It’s August 1912, and the Estonian photographer and filmmaker Johannes Pääsuke is on a field trip. He is his country's earliest adopter of a nascent art form – although he's just 20 years old, he’s been shooting for five years. It’s equal parts art and manual labour: his camera is big, and it is heavy, and it is on a big tripod. He points it, captures a frame, and at some point thereafter develops it and hopes that he likes what he sees as his vision blooms across paper in a darkroom.

Despite his youthful inexperience, Pääsuke does not lack confidence in his craft: he will soon approach the Estonian National Museum and be commissioned for a major project, to document Estonia’s people, places, and industries – a national ethnographic project which will take him across the south of the country, resulting in 1,300 glass frames and photographs of forgotten faces. That is in the future. Today, he is hot, he is two days’ cart-ride from home, he is being strafed my mosquitoes, and he is bearing a hefty burden of equipment and dreams. And then he sees the boy.

We don’t know where the boy was, exactly; only that the photo was taken in what was Tarvastu Parish, a now-superseded regional area near the shores of Lake Võrtsjärv in present-day Viljandi County. Tarvastu itself – a tiny town sharing its name with the parish – is an ancient settlement with a historic castle nearby, and the Tarvastu river languidly flowing past into the lake. In summer, the foliage hanging over the river bursts forth in life, casting the scene in golden-green. By the time of Pääsuke’s visit, the 14th century castle is already crumbled into constituent materials, little more than a clump of formed stone overgrown with weeds. Like a lot of Estonia, Tarvastu Parish is flat and pastoral and, at this time, desperately poor, necessitating a pragmatic hand-to-mouth existence. Those are circumstances that explain, perhaps, what the boy has built and why.

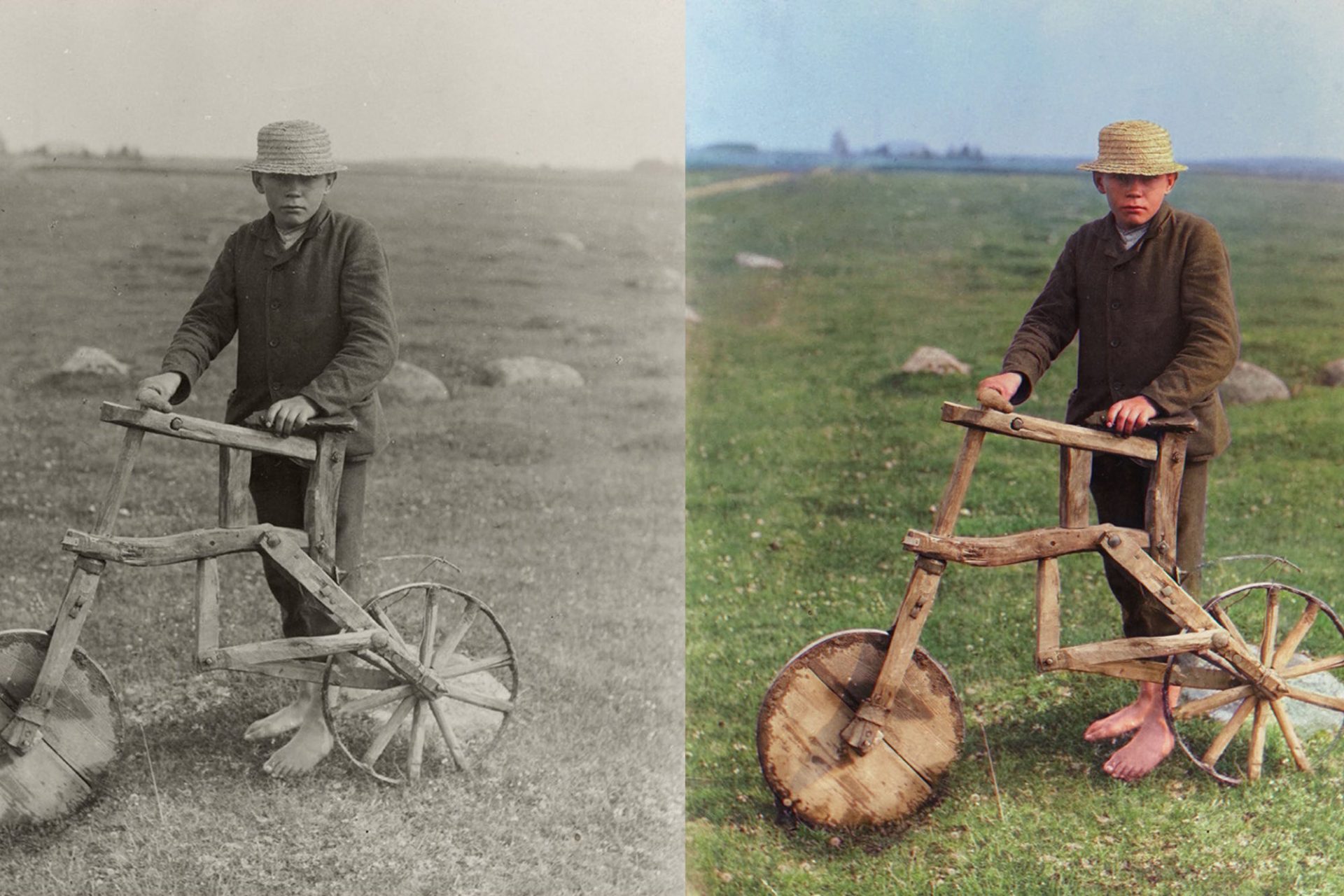

It’s a wooden bike, and he made it himself. He’s 10 years old, 12 maybe. On his head is a round hat fashioned out of straw, pulled down low. His feet are bare. He’s wearing a little suit of scratchy wool, a collarless shirt done up to the top button. He rests one hand on the seat (wooden) and one hand on the handlebar (also wooden). Crude boltheads run through the frame, holding top-tube to seat-stay to wheels. There’s no pedals – it’s like a Karl von Drais swiftwalker transposed a century forward in time and across to rural Estonia, then part of the Russian Empire. On one hand, it’s easy to describe the boy’s bike as laughably primitive, but that does not do it justice, because he is just a boy and he has built this little miracle himself with knives and hatchets and offcuts.

And so, on this day he stands there in a field, staring down the barrel of Pääsuke’s camera. He does not smile; in fact, he looks kind of sullen. Maybe it’s the first camera he’s ever seen; maybe he’s suspicious of the young man from the big smoke of Tartu appearing in his day and interrupting his play. In this child from 110 years ago, there is something foreign and otherworldly, but something universal too – something that you can see in any child with something that they care about, that they've effortfully crafted. There’s a defiant pride, I think, in the way he holds his creation. It’s not much, but it’s his, and for the time Pääsuke is taking his picture, he is showing it to the world. This is mine, and I made it. My bike.

Behind him is a field with a few rocks scattered about. There’s the suggestion of a road cutting across the top left corner, and on the horizon is the suggestion of a town. The boy is anonymous, the scene is anonymous, and when you scoot around Tarvastu on Google Maps now everywhere looks more or less exactly like it did 110 years ago. But as little as some things might have changed over the intervening years, a lot has happened in this sleepy pocket of Estonia.

When the boy was born, some time around the turn of the century, Estonia’s cultural identity was actively being suppressed, with a program of Russification adopted by local governors under the thumb of a distant Tsar. By the time the boy was five or so, the first Russian Revolution led to calls for press freedom and national statehood. In Tartu, Pääsuke’s hometown, a multicultural student population was at the forefront of this resistance. The privileged young photographer was at the nexus of two worlds: reaching out to and documenting the common folk in the countryside, while representing a more elite urban class. The boy was just a boy, frozen in a frame from more than a century ago.

So I wondered what more there might be to his life. Whether that early experiment in bike-building led to an interest in cycling, and if or when he’d graduated to his first real bike. I wondered how he would have held the handlebars and saddle of a machine made out of steel with cranks and pedals, whether there was the same fierce pride then as there was in the summer of 1912. I wondered whether he considered Russia home, or Estonia, or neither, or both. I wondered whether war exploding across the continent a couple of years later drew him into its orbit; whether he suffered seasons of hardship, or stayed safe from horror in his peaceful hamlet near the river and the lake. I wondered if he stayed there forever, or whether he was driven away in search of a better life. I wondered what he thought as his country was occupied, became free, was invaded by Soviets, invaded by Nazis, then reclaimed by the Soviet Union again. I wondered if he lived to see independent Estonia in 1991. I wondered what his name was.

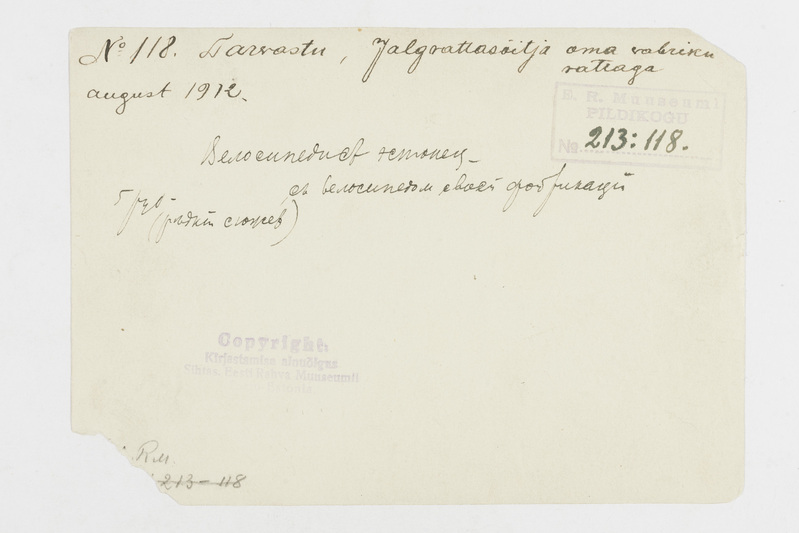

When I contacted the Estonian National Museum they gave me what they had: a scan of the original picture (11 x 15 cm, torn in the top right and bottom left); a scan of the hastily scribbled note on the back presumably written by Pääsuke, giving a location and a month. “Unfortunately nothing more is known,” the archivist told me. Tarvastu was a dead-end, too – the town has fewer than a hundred inhabitants today, and a hopeful email to a bare-bones local tourist website went unanswered.

The man behind the lens, Johannes Pääsuke, is a bit easier to pin down. There are pictures of him, a haughty young man with a documentarian’s heart: the first Estonian film-maker, his life later the inspiration for a fun-looking 2019 comedy film. His vast catalogue of work has been published in books, providing the defining insight into the lives and attire of the Estonian peasantry through the era.

In a just world, Pääsuke would have had a full and prosperous life. But war does not discriminate: after being drafted as an infantryman for the Lithuanian Regiment of the Foot Guards, he found himself in St Petersburg by the end of 1915, fighting in a war for the fading empire that ruled his people. By January 1918 he was dead, killed in a train crash in distant modern-day Belarus. He was 25 years old.

Recently, the boy with the wooden bike was unearthed from the dusty archives his photo has been living in. An Italian graphic designer, Lorenzo Folli, took the black and white image and colourised it: gave the bike's wood its golden hue, coloured in the field behind the boy, breathed warmth into his frozen face. Yesterday, the History in Color Instagram page reposted the image to its 1.8 million followers.

And so, Johannes Pääsuke’s work is, briefly, current again – shared around a world he would not recognise, several lifetimes away from his brilliant young life and violent end. The photographer is long gone and so are the subjects of all of his photographs, including the boy with a wooden bike. But for this brief moment, both the photographer and subject's creativity, ingenuity, pride and defiance is there for the world to see. A homemade bike that was nothing much, but for one person meant everything. A picture full of meaning, just waiting to be found by whoever needed it.

In Tarvastu, the roads are still gravel and the fields are still green. Life goes on, even when it doesn’t.

Did we do a good job with this story?