What have we just witnessed? That question was on many people's lips following Jonas Vingegaard's dominant display in the stage 16 time trial. While the Twitteratti may come to one conclusion, throwing the dummy out of the pram isn't an option for the top WorldTour teams. With Jumbo having two riders on the time trial podium and an utterly dominant display from Jonas Vingegaard throughout July, you can be sure the Team UAEs, Ineos Grenadiers, and the rest are already reviewing and assessing how they can close the gap before next July.

Much has been made of the 5% gap between the previously inseparable Vingegaard and Pogačar. With such domination, it's only right and natural the watching public ask some difficult questions. Especially when the guy at 5% was himself head and shoulders above the rest of the competition. We won't address the physiological side of that question here; instead, we'll delve into the technical and equipment aspects that could explain some of that gap in performances.

More importantly, bearing in mind the 2024 Tour de France will finish with a similar 35 km hilly time trial around Nice, how do Pogačar, UAE, and everyone else close that gap before next July? Having had five days for that time trial performance to sink in and spent countless hours on the phone and recording podcasts since, here is some of our conclusions.

What we know

Vingegaard achieved what many are describing as the best Tour time trial performance of all time. What technological advancements and preparatory work by Jumbo-Visma could possibly explain a 98-second gap to second place in just 22 km? Before jumping into the hypothetical analysis, let's briefly recap what we know with certainty.

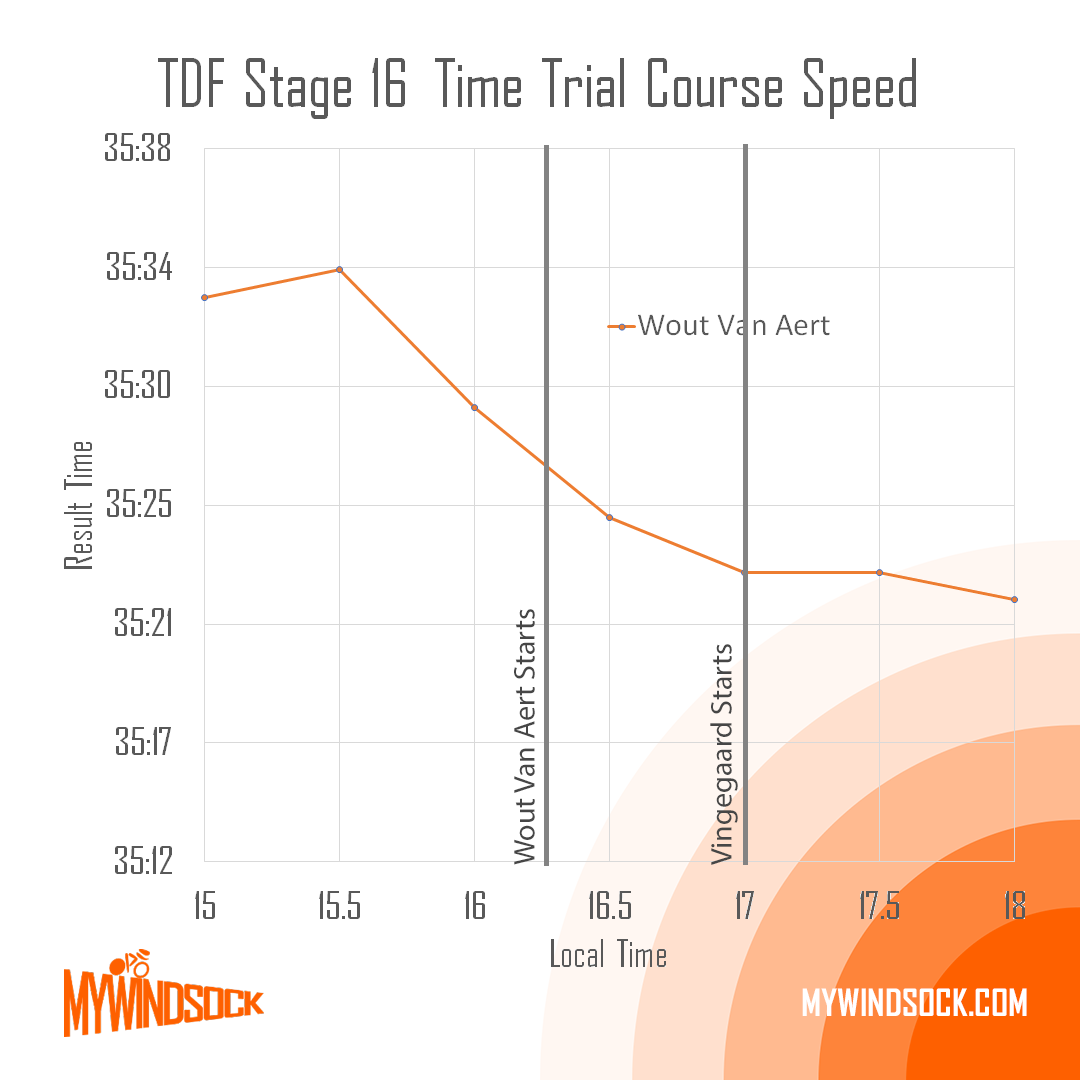

It's important to first recognise the unique circumstances surrounding stage 16. Both Pogačar and Vingegaard were more than head and shoulders ahead of the rest of the peloton throughout this Tour. Every time the road tilted up and they were racing in anger, there was rarely another rider within touching distance. Granted, this very fact opens a host of questions in itself, but what is indisputable is that the parcours for the stage 16 time trial was always going to accentuate the dynamic duo's performance advantage even further. With two climbs and two climbers at the peak of their powers (so far), no one else stood a chance on this stage. Even the flat sections didn't offer much chance to the traditional time trialist, as we will learn later.

As for Jumbo-Visma's preparation and attention to detail, that was evident from the second Vingegaard rolled down the start ramp. If the Cervelo P5 sans paint wasn't evidence enough, the speed with which Vingegaard took the first corner and, subsequently, the descent off the Cote de la Cascade de Cœur made the team's focus evident. Vingegaard extracted every second and exploited every inch of the road as he descended at a pace that, even on TV, was visibly much faster than almost anyone else.

This wasn't just a display of descending prowess, though. Having a rider with exceptional technical ability on the time trial bike is just one part of the equation, as Mathieu Heijboer, Jumbo-Visma's Head of Performance, was eager to point out when I spoke with him 24 hours after Tuesday's time trial. Heijboer had just returned home, his work at the Tour complete, and pointed first to the team's time trial recon when asked what steps the team took to prepare for this time trial. Heijboer and Vingegaard had reconned the time trial earlier in the season and again on the rest day, both times on open roads, before reviewing the route again on Tuesday with closed roads. Not really anything above and beyond what we would expect from a Tour contender. Where Jumbo-Visma's approach seems to have differed is what they did after those recons.

Fast forward to time trial day, the team, with feedback from Jonas on the course during the closed-roads recon, had made a detailed analysis of every corner analysing racing lines, braking points, and turn-in points, down to whether a corner could be taken in the time trial extensions or if it would require Jonas to sit up onto the base bars. These details would be used later as a form of pace notes for the team to deliver to Jonas during the TT. The team also recorded the closed-roads recon for Jonas to review over and over back in the hotel. Long story short, Vingegaard knew this TT course like the back of his hand by the time he lined up on the start ramp.

Skipping forward to the actual time trial, the team had Christophe Laporte race the descent "full gas" in a final test of their pace-notes strategy and effectively test if the risky-but-rewarding descending strategy was achievable without crashing. Laporte hadn't even ridden the descent in the morning recon, preferring to save his legs than ride another climb when he had an opportunity to rest. Surely this faith in the team's instructions must go down as one of the more dedicated team support roles of this Tour de France. The gain wasn't massive, maybe a handful of seconds, but it 1) indicates Jumbo-Visma's extreme attention to detail and diligent prep work and 2) every additional second Vingegaard had at a time check was a little more pressure heaped onto Team-UAE and a little lifted from his shoulders. It all added up.

"Does Jonas have any drop off in power from road bike to TT bike?" I asked Heijboer.

"No, no, no no, no," came the emphatic answer, "and especially not on the base bar."

Vinegaard's exceptional ability to maintain his aero position was also evident during the entire time trial. It's one thing to be aero, and another to produce power, but combining the two is the secret to successful time trialling. Rarely do riders look as in tune with their TT bikes as Jonas did on Tuesday. Perhaps only Hour Record holder Filippo Ganna is on a similar level. "Jonas is doing a minimum of two, usually three sessions per week on the TT bike totalling roughly five hours per week," Heijboer told Escape Collective when asked how much training time is required to get that efficient in the time trial position. "We did not compromise on aerodynamics."

To change bikes or not for the second climb was the big question of the day for many, but not Jumbo. In fact, as Jumbo saw it, even considering a bike change was asking the wrong question entirely. Heijboer explains how the team decided as far back as Paris-Nice that a bike change would be the wrong option. The bike-change question is actually a weight-saving question, and with the upper limit of weight savings capped by the UCI weight limit, a light time trial bike was the solution, not a bike swap.

A bike change was never in our heads.

-Heijboer

That, is of course, an obvious answer, but it's only the answer when the question is how do we go fastest instead of which is fastest? Asking the right questions and getting the answers, Jumbo had Cervelo deliver an unpainted frame (just a clear coat) to save "around 100 grams" according to Heijboer, and then proceeded to cut the seat post to the absolute minimum and rework the mono riser-to-extension interface to save every gram possible. The team also used lighter brake rotors, pads, and most likely SRAM's new unidentified cassette. Reserve's 77 front and disc rear wheels are also sub-2,000 grams for the pair and yet impressively wide at 31 mm external rim width on the front and 30 mm at the rear. That width means the team can run wider tyres and still maintain an optimal aero interface between tyre and rim. On that note, Vingegaard and Wout van Aert both had new 26 mm Corsa Pro Speed tyres from Vittoria. If that "Speed" moniker is anything like Vittoria's existing Speed range, that will be a light tyre with exceptionally low rolling resistance.

All told, Vingegaard didn't only exhibit exceptional aero position discipline, on an exceptionally aero setup, but it was also likely one of the lightest TT bikes available to anyone on the day. If I were to hazard a guess, I'd assume Vingegaard's bike was around ~200 grams lighter than the 8.18 kg we know Roglic's standard team issue P5 weighs and is probably among the lightest at the Tour this year.

He produced his best numbers ever, it was a really special day. That was the biggest difference of all.

-Heijboer

What is also special? Vingegaard gave away more information than most in his post-stage 16 press conference. The Dane revealed he was planning to ride at 360 watts on the flats but was actually maintaining 380. Heijboer explained the team typically uses RPE (Rate of Perceived Exertion) in pacing time trials, a pacing strategy Vingegaard was able to fine-tune, having got it wrong in the time trial at the Dauphine last month. "We use the power meter as a reference, but most important is the feeling," Heijboer explains.

What we think we know

Using those numbers, we can make educated guesses at Vingegaard's CdA. Some of the calculations we are seeing and hearing at Escape Collective suggest that figure is as low or perhaps even lower than .17. We put this number to Heijboer, who, understandably and frustratingly, couldn't give away Jonas's measured CdA but did say, "that is close," as if to suggest the actual number might be even lower. To be clear, .17 is absolutely exceptional.

Heijboer then tells a story from aero testing Jonas's time trial position during covid times, the aerodynamicists back at home were convinced there was something wrong with the test or equipment, so low was his CdA. These are only estimates, but for comparison, Dan Bigham's CdA for his successful Hour Record attempt last year was possibly as low as .155. Remco Evenpoel's CdA is perhaps similar to Vingegaard's, while Ganna's Hour Record CdA is estimated at .185 (a rider's CdA is typically lower on the track due to the clutter-free track bikes, but Ganna is also 18 cm taller and roughly 20 kg or more heavier than Vingegaard). Finally, Van Aert – a similarly sized rider to Ganna – has an estimated CdA of perhaps around .2. For what it's worth, some calculations suggest every .01 increase in Jonas's CdA could have cost him as much as 24 seconds. For comparison, each extra watt would save 2.9 seconds. Hence the importance of maintaining the optimal time trial position.

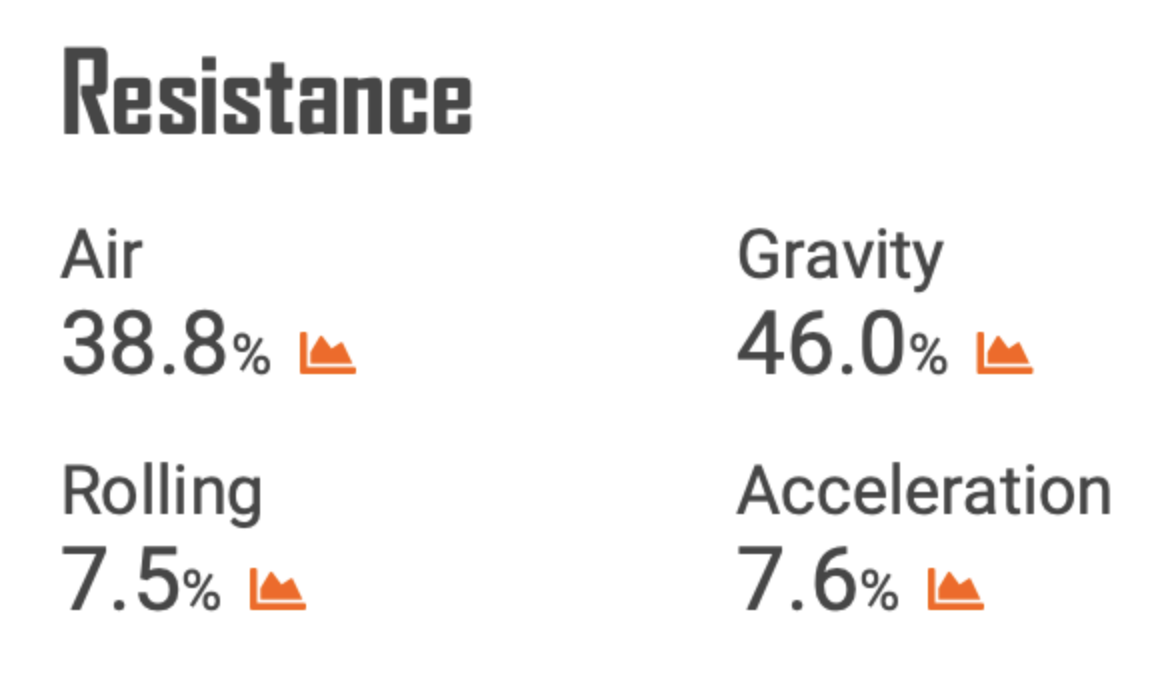

Indulging in these somewhat hypothetical numbers even further, 380 watts and a CdA of .17 put Vingegaard at 2,235 w/m2 (think w/kg but for aero). How much better is that than the others? Well, some sources suggest Vingegaard's figure is 174 w/m2 higher than Pogačar (2.061 w/m2) in second, and 303 w/m2 over Van Aert (1,932 w/m2) in third. It is important we caveat these numbers once again with the reminder we have not seen a power file for any of the podium finishers and these calculations are highly affected by changing wind conditions. A 1-2 kph change in wind speed could result in a 3-5% change in CdA. Even with power data, we would also need a total system weight for each rider on the day; rider weight alone is not enough. That said, more w/kg on the climbs and a better w/m2 in the TT position is the perfect combination for a GC rider to destroy the competition, especially on such a favourable course.

How do the rest catch up?

None of these "hacks" are a silver bullet; none could overturn Pogačar's deficit on Tuesday despite the fact Pogačar was himself head and shoulders above the rest of the Tour de France field. But just as the entire cycling world is growing sick and tired of the mention of "marginal gains," Jumbo are maximising every marginal gain like no team has previously.

Perhaps it's as simple as how each rider dealt with the rest day. Perhaps Vingegaard recuperated better and improved to have a tremendous day on stage 16, while Pogačar backflipped into a pool and front-flopped into the time trial? Please, never change, Tadej. Perhaps a complicated wrist break in May and subsequently interrupted Tour build-up finally caught up with Pogačar. Only UAE know how good or bad he was on stage 16 this Tour compared to his potential. If Pogačar was on a bad day and on another day both riders enter the stage 16 time trial at peak powers, that's when these hacks matter most. What are UAE doing now to ensure Pogačar's best legs have the best support structures the next time his sublime talent is not in itself enough to demolish a Tour time trial?

We spoke to Marc Graveline, inventor of the Notio Konect aero sensor and aero consultant to WorldTour teams, for this week's episode of Geek Warning. Marc is an Escape Collective member and was all to happy to geek out with us on all things aero and time trialling.

We put this question to Graveline on the show and the answer led us down many rabbit holes. One takeaway I had from a pre-show conversation with him was just how far ahead Jumbo-Visma might be. While it is difficult to assess the inner workings of every team, Graveline suggested one rival team is only using "one of the greatest aero minds in cycling" to about 20% of its capacity.

There's less analysis than people might assume. Many teams are simply following the lead of whoever is quickest

Marc Graveline, Escape Collective member and aero consultant to WorldTour teams.

It doesn't take a great aero mind to understand every team and manufacturer is now acutely aware of the benefits of aerodynamics. What is less obvious is how much the teams understand this most complex of subjects. While many teams are struggling with the basics and copying others, Graveline is trying to communicate the individuality of aero and the importance of wind tunnel-to-road correlations and "closing the gap."

Take Pogačar's bike change, for example. Scanning the Team UAE Emirates website, it is not immediately clear who would make such a decision. There are no aerodynamicists, performance engineers, or data scientists listed among the team's staff positions. There are no Dan Bigham's or Marc Gravelines, no Mathieu Heijboers or Martin Toft Madsens. In fact, most of the "technical staff" are sports directors and former riders. When asked, UAE told Escape Collective that former pro David Herrero oversees the team's aerodynamic, analytical, and performance engineering requirements, which seems like a lot for one person on one of the world's biggest and best-resourced teams. Rumours also suggest the team is already working to bolster its technical support structures.

Modelling the Côte du Domancy is almost impossible given the speeds at which the riders came into the bottom of the climb, and of course, we will never know for certain how much time Pogačar would have lost or saved by sticking with his time trial bike. But for what it's worth, we estimate the road bike might have been 5 seconds slower, including the bike change. Including the bike change is obviously essential here, and something that seems to be lost in some of the discussion since on Pogačar's time for the final climb.

But aero minds are only one part of the equation. Processes are also key. To UAE's credit on the bike change, they thought they were making the right decision, taking the faster option, and they stuck to it. Suggestions they should have scrapped the bike change when Pogačar was already losing time are losing sight of the fact one only does a bike change if they think it is faster. When you are losing time is exactly when you really need to do what you believe is fastest. The bigger problem is again how they came to that conclusion. Is that indicative of how other aspects of the team are run? Good sensations rather than solid science?

Is anyone giving Pogačar pace notes on the descent? Clearly no-one had pushed Colnago to produce a lighter TT bike. The team had taken some weight-saving measures but left others on the table. Heck, some manufacturers are reported to have created special frames with exotic carbon layups to get aero bikes down to the UCI 6.8 kg weight limit.

The same goes for other teams. Every team bar Lidl-Trek and Groupama-FDJ restrict their rider's time trial helmet options to those on offer from the team's helmet sponsor. Ineos-Grenadiers are a little different in that Kask seems to make as many different time-trial helmets as the team requires. But of the rest, there is zero chance one TT helmet is the fastest for an entire squad or multiple squads.

I recently spent an afternoon on Derby Velodrome aero testing with Wattshop in the free time between a friend's aero testing runs. That short period on track was enough for me to test a box full of different time trial helmets and a couple of positions. I left that session knowing the fastest helmet for me (A Kask Mistral if you are wondering, closely followed by the Kask Bambino) and a whole host of experiences and further understanding on all things aero.

MET has one of the widest ranges of time trial helmets of any brand, but is the Codatronca Tadej races with tested as the fastest for Pogačar? Possibly, but I don't ever recall hearing or seeing any images of Pog in a wind tunnel. Of course, just because UAE don't shout about it doesn't mean they haven't got it clued in, and furthermore, it didn't matter before. Pogačar could rely on being the best rider in the world, by a considerable margin, for his first two Tour wins. But Jumbo changed the game last season and has pushed it even further this year, the rest have no option but to catch up.

What they lack in helmet testing some teams make up for with frames, or clothing, or wheels, or cooling, or training, and so on. But Jumbo, while not ticking all the boxes, does seem to be ticking the most boxes. Surely everyone in the WorldTour has heard of the "stacked roof rack hack" by now. It was only this week that Bert Blocken, an engineering professor at KU Leuven and aerodynamics consultant for Jumbo-Visma released a study on the benefits of having a roof rack full of bikes in reducing a rider's aero drag. Long story short, it's a tiny gain, but a gain nevertheless, where was Pogacar's stacked roof rack?

We could delve into bar width, tyre width, rim widths, tyre pressure, handlebar widths, aero shoes, Jumbo's warming up gazebo with giant mist blowing fans versus many teams setup in the blazing sun etc etc etc. You get the point. To my eye, Jumbo-Visma are the one team getting the most right the most often. And that's only of the stuff we can see.

Worryingly for other teams, Heijboer is already talking about learnings for next year's final time trial. "Stage 16 was not an endpoint, we have other things in the pipeline for future time trials."

If any one thing made the 1:38 gap between Vingegaard and Pogačar on Tuesday, it was Vingegaard himself. The same can be said of Pogačar himself in many races. These phenoms are few and far between. As Ineos are now reportedly considering a big-money swoop for Remco Evenepoel, is anyone at the Grenadiers headquarters asking how they missed the two, or three (if we include Remco) or five (if we include Van Aert and Mathieu van der Poel, this is an incredible generation) best cyclists ever to grace the peloton in the first place. Jumbo has two of these phenoms, UAE has Pogačar and snapped him up early, but other teams seem left behind.

Like it or loathe it, the game has moved on. Jumbo may have a world-beating athlete with supposedly the second highest Vo2 ever recorded, but before we cry foul, we, and especially the other teams, need to assess every element of performance. Teams need to peg Jumbo's advantage to just the rider and eliminate the additional losses that are theoretically there for the taking. Speaking of the physical, some of Jumbo's training techniques are fascinating, and we hope to bring you more details on these as we get them.

Did we do a good job with this story?