The parcel that arrived was much smaller than I’d expected, barely larger than the contents that were supposed to be held within. Surely there was some mistake, no?

On the contrary, the packaging couldn’t have been more intentional, a custom-made vessel formed with a shell of perfectly trimmed plywood sheets, small wooden standoffs around the perimeter to form a bit of a crumple zone, and just enough foam to fully coddle its precious contents, all built with exceeding care to ensure they got where they needed to go in as pristine a condition as when they departed.

A lot of time invested for something that was essentially useless, a relic of the past with almost no modern application.

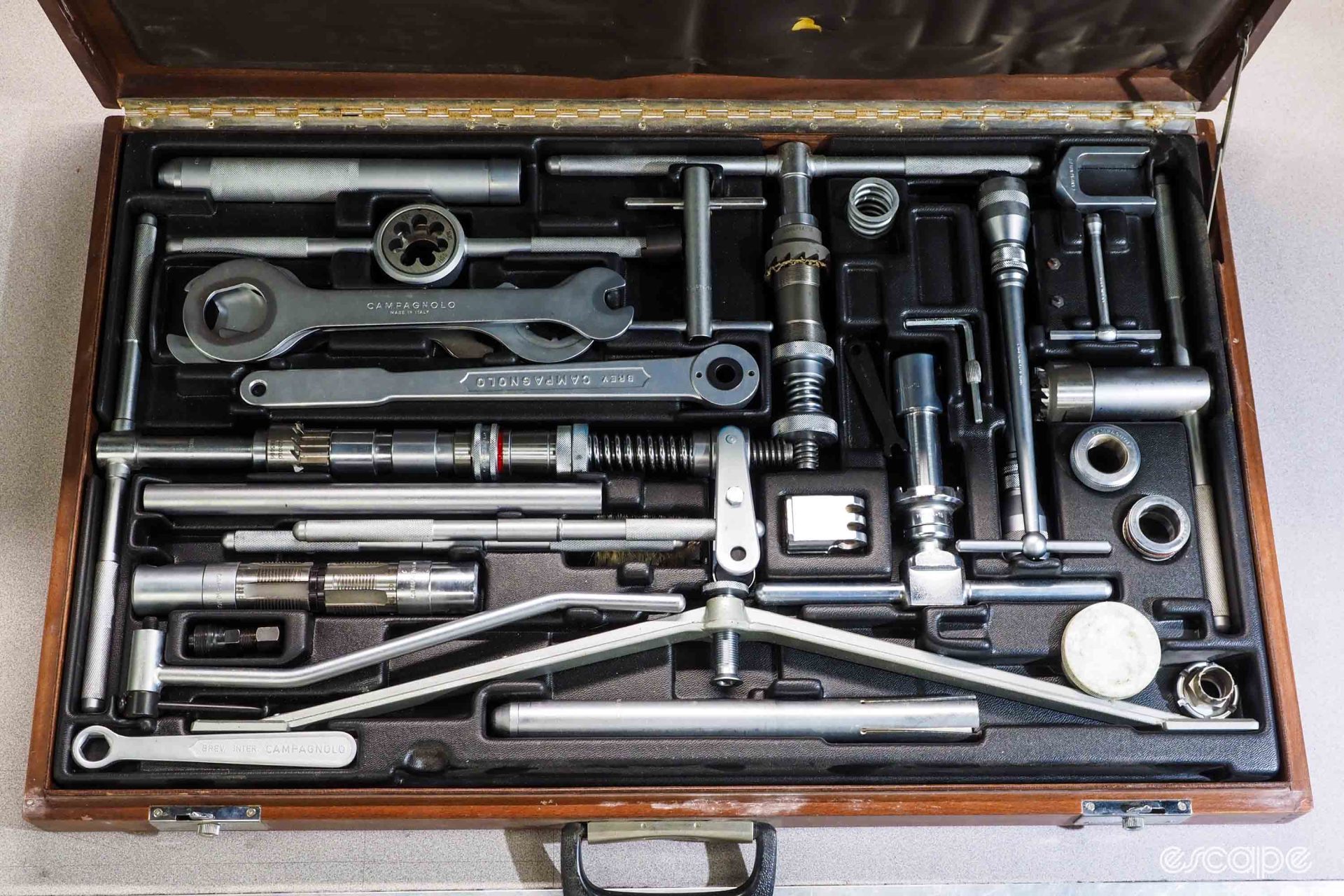

It was a Campagnolo tool kit. About 40 years old, barely used, and nearly complete. A unicorn.

Escape Collective member Bruce Judson says he bought the kit in the early 1980s. A former amateur road racer who came into the sport in the 1970s, Judson cut his teeth on the lugged and fillet-brazed steel frames that were standard-issue at the time. For a while, he aspired to become a frame builder himself, and he said the Campagnolo tool kit seemed like a wise purchase, what with its impressive array of cutting and facing tools, not to mention the vast collection of specialty tools purpose-built for the Italian brand of then-ubiquitous componentry.

“I don’t recall the store’s name, but it was in Ashland, Oregon, and a dedicated cycling tool shop,” he told me. “It’s where I purchased most of my quality tools. They were going out of business and offered a huge discount on all their remaining stock. I recall the discount being something like 50%, but I’m not sure. They had one Campy set left and I took the plunge.

“I’m an electrical engineer and wanted to build frames. My goal was to build one or two a year. I purchased a Blanchard ground steel plate, V-blocks, etc. At the time, lugs were still in, so my first few frames were built using Henry James lugs for the main triangle and fillet brazing for everything else. I built three frames before life got in the way. The Campy kit was used for surfacing the bottom bracket, etc. It rounded out my tools so that was my justification, but to be honest, it was an emotional purchase.”

No stranger to the economies of emotion, Campagnolo seemed fully aware at the time of what it had created.

“I remember the feeling of Christmas morning, or a new bike when the set arrived, but upon some contemplation it was more then that,” Judson continued. “[It was] more like a rite of passage for me. I had the basic tools, so I couldn’t really go beyond maintenance. Racing for Peugeot’s amateur team in the late 1980s, I had access to tools at the local bike shop, but the Campy tool kit was sacred and only used with permission of the ‘high priest’ – the master mechanic. The Campy tool kit opened the door to arguably anything the bike needed for build-up or repair. Facing bottom brackets, dishing wheels, derailleur alignment, etc. I probably walked a bit taller that day.”

Originally offered in the 1960s exclusively to “certified shops," the Campagnolo tool kit was a sight to behold. Ostensibly assembled in the name of practicality, it included dozens of tools that Campagnolo says were required to properly assemble and tune a road racing bike of the time. As much as mechanics lament the lack of complete preparation on high-end frames nowadays, that sort of condition was the norm back then. Frame builders would quite literally just build the frame – and likely paint it, too – but the interfaces with the components were often left raw and unfinished, with less-than-perfectly parallel tube ends and threads that were rarely as smooth as they should be.

“Times have definitely changed,” recalled Jim Potter, owner of Vecchio’s Bicicletteria in Boulder, Colorado, and a bona fide local legend and master mechanic with nearly 40 years of experience. “If one of our manufacturers send me anything I have to touch any tools, I start grumbling, like, ‘You bums didn’t finish your job.' But that’s how all frames came. You had to finish the job. You had to prep them. You had to chase them. You had to clean the slag out of the seat tube. It used to be that any frame that came in the door, first thing you did was hang the frame in the rack, get out the tool kit, and prep it. If it was a good frame, it might only take you half an hour to clean everything out – everything just runs in and runs out without making any chips. Other frames might take over an hour to do them correctly. It just depended on what the brand was and how well it was done at the factory. But that’s how it was.”

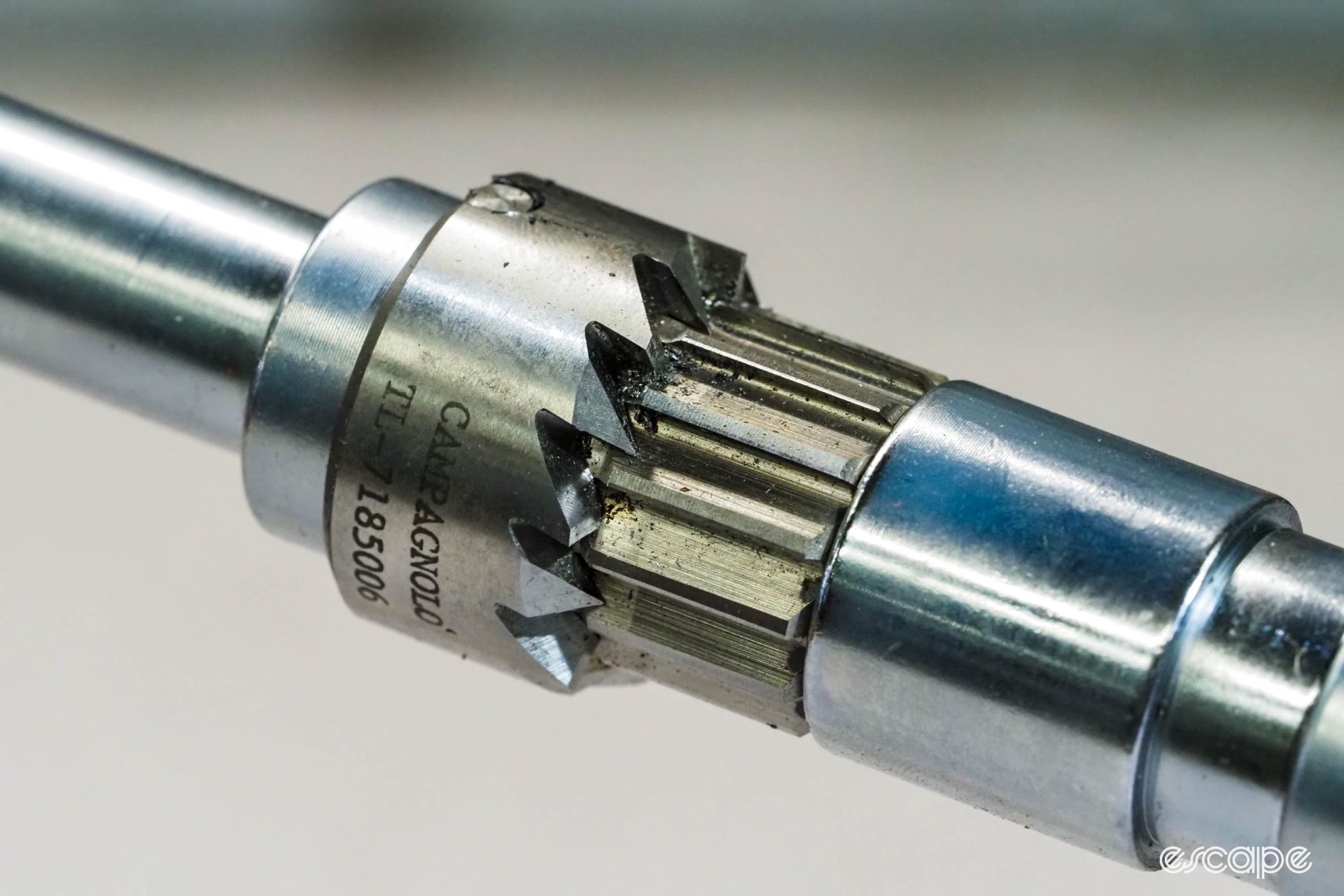

A shop certainly could have just installed components on a frame in that condition. But no good shop at the time would dream of such a thing. That Campagnolo kit included everything necessary to install Campagnolo components on a frameset, as well as nearly everything required to fully prep the frame beforehand. There were facing and chasing tools for the bottom bracket and head tube. So-called “candlesticks” to align the dropouts. Cutters to create a perfectly square seat for the headset crown race. A sturdy tool and gauge for aligning the rear derailleur hanger. A dishing tool, since all wheels at the time were hand-built from a pile of rims, hubs, and spokes. There was even a little tub of grease, since – obviously – no off-the-shelf product could do the job as well.

“The precision and functionality of Campagnolo products required a correct interface with the steel frames,” said a Campagnolo representative via their public relations agency. “Therefore, Tullio Campagnolo strongly wanted to equip all those who assembled the bikes with suitable tools. At that time and up until the 1980s, all the frames were made of steel, and although they had good technical characteristics, they lacked geometric precision due to the [manufacturing] processes which generated deformations.”

Unboxing videos may not have been a thing until the mid-2000s, but Campagnolo sure knew how to make a first impression decades prior. There was also a bit of a “shock and awe” aspect to the kit, and it was as much a showpiece as it was an object of utility.

The tools were neatly arranged in an enormous hardwood case measuring 78 x 49 x 7 cm (31 x 19 x 3”), with chromed metal latches, a full-length hinge, and a Campagnolo logo proudly embossed on the outside. Initially, the tools were even separated by wooden partitions and cradles before a (surely more economical) one-piece molded plastic bed took over in the early 1970s. All loaded up, the case weighed a substantial 21 kg (46 lb), and given such size and heft – not to mention the single hard plastic handle – it clearly wasn’t meant to be easily portable.

Rather, it was the mark of a shop that presumably knew what it was doing, of a skilled and well-trained mechanic who cared just as much about your precious new machine as you did. It was love in a wooden box.

As the saying goes, however, time waits for no one.

The Campagnolo tool kit was impressively built, but it unfortunately was crafted for a purpose that was growing increasingly narrow. Builders steadily improved the quality of their steel frames, and non-ferrous frame materials became more common. Many of the tools became obsolete as fitments changed. The beautifully cast crown race remover would only work on steel crowns – with 1”-diameter steerers, no less – and threaded headsets went the way of the dodo. Perhaps more critically, Shimano was steadily making inroads in the high-end road market, and Campagnolo didn’t exactly do a stellar job of updating the kit as the bikes it was meant to service evolved.

Campagnolo eventually saw the writing on the wall, and the last new tool kit rolled off the line in the mid-1980s.

These days, maybe you’ve heard of Campagnolo’s tool kit, but you more likely haven’t. Perhaps you’ve seen pictures of one, but never seen one in person. The likelihood you or anyone you know have had the pleasure of opening up that sturdy wooden lid in person, or better yet, have actually used any of those tools for their intended purpose? You’ve got far better luck randomly grabbing a perfectly ripe avocado at the grocery store.

Needless to say, the Campagnolo tool kit isn’t any more useful or applicable after its introduction, but yet its allure has grown almost to the point of mythology in the decades since, particularly among mechanics – both young and old – and cyclists who have been around long enough to remember when the kits were contemporary.

Perhaps as you’d expect, Campagnolo tool kits in good condition also fetch a pretty penny on the used market. They were already expensive back in the pre-Euro day at around ₤2m – several months’ salary in Italy for many at the time, and about US$4,700 today when adjusted for inflation – and it’s not unusual to see used ones in good condition selling for thousands of dollars today. Even more remarkably, you can still find them new if you know where to look – and are willing to pay the premium.

Judson said his kit mostly just “sat in the shop” after he built those three frames, partly because it was no longer as useful as it once was, but mostly because things “got put on hold as my daughter came and work got busy.”

Now, it sits in my workshop.

It takes up an inordinate proportion of my bench space, and is no more useful me than it was recently for Judson. It’s big and heavy. It’s cumbersome to move. From a logical perspective, it’s more in the way than something practical, and at some point, I’ll copy Potter’s setup at the shop for his Campagnolo tool kit and build a dedicated slide-out drawer underneath my workbench – partially so it’ll be easier to show off, but mostly so it’ll be out of the way.

Emotion is a funny thing, though, eh? Every now and then, I flick open those latches, and in my head, I hear those proverbial angels singing as I open the lid and stare at the contents for a bit. My old LeMond frame didn’t need it, but I faced and chased the bottom bracket shell just because. I couldn’t face the head tube as the original kit only included cutters for 1” frames – natch – but the bottom bracket shell cutters were an absolute joy to use. The whole process was an utter waste of time, but yet also the best use of time I could think of in that moment.

I consider myself to be an exceedingly logical person; I take after my dad like that. But my wife insists I’m driven just as much by emotion (thanks mom). The idea that an inanimate object like this Campagnolo tool kit could somehow be something more than a pile of steel, wood, and plastic makes zero sense. But in the presence of one of these tool kits, it’s hard not to romanticize being a mechanic in those days, methodically prepping a freshly built frame and painstakingly turning it into a complete bike that will soon bring a smile to someone’s face.

There’s this concept in philosophy called panpsychism. It dates back to the 16th century, and says that all things have some kind of “mind." Exactly what that means is a hotly debated topic in the field – Is it some kind of consciousness? Ingrained memories? – but the basic premise is that even seemingly inanimate objects are somehow more than just some physical bundle of atoms.

I’m no philosopher, but it’s hard not to see how that might apply here.

Does a Campagnolo tool kit make any sense these days? Nope. But does anyone care? Also no. I’m not going to go so far as to say there’s some sort of consciousness embedded here, nor do I expect to hear any of the tools speak back to me in the quiet solitude of my garage workshop.

But yet this careful arranged assortment of anachronisms is most definitely something more just than a pile of outdated tools in a wooden box.

Did we do a good job with this story?