Braden Govoni was not surprised. Felt a little vindicated, even.

Back in late 2017, the co-owner of the Outpost bike shop and market in Richmond, Virginia, started an Instagram account with the sarcastic handle @ThanksShimano “almost as a joke inside the workshop” to detail some of his annoyances about the company’s products and practices. Not long after, Outpost processed a warranty of a broken Shimano road crankarm, and he posted a photo of the cracked unit. Fairly quickly, the account became a public repository of sorts for more complaints about high-end road crankarms from Shimano that suddenly, sometimes catastrophically, failed.

As attention to the problem grew, so did @ThanksShimano’s follower count. “Things started to snowball a little bit,” recalls Govoni. “We were seeing more generations of crankarms (fail). This is a known issue that, in my view, was kind of being ignored (by Shimano).” While Shimano had said little more than it was aware of the reports of breakages and investigating, the pattern was clear to Govoni and others: something about how the crankarms were designed or manufactured was faulty. “We saw second-generation 8000 (Ultegra) and 9100 (Dura-Ace) cranks having the same problem,” he says, noting that although the breakage locations varied, they all had the same failure mode. “Eventually I got sent a picture and posted it and someone commented, ‘That was my crank and I crashed and got hurt.”

Just over a month ago, Shimano and the United States Consumer Product Safety Commission proved Govoni and other critics right and formally issued a North American recall of a huge batch of its 11-speed Dura-Ace and Ultegra Hollowtech II road crankarms. The size and scope of the recall – some 760,000 cranksets sold in the US and Canada – makes it among the largest recalls in bike-industry history. Although the CPSC recall technically only applies to crankarms sold in the United States and Canada, Shimano has issued its own stop-ride-and-inspect guidance in other markets; as many as 2.8 million cranksets worldwide may be affected, according to the company, and further formal recalls in other regions may follow.

And while it’s not a surprise, the recall has set off a scramble: at Shimano, but also at some of its industry partners and dealers, not to mention among the owners of said cranksets. Although Shimano issued detailed inspection instructions, there’s still some confusion on the part of retailers and riders about how the process will work. What’s more, the specifics raise questions about how Shimano is handling the recall, and how (and when) all this will ultimately end.

Where things stand now

Starting with the 11-speed versions first sold in 2012, Dura-Ace and Ultegra crankarms are manufactured in two parts for each arm, which are then bonded together with an epoxy. While the technology is referred to as HollowTech II, that term, confusingly, is also used for other hollow-forged Shimano cranksets that are made with a different manufacturing process; only 11- and 12-speed Dura-Ace and Ultegra cranksets, as well as one previous generation of XTR, use the two-part, bonded manufacturing process.

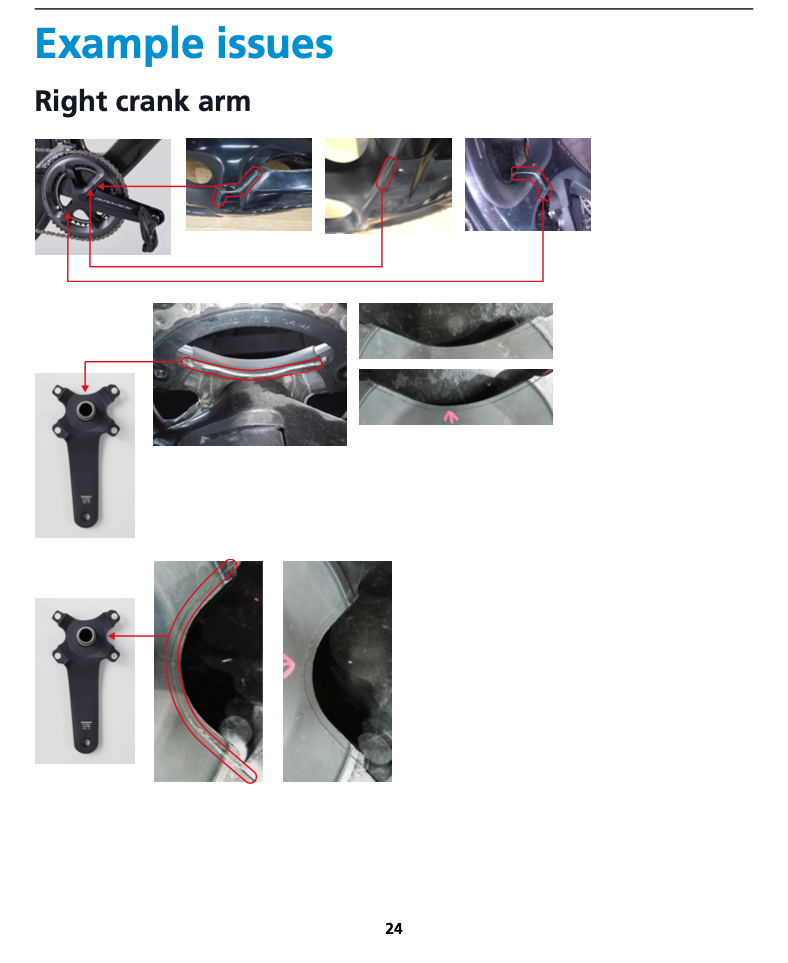

The failure is thought to result from water and salts entering the interior of the crankarm through a void in that bond seam; corrosion eventually causes the crankarm to crack and fail. A substantial amount of the uncertainty around the recall comes from the unusual process Shimano and the CPSC outlined for it. Essentially, while all 11-speed Dura-Ace and Ultegra cranksets manufactured prior to July 2019 are recalled, the recall itself involves a visual inspection process, a pass/fail assessment to check for signs of separation in the bonded seam between the two halves of the crankarm. Only crankarms that fail inspection will be replaced.

That’s quite a bit different than Shimano’s last go-round with a crank recall, when in 1997 it issued a stop-ride order on more than a million lower-end cranksets installed over six years on bikes from dozens of brands. In that recall, customers were directed to contact dealers for free replacements without inspection.

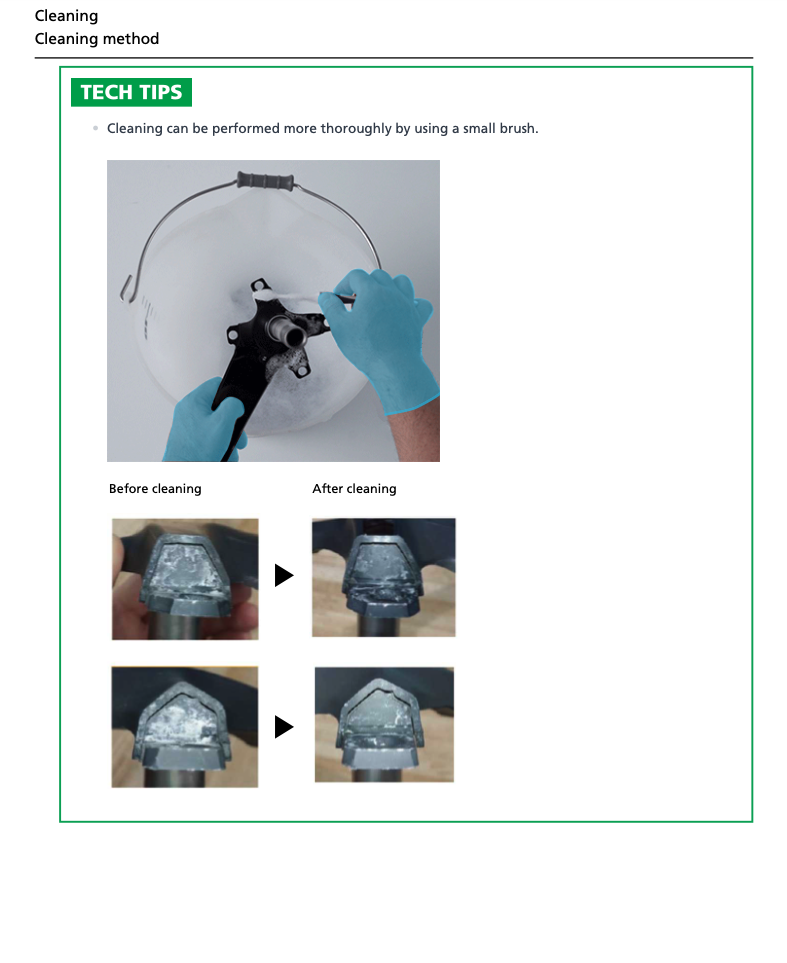

What’s more, the visual inspection process on the current recall will be handled not by Shimano directly, but through its dealer network. Shimano issued a 29-page inspection manual, detailing how its dealers should clean and inspect the crankarms. While that sounds impressive, as much of the manual deals with the cleaning procedure as the inspection process, and most of the included visual examples of failure would be clear even on a filthy crankarm. It’s far less informative on cases that aren’t cut-and-dried.

While Shimano is compensating dealers for the labor (to the tune of a US$75 credit to their account), the multi-step cleaning and inspection process, plus the nine-page web portal form to process a recall, takes a non-trivial amount of employee time (Shimano says it’s confident the reimbursement is set at fair value to its retailers). Some shops will devote a head mechanic to what is a serious, important job; others may deem the whole thing a headache and assign its most junior staffer the thankless task.

Shops aren’t completely sure what to do with customers’ crankarms. Some customers report dealers are telling them only complete cranksets, with chainrings, will be processed. Other retailers process single arms, with or without rings. Still other shops are simply dumping any crankarm with a production code that falls in the recall range into a box and sending it to Shimano as failed, without even cleaning it. The message to Shimano in that case is pretty clear: don’t make this my problem.

Shimano says it will replace affected cranksets with a unit of similar quality, which suggests that Dura-Ace 9000 and 9100 owners will get 9200 crankarms (likely with 11-speed rings). For owners of cranksets with aftermarket power meters from Stages or 4iiii, Shimano will replace the unit and issue a rebate of $300 for single-sided systems and $500 for dual-sided ones, which almost-but-doesn’t-quite cover the cost of a factory-install power meter. Lead times are said to be as little as 3 days for 4iiii, and 2-4 weeks for Stages – but that’s after the initial recall process to replace a crankset, which happens with a Shimano dealer, not Stages or 4iiii.

How long is that? Escape Collective contacted Shimano with a request for comment, and the company agreed to answer questions via e-mail. Those replies are perhaps less revealing than we’d like, but they do answer several pertinent questions not addressed in the company’s public-facing FAQ.

Namely: Shimano is already manufacturing replacement crankarms and, for units in stock, expects the turnaround time to be about 10 days in most cases. Some owners report getting replacements in about a month – a hassle and an annoyance, but nothing on par to the near-year that some Canyon Aeroad owners waited for replacement handlebars in that recall. You don’t need to include chainrings, and Shimano says that for riders who had crank failures prior to the recall that weren’t covered by warranty, to contact their dealer and submit a warranty claim; there’s no single process for that, since each circumstance may be different, but Shimano says customers should follow up with the shop they worked with originally.

Crucially for shop owners, Shimano stated that certified retailers will be able to check a box in the recall claim form that releases them from liability as long as proper training and procedures were followed. The company says its priority right now is to get unsafe cranksets out of the field, and that it does not currently see a deadline after which riders would not be able to submit crankarms for inspection.

That covers at least some of the short-term uncertainty. But the recall has ramifications that will take years to play out.

How we got here

The other thought that went through Braden Govoni’s head when he saw the news of the recall was, “About damn time.”

That certain Hollowtech II crankarms were failing was no surprise to him or, really, anyone in the industry. They’d been failing for years – at least since September 2016, according to one class-action lawsuit around the recall, which claims that Shimano informed the shop that processed the warranty that it was already aware of the problem. Cycling media outlets had reported on crankarm failures as far back as 2020 and yet, until the recall, Shimano’s response to questions was largely that it was aware of reports of failure and was investigating. It also quietly changed some aspects of the crankarm design, like adding a watertight plug to the bottom bracket spindle.

But for almost three years after that initial report, Shimano continued making and selling the crankarms without modification, which is part of the reason the recall covers so many units. And yet, it may be far smaller than the top-line 2.8 million figure, because of how Shimano is structuring the recall to technically only apply to crankarms that show signs of possible failure. (When asked why it wasn’t simply replacing all potentially affected units as in its 1997 recall, Shimano said it’s following the CPSC’s guidelines for this voluntary recall.)

“This is all too common that you see a manufacturer, at least initially, try to get out of it as cheaply as possible,” says John Tangren, a partner at the law firm DiCello Levitt who is leading one of the class-action suits against Shimano. “Even though they announce a recall, the relief will be simply, ‘Let’s take a look at it and see whether we can try to get you to believe there’s actually nothing wrong with it,’ rather than just stepping forward and replacing all the parts the way we believe they should.”

Inspecting the cranks for possible signs of failure is “absolutely not” a satisfactory approach, argues Tangren, “especially since it’s not even clear to us that the replacement cranksets solve the corrosion issues in the first generation (of parts).” For its part, Shimano says that while it can’t share proprietary details of changes it’s made to the design, the company is “confident that these changes have rectified the bonding separation issue.”

The DiCello Levitt lawsuit is expansive, with 16 overlapping claims in California, Florida, and Illinois, and lists Shimano, Trek, and Specialized as defendants. (It’s common practice to name partner companies that use a defective component from a supplier in a finished product. When asked why Trek and Specialized were named but not other companies – Cannondale and Giant, say – that had also spec’d the parts, Tangren said naming partners is an attempt to make sure that other potentially liable parties are included. Other defendants could be pursued later.)

The class-action suit also doesn’t list a specific amount of damages; Tangren says additional work is needed to assess what those figures might be. So it’s impossible to know the full scope of Shimano’s potential liability. This is Tangren’s first bike-industry case, but DiCello Levitt is not two fresh law-school grads chasing ambulances; it’s a large firm with offices in Chicago, New York, Washington D.C., and San Diego that has won nine-figure awards in product liability cases, including US$102 million in a recent auto-defect trial against General Motors. Nor is the DiCello Levitt suit the only class action in the works.

"If claims keep being made and (a company) keep manufacturing products with the same known defects, at some point, the insurance company may say the policy no longer provides coverage for future claims on this defect.”

-Mike Ignatowicz

What’s more, while Shimano almost certainly had product liability insurance coverage, that may only partially indemnify them against losses, says Mike Ignatowicz, an Escape Collective member with 35 years of experience at a leading company in the commercial insurance industry. Ignatowicz spoke from his general insurance-industry knowledge and expertise, but has no specific familiarity with or knowledge of the Shimano recall, or its own and the larger bike industry's insurance practices. (Ignatowicz’s bikes have an Ultegra 10-speed crankset and two SRAM Red cranksets, so he’s not directly affected by the recall.) One question is whether Shimano specifically had insurance on product recalls. “That may be expensive; it’s a specialty policy that may require some things of them in the event of a recall that they don’t want to do,” says Ignatowicz. “A lot of large companies want to maintain their flexibility (in those situations).”

Furthermore, Ignatowicz explains, for bodily injury policies “to be effective, there’s an obligation for Shimano to report (a customer injury) to their insurer. But if claims keep being made and they keep manufacturing products with the same known defects, at some point, the insurance company may say the policy no longer provides coverage for future claims on this defect.” Finally, most policies have coverage limits, although a company Shimano’s size would likely buy excess coverage that applies once those limits are reached. And, adds Ignatowicz, very rarely would those policies cover something like Shimano’s production costs for replacement cranksets.

As the CPSC’s announcement revealed, Shimano had registered more than 4,500 instances of breakage in North America (and, miraculously for a weight-bearing component that sometimes failed catastrophically, only six reports of injury, although the real figure may be higher). That raises a major question: why wait so long to issue a recall? Once Shimano had reasonable suspicion that the failures were at least partly due to a design or manufacturing defect, why not immediately issue a recall? Shimano says it's been investigating potential causes "since we first learned about a possible separation or delamination at the bonded section of certain cranks," but that years-long process and the sheer number of failures in the CPSC announcement suggests it could have acted sooner. There are two possible answers, which interact in complex ways.

An actuarial bet, or something more

The short, unsentimental version is that recalls are expensive: in the Shimano crankarm case, 4,519 failures out of more than 750,000 units in North America amounts to a 0.6% failure rate. The financial cost of making those parties whole, even including settlements in isolated personal injury lawsuits, is almost certainly far less than the cost of administering a massive recall.

But bean-counting alone may not explain it, says Miranda Welbourne Eleazar, an assistant professor at the University of Iowa’s Tippie College of Business. In a 2021 study in the Journal of Business Ethics, Eleazar analyzed almost 850 consumer-product recalls to study the complex behavioral dynamics at companies facing defective product issues.

“You would expect that when products are resulting in injuries and deaths that should spur some kind of reaction, and a company would recall sooner instead of later,” explains Welbourne Eleazar, adding that an established psychological theory, called moral intensity, suggests that the greater the injury, the quicker and more decisively a company would react. “But I was seeing the opposite, and was trying to theorize why.”

The theory she developed to explain it is what she calls immoral entrenchment. Essentially, when a flawed product threatens a company's sales, reputation, even its existence, the organization can often retreat into a kind of defensive self-preservation, marked by insular decision-making and deflection and denial of responsibility.

When I asked Shimano what led the company to finally issue a recall, the indirect answer was largely the same as its pre-recall messaging: that since the first reports of bonding failure, the company had been investigating potential causes: “We identified various external factors as well as severe environmental conditions could be involved, but there was no singular cause."

That partly tracks with what sources like Govoni told me: that while factors like saltwater air or sweat were likely part of the issue, there was no singular use case, age of the part, geographic, or other pattern to the failures they’d seen other than that they all occur somewhere along the bonded seam between the two halves of the crankarm. But that last part highlights what Shimano still doesn't say: all crankarms, of any brand or method of manufacture, see use in those conditions, and yet it’s only these particular Hollowtech II units with the two-part bonded design that are failing in significant numbers. In addition to "external factors," that points to some underlying design or manufacturing issue.

Again, Shimano didn't directly address the question of what finally spurred its recall and why it only issued one now. But Welbourne Eleazar's study found that, paradoxically, the worse the risk of harm to customers, the more companies dig in. When customers were injured, companies in the study's dataset took 31% longer, on average, to issue a recall. If someone died as a result of a defective product, the time to recall increased 86%.

For Welbourne Eleazar, it's an uncontroversial assertion that companies have a moral responsibility to not harm their customers, although she outlines the evidence for that argument in her paper anyway. In that sense, the Shimano recall doesn’t perfectly fit the immoral entrenchment theory, because there were only six injuries reported to the CPSC in those 4,519 failures, and no deaths. But Welbourne Eleazar's research also found more modest correlations between recall delay and the size of the recall and the sales price: the bigger the recall and the more expensive the product, the more entrenched a company was, and this particular recall was of a widely sold, relatively expensive part.

While most of the affected models were included on complete bikes, the retail value of the cranksets alone ranged between $270 and $1,500 for the power meter versions. When I asked Shimano if it had met the moral standard of protecting its customers, the company replied only indirectly, saying, “Shimano takes rider safety seriously and we are always working to enhance production techniques and technology … while maintaining the highest quality and safety.”

Destination unknown

For Tangren, foot-dragging on recalls is “a frequent feature of our cases,” but says what’s driving that behavior isn’t a complex moral dynamic, but instead often boils down to companies “really, just putting profits above safety.” In other words: no, it's just bean-counting. Tangren, of course, is not an impartial observer, and Shimano says that it monitors warranty issues and failure incidences in all its products, making necessary changes to enhance safety.

But whatever the case, the recall will absolutely be a hit to Shimano’s bottom line. If you look only at the hard costs of administering the recall that may be outside the scope of its insurance costs – to manufacture and ship the replacement cranksets and reimburse retailers for labor – Shimano is looking at a major hit, possibly around US$40-$50 million to replace even 10% of affected units worldwide. That’s far from a catastrophic loss for a company with nearly US$4 billion a year in revenue, but it also doesn’t include the costs of defending against the lawsuits and potential payouts in settlements or verdicts, and that its insurance premiums will almost certainly rise.

And, it’s coming at a bad time: the big profits of the pandemic boom are over, and in its latest quarterly earnings report, for a period which pre-dates the recall, sales in Shimano’s bicycles segment dropped almost 25% (in what is sure to be a recurring theme in earnings season, the company blames high inventories.)

As Govoni told me, the impression in the industry of Shimano has long been that the company views bike makers as its customers; the rider is an end user, a customer of Shimano’s customer. That is technically correct, as Shimano doesn’t sell consumer-direct, but that’s still different than how many industry brands perceive their relationship with cyclists. But sources I spoke with said that they do think there’s a chance the recall will even harm Shimano’s massive original-equipment business, which is the heart of the company’s cycling-division earnings.

And the recall may have an effect on riders as well, if only in the broad sense of confidence in the company's products and its responsiveness to problems. When those products cause harm, customers tend to respond most positively to companies that react quickly and decisively. A decade ago, SRAM’s nascent drop-bar hydraulic brake market was almost killed before it got going. Just months after the company released its first Red and Force hydraulic braking systems, SRAM learned during the cyclocross season that a design defect risked causing a seal failure at extremely low temperatures – the kind you might encounter racing bikes in the northern hemisphere in December. Some 25,000 units in North America were affected.

SRAM received 95 reports of failure (for comparison, a 0.3% failure rate), with two injuries, before issuing a recall in December 2013. The remedy: a free replacement system and $200 in cash or voucher for future purchases. At that month’s National Cyclocross Championships in Boulder, Colorado, SRAM’s neutral service tent was packed with mechanics doing brake swaps, and CEO Stan Day was publicly apologetic.

“First of all, the individuals who suffered the most pain in this were consumers who spent their $5,000 on a bike,” he told me in an interview at the race, adding that the episode had also hurt dealers who now had bikes they couldn’t sell. SRAM’s failure reports piled up fast, but Day claimed the problem only became acute the first weekend of December. According to Day, that’s when SRAM received multiple reports of brake levers “going to the handlebar” and losing all hydraulic control in very cold conditions, and knew it had a major problem and had to act fast. “We tripped and we hit our face on the sidewalk and we’ve got to get ourselves back up,” he said then. (SRAM has, we should note, had long-running quality-control issues on some of its mountain bike brakes that have not resulted in recalls and are a continuing source of frustration for riders and dealers.)

The episode did harm SRAM’s OE business for a time but ultimately, SRAM survived mostly unscathed, and acting quickly likely prevented the problem from growing exponentially worse both for hard costs and from a reputational perspective. The gold standard for “How to behave in a recall” remains the 1982 Tylenol episode, when Johnson & Johnson yanked millions of bottles of the painkiller off shelves nationwide after seven people in the Chicago area died as a result of cyanide poisoning. It later emerged that the deaths were the result of intentional outside tampering (the perpetrator was never caught), but J&J reaped years of public goodwill and the episode was widely taught as a case study in business schools as a paragon of swift, decisive action to protect the public. (As with SRAM, J&J’s more-recent record is mixed.)

The irony is that, by its own actions, Shimano may be prolonging the very thing it sought to avoid. Because it’s recalling only visibly affected products, there are millions of cranksets out there that may circulate for years. If and when they break, those failures will continually re-surface the issue.

And owners of the cranksets face two dilemmas: how they’re supposed to trust those parts are safe to ride, and what to do with them if they’ve lost that confidence. When asked what owners of “passed” units should do, Shimano replied with a version of its public FAQ response, saying it encourages retailers to remind customers to maintain their bikes diligently and have them inspected regularly, to listen for changes in the sound and feel of their bike, and pointed to a YouTube video of an inspection process riders can do on their own. That likely comes as small comfort to anyone with a crankset in the recall batch that “looks OK” right now. "Even if your crankarm passes their visual 'inspection,' would you feel comfortable using it? I wouldn't," wrote one person on a ThePaceline.net forum thread on the recall. If you don't want to use it anymore, do you sell it? Give it away? Take it to scrap-metal recycling? Shimano isn't the only entity facing an ethical decision here, but by only replacing affected units, it's created that situation for riders.

One of the questions I had for Shimano was why the recall only covered bonded cranksets produced through July 2019. That was two years before the launch of the redesigned Dura-Ace 9200 12-speed group, and both the modified 11-speed crankarms produced after July 2019 and the new 12-speed crankarms broadly use the same two-piece, bonded manufacturing process as the recalled versions. What – other than the addition of the watertight plug in the BB spindle – was different, and how could Shimano prove to riders' satisfaction that a revised part with the same basic construction process was now safe? While it’s widely suspected that the failure mode was internal corrosion, again, Shimano won’t detail what it’s changed or how riders can be sure those fixes work aside from essentially asking us to trust it.

All of that – the size of the recall; how it’s being implemented; the civil lawsuits and their often-slow pace; and Shimano’s incomplete answers to questions about whether the issue is fixed – suggests that this episode will likely drag on for some time. But there is a set of bigger issues as well, like whether this will affect the company’s reputation and place of prominence in cycling components that it’s had for decades.

A common response to man-made quagmires marked by fallible decision-making is a simple query: “Tell me how this ends.” As long as Shimano continues to be tight-lipped about the failures, and refuses to detail what it’s changed to end the problem, no one outside the company can confidently answer that question. The bigger unknown is whether anyone inside Shimano can either.

Did we do a good job with this story?