 45 minutes to get there. I thought I woke up in the ambulance but I’d been walking around that whole time waiting for the ambulance.

I couldn’t have surgery straight away because of the swelling and things like that. And then I had a metal plate put in my forearm that wraps around the outside of my elbow. And that’s the only surgery I had to have. They left the shoulder – they said they could do surgery, but it might not make it any better. I’ve got a big lump now but luckily it’s OK. And the wrist just sorted itself out, ribs sorted themselves out. I had to have one of those tubes in my chest to drain fluid from the lung.

I was in hospital for three weeks. And then I wasn’t allowed to fly for another three weeks. So I was here [in Japan] for about six weeks after the accident.

Once I got out of hospital, I went and saw a dentist and got some nice new teeth made up and they put all those in. And then I came home. I was doing rehab in the hospital but then obviously being at home I needed to work a lot on getting my arm straight and sorting my neck out and sorting my headaches and stuff.

There’s a lot of niggly injuries that popped up afterwards that just require constant work that, as any athlete will know, can be a lot worse than the major stuff. You break something, you have surgery, it gets fixed, and that’s kind of it, but it’s been nine months and I’ve still got a sore neck.

I can’t fully straighten my arm and my shoulder’s a little bit shorter too so my overall reach in my left arm is shorter. So I’ve had to adapt to that a little bit. Moving my head on the bike – I’m not as agile as maybe I was before. And then I need to have surgery again to get the metal out of my arm, because it’s still quite sore. I’ve got a bit of constant bruising in there because I think it’s flicking a ligament or something. Hopefully, I can get it a little bit straighter once the metal comes out.

It all sounds a bit shit but all in all, it’s pretty good really. It could be a lot worse. I get to go home and see my family, I get to win a bike race again, get to ride my bike again. There’s lots of positives you can pick out of all of it. Or you could just look at the negatives and feel sorry for yourself. I prefer to take the positive route.

Tell me more about getting home to Australia, getting stuck into the rehab, and getting back to riding?

I pretty much didn’t feel like I could ever ride a bike again. It was that feeling of things never really coming right.

I had three and a half months off the bike. I kept waking with headaches and I just had … not memory loss, but thinking back on that time it’s all a bit dreamlike. I can’t really figure out what week was what.

I tried to ride in November but every time I turned the pedals I just started getting a headache when the blood got flowing. I just gave up and didn’t ride until December on the trainer. And then yeah, a lot of physio and doctor’s appointments and all sorts of things like that. As any cyclist or athlete knows, you’ve just got to get on with it at some point whether it feels good or not. So, in December, I just started riding and it was just all horrible, to be honest.

It’s funny – you get asked the question ‘Oh, it must be a dream to be back on your bike?’ Or ‘It must be so nice to be out in the fresh air again?’ And I’m like, ‘No, not at all. It’s horrible. I’d prefer to just not be riding my bike. It just feels horrible.’

I just wasn’t enjoying it. I was uncomfortable on the bike, it all hurt, I obviously wasn’t fit at all. That was through Christmas and January and even in February I started doing more k’s, but it just didn’t feel good at all. And then Tour of Taiwan came up in March and the team said I didn’t have to do that one, just to focus on still getting better.

And in March, I started doing some k’s and stuff, but I still wasn’t feeling great. And then I went to Tour of Thailand in the beginning of April and that was a bit nerve-wracking just being back on the bike after having an injury and moving in the peloton and just going fast again, basically. But I got through it OK and could help our Japanese teammate, Yuma [Koishi], who got third GC. So that’s nice to be a part of that.

Then I got home, and after so many months, just kind of battling, forcing myself to do the k’s and whatnot, everything just started happening, which was good. I still had a lot of pain in my arm and my neck, I was doing a lot of physio work, still had a big lump, a hematoma thing on my forehead, which hurt every time I’d touch it or bent down to tie my shoelaces or something.

But the form just started picking up and I could recover better, and just felt better. And then coming into May it just all clicked together. I had another three weeks before Tour of Japan so I just trained the house down and came here and then won Tour of Japan nine months after my accident. It’s pretty amazing really, reflecting on it.

What made you keep going with your rehab and trying to return to racing, given it was so difficult and so unenjoyable?

That’s a really good question actually. I don’t know. It’s probably just a combination of everything really. I like racing and I guess my gut feeling was I still wanted to race a bike, my mind was just fighting with that, saying ‘maybe you should actually stop because at some point enough’s gotta be enough.’

But I talked to my wife, and she was happy for me to try again. If I wasn’t trying to ride my bike again, I would still have to get better. And so I thought, ‘I’m contracted to the end of the year, I owe it to the team to at least try and get back while they’re still paying me. And also, I need to get better anyway and if I use the motivation of trying to get back to riding a bike, it might help me get better quickly. And then come 2023, if it’s just not really happening, I can make another decision then.’

And then there’s lots of other things. There’s my children – I come home [to Tasmania], and they’re looking at me. There’s the juniors in the cycling club back home – they’re sort of wondering what I’m doing and if I just sort of mope around and go ‘poor old me, I’m just going to stop now’, it’s not very inspirational to them and it doesn’t really set a good example for my kids: ‘if you have a setback, just give up.’

I just thought, ‘I need to see what will happen if I do try.’ And the worst thing that happens is I try, try, and try, I get better to a point, and then I just decide, ‘no, now I don’t want to do it.’

The team was just so supportive as well. They were giving me the time to get ready, they had belief in me, which really helps as well. Whereas if you have an employer that puts pressure on you, it can put you in the wrong mindset. And that can really affect your recovery and your motivation as well.

So yeah, it’s probably all those things combined, and then here we are.

Tell me about Mt Fuji. It’s an iconic part of the Tour of Japan and Asian cycling more generally. What’s it like to race a stage race that’s 11 kilometres long and just straight up a beast of a mountain like that?

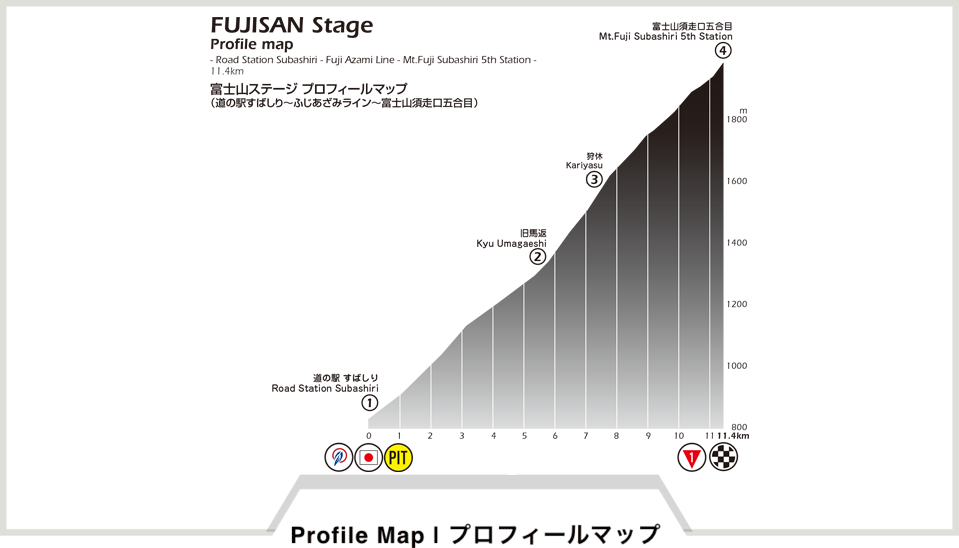

Yeah, it’s pretty special. On paper, when you’re looking at the Tour you think, ‘What? An 11.4 km stage? Is this a joke?’ And then you look at the profile and you’re like ‘OK’.

It’s the shortest stage other than the TT at the beginning. A short stage of the Tour that does the most damage and decides the race. It’s pretty intimidating.

Being so short, you don’t have the chance to shake things out on the bike; you have to do a time trial warm-up, quite a serious warm up; make sure you’re all good with everything beforehand, get your nutrition right. When you warm up you eat like you’re about to do a time trial because you can’t really eat on the climb and it’s a while since breakfast by that stage.

When we got stuck into it I felt really good. Ben Dyball [now racing for another Japanese team, Victoire Hiroshima – ed.] started setting the pace and dropped everyone basically. And then I thought ‘I’m already in front of him on GC so I’ll just wait to see what he’s got.’

At the 4 k mark I was feeling quite good, and he hadn’t really attacked. He’d done a few kind of accelerations but it’s hard to know because the corners are 20% so you naturally push more watts around those. But at 4 k to go I thought I’d just give it a crack and did one sort of attack. I wouldn’t call it a full-blown crazy attack, just more of an acceleration just to see any reaction and yeah, that was it. I was away. I just kept riding my heart out to the line pretty much.

It was pretty emotional at the top just knowing that got me the GC. And for the team, that’s what they were striving for all season. And then just the amount of work I put in training-wise and everything from last year, leading up to that point. It was quite a relief, to be honest; a happy relief to get to the top.

All the help that people give you is probably what I was thinking about as well. You’ve got to do the work but there’s just so many people behind the scenes, whether it’s just a message from someone, people checking in, right down to the physio and massage and other specialists that I was seeing, friends and family, and my wife who is putting up with me every day when I’m talking too much about all sorts of crap. So it’s just nice for it to pay off and reward everyone that played a part.

Was there anything you did specifically to prepare for Mt. Fuji?

To be able to win up there was just so so many weeks and weeks and weeks of training, and then all of May watching my diet, and asking my wife what she’s putting in cooking – she does most of the cooking at home. ‘How much oil have you put in that? How much fat does that have in it? Did you use low-fat whatever for this?’ Just completely pissing her off basically.

Cycling’s a funny one. You go out, you can do up to 30-hour weeks, I was doing 16,000 metres of climbing per week, burning massive calories and stuff, but then you have to watch your diet as well to be as light as possible to have the best power-to-weight. It’s not about being as lean as possible, it’s about having the best power-to-weight you can have.

You see some riders push it too far – they get skinnier, but their power drops and their power-to-weight is worse than it was before and they’re kind of miserable. So you’ve got to find a balance and I did a lot of hard work in that regard.

And then it all just came down to 40 minutes on Mt. Fuji but if I didn’t do that work, I wouldn’t have been able to have that result. But as far as riding it was just ‘make sure you don’t get dropped and then you can attack at the end and be first across the line at the top’. So it’s pretty simple.

I guess the final two stages were reasonably straightforward in terms of keeping the jersey?

Stage 7 was more complicated, because we needed to let a breakaway go so the race settled down, but then not a breakaway with any of the GC riders. So there were maybe 10 riders we wanted to watch. That was not too hard, just monitoring what’s happening and looking at numbers, listening on the radio, checking where people are, who’s moving where, and really relying on teammates to control the race for you.

It’s the sort of stage that, if you get it wrong, and a breakaway goes with someone in it you didn’t want there, it’s very difficult to bring back. I think we averaged nearly 45 km/h with 1,500 m of climbing so it’s a super hard day. And in the end, no breakaways really stayed away, but if you do get it wrong, you’ve gotta ride at 50 km/h to catch the break, and you just can’t do that. So luckily, that went really well and it was due to hard work from my team.

And then the Tokyo stage, again, it was about letting a breakaway go, but dead flat. And my team just rode like 100 men basically and kept everything where it needed to be. And then all the sprint teams got in on the action, because we kept the gap quite small. I just needed to keep safe, which sounds easy as well, but it was just mayhem at the end. I ended up sitting at the back for a little bit and then I just had my teammate move me up in the last 2 km just to not get any time gaps.

It’s still really nerve-wracking – you kind of know you’ve got it [the overall win], but you don’t want to say to yourself ‘I’ve got this, piece of piss’ because as soon as you say that, you could probably lose it. So yeah, it was a big relief after stage 8 in Tokyo.

How do you reflect on your career trajectory over the years? Is there a part of you that would love to be back racing at a higher level? Or are you happy right where you are at the moment?

Well, I’ve got no regrets or anything. I think it’s a bit disappointing that it took me so long to turn professional. Just with so many injuries, I think it took seven or eight years to turn pro since I started riding full time, from 2007. I probably had a combined couple of years off with all sorts of different injuries and operations.

But it was Andrew Christie-Johnston [manager of the Praties team – ed.] that got me through that whole time basically. There were points there too where I just said, ‘I’m gonna walk away from cycling and if I get better, I’ll come back and have a crack’ and he just said ‘No, keep the team bike, you’re going to be back, you’ll win stuff, you’ll turn pro, just keep at it.’ So that took a while.

I’m so grateful to have been able to race in the WorldTour on a WorldTour team. And Drapac and Israel Cycling Academy were Pro Conti but were doing similar races. I think doing all of that has made me the rider I am today, obviously. At some points there, yeah, I wished I could have stayed in the WorldTour or at least in Europe but things just turn out a bit funny sometimes.

At Israel, I broke my femur and then they pretty much just wrote me off and I had a great end of season 2019, but contracts were signed, the team was merging with Katusha, and I was just kind of left by the wayside. Things like that happen and it’s disappointing, but you’ve just got to keep adapting and take what you can get sometimes.

People say ‘I’m too good to ride for that small team. I’m not going there.’ And it’s like, ‘If you can’t find another team, then you’re not too good for that small team, because no one else is signing you.’ You can’t just decide you’re going to rack it because you can’t stay Pro Conti or above; sometimes you’ve gotta go backwards to go forwards.

I rode with Team Ukyo in 2017 and I had a fantastic year at TDU, Nationals, Herald Sun Tour, and then some other results like second GC at Tour of Japan and stuff like that, and then that got me back to Israel. So I got another couple of years there.

I wouldn’t say it’s a regret, and it doesn’t keep me up at night at all because I know everything’s circumstantial, but I’ve never done a Grand Tour. And in 2014, I was supposed to do the Giro but then Team Sky was sponsored by 21st Century Fox so we went to Tour of California and they sent me there to help Bradley Wiggins win Tour of California, which he did. And that was a more important goal, really, at that time for the team, but it meant I missed out on doing the Giro.

And later in 2014 I was supposed to do the Vuelta too. That was the year Chris Froome crashed out of the Tour, so I was supposed to go to the Vuelta but then he wanted the A-team at the Vuelta so I got flicked out of that team. It was supposed to be a younger team, try for breakaways, experience, all that sort of stuff.

And then 2018 I was supposed to do the Giro and then Ben Hermans said he wasn’t really up for a top-10 GC battle. I was supposed to be a support person for him so they got rid of me and put another Israeli in. And then in 2019 they finally said ‘OK, you’re going to the Giro, you’re in the team’ and then I broke my leg in [GP] Miguel Indurain [in April, the month before the Giro – ed.] and had three months off the bike.

On this team now, honestly, I’m happy and I’m content. It’s like a family this team; they look after us. They’re striving to get bigger – we’re going to go to Europe this year – and the salary is quite good. I’ve been paid less on a Pro Conti team before.

And then at home I’m married, I’ve got three kids. We can’t move to Europe. Even when we didn’t have kids, my wife didn’t come and live in Europe; she wanted to work her job. She worked just as hard or harder than I did going to university and doing other crappy jobs until she could get the job she wanted. So why should she leave her job so I can do mine? And she has job security, I don’t, as we know, with injuries. It’s a very fickle sport; you’re hot, and then you’re not. And you might get told one thing, and then at contract time, nothing happens.

Now that we’ve got children, this team I’m on now, they respect my family situation at home, they know I train well at home. They don’t really monitor me too much with the training; they just trust that if they tell me a race is for me to win, that I’ll turn up in winning condition. And it’s short trips, a lot of the time, and it just strikes a really good balance of work and family and being able to live in Australia, really, but still see parts of the world.

Being on this team with my current situation, it really is enjoyable. There’s pressure to perform, but it’s enjoyable. And because it’s enjoyable, you can handle that pressure and you can perform and you can put in the hard effort when it’s required.

So yeah, I am content and if my career does end on this team, hopefully after another couple of years, I would be happy with that without any regrets.

What else would you like to achieve in your career? Are there other races in Asia or beyond that you would like to tick off before you call it quits?

There’s Tour of Okinawa, a one-day race in Okinawa – that would be cool to win. I’d like to podium in Japan Cup, which was a goal last year but obviously I couldn’t do that. I’d like to podium in Europe, in something. I’ve got a podium in Volta a Portugal but it’d be nice to win or at least podium in some sort of a race with WorldTour teams in it.

This year, we’re going to do Ordizia Classic in Spain [a UCI 1.1 event in late July – ed.]; to run top three there would be something. But at the same time … I wouldn’t say I don’t have goals, but it’s not the be all and end all. I just want to do well in whatever racing we’re lining up in. And if it’s not for me, then I just want to help another teammate do well, and just really enjoy what might be the final years of my career.

I’m really happy, and I think that’s the main thing and that reflects well at home to my children as well. I’m pushing myself, I’m motivated, but I’m happy and not bitter to be around. Sometimes you can get into a bit of a hole if you’re not happy in the team, and that can rub off on your girlfriend, your wife, your family, your kids. And you sort of don’t realise and six months later you think back and you’re like ‘I’m not really happy and maybe I’m not really the person I’d like to be.’ I see it happen all the time and I’ve gone through phases like that.

I’m feeling like, now, I am the person I kind of hoped I’d be – happy and positive to be around and a good role model for my children. I think I can’t really ask for much more than that.

Did we do a good job with this story?