Escape and escapism mean something ever-so-slightly different for everyone, albeit around the axle of an abiding assumption: a desire or need to get away, usually from an uncomfortable reality, by way of activity or entertainment.

Assumptions typically form the basis of our understanding, a scaffold perhaps, but occasionally, we get it wrong, the blueprint is upside down or inside out. Challenging our assumptions is to see things differently, and Luke Grenfell-Shaw is on a mission to help us all do just that.

A trail runner, adventurer, documentary producer and charity patron, Luke has been on quite the journey. It began in 2018 when he was diagnosed with incurable cancer after rushing home from Siberia, then very quickly started chemotherapy, and lost his brother – all within five weeks. Eighteen months later, after completing a Master's at Oxford University’s prestigious School of Geography and Environment while continuing his cancer treatment, Luke embarked on a several-thousand-mile tandem ride from Bristol to Beijing. It took rather longer than expected to complete, but against the odds, complete it he did, and since arriving home in 2022, he’s become an accomplished trail runner sponsored by Brooks, received an MBE for services to charity, celebrated his 30th birthday, and last week he premiered his documentary film ‘A Life in Tandem’ that tells his extraordinary story.

This young man has defied the odds and is challenging narratives left, right and centre.

Building a mindset

When Escape Collective spoke to Luke, he was sitting in a cafe in Almaty, Kazakhstan, a place he says feels like a second home amidst the chaos of travel and whose mountains have become his playground. He told me about his family, his childhood, and growing up with a healthy diet of exercise, travel and adventure that would prepare him for what lay ahead.

“I was never sporty in a traditional sense,” Luke began. “All the way through school I was not particularly good at rugby or cricket or any of those sports, but from a young age we went orienteering as a family, that was our classic Sunday morning activity. And our family holidays tended to be pretty active: we cycled the West Country Way when John [older brother] and I were I think far too small to enjoy it, and then ditto cycling down the Rhône when I was about 10. I just remember that being one long boot camp to be honest. I think the furthest we went was 40 miles on one day and it felt like an eternity, and at that point, I did not particularly enjoy it – it just felt a bit of a suffer fest, but I think it paved the way for falling in love with it.”

As his body developed and he matured, Luke began to find his own way into exercise around the age of 14, and running became something he did every day. Within a few years, that progressed into triathlon and duathlon – “my swimming was never so good” – and the competitive bug had bitten by the time he headed to university in the north of England.

“When I look at my athletic journey I see it having started before I was 10, and yet only in the past two or three years do I really feel I'm beginning to train properly. Oftentimes I look back and I think why was I so unaware that the top people at that level have already been training 20-25 hours a week when I still thought it was enough to just do a five mile run. I had no idea really what a training regime looked like. And if someone had given one to me, I'm not sure I'd have done it.

“I always thought if I ran hard enough in the race, I could win. So the only thing that was stopping me from winning was going even harder.”

At no point has Luke focused on one thing or been defined by a single output or purpose. At school, he balanced his active lifestyle with a busy academic workload and extra-curricular activities including practising the bassoon and bagpipes – it seems he rarely, if ever, sits still.

After finishing up his studies in Natural Sciences at Durham University, Luke postponed further education or entry into the world of work with a year spent teaching in Siberia, also an opportunity to discover a new part of the world. With a CELTA English language course under his belt, Luke jetted off to Tyumen, Russia.

“That was my first time getting away from home as an adult and forming my own group of friends in a first proper job, and also I did my first ultramarathon there. That was 50 K in the Ural Mountains and I lost to a Russian guy who had run a 63-minute half marathon back in the day. I killed myself in that race, metaphorically, but comparing myself against the competition, I've never been at that level of speed, but somehow I could hold my own in this longer distance. I thank my parents for that, for those long bike rides and active family holidays. It paved the way for what came later.”

Siberia provided a first taste of true independence for Luke, more so even than the gap year of traveling and volunteering after leaving school in 2013, but everything was about to change. The rug was crumpling, ready to be pulled.

“It actually goes back to the September of the previous year when I was noticing my shoulder aching a bit, but it was intermittent. Sometimes I’d notice it running but I’d just shake it off. But the niggle hadn’t gone by March 2018, so at that point I go to the physio who says it's a winged scapula, so I just had to do lots of band exercises. And when that didn't help, I just went even harder on the exercises.”

The relief afforded by the physio’s plan was short-lived, however, and it’s clear that Luke had been at least a little worried as he recalled taking photos of his back which, when the muscles were relaxed, “looked a bit odd”. Before long, Luke was compelled to seek further advice, finally visiting the nurse attached to the school where he was working after finding a bump in his left armpit.

“So the school nurse had me take my top off and when I showed her she was like ‘oh my god’, and it was only then that I realised: right, this is actually something serious.

I noticed Luke’s demeanour change slightly as he reflected on this life-changing episode, his eyes shifting away from the screen of his laptop as he drifted into a significant past.

“It was strange, I remember it very well. It was early afternoon when I saw the nurse, and at one point she left and brought back the head of the school, a guy called Tom. He took a look at it, my back, and then they sent me off to get a scan done. When I came back into his office he was chatting a bit with my mum, but I was like, ‘my lessons are starting in five minutes, I need to go’, but Tom said ‘don’t worry about that, I've got someone else to do it.’

“That was one of those moments where you’re like ‘what?’ It’s almost…that kind of level of care, it throws you, but you lose control a little bit. So I didn't teach anymore, and the next day I packed all my things, said a hasty goodbye to the other teachers without really being able to tell them why, because I didn't know – all I knew was that the NHS was the place I and my parents wanted to be rather than the Russian healthcare system for what this might well be.

“Within 48 hours I was back in the UK. It was very rapid and I was never to return to Tyumen.”

A world turned upside down

‘What this might well be’ was already taking shape in Luke’s mind. The quick scan had revealed a large aubergine-sized mass under his left shoulder blade, and though staff had been careful to reassure him, Luke wasn’t convinced.

“I got the diagnosis three weeks later,” his tone returned to the simple pace of a now-experienced public speaker. He was told he had a very rare and aggressive sarcoma with the primary tumour under his scapula and 13 cancerous nodules in his lungs. That the primary tumour had metastasised made it stage IV, which meant it was essentially incurable. There were treatment options for Luke, and his cancer was not yet terminal, but he’d been handed a reality he'd carry for the rest of his life.

“Prior to the diagnosis, even on the day of the meeting with the nurse, I remember asking the doctor doing the scan, ‘are these cells cancerous?’ and she said they weren’t, but I didn’t really believe her answer. So it was already in my head.

“Chemo started two weeks after that. It all happened – for me in that position, at least – frustratingly slowly.”

Though that time was punctuated with appointments and scans, little happened in the two intervening weeks besides waiting. In fact, under the compassionate advice of one of Luke’s doctors, the family took a short holiday in Wales, and it was no less active than any other trip the Grenfell-Shaws had taken as a family.

“I remember John and I cycled over from Bristol to Abergavenny together, and he was going easy, but I was pretty much on the rivet the entire ride. John had been building his cycling game up and up and up and was in really amazing shape.”

It was a holiday of bike rides – watching John shoot off after KOMs – peace and quiet, but there was a reality Luke could not escape from. Just a few weeks earlier, he’d been enjoying a life of running and working in an exciting new city, his whole future sprawling ahead of him. But that assumption had evaporated before his eyes as the doctor explained his prognosis.

“My timeline was massively shortened. The diagnosis completely caught me by surprise – not that I had cancer, but that it was stage IV and very rare so ultimately untreatable. I had 13 metastases in my lungs. You can operate on and remove a tumour, but the fact it was in my lungs, you can't really get rid of those, so it was a very bleak outlook. Just the end of the summer was an impossibly far-off concept, and the fact I had an offer to do a Master’s at Oxford, that was just impossible to even think about, even though it was only in three months time, because I had six rounds of chemotherapy before then – if I was lucky enough to get through all six.”

The course of treatment is different for everyone, but for Luke it meant four days in hospital every three weeks, six times over. On each of those three days, he’d receive his dose of “two pretty nasty” chemotherapy drugs and be on a drip for 20 hours a day. He’d then feel pretty sick for about three days after leaving hospital, but then there’d be two weeks in which he’d feel pretty normal, he could run, cycle, see his friends, all things that would help rebuild and keep his strength between – and during – rounds.

“During treatment, I'd walk every single day for an hour when I wasn't on the drip, and my dad brought my turbo into my room. I think it's important to stress that I wasn't doing a session in any way, I was just turning the pedals over, but that's better than nothing. And that's really the mentality of some physical activity – some movement is going to be infinitely better than just sitting on my bed all day.”

But something else happened while Luke was undergoing treatment, a fact of human life that was staggering in its timing. Luke was very close to his brother John, just eighteen months older than him and firmly ensconced in a mathematics PhD at Cambridge University. Shortly after John had joined his family in Wales in advance of Luke’s treatment, another impossibly unfair – or what most of us would consider impossible – twist of fate hit the Grenfell-Shaw unit.

“No one knows quite what happened. John was at Trinity College, Cambridge, and they have this thing called the Hunt, which I don’t think is officially linked to the college, but it's all Trinity members. It's a Hare and Hound sort of game that happens in the Lake District every year – something that had been the highlight of his year for, I think, seven years, and something I was very jealous of – and John was a hare that day. It sounds like he was trying to evade the hounds when he went round quite a steep side of one of the hills … probably 99 times out of 100 he'd have got away with what he was doing, but for whatever reason he slipped, he fell, and he fell in a really bad way, hitting his head after falling some distance and…and he died pretty quickly.

“I found out on the morning of the third day of my first round of chemotherapy. I went in on Tuesday and the final day was the Friday, and dad was with me in the room when he got a call from mum at 3 or 4 a.m…”

Luke has spoken and written quite openly about the sense that he didn’t really grieve his brother, not at the time anyway.

“I think the first important thing to say here is that there's no right or wrong way to grieve. I just want to send that out as a hug of compassion because I think some people feel that they should be feeling something that they're not.

“I didn't grieve for John I think for a couple of reasons: the first and foremost is that I was so focused on my own survival and the fact that I was probably going to be dead so soon meant that I didn't have the bandwidth or capacity. And I didn't have any survivor’s guilt because I was going to die pretty soon too. I think also for me, three weeks before, my own life had been turned upside down, the impossible had just happened to me. And so what happened to John was no longer impossible. In fact, that was kind of normal for the world I was now living in. If I can get diagnosed with stage IV cancer aged 24, then I guess John can fall and he can die, and all sorts of other stuff can happen. The laws of life were suspended. It was totally different for my parents, of course.”

Grief came later, and in particularly profound moments.

“It comes out most powerfully when I feel I know exactly what John would have done or how he would have felt in a particular situation. Calling him to mind with such clarity then accentuates that loss because you can feel the reality but you can see that it's not there, and that's the loss.”

Taking back control

Looking in from the outside, more happened for Luke Grenfell-Shaw and his family in six months than most people go through in years, even decades of life. But Luke made it to the end of the summer, he made to to the end of chemo, and he made it to Oxford where he could begin to reclaim a life that had become – and would remain – precariously balanced.

“I think it’s about not being defined. It's something that I thought about a lot and was very aware of, particularly going through chemotherapy; being a patient is a very passive role and it's very easy to slip into the self-belief that comes with it, that you don't have control over anything, you’re someone who needs to be looked after. And I think that to me is the first step that I took before I went to Oxford: inserting Luke Grenfell-Shaw back into this patient was the exercise.

“It really helped to have another focus too, many other focuses. When I was going through chemotherapy I was still finishing off other bits of work, for instance, I was trying to finish a chapter on the genetics of quinoa that I'd been working on for months, and at Oxford I was involved in the Oxford Development Consultancy and racing duathlon – all those things were really important.”

There was a message for his doctors too. In moving from Bristol to Oxford, his treatment also shifted from Bristol’s teenage and young adult cancer treatment centre to Oxford's Churchill Hospital, and as he began a radiotherapy regimen while studying, Luke would run there from Worcester College – about a nine-mile roundtrip – a hugely important feature of his routine that he considered key to his treatment.

“I think I wanted them to take note in a sense, that I was ready to get in there. I'd never have thought about it at the time, but it's something like how two boxers face off to each other before the fight, you want to be up in their grill a bit. The consultants were brilliant, I should say. The team was brilliant, but I wanted to make it clear I was not going to be your typical patient. It was one of my strategies of coping.”

And all the while, Luke never really believed he’d make it to the end.

“I started Oxford against what I expected, but I still didn't expect to finish. And when I was halfway through my time at Oxford, even after the surgery and radiotherapy, even then, the expectation was always that my cancer would come back. And so my timeline was always three months at a time, it was a waiting game between scans.

But a little over a year after he started, and after juggling a summer of teaching human geography in Kyrgyzstan with writing his dissertation, Luke graduated from one of the world’s best university’s with a distinction in Water Science, Policy and Management.

Eight weeks later, he was setting off on his next big adventure, and fulfilling a dream that was a decade in the making.

Living the dream

“‘Bristol2Beijing’ was something I'd had in my head through my late teen years. Even on the day I was diagnosed, there was this little nugget in my head that thought if I have the chance, that's what I want to do with the rest of my life, the time I have left.”

The plan was in motion in the summer of 2019 after he’d finished treatment, and not just for the ride: Luke would be filming along the way and keeping a detailed diary to facilitate the later writing of a book, while also raising money for the charities Move Against Cancer, Trekstock, Young Lives vs Cancer and Teenage Cancer Trust.

“I, as you know, love traveling and I’ve always been very interested in different cultures. I studied Arabic as part of my undergrad, so I spent time in the Middle East, and quite a bit of time in Russia [he studied Russian at A Level]. I was really interested in the idea of the Silk Roads, and particularly the new Silk Roads or the Chinese Belt and Road initiative, so I thought it would be cool to trace the old and new Silk Roads. All that meant the obvious destination would be China at the far end of Eurasia, so Beijing, the capital, was the obvious choice and had pleasing alliteration with Bristol.”

While there was a very clear desire to experience and bear witness to an ancient and developing conduit of culture and commerce, something not connected to his cancer, there was a symbolic and practical significance in Luke’s choice of a tandem – which he named Chris, his brother’s middle name.

“At the earliest of stages, before I'd even started chemotherapy, there was an understanding that John would have joined me for at least part of it and we'd have cycled together. Then after I'd gone through my treatment, I realised how important my friends were, and how important it was to share experiences, so I knew I didn't want to do this by myself, I wanted to share it. But I'm also not very patient as a person, particularly when it comes to cycling or running. So a tandem's the perfect solution – anyone could join no matter their fitness; I was happy to pedal as hard as I wanted to pedal, and whatever someone on the back could offer is fantastic. It became a very inclusive way of doing this trip.”

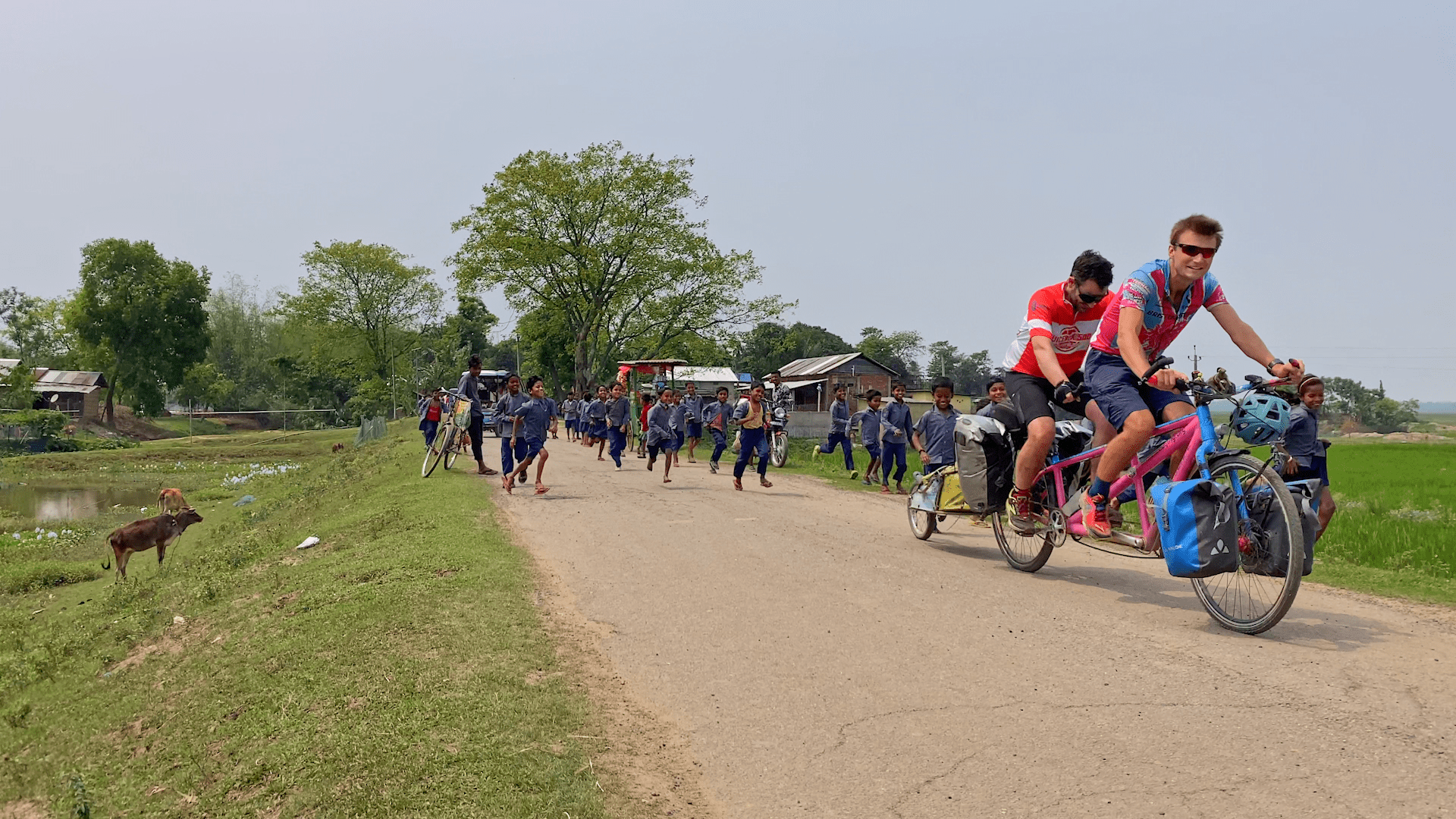

After setting off from his alma mater Bristol Grammar School, Luke was joined by over 800 people over the course of the ride, many of them fellow cancer survivors, or 'CanLivers'.

“The CanLiver mentality is all about this idea that you ‘can live’ with cancer. You can live richly, fully, adventurously, optimistically, actively. But living with cancer is also full of challenges and uncertainties. And I coined this term because I couldn't reconcile myself with the idea of being a ‘cancer survivor’, that I could somehow say I've moved on. This is a chapter or a door I can’t close in my life, so I wanted a term that both summed up the reality of living with cancer, but also the positivity that is possible.”

To begin with, Luke’s ‘joiners’ were carefully organised, with a team back home liaising and planning pickups and connections, but there were also many instances on the road when Luke would, say, pitch up at a hostel or bus stop and see if anyone fancied tagging along.

“In Uzbekistan I met a 17-year-old boy Sunnat who’d just graduated from school and who'd never been on any kind of adventure or traveled at all. He joined me from Bukhara to Samarkand, and it was amazing to watch him see his country almost from the outside like I did, seeing how friendly people were on the roads – I was learning a lot from him at the same time.

“The classic story I give, though, because it's such a clear example of what the ride was all about, is Dev. He was 17 when I met him in India, in Chandigarh. He had had cancer as a toddler and hadn't been on his bike for three years, was not a sportsman, was not very fit and had every reason not to join me – he rocked up in jeans and a jumper, good to go – but he cycled with me for a thousand miles across India. Sure, it was really tough for him, his bum was hurting and he was out of his comfort zone, but that was exactly what this trip really stood for, it was really special.”

Long before he’d met Dev or seen any of the Silk Road, however, another curve ball was hurled in Luke’s direction as Covid-19 stopped the world in its tracks, and he was forced to return home, his dream on hold. For a person living in three-month chunks at a time, those five months between pausing in Germany and getting going again felt like an eternity, but he wasn’t ready to leave it behind.

“It looked like it was going to be really difficult to continue at that point, but I think John was very much in my mind and I didn’t know if I’d ever get another chance to do it. Even so, I didn't really expect to get beyond a country or two down the line before it all stopped again.”

Luke continued to have scans every three months – in Bucharest, Tbilisi, Almaty and Kolkata – as he made it through the remainder of Europe and beyond. It’s not something most people have to think about in planning their adventures, but for Luke, the scans were one of the easier parts. With charitable motivations and a story to tell, his ride was punctuated with school talks, fundraising, embassy and hospital visits, media and radio interviews, and with his purpose displayed on his jersey and all over his equipment, he found himself telling his story more often than intended.

“I wanted the ride to put a smile on people's faces,” Luke said, explaining his choice of pink and blue as the Bristol2Beijing colours. “I wanted it to be bright, to be happy, and to make a statement. I wasn't doing this ride to sort of hide away. But the reality is always more complex because you’re riding this bright pink tandem around and after a while, you're like, I don't actually want to tell every stranger I meet about my cancer, I just want to buy the ice cream, and that was a tension that remained throughout.

Luke often found that he was pretty maxed out by the “cancer element”, all the school and hospital visits, as well as working towards the film and book. This, and some of the necessary diversions, also meant that Luke didn't get to spend as much time as he might have liked focused on the Silk Roads, though experiences in Georgia and Pakistan brought the Chinese influence to mind, for example, the Chinese Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

“Apart from the fact that I knew the road we were cycling on was Chinese built, it wasn't that obvious that there was a Chinese presence,” Luke said of the ride down the Karakoram Highway with his uni friend TJ who was a ‘joiner’ for a 700-kilometre stretch through Pakistan. “We ended up having to stop in this town deep in the mountains and our security escort was very unhappy. They’d been with us for a few days – a rotating guard with an AK-47 on a motorbike at all times, and quite often we also had a police truck with four guys in the back, also with AK-47s. They really didn't want us to stop, but it was 10 at night and there was no way we could go any further. We found out why the next morning: there had been a suicide bombing on a bus full of Chinese workers that were building a hydropower station. That's the only way I really heard about any of that work.”

Any great adventure demands an adaptive mindset, and Luke faced plenty of obstacles, dozens of punctures and broken rims, as well as multiple route changes, and more-than-usually complicated border crossings as he pedalled ever closer to his destination.

"I think I was in India by the time Omicron came around and the world was about to shut down again. At the time I was trying really hard to get the permissions to get into China. We were very optimistic because I'd gone through nine countries that were already officially closed, but I'd managed to get special permission from ambassadors or the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and some big names trying to support us, so we really thought we could do the same thing here. But with Omicron and then Shanghai shutting down, China remained impenetrable.”

Luke and his team back home were met with a dilemma. One option would be to hole up in Bangkok and wait it out for a few months, then see if he could make his way into China from Singapore, but more ‘waiting’ was not a particularly attractive proposition.

“The decision I came to, rightly or wrongly, was to take control of the circumstances that I was in. I can't control whether China opens its borders, so is there a way that I can satisfyingly bring this adventure to a close in a way that I feel is right for me? Ultimately, that meant doing the final 3,000 kilometres in London with the tandem on the turbo, and inviting everyone to join me there.”

In completing Bristol2Beijing, in his own way, Luke achieved another milestone that had for him – like completing his MSc – a special significance.

“Again, I did not think I'd get to the end. My mum articulates this very movingly in the movie on the day of the ride’s launch in Bristol. She says ‘my friends asked me if I was looking forward to seeing Luke finish in Beijing, but they just didn't understand that Luke wasn't going to get to Beijing, he wasn't going to be alive.’ I only found that out on the penultimate day of the ride during a radio interview, but I think it frames it more effectively than I can.”

Into the unknown

But he made it and then it was all over, and in a way reminiscent of Olympic athletes who come home after their first Games or their first gold, Luke found himself enduring a difficult period in the months that followed. There was a consultancy job waiting for him which remained an option, but he was perhaps not the same person who had left Bristol two and a half years earlier. ’What’s next?’ suddenly had no clear answer, and but for a desire to perfect his latte art, the curious and precarious reality of his life was without a central goal to focus on day to day.

“I think I've been finding my feet ever since then. I had been living my dream of riding to Beijing and I never questioned what I was doing – that gives you an enormous self-belief and energy and confidence. I’d gone from often being treated as a Z-list celebrity to a normal person in a normal life, working in a coffee shop in London. I’d had so much clearly defined purpose and now when people asked what do you do, my answer was ‘I don’t really know’…”

The desire to turn the footage he and director Mike Rumsey had collected into a film provided some impetus, and making the book a reality too, but a real shift came with the rekindling of an old flame that was his competitive spirit, something he shared with his brother.

“In the months after finishing the ride I wasn’t enjoying London, I think I was borderline depressed, I wasn't excited to get out of bed, I was snoozing the alarm. It wasn't anything terrible, but I wasn't happy. Then this race came along. I wasn't keen to do it, but I had signed up to do it with friends, so I went out to Ireland for the EcoTrail Wicklow, an 80-kilometre trail race. I was on the start line with really no idea how it was going to go, and I heard there was some sort of world record holder there [ed. - Ricki Wynne, world record for the most vertical metres climbed and descended on foot in 24 hours]. The race started off pretty quick and I was thinking, goodness, everyone's going out pretty hard, and then after seven or eight K everyone else started going slower, but I was thinking, I don't need to go slower, I'm going to keep going at this pace.

“So I went off by myself and had the most amazing day, really just filled with a lot of gratitude and joy honestly, just being without my phone and in these beautiful rolling green lush hills. And then winning this race, being in the lead – ‘What is going on?!’ This is amazing. It's mad. And I won the race by about an hour and broke the course record by about the same amount. It was really the first race that gave me the belief I could become very good at trail running.”

Though Luke stopped short of agreeing he’d found a new purpose in life, it's that race that paved the way to the present day as a sponsored athlete who doesn’t just race, but medals in events all over the world. It was also another of those days on which he felt John’s presence and perhaps finally, a chance to grieve.

“I was on the phone to Mum afterwards and I was like, ‘John would be so proud of me’, and then I broke down in tears. I did not expect that, but it’s in those moments that grief for John has hit me, in those situations where I feel his presence.”

As we’d talked, it had become clearer and clearer that my assumptions were all wrong. Here was a man who I expected to delight in escaping reality – re-defining himself at Oxford; literally riding away from Bristol where he’d been diagnosed and treated for stage IV cancer; becoming a trail runner with a definitively nomadic, sofa-surfing lifestyle – and yet the more we talked, the more I realised he was on a quest for the exact opposite.

“I wouldn’t frame it in those terms,” he began when asked if he sees exercise as a means of escape. “Exercise is almost the opposite of escapism for me, because to run for multiple hours, say 10 hours without any distractions, there's plenty of time to confront demons and to be in your own head.

“But having cancer you become very aware of the question, ‘what if I die tomorrow?’ And will I be happy with how I’ve spent today? I’ve tried really hard to create a life for myself that I don’t want to escape, a life that I enjoy and value every single day.”

Luke’s description of his very purposeful life is fuelled by a unique relationship with time and a profound relationship with his body.

“At its heart for me, living positively and optimistically revolves around physical activity,” he summarised, pointing to the Move Against Cancer charity for whom Luke is now proud to be a patron, and whose work emphasises the value of getting the body moving for those living with cancer.

“For me running or cycling doesn't have any inherent meaning. I enjoy it. I love it. But for me it's always a base for something that does carry more meaning for me. If I talk about how I train, or winning a race, why does that matter any more than anyone else winning a race? It doesn't really, so what are you doing with that platform? What's the wider story?”

The wider story for Luke is reflected in the decision to ride a tandem to Beijing: an experience shared with other people, and especially those who are not just surviving, but living with cancer.

Did we do a good job with this story?