Remember those prototype Ekoi pedals that surfaced last week? Well, they are making headlines again, this time for less exciting reasons. As reported by MatosVelo.fr over the weekend, the UCI commissaires at the Etoile de Bessegges stage race intervened to prevent Team Nice Métropole Côte d’Azur from using the new pedals in UCI-sanctioned events. The change reportedly came within one hour of the start of the race and left the team and riders scrambling, and not only to find different pedals; because the system incorporates the cleat into the sole of the shoes, the riders also needed to find new shoes.

Thankfully other teams and local shops came to the rescue and the team was able to take the start, but imagine having to set up new shoes and pedals moments before a race. That sounds like a recipe for injury.

With talk of an eight-watt saving and a radical new design, the pedals successfully broke the internet last week. As such, it may come as little surprise that the UCI stepped in to spoil the fun. But before we chalk this one up to just another reason to pound on the UCI, this one is on Ekoi, the manufacturer, not the honchos in Aigle.

How so? Well, for once, the UCI’s rules are pretty clear-cut, and the UCI has merely acted in accordance with said regulations. The issue at hand is the use of prototype equipment not yet available for purchase through commercial channels. Article 1.3.006 – the “commercialisation rule” to you and me – clearly stipulates how and when prototype equipment may be used, and it is the team’s and manufacturer’s responsibility to know and understand the rules.

How the rules work

There is no outright ban on the use of prototype equipment, except in track record attempts, and from what we understand, the UCI has not banned the new Ekoi pedals. There is, though, a very clearly defined process governing the use of prototype equipment in UCI-sanctioned events, which Ekoi has seemingly not followed.

The basic principle of article 1.3.006 is that all equipment used in professional racing must be available for a member of the general cycling public to purchase and use. The first line of the rule encapsulates everything the UCI wants this rule to ensure: “Equipment shall be of a type that is sold for use by anyone practicing cycling as a sport.” The following five paragraphs then seek to clarify how and when prototype equipment may be used in competition and a time frame within which all equipment used in competition must become available.

The use of prototype equipment in competition is an essential step for manufacturers in testing new equipment. The UCI seemingly recognises this and the value of using prototypes, but, clearly wants to avoid any equipment surprises or confusion on the ground at races, like Jan Willem van Schip’s disqualification from the Belgium Tour in 2021 having used Speeco’s Aero Breakaway bars, which seemingly either the commissaries on the ground or the team had misunderstood as approved for use.

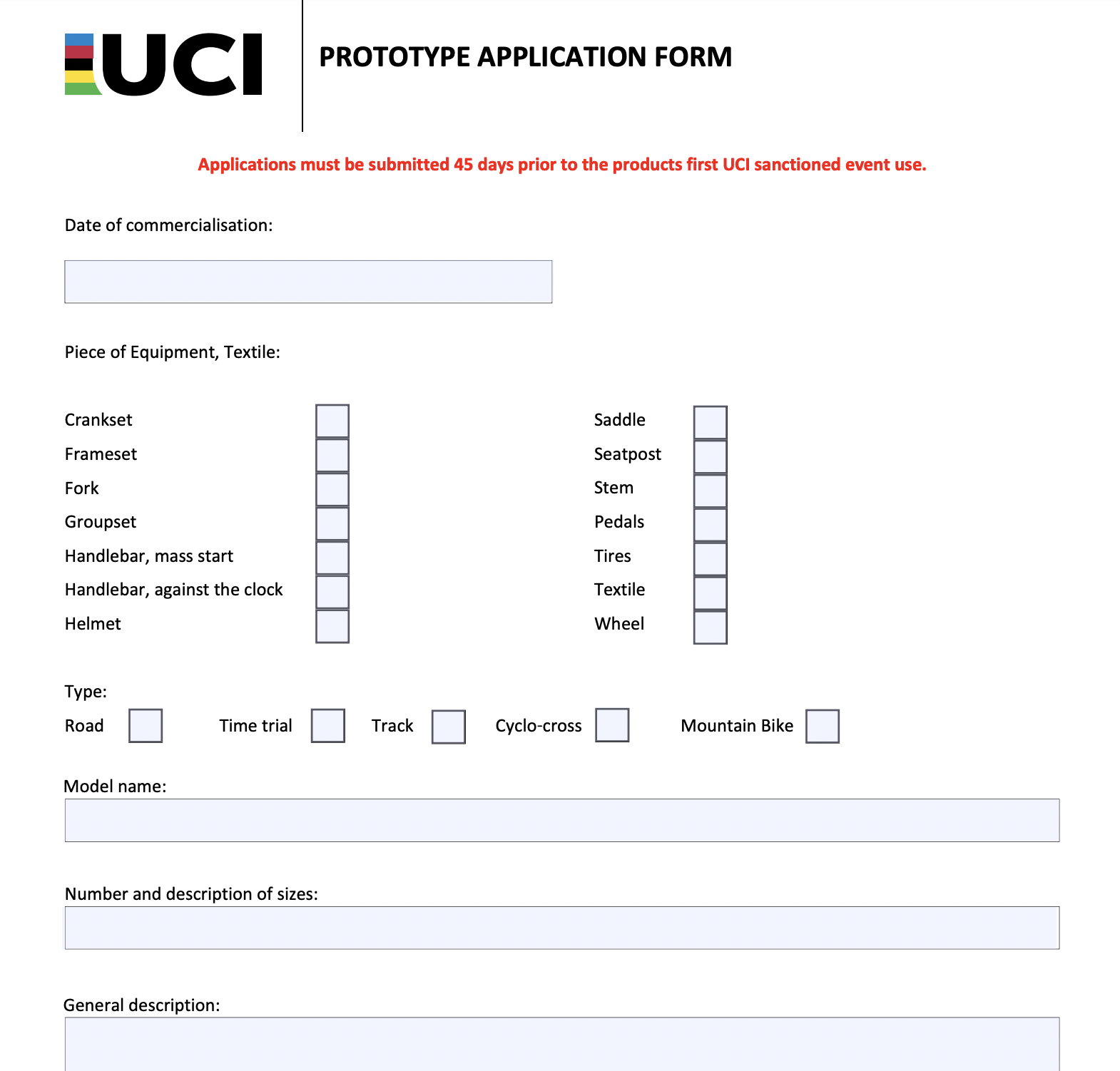

As such, the UCI introduced a channel for pre-registering prototype equipment through its “Prototype Application Form” [PDF] effective January 2023. The form requires manufacturers to submit contact details, planned date of commercialisation, details, and a description of the prototype product, including manufacturing descriptions and the types of material used. There is then a cost associated with the form submission, varying from CHF250 to CHF1,000 depending on the piece of equipment to be registered. The UCI has even clearly stated all applications must be submitted a minimum of 45 days prior to the use of any prototype equipment in competition in bold red text at the top of every page on the form. Without a publicly available register of approved prototypes, one can only assume other manufacturers have followed this process, and the UCI has given pre-approval to all the prototypes we have seen in use in competition over the past 14 months.

UCI rules and its interpretation of them can sometimes seem opaque or even capricious, but here, the process is perfectly clear. The UCI has a longstanding commercialisation rule, said rule clearly states the process for using prototype equipment in races, and the application form clearly lists pedals as equipment requiring approval. Whether the UCI is overstepping its mark in insisting on having oversight of every piece of equipment manufacturers plan to offer – right down to something as seemingly innocuous as pedals – is a fair question, but in this case the UCI merely applied its rules as they currently stand.

The UCI is not without criticism for how it handled this case, having delivered the news to the team within an hour of the race start and thus creating the ensuing rush to find replacements, not to mention potential rider injury with what must have been best guess positional setups. Reporting by MatosVelo.fr suggests Ekoi had submitted the relevant paperwork, but either not within the correct timeline or some other filing error meant the pedals had not yet been approved for use. As such, one could assume that when Escape Collective and Every Other Cycling Media Outlet published stories about the new pedals last week, someone in Aigle could have slid into the French team’s DMs to remind them the pedals are not approved for use with a little more than an hour’s notice.

Furthermore, while the UCI has the right to govern the sport as it sees fit, such needless and complex interventions merely add to the workload of what are, relatively speaking, small companies working in a relatively small industry, not to mention adding further workload to the presumably already-stretched workforce at UCI HQ. If the UCI is guilty of anything here, it is attempting the impossible task of creating technical rules to try to make a technology-dependent sport less dependent on its tech. One gets the feeling that the UCI might find cycling a lot easier to govern if it weren’t for the pesky need for cyclists to ride a bike. But alas, while that requirement exists, UCI is constantly battling to force the tech innovation genie back into its bottle.

In addition to all that extra headache, if there is an obvious contradiction in the current system, it is that it renders the use of prototype equipment testing useless for actual prototype testing. Given that only equipment in “the final stages of development” and set for release within 12 months may be approved for use, by the letter of the law, it is only products manufacturers are certain of releasing that can be used in UCI competition, arguably reducing the use of these “prototypes” to nothing more than an early marketing exercise ahead of the official launch of a new product.

A fatal flaw in the system

Add to that, arguably, the commercialisation rule itself isn’t even working. In the past two weeks alone we have seen a $60,000 Factor pursuit bike and a $7,000 Assos skin suit unveiled. These new products technically comply with the commercialisation rule, but those price tags merely serve to highlight the practically impossible-to-close loopholes that exist in the UCI rule: the products are available but are priced to effectively make them exclusive to team and federation partners. Various forms of this loophole are the main reason the commercialisation rule will never deliver the fair and equitable access to equipment the UCI wishes.

At the heart of the problem is the fact that UCI cannot dictate for what price a manufacturer may sell its products. The commercialisation rule has existed since 2010, during which time Olympic teams and manufacturers have always found ways to sidestep the rule and ensure the latest kit was reserved only for the teams it was developed for. Think Great Britain’s UK Sport bikes or Germany’s FES Olympic bikes, which technically were available to order, but with waiting times so long, you would still be waiting today for a bike you ordered in 2012.

The UCI successfully closed that loophole, stipulating equipment must be available within 12 months and mandating specific order channels, etc. But can the UCI ever dictate a third-party manufacturer’s retail pricing? That loophole seems much more difficult to close, and manufacturers are currently sauntering right through it.

Similarly, much hullabaloo was made of the UCI’s equipment register process and the requirement to use in competition (and make available for order) any equipment teams wished to use in the 2024 Olympics a minimum of 12 months out from said Games. As admirable as the idea of offering fair and equitable access to equipment is, these new rules and processes haven’t actually achieved any levelling of the imaginary playing field. That’s not a criticism of the UCI: a level playing field does not exist. It has not ever existed and likely can not.

What the rule actually achieved was in moving the cut-off date for developing new equipment back a calendar year. The richest teams, nations, and manufacturers still sit atop the R&D rich list with the fanciest of new equipment, while the poorer teams who didn’t have access previously are no better off under the new rules. If anything, they now just know their fate before the Games even begin.

How so? Take that Australian pursuit bike or the Assos skinsuit, for example: Yes, both were used (sparingly) in competition before the August 2023 cut-off date, yes both are available for anyone to order prior to the Games and so any other Olympic team or participant theoretically has access to them. But make no mistake, these items are priced solely to ensure their exclusivity to the manufacturers’ team partners. The same is true of countless other new products on their way to Paris.

You can be sure that any team with the budget to buy enough of this astronomically priced equipment to equip an entire team is already dominant enough to have their own equipment partner developing equally inaccessible equipment. Conversely, any nation that does not have such a partner almost certainly also lacks the budget to purchase said equipment.

To be clear, the biggest nations are not just supported and sponsored by the top manufacturers; they are also paying said manufacturers or, at the very least, have a national sporting body development department to lean on. Either way, there are stacks of money involved, and the UCI’s commercialisation rule, admirable as it may be, doesn’t have the teeth to intervene fully.

Is the problem fixable?

With so much national team funding linked directly to Olympic success, it seems like a classic chicken or egg scenario. How does a nation access such Olympic success-aiding equipment without first achieving Olympic success? How does a smaller nation ever achieve such success? Medals mean funding, and so medals beget more medals. This highlights the very reasons why we need the UCI and its commercialisation rules and why such interventions are hopelessly ineffective.

Arguably, it’s much more a “damned if you do, damned if you don’t” type scenario. As the “arms race” continues apace, unperturbed by Olympic cycles or UCI rules, the biggest nations must innovate or die. Getting to the top is difficult and costly, but staying there is evenly more costly as equipment that was considered advanced just a year or two ago is almost instantly relegated to antique status. Nations know their competitors are developing newer and faster equipment and so they must also submit to “technical coercion,” as Dr Bryce Dyer coined it in the UK TT scene.

What to do, though? If the UCI does intervene, inevitably they are accused of stifling innovation, overstepping their mark, and all with rules that don’t really make a difference. New rules only further empower those with the deepest pockets who can simply restart the R&D process and find the biggest gains the quickest under any new rules. Just as the smaller nations catch up and copy those with the deepest pockets as everyone converges on the fastest interpretation of the existing rules, a well-intentioned update to the regulations kick-starts the process all over again. Meanwhile, as mentioned earlier, all this development work must be bought and paid for.

Aerodynamicists, Formula One engineers, wind tunnel time, CFD experts and computing power, none of this is sponsored, and costs run into the hundreds of thousands. How are humble cycling governing bodies paying for such costs? Having sat on the board of Cycling Ireland, I dread to think, and I can almost guarantee it is at the expense of some or all forms of grassroots development somewhere else in the organisation.

The only solution I can think of is far from ideal. I propose we cap national team Olympic budgets to a percentage of governing bodies’ developmental spend or vice versa. Governing bodies can spend as much as they like on Olympic programs, but they must spend X% of that on grassroots development projects also, creating a virtuous circle of “the more you spend on the elites, the more you must spend on bringing more kids into the sport.”

Arguably even that approach only further empowers the biggest and richest nations to further strengthen their existing stranglehold on the sport, but at least there is money spent on developing the sport rather than solely on equipment and testing for a few elite athletes to use and which is out of date as quickly as it is developed.

What’s the alternative? Seemingly, there are only a few options, and they are all the worst-case scenario for many. If the arms race continues and the IOC deems events like the Team Pursuit as tests of machine rather than athlete, they might well drop it from the Games entirely. The UCI may intervene and make track racing a spec series-type event, with a set list of equipment every participant must use.

That certainly seems the logical and best answer, but as we found out last year, spec series are not without fault and arguably might not work at all in a relatively poor cycling industry. Finally, with UCI president David Lappartient also chairing the IOC’s E-sports and Gaming Liaison Group (ELG), and the IOC’s general interest in E-sports, it is not inconceivable that track cycling is replaced entirely by E-sports. While we all want to see more cycling events at the Olympics, we want those new events in addition to existing cycling events, not to replace them.

Again, it’s damned if you do, damned if you don’t. The UCI rules aren’t working, but what else are they to do? The biggest teams, nations, and manufacturers are spending mega-bucks on ensuring continued success, all the while contributing to the increasing risk that the events they are striving to win disappear entirely.

That arms-race dynamic isn’t the UCI’s problem alone; it’s also the federations. Arguably the resulting arms race is ensuring said events disappear, but what else can they do? Damned if they do and win the next Olympic gold, damned if they don’t and miss the medals entirely.

What did you think of this story?