Revel introduced the first-generation Ranger three years ago, right around when the whole “downcountry” craze started kicking in. Wait, down-what? It’s a term coined by Pinkbike’s Mike Levy back in 2018 to describe a short-travel full-suspension mountain bike with the heart and soul of a bigger machine. To that end, the Ranger fit the bill perfectly with its scant 115 mm of rear travel and 120 mm up front, packaged in a relatively light-but-tough carbon fiber frame with a fit and handling that neatly split the difference between a twitchy XC racer and a longer-travel trail bike.

Revel has tweaked the Ranger formula for 2023, carrying over the same front triangle and Canfield Balance Formula short-dual-link suspension design, but with an all-new rear end that’s supposedly 20% stiffer than the original while also being more durable and easier to work on thanks to new links, bigger cartridge bearings, and updated pivot hardware. As a nice bonus, it also gets a SRAM Universal Derailleur Hanger for compatibility with the latest Transmission stuff.

Good stuff: Absolutely gorgeous, excellent handling, highly capable suspension, very good pedaling performance.

Bad stuff: Kinda heavy, firm-feeling suspension lacks liveliness, thermoplastic wheel upgrade is a hard sell.

Putting the pieces together

I’ll get to other frame details like geometry and features in a bit, but what truly defines the Ranger is its CBF suspension design. At first glance, it’s not all that different from other short-dual-link designs like DW-Link, VPP, and Maestro in that there are two short links connecting the front and rear triangles together. Mountain bike suspension is all about nuance, though, and aside from that basic trait, there’s actually not a whole lot in common here otherwise.

While it’s easy to identify the axle path and center of rotation on a single-pivot bike, things get a bit more complicated when there are more pivots connecting everything together. However, the upside for designers is you suddenly get a lot more freedom to get things exactly how you want them.

For the Ranger, that means two short co-rotating links anchored at the base of the seat tube, and a shock driven up top by a short yoke extension. Revel says this network of pivots “focuses the center of curvature in a very finite area on the chainline/top of the chainring.” In other words, the idea is to minimize the effect of chain tension on the suspension movement, sort of like how it’s harder to open or close a door if you grab it at the hinged side instead of at the doorknob. And while you can also achieve that by using a lighter-and-simpler single pivot (which is how most modern XC race bikes like the Cervelo ZFS-5 or Pinarello Dogma XC do it), the multi-link setup allows engineers to more carefully fine-tune other aspects separately, like anti-squat (how much the rear suspension compresses when your weight shifts rearward during acceleration) and anti-rise (how much the rear suspension extends under braking).

“All major kinematic designs commonly used today are more complicated than single-pivot designs and for a good reason: single-pivot designs lead to a large number of compromises in order to achieve desired numbers for a select amount of kinematic metrics,” explained Revel founder Adam Miller. “This is why you see many brands running four-bar designs, Horst Link designs, multilink designs, etc. Single-pivot kinematic designs can place the instant center on top of the chainring to emulate CBF from a drive forces standpoint. However, our center of curvature is not a static location like a single pivot would be and is part of what gives Revel Bikes their unique and efficient feel under pedaling load.

“Using CBF over a single-pivot design enables us to tune where we place the instant center and independently tune anti-squat characteristics,” Miller continued. “With CBF, we are able to meet our pedaling characteristics while also being able to achieve the anti-rise values we want. Finally, by using our co-rotating link design, we are able to better tune our axle path for a given model, something that is pretty rigid/non-tunable with a single-pivot design.”

Aside from the aforementioned updates, the rest of the Ranger frame is pretty straightforward. The front and rear triangles are both made of molded carbon fiber, as are both of the updated upper and lower suspension links. And the yoke that connects the rear end of the shock to the upper link? That's carbon, too. The updated collet-style aluminum pivot hardware should be less prone to creaking and/or loosening than before, while titanium is used for the shock mounting hardware.

As before, there’s officially enough open real estate between the stays for a 29x2.6”-wide tire, although now with a few extra millimeters of wiggle room before mud and debris start eating into that pretty paint job.

Revel has opted for a fully integrated headset with drop-in bearings, which makes for a cleaner and lighter setup, but removes the ability to switch out the cups in case you want to tweak the handling. Down below is a conventional English-threaded bottom bracket shell, while the seat tube has a nice, long straight section to run a longer-travel 31.6 mm-diameter dropper seatpost.

As for mounts, there’s room on most sizes for two water bottles – one inside the main triangle, and one on the underside of the down tube – while accessory mounts further up on the down tube provide a convenient place for a repair kit. There’s generous armoring, too, including molded guards on the underside of the down tube and around much of the driveside chain stay, plus a plastic shield to keep pebbles from getting jammed between the seat tube and lower suspension link.

Cable routing is internal through the front and rear triangle, but thankfully not through the upper headset bearing. Further easing service and maintenance are the in-molded guide tubes; just slide the brake hose or housing in at one end, and it magically pops out where it’s supposed to at the other end. Bravo.

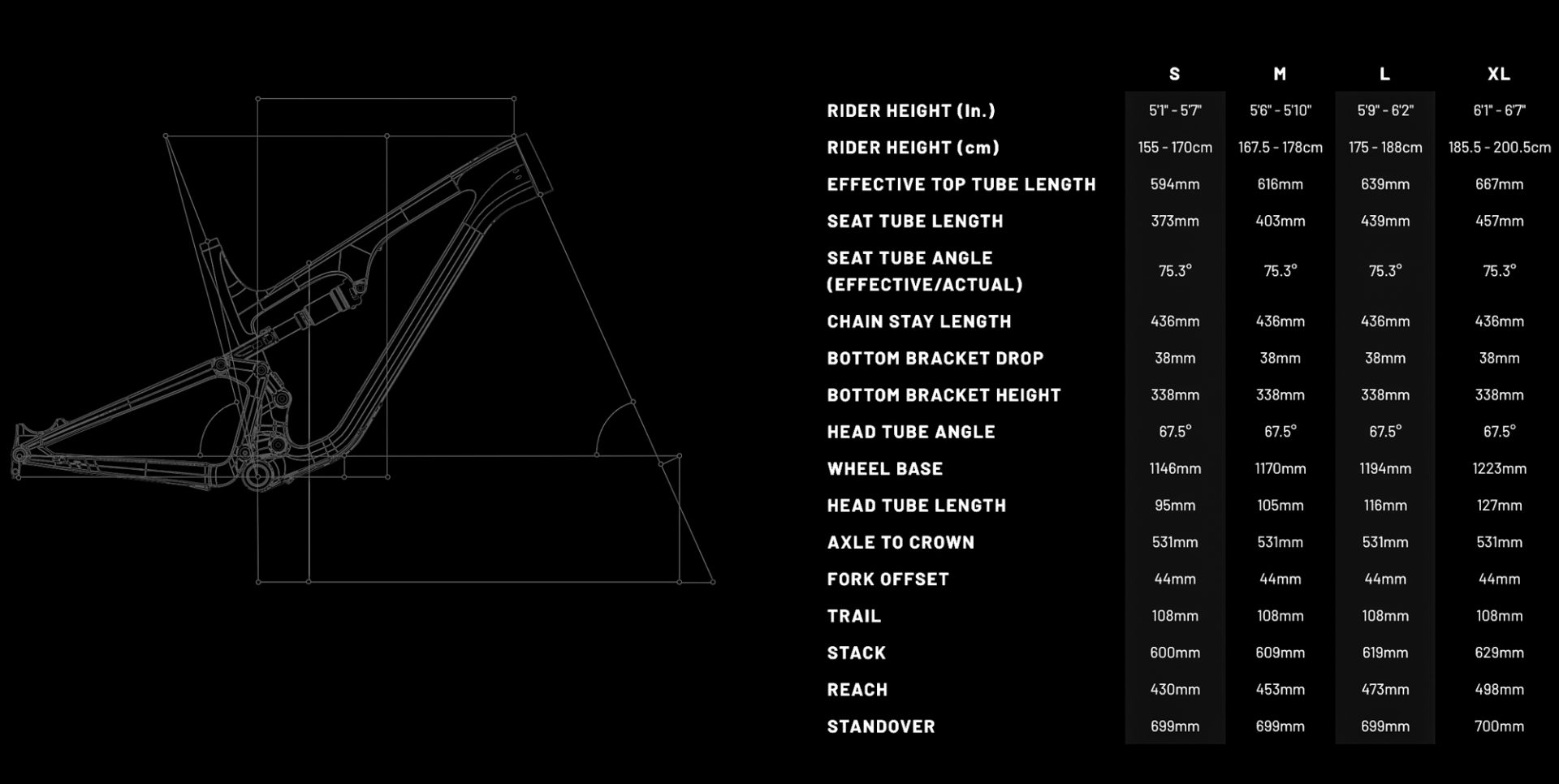

In terms of frame geometry, Revel deftly shoots the gap between XC race bikes and trail bikes. Reach dimensions are fairly long – but not overly so – and they’re matched with 67.5° head tube angles and stubby 40 mm-long stems across the board to provide a blend of lower-speed agility with stability on steep descents and at higher speeds. The shared 436 mm chainstay length is on the shorter side, while the effective seat tube angle is a steep-but-not-too-steep 75.3° for each of the four sizes. Bottom bracket height is pegged at 338 mm – all pretty normal stuff.

Claimed weight for a medium frame is 2,470 grams (5.45 lb) with paint, but without the rear shock.

Revel offers complete builds starting at US$5,999 / AU$9,720 / £5,504 / €6,227 with a SRAM GX Eagle mechanical drivetrain and Industry Nine aluminum wheels, and topping out at US$11,499 / AU$18,398 / £10,549 / €12,030 with a SRAM XX SL Eagle Transmission wireless electronic setup and Revel’s own thermoplastic carbon fiber wheels. For build kits that don't already include Revel's own thermoplastic carbon fiber wheels, you can upgrade for US$800-1,200, depending on which hubs you choose. Bare frames (with rear shocks) are also offered for US$3,599 / AU$5,849 / £3,499 / €3,767.

My particular test bike outfitted with a SRAM XO1 Eagle Transmission groupset, SRAM Level Stealth disc brakes, RockShox SID Ultimate front and rear suspension, a RaceFace cockpit, and Crankbrothers Highland 7 dropper came in at a highly respectable 12.29 kg (27.09 lb) for a medium size without pedals or accessories, but with the optional Revel RW30 thermoplastic carbon fiber wheelset upgrade. Retail cost for all of that is US$9,199 / AU$15,775 / £8,118 / €10,149.

Riding the Ranger

Grading mountain bikes is always an exercise in subjectivity, but when it comes to cross-country bikes, ultimately the most reliable metric is how fast they let you go on the intended terrain. In that sense, the Revel Ranger is an unquestionably fast bike, and true to its “downcountry” status, also more capable than more narrowly focused race machines.

I know this sort of thing is cliché at this point, but I set a number of Strava PRs while riding the Ranger on several of my regular trails – and that was without me even specifically trying to do so. But while it gets the job done with ruthless efficiency, there’s not a whole lot of joy in the process. Almost every time I set one of those PRs, I thought I was going slower than usual.

I’ve ridden a lot of different suspension designs over the years, but as this was my first time riding a CBF-equipped machine, I wasn’t entirely sure what to expect. Generally speaking, I was mostly satisfied with it. After a bit of trial-and-error, I eventually settled on 25% sag front and rear – more than that left the rear end bobbing all over the place and the front feeling wallowy, while less yielded a ride quality that was firmer than I preferred.

At that setting, the Ranger feels mostly like Revel claims it does. There’s still some bob under normal pedaling conditions (as in, seated pedaling at endurance/threshold pace), but it’s not too bad, and mostly only noticeable if you’re watching the shock for movement. It’s admirably resistant to movement when out of the saddle, though, and I rarely felt the need to reach for the lockout lever on the shock except when on smooth pavement. Overall, pedaling efficiency is very good, if not quite on the same level as some others such as dw-link.

Things get more interesting when looking at bump performance.

Although it always feels settled and composed, I can’t say the Ranger’s suspension comes across as particularly supple. A lot of trail feedback comes up through the back end, even on smaller stuff. But as always, what you feel and how a bike actually performs on the trail doesn’t always correspond, and in fairness, the Ranger does a good job of keeping the rear wheel planted to the ground (which is ultimately what matters most). Cornering traction is also very good even when it’s bumpy, and climbing traction on techy pitches is great – just keep the rear wheel weighted and grind away, letting the suspension do the work for you (even if it doesn’t always feel like it is).

Even though it doesn’t always feel like it, big-bump performance is better than expected, with even moderate-sized drops – say, one or two wheel heights – using every bit of the travel, but without a super harsh bottom-out. We’re still only talking about 115 mm of rear travel here so things can go pear-shaped pretty quickly if you push the Ranger too far out of its comfort zone. But generally speaking, it’s impressively competent on a lot of terrain that something with this little travel arguably has no business being on.

The front and rear ends are admirably balanced, with both delivering a similarly firm-yet-supportive ride quality that worked better when really attacking the trail than just tootling along – the harder you hit stuff, the better. However, it’s debatable if that’s a good thing. I enlisted the help of an old friend in testing this – himself a super-skilled trail rider as well as a former tech editor – and we both came to the same conclusion regarding the Ranger’s suspension. It’s very effective in terms of covering ground quickly, but it’d benefit from more suppleness and sensitivity.

The rear end is also a little lacking in pop and liveliness. Whereas some other bikes feel like they just want to play all the time, boosting off of every little rock and root you can launch off of, the Ranger instead prefers to dutifully go about its business of covering ground quickly. That’s not inherently bad, but it’s something to keep in mind when deciding if the Ranger fits your riding style.

My co-tester and I were both more impressed with the Ranger’s handling and chassis stiffness, though.

As I mentioned earlier, the Ranger doesn’t push the envelope in terms of geometry progression; key figures like stack, reach, head tube angle, and bottom bracket drop are all very modern without being at all polarizing. Then again, Revel doesn’t need to stray outside the box here because it works really well.

The somewhat long/low/slack figures make for a setup that relishes higher speeds and steeper descents, lending heaps of confidence in dicey situations and feeling more settled and composed than more racing-focused XC bikes. It’s occasionally a little tricky to snake through extra-tight switchbacks, but it’s a small price to pay for the stability and in no way feels like a sled where you’re just hanging on and relying on the bike to do everything for you. There’s some eagerness in the handling, but still a lot of forgiveness if you get something wrong.

Together with the superb chassis stiffness – which also contributes to reliably precise handling – the general impression is that the Ranger can handle a lot more than its suspension numbers would otherwise suggest.

One last note regarding the frame geometry: It’s disappointing that Revel only offers the Ranger in four sizes (five is more common), but it’s even more of a bummer that so many of the critical figures are shared across the range. While those sizes are intended to accommodate riders from 1.55-2.01 m (5’ 1”-6’ 7”) in height, every one of those riders will get the same head tube angle, seat tube angle, and chainstay length. Even the standover clearance is the same across the board.

It’s nice to see Revel has updated the Ranger with that new rear end, but it seems an update to the front end – along with more size-specific geometry – should go with it sooner than later.

I’d like to see some refinement to the bottle placement, too. While it’s great you can fit a large-sized bottle and a tool kit inside the main triangle, the placement of the rear shock (and especially the location of the inflation valve) almost requires a side-entry cage. My guess is the rear shock is where it needs to be for the desired kinematics.

Build kit report

Aside from the comments about the suspension components I’ve already covered, Revel has done a pretty solid job outfitting the Ranger.

It seems every mountain bike brands send for review these is outfitted with some version of SRAM’s new Transmission wireless electronic drivetrain, which has provided a convenient opportunity to try all three variants. My Revel Ranger tester arrived with the middle-child XO Transmission version, and as I somewhat expected, it performs exactly the same as the higher-end XX SL and somewhat more affordable GX version.

Just as my colleague Dave Rome noted in his assessment of XX SL Eagle Transmission, shift performance from sprocket to sprocket on the XO stuff is nothing short of incredible. Whether in a full sprint or cranking out maximum watts on a steep climb, the system just doesn’t care; just push the button and the chain goes where it’s supposed to go. It barely even makes much of an audible objection in the process, either. Those single shifts don’t happen super quickly, but the whole setup runs very quietly, and if SRAM’s other recent mountain bike drivetrains are anything to go by, long-term durability should be fantastic.

However, while single shifts are truly awe-inspiring, multiple shifts are painfully slow – so much so that I regularly found myself over- or undershooting my target because there was such a huge lag between how quickly I was pushing the buttons and how long it took for the rear derailleur to catch up. This happened even after weeks of acclimating to Transmission’s quirks. And although single shifts were utterly unflappable, multiple shifts weren’t always as reliable or smooth, particularly under load. Even the ergonomics of the shifter buttons leaves a lot to be desired, and regardless of where they’re placed, they require an annoying amount of effort to push.

The matching SRAM Level Stealth hydraulic disc brakes were curiously underwhelming. Despite the four-piston calipers and upsized 180 mm-diameter front rotor, they were lacking in both initial bite and overall power. However, this seemed to be more of a setup or maintenance issue than anything inherent to the design. I have a set of nearly identical brakes on another bike that I know were bedded-in properly, and they’re performing much more like I expected.

The upgraded Revel wheels are intriguing, built with CSS Composites-built thermoplastic carbon fiber rims instead of the thermoset construction more typically used. The ride quality is subtly muted and a more heavily damped than usual, and there’s a distinctly “quiet” feel to them in general (just as I noted on my review of the Forge+Bond 25 GR gravel wheels in June).

However, that distinction is more nuanced here given the much bigger tires and dual suspension, to the point where I’m not sure it’s worth the hefty upgrade charge from the stock Industry Nine Trail S 1/1 aluminum wheelset. The Revel wheels aren’t any lighter, either (in fact, they’re 100 g heavier), and only offer 2 mm of additional internal width. Revel does have a very generous crash replacement policy whereas Industry Nine only offers a two-year against defects for that model, but unless you’re particularly hard on rims and expect to make use of Revel’s program, I’d probably save the cash and stick with the stock wheels.

As for the Maxxis Rekon rear and Dissector front tires, I’m not it’s even worth discussing those given how region- and conditions-specific nature of the topic. Both have a good reputation for reasonable casing durability unless you’re regularly dealing with a lot of especially sharp rocks, and while neither is blisteringly fast in terms of rolling resistance, they offer a good balance of speed and grip, particularly through uncertain corners. In short, neither may be the absolute best option for wherever you are, but they’re safe choices that should work fine for most.

The finishing kit is all solid stuff that should elicit few complaints.

The WTB Volt saddle isn’t the lightest, but it’s very generously padded and proved comfy for hours on end (at least for me). Crankbrothers has thankfully come a long way since its earliest dropper seatposts, too, as the 150 mm-travel Highline 7 model was smooth, quick, and just utterly trouble-free. Travel varies by frame size, too – all the way up to 200 mm on the XL! – and the ball-and-socket mounting style on the remote has long been one of my favorites for how much adjustability it offers.

I can’t say the Lizard Skins grips were my favorite, though. Their pronounced micro-texture is extremely, well, grippy – particularly if you wear gloves – and despite the single inboard locking collar, security was never an issue. They’re quite hard and small in diameter, though, which left my hands aching after a couple of hours. That sort of form factor is exactly what some people specifically look for, though, so to each their own.

As for the Race Face Next R 35 bar and Turbine R 35 stem, what can I say? They do their job, and with impressively low weights considering their immense stiffness, too. That said, I’m not sure that stiffness is entirely necessary here, or even preferred. Given the more XC nature of the Ranger, I would have liked the more compliant feel typically provided by a 31.8 mm setup.

Head to head

One bike immediately comes to mind when I think about what bike people might cross-shop against the Revel Ranger, and that’s the Specialized Epic Evo – and specifically, the Epic Evo Pro LTD. That bike boasts the same 115 mm of rear and 120 mm of front suspension travel, the same RockShox SID Luxe Ultimate and SID Ultimate suspension components, the same drivetrain and brake components, and a similar “downcountry” vibe.

So how do they compare? Bearing in mind I’m comparing the ride feel of a different Epic Evo build (I didn’t have the Pro LTD on hand), the Specialized feels more like a longer-travel XC race bike, whereas the Ranger is more akin to a short-travel trail bike. At least to me, the Epic Evo feels lighter and livelier in general, and more apt to pop and play as you’re charging through the trail. Despite the less complicated suspension kinematics, I’d argue the Epic Evo also pedals a little better, and certainly is more supple than the Ranger’s CBF setup.

It’s also hard to ignore the Epic Evo’s substantial advantage on the scale, with a claimed frame weight of just 1,757 g for a medium size – a difference of nearly 1 kg considering Revel’s 2,470 g claim doesn’t include the rear shock. And speaking of numbers, the Epic Evo Pro LTD is even a few hundred bucks cheaper, and carbon wheels are included stock.

Seems like an easy choice, no? Not so fast. While these two bikes are more similar than they are different, those differences are still fairly significant.

For one, there’s that general difference in feel. When I say the Ranger comes off as more of a short-travel trail bike, that’s because there’s a sense of burliness that’s particularly obvious when you’re charging through challenging terrain. The frame is heavier, but it’s also a lot stiffer, and the while the Epic Evo feels more nimble and agile (despite the slacker front end), the Ranger still feels more confident when you invariably get in over your head.

It wouldn’t be correct to say either bike is “good” or “bad;" it’s more a matter of making sure the flavor profile fits what you’re craving.

Conclusion

It’s hard not to be pulled into the Revel Ranger’s orbit. It’s a gorgeous machine that does everything right on paper with a fancy suspension design, solid geometry, and good numbers, and it’s offered by an up-and-coming Colorado-based brand with a decidedly cool vibe and niche appeal.

But while it’s a highly capable machine, it’s not without its quirks. That versatility comes at the expense of weight, and yet despite the capability, you’re still limited by the XC racing-focused suspension.

Perhaps all of this sounds perfect to you, and perhaps not; it’s really more a matter of what you’re looking for in a bike of this ilk. Even more so than usual, I’d say a test ride is paramount.

More information can be found at www.revel-bikes.com.

Did we do a good job with this story?