Who truly holds the power in professional cycling? The UCI, which sets the rules for the sport? The riders, without whom there would be no sport? What about race organisers such as ASO, who own events such as the Tour de France that tower over professional cycling? Or the teams, backed by funds from moneyed sponsors who pay for the riders to be on the start line?

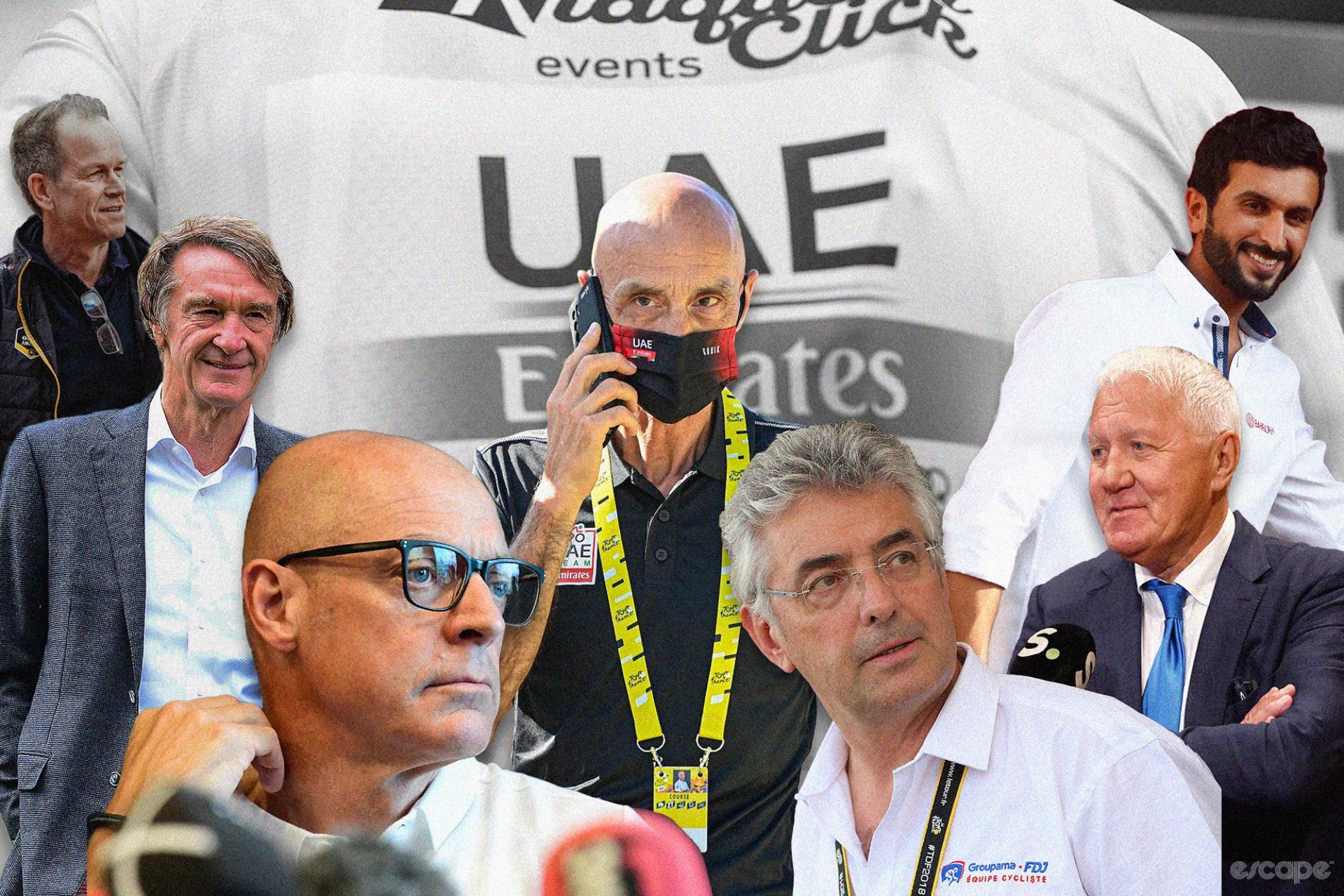

Nestled within this matrix of bike racing are the general managers and team bosses. Those who help secure the sponsors and then oversee which riders will fill their rosters and where they will race. They hold the keys to the kingdom, operate as the middlemen (they are all men), and seem to keep the many plates of WorldTour bike racing spinning. The 19 individuals detailed below have and will continue to professionally outlast swathes of riders and UCI presidents, further entrenching the power they hold.

Alongside this group of administrative apex predators are the companies that fund the whole enterprise. Their power is possibly only second to the team principals due to the singular and obvious fact that they pay everyone’s wages.

Some team bosses and sponsors you will already know – the larger-than-life characters who have been around the block and then some. But how much do you really know about them? We’ve done some digging, some rummaging around odd corners of the internet, pulling up financial statements that made our brains hurt, and have put together a picture of what the power behind the men’s WorldTour actually looks like.

Jump to a team

- AG2R Citroën

- Alpecin-Deceuninck

- Arkéa-Samsic

- Astana Qazaqstan

- Bahrain Victorious

- Bora-Hansgrohe

- Cofidis

- DSM

- EF Education-EasyPost

- Groupama-FDJ

- Ineos Grenadiers

- Intermarché-Circus-Wanty

- Jayco AlUla

- Jumbo-Visma

- Movistar

- Soudal Quick-Step

- Trek-Segafredo

- UAE Team Emirates

AG2R Citroën

Who’s in charge?

Vincent Lavenu (67) from Briançon, France, turned professional at the age of 27, winning a stage of the Volta a Portugal in the late 1980s while racing for Stephen Roche’s Fagor team. He also rode in the famous 1989 Tour de France, his one and only appearance at the Grand Tour.

After retiring in 1992, Lavenu started his own professional cycling team with a sponsor that followed him from his final seasons as a pro: Chazal, a meat producer in the French Alps.

A few years later, a chain of supermarket coffee stores called Petit Casino became the title sponsor while contributions from the public helped keep the team afloat. In 1997, Petit Casino increased its financial contribution and the squad began to compete in more prominent races before insurance firm AG2R Prevoyance replaced the coffee chain at the turn of the millennium.

Where does the money come from?

AG2R La Mondiale, entering its third decade of sponsoring the team, is a multinational firm which as well as dealing in insurance also provides financial and pension services. Headquartered in Paris – handy for the final Champs-Élysées stage of the Tour – AG2R manages around €30 billion in pension contributions (one-quarter of all employees in the French private sector) and is also the second largest health insurer, with customers totalling around 15 million.

Citroën is a French car brand previously owned by the Peugeot group but bought in 2021 (the same year they began sponsoring the cycling team) by Stellantis, a multinational car manufacturing behemoth formed by the merger of the aforementioned Peugeot group and Fiat Chrysler Automobiles. It’s the fifth-largest car maker globally with a market cap of nearly $50 billion and annual revenues of $150 billion, more than enough to chuck a few quid at Ben O’Connor and the boys. It once made the 2CV, which is now used to chuck meat sticks at children from the Tour de France caravan.

The chairman of the Stellantis group is John Elkann, the chosen heir of the Agnelli Italian business dynasty, sometimes described as “the Kennedys of Italy,” who have also owned Italian football giants Juventus for 100 years.

Owners of sponsors:

AG2R La Mondiale - Local and regional mutual insurance companies (France)

Citroën - A publicly traded company run by the Agnelli family (Italy/USA)

Alpecin-Deceuninck

Who’s in charge?

Belgian brothers Christoph (49) and Philip Roodhooft (47) are in charge of a team that has Mathieu van der Poel as the star at the centre of its solar system. Christoph is a former cyclist who raced for some smaller Belgian teams and who confessed in 2009 that the doping products (DHEA, or hormone pills) found in his house by investigators three years earlier were his.

Philip was the commercial manager for the Unibet.com team before becoming the general manager when it rebranded to Cycle Collstrop. They then co-founded the team that is now known as Alpecin-Deceuninck, starting with more of a focus on cyclocross. As van der Poel has turned his focus increasingly towards road racing so has his team, graduating from Continental level to ProTeam in 2019 and then joining the WorldTour in 2023 after amassing enough points to be promoted via the new UCI promotion and relegation system. This has signalled a growing ambition for the squad, which could previously (and shrewdly) rely on wildcard invites to any of the top races where they wanted to field van der Poel.

Where does the money come from?

Alpecin is a German shampoo brand for men that claims the inclusion of caffeine in its formula can help reduce hair loss. However, there is debate over the validity of these claims, with UK advertising standards stating the company has inadequate proof to be able to advertise its product in this manner. The brand is part of the larger Dr Wolff Group, founded in 1905, that originally produced cough syrup, cod liver oil, and various teas. One of its first big successes was an iron supplement. The great-grandchildren of the original Wolffs, Eduard R. Dörrenberg and Christoph Harras-Wolff, now run the company that has never left the family’s ownership. The company owns many cosmetic brands (including the Plantur menopausal hair loss brand that used to sponsor the Roodhooft brothers’ women’s team). The Dr Wolff Group currently boasts 675 employees located in over 60 countries.

Alpecin has a history of sponsoring cycling teams. The brand entered the space with the Giant-Alpecin team of the mid-2010s, no doubt tempted by Marcel Kittel’s luscious blonde locks, and then followed the German sprinter to Katusha. After that team folded and Kittel retired, Alpecin found a new star rider with a good head of hair – van der Poel – to fly the flag.

Co-title sponsor Deceuninck is a Belgian company that makes PVC windows and doors. Founded in 1937 in West Flanders, it is a publicly traded company with its executive chairman, the Belgian businessman Francis Jozef Willem van Eeckhout, being its largest shareholder, owning 29% of the company. The firm previously co-sponsored Patrick Lefevere’s Quick-Step outfit before switching to the Roodhooft brothers’ squad.

Owners of sponsors:

Alpecin - The Wolff family (Germany)

Deceuninck - Publicly traded company (BEL)

Arkéa-Samsic

Who’s in charge?

Emmanuel Hubert (52) is a former French cyclist from Brittany who won the national time trial championships in 1994 and the Tour de l’Ain in 1995 when he was part of the infamous Le Groupement team, which folded a week before its debut Tour de France following allegations that the sponsor that gave the team its name was a pyramid scheme. He then raced for Gan for two years before retiring from racing in 1997 and in 2005 became a sports director at the Agritubel outfit. After that team closed in 2009 he joined Bretagne-Schuller (now called Arkéa-Samsic) the following year and became the squad’s general manager in 2014.

Where does the money come from?

Arkéa, or Crédit Mutuel Arkéa to give the company its full name, is a French cooperative and mutual banking insurance group. Headquartered in Brittany, the group is made up of 30 specialised subsidiary firms, with Arkéa being one of Crédit Mutuel’s six federal branches and the second-largest federal fund within the larger Crédit Mutuel group that also owns Cofidis (Crédit Mutuel is covered in greater detail in Cofidis’ section above).

Samsic is also a Breton company, this one supplying business services. Founded in 1986, it originally specialised in industrial cleaning before becoming a more general subcontractor. Headquartered in Rennes, the company employs a total of 90,000 people with annual turnover of €2.6 billion. The founder and owner, Christian Rolleau, recently handed over the day-to-day running of the business to his son-in-law Thierry Geffroy. The brand also has a history of sponsoring the Rennes football team and Lyon’s rugby outfit.

Owners of sponsors:

Arkéa - Crédit Mutuel (FRA)

Samsic - Christian Rolleau (FRA)

Astana Qazaqstan

Who’s in charge?

Alexandr Vinokourov (49), the former rider and convicted doper, has survived multiple boardroom putsches and remains at the centre of the team after more than 15 years. Astana became involved as a backer after Vinokourov’s Liberty Seguros-Würth outfit lost sponsors in the fallout from the Operación Puerto doping scandal, in which the team was heavily implicated. Following retirement, which came a couple of years after wrestling control of the squad back from Johan Bruyneel and Lance Armstrong, Vinokorouv became manager of the team in 2013.

In 2021, the 49-year-old was briefly sacked during another power struggle between the team’s Kazakh faction and the people installed by Canadian sponsor Premier Tech before he regained control once again. Throughout Vinokourov’s tenure as both rider and manager, doping positives have persisted.

The outfit has struggled in recent seasons, with only seven WorldTour-level wins so far this decade. In 2022, the team re-branded as Astana-Qazaqstan to further forge its national identity, but the squad's highest-profile signing in years was this past offseason, when Vinokourov acquired the services of British sprinter Mark Cavendish. The money made available to sign Cavendish reflected a new-found (at least for 2023) health of the team’s financials in a departure from the uncertainty that dogged previous years.

Where does the money come from?

Samruk-Kazyna, the sovereign wealth fund of Kazakhstan, controls assets worth $94.1 billion and employs more than 300,000 people. According to the International Monetary Fund, the fund accounts for about 15% of the country’s total GDP (and the majority of its government revenue). It’s made up of a number of major companies across industries including state oil and gas firms, the state uranium company, the national rail and postal service, and airline Air Astana. This latest iteration was created in 2008 after the merger of the Samruk and Kazyna funds was ordered by then-Kazakhstan president Nursultan Nazarbayev.

The team’s reliance on the health of the nation and its economy means unrest at home disrupts the cycling team that bears the name of its capital. The 2019 Kazakh financial crisis saw the country’s exports nearly halved and the cycling team’s riders weren’t paid for the first few months of the year, leading to protests from the squad at the Giro d’Italia. In 2022, amid political unrest in Kazakhstan following a spike in fuel prices, the riders once again went unpaid for the first few months of the year, replicating a situation that had also occurred in 2021, with Vinokorouv blaming the “slow administrative processing” of government funds.

Owner of sponsor:

The government of Kazakhstan (Kazakhstan)

Bahrain-Victorious

Who’s in charge?

A Slovenian professional cyclist for a decade in the 1990s, Milan Eržen, 52, became the general manager at Adria Mobil in 2003. That team spawned from the KRKA-Telekom Slovenije that Milan rode for in the final years of his racing career.

After a decade at the helm of the Slovenian Continental team, Eržen left in 2013 to become a sports consultant for the Kingdom of Bahrain, a role that seems to have included helping Sheikh Nasser bin Hamad Al Khalifa train for an Ironman, helping develop a Bahrain triathlon team, and hosting the country’s first Ironman event.

The fourth-born son of the King of Bahrain then enlisted Eržen to fulfil his desire of starting a WorldTour cycling team and at the start of the 2017 season Bahrain-Merida lined up with star rider Vincenzo Nibali on its books.

In May 2019, Eržen was linked to the Operation Aderlass doping investigation, with the Austrian doctor at the centre of the case, Mark Schmidt, telling the court in 2020 that Eržen had “wanted to enter into a business relationship” with the doctor. Through his lawyer, Eržen denied having ever worked with Schmidt. When the link to Aderlass emerged, the UCI confirmed a number of Slovenian individuals including Eržen had been carefully monitored since 2015.

While contracted to Bahrain-Victorious, Slovenian cyclist Kristijan Koren was found to have doped as part of the Operation Aderlass investigation and subsequently banned for two years. Another Slovenian cyclist turned sports director for the team, Borut Božic, was also handed a two-year ban for his connection to the Aderlass doping ring. Both suspensions relate to doping that occurred in the early 2010s, before their time on Bahrain. At both the 2021 and 2022 Tours de France, the team were raided by police on suspicion of doping. Riders and the team maintain their innocence and at the time of writing nothing further has arisen from those searches. Eržen himself has never been charged in connection with Aderlass or been subject to sporting sanction.

Where does the money come from?

Did we do a good job with this story?