It's been a tumultuous year for the Amy Gillett Foundation. The organisation was, for almost two decades, one of the loudest voices in the Australian cycling advocacy space; its marquee 'Metre Matters' passing distance campaign was legislated nationwide by 2021, with the organisation expanding into other advocacy initiatives, including the federally funded Safe Cycling program. So the organisation's sudden closure in February – first reported by Escape Collective – was both unexpected and troubling, as were financial documents lodged by the company's liquidator showing a deficiency of over AU$1 million, leaving employees, contractors, and even the Federal Government out of pocket.

Within a couple of months, however, there was new hope. As first reported by Escape Collective, a group of prominent Australian cycling identities – including former AGF chairmen Duncan Murray and Mark Textor, Amy's mother Mary Safe, former WorldTeam title-sponsor Michael Drapac, Australian cycling legend Phil Anderson, and former world champion cyclist, media commentator, and advocate Kate Bates – had rallied to form a proposed board that would try to revive the organisation.

By September, after navigating the financial and bureaucratic tightrope of removing the organisation from liquidation and paying its creditors, the Amy Gillett Foundation was back from the brink. The organisation's relaunch was announced with a feature article published in the Fairfax press, detailing the complex revival process and interviewing key figures about their hopes for the AGF v2.0. But what was, in many ways, a celebratory moment became a somewhat contentious one, due to the suggestion within that article that the organisation would be campaigning for mandatory rear lights for all cyclists.

Within this context, Escape Collective spoke to Kate Bates, the AGF's new general manager. In a wide-ranging discussion, Bates spoke about the organisation's focus going forward, its stance on rider visibility, and the two-way street of sharing the road.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Iain Treloar: There's two areas that I wanted to touch base with you about. Firstly, it sounds like things are all up and running again – that's really positive. I was wondering if you had any broader comments about where the Foundation hopes to go over the upcoming years.

Kate Bates: Yeah. I mean, firstly, it's immensely satisfying for everybody involved to have navigated what was an immensely complicated process. Apart from the joy of being back up and running and knowing that our work can help save lives and change the dial on road safety in Australia, it's reminded us how many people are invested in the cause and how much it means to so many people, because quite simply, we would not have gotten through the very complicated process of getting back to where we are without that support and commitment. I think that's an incredibly strong place to start, knowing that the market wants us, believe in us, and sees value in what the Foundation has achieved and can achieve.

But I think the reality is that we are now, in many ways, starting again – we’re having to really renew our focus and be very strong and focused on what it is we're trying to achieve, because it's a space that's easy to get distracted [in]. There's so many ideas, so many ways to affect change, so many things you could say are the absolute priority, but having the resources and the ability to do that is a different thing.

So for us, it's fairly simple. We have safety as our core mission, and our primary mission is to ensure that cyclists get home safely. And the way we're going to do that is by working in four main areas. The first is improving the relationship between road users, which is the overarching but almost intangible one to a degree. And then the others are separating cyclists from motorists – through law, technology and infrastructure, and in each of those buckets, there's an approach we need to chip away at it. Some things have big impact quickly. Other things will take a lot of time and patience, but we're certainly committed and prepared to do the hard yards to get there.

IT: To look at the first category – improving the relationship between road users – is that through things like behaviour change programs, or advertising? What would that look like?

KB: Yeah, I mean, we are yet to sit down and have our strategy day – that's had to come after the legalities of getting here. So I'll say that first, we haven't got the way we're doing that set in stone, but it would be fair to say that advertising and visibility – market visibility, which is important to differentiate, because cyclist visibility is another really important area – but ensuring that visibility of the organisation and of cyclists and of the issue we're trying to fix is important, and you have a couple of levers to do that. Certainly behaviour change, and you might look at something like, say, a lot of accidents occur with certain demographics of drivers. So targeted campaigns – be that advertising and also educational campaigns around those target groups, and then also using the arm of the law to change the dial a bit.

If you will indulge me while I explain this one, the Foundation did an incredible job of ensuring that in every state in Australia, the ‘Metre Matters’ passing distance legislation was passed. We now have quite a task ahead of us to ensure that that is being enforced. That will be done through advocacy with police and government, but also education for drivers – because in Australia, when you get your driver's license or when you renew your driver's license, there is no responsibility to resit a test to show that you know the updated laws, to show that you understand: you just tick a box that essentially says, “Yep, I know it all.” But we know that there's a lot of drivers – and to be honest, probably a lot of cyclists – who don't know the law to the letter, about behaviour on roads.

And that's not just about things like minimum passing distance. It's about things like behaviour at roundabouts and intersections. So there is a lot to be done in the education piece around the road rules – and there is nothing stopping us from putting a billboard up and reminding people of the passing distance legislation and the fines that are involved. And if you work that hand-in-hand with ensuring that the police regulate it more … let's be honest, that's a tough job, for police to be able to enforce that requires a real commitment from them, and that's what we'll be chasing.

But we also want to go straight to the driver and remind them that there are fines. It's about safety. The laws are there for a reason … There's a $318 fine in my state for close passing, and I'd be willing to suggest that most drivers don't know that. And so I think it's ensuring that every problem or every issue that we're trying to address and trying to solve and move the dialogue on, we do from a number of different angles. We don't just want to be behind the scenes talking to government. We also want to ensure that we have a very public-facing presence for drivers to keep conversation going, and to ensure that that relationship does improve.

IT: In the second bucket that you spoke about, you mentioned technology. There’s something that was a prominent eyebrow raiser for me, in the article in the Fairfax papers over the end of last week, where [AGF Board Member] Duncan Murray said that there's going to be a push from the foundation for mandatory flashing tail lights on bikes at all times. Is there anything that you can expand on around that?

KB: Yeah, I think we need to obviously be careful using the word mandatory anywhere. But what I would say is that we are committed to addressing the behaviour of drivers – of all road users – to ensure we're protected as much as possible, and we need the data to back that up. So we will be looking into visibility, which includes clothing as well – like socks and jerseys; the research to date says that they're the most important clothing parts – and then flashing lights as well. There's some research on that, but we are going to dive deeper into that, because if there is something that can change the game for cyclist safety, then that's a priority.

And understanding that it's a complex puzzle, understanding that drivers play an exceptionally strong role in that equation, we're also very conscious that if you're riding in low light conditions or in stormy weather or at night or on a road with a lot of winding corners, you will be in more danger if you can't be seen. It's very difficult to ask drivers to keep their distance but not consider the visibility factor. In saying that, it's not the responsibility of cyclists to ensure that drivers drive responsibly. It's just anything that will improve the safety of cyclists on our roads, I think it's incumbent upon us as a Foundation and as a cycling community to be part of that solution as well.

It's like anything: it's the minority that ruin it for the majority. And we do have cyclists who don't respect road rules, who call for the enforcement of passing legislation, but also run red lights themselves. So for us, it's very much about "give respect, get respect", and we will be working tirelessly on sharing the road and relationships with drivers and all of the factors that can lead to that. And in technology, we're also talking about cars and what safety technology features in cars can be a game-changer – from indicators to prevent dooring to heads-up displays in cars that mean you don't have to look down at the dashboard even for a microsecond.

That all has a huge amount of interplay, but we do have a responsibility as road users ourselves to ensure that we're visible, and I don't want more emphasis put on that than on the other things that we find important. And I think you know – you’re media, you know how it works. Sometimes something gets grabbed and run with, to the exclusion of some of the other things that have been said. But visibility is certainly very important for us, as is the interplay of how our roads are shared.

IT: I think that there's obviously merit in looking at how cyclists can do more to be visible – whether that’s daytime running lights or making choices with your clothing. To me, that’s more common sense, though. To clarify, is mandatory rear lights the position of the Amy Gillett Foundation? Is this something that Duncan said that was a little bit ahead of himself, or is that something that you're going to be actively campaigning for?

KB: Duncan's a brilliant man. I'm going to say that we are looking into the research behind that. If there is enough research and clear research to say that that would be a gamechanger, then that may be something that we push for. In the meantime, from a common sense perspective, we're certainly encouraging everybody to make choices around visibility that follow common sense: "Be safe, be seen".

Research from the organisation is going to be important to continue to look at the different ways that we can make cycling safe in Australia, and if the research backs it up, [mandatory rear lights] may be something that we push for, but at this stage, it's just a strong area of research and interest for us to ensure that we have an understanding around rider visibility and the safety impacts of that.

IT: OK, fair enough. I think that one of the things that raised my eyebrows about that was that there is stuff that seems like it should be common sense – I use rear lights on my bikes, and that's a choice that I've made. But I'm also interested in where this could lead.

If you're talking about technology – and as technology develops, we could be looking at things like transponders, which alert cars to positions of riders on the road and all that kind of stuff – at a point, the financial responsibility of those purchases and therefore the rider's safety is on the rider, but as riders we are the victims, the vast majority of the time, in any car-versus-bike collisions. So there's something to this stance that feels almost victim-blamey. Does that make sense?

KB: Yeah, and a couple of things on that … The first thing is, I understand where you come to the [phrase] "victim-blaming", and I'll say that I'm pretty sensitive to that phrase. As a female in Australia, when there's so much discussion around domestic violence and in that area where women are told to change their behaviour to minimise their risk – I want to go to ends to point out how different it is when we're advocating for cyclists to be more visible.

In the interplay with cycling and visibility – in the middle sits a real flair for fashion in the cycling world, and a lot of that fashion is black lycra and black bikes, black socks. If you are going for a ride in the rain, the vast majority of people will wear a black rain jacket with black socks, because they don't want to ruin their white socks. And they don't buy another colour rain jacket because most of them are black on the market, and because, again, with mud and dirt, you don't want to ruin the jacket.

I get it. But there is also no arguing that if you are in all black in low light conditions, and a car comes around the corner on the Great Ocean Road, it's very difficult to see you. That is a very different scenario to a car who sees you and doesn't pass with enough distance, or a car who should have seen you but was distracted, or a car who jets out of an intersection without stopping and properly looking over their shoulder.

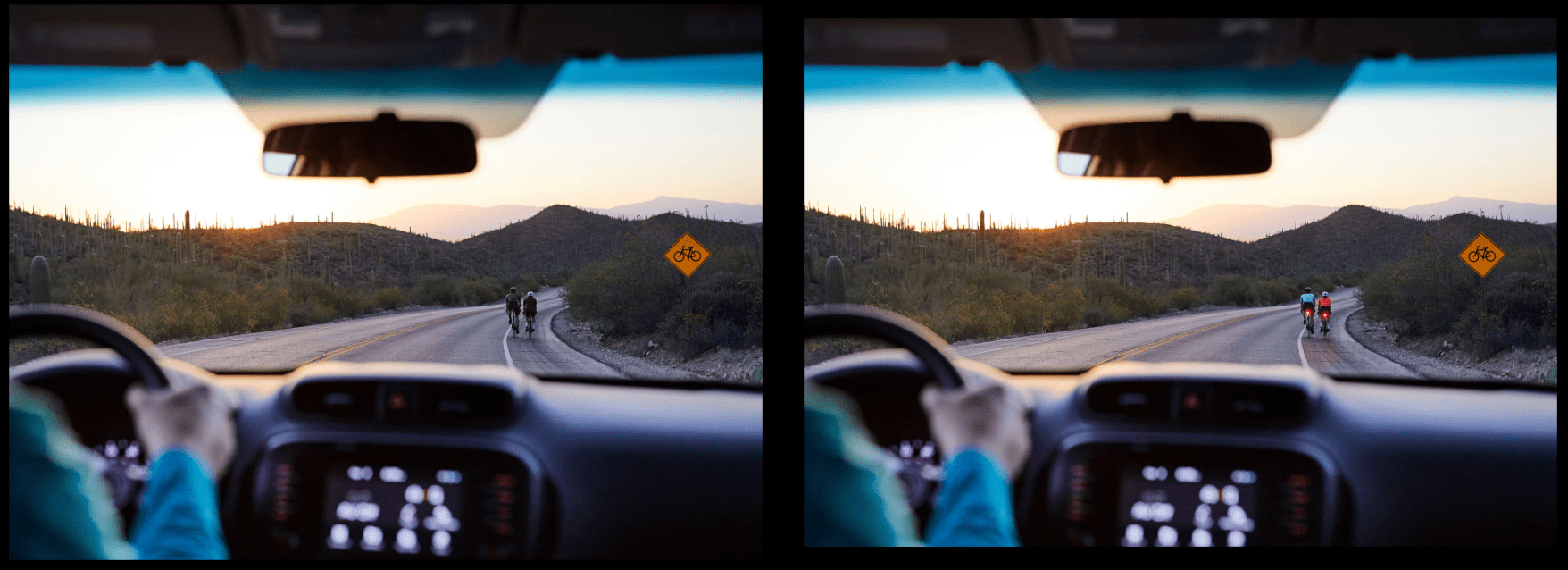

So it is a nuance, but it's a very big difference. There’s a lot going on in fabric technology – so that instead of convincing people not to wear black, we can create garments that are black but visible, black and reflective. The Foundation did a great project with Santini last year, and you may have seen some advertising around the Amy Gillett pink jersey [ed: pictured in the feature image up top]. Yep, it happens to be pink, so it's pretty visible anyway. But the important part of it is the fabric technology, where it's reflective, and so in low light conditions, you look like a disco ball. Now, the jersey could have been black, and the same would remain true, that it's exceptionally visible. When you have so many cyclists on the road where there is that interplay around kind of fashion and expensive clothing, I guess we want to be able to encourage the use of technology to let people enjoy their fashion, wear what they want.

All of these clothing brands can really thrive, but also to have really standard technology in their garments. It’s like you see in cars now – when it first came out Apple CarPlay may have been a bit of a bonus, but now it's just in every car. That’s what we want with clothing and technology, and visibility in general. Kind of talking to the victim-blaming aspect – which, by the way, I understand why you come to that term, and that's why I felt that it was important to really differentiate it.

IT: I apologise if that was a triggering term to use ...

KB: Oh no, not at all. I mean, it is certainly something that in our society we have to be very, very cautious of because in regard to ever keeping somebody safe a lot of the time, whatever's the easiest way to do that is the easiest way to do that, right? That makes sense, but it doesn't actually solve the problem. So we need to solve the problem. That's what we need to do.

So when it comes to lights, I understand with regards to cost, and then I think that's where there's an interplay with bike distributors. You might remember that there has to be reflectors on bikes when you buy them, then people just take them off. So I think to a degree you kind of lose the cost argument – because if the Australian Standard requires a flashing light, then that's what it requires. And so it would be for us, if the research really supports that that would make a significant difference, then our job is to advocate for that to become standard, to take the onus and the burden off the consumers and just make sure that it's a standard inclusion, as are reflectors.

Because I think we can also all agree that when you’re talking about bike riders who love their gear, love their equipment, and are very proud of it, you're not going to get any compliance if you said you have to keep the reflectors on your wheels – that's a nightmare. But flashing lights almost seems like a compromise in the middle of what everybody can very easily do.

So, good question. And I think that's where the word 'mandatory' is premature – but we're advocating for everybody, if you have access to lights, to make that something that you consider.

IT: I know Amy Gillett Foundation has historically been quite road cyclist-focused – and when you're talking about things like clothing brands and fashion and technology and black bikes, that all checks out for that road rider demographic. But if I'm thinking of a transport cyclist or a recreational cyclist who is just trying to have as few obstacles to bike riding as possible, to just get them out ... we're talking here about probably a $600 outfit and a new rear light, and that feels like a deterrent.

In the policy space that you're working on, is there a distinct focus on road riders, or are you looking at people from all across the socio-economic spectrum – from people that ride bikes to people that identify as cyclists?

KB: Yeah, we're certainly looking more broadly. You're right, this is expensive gear, and there's a lot of our demographic and a lot of cyclists who need to be protected that aren't racing road cyclists or MAMILs or what have you. But the research into the fabric technology, into visibility, gives an understanding that can then be applied across the board.

And to be honest, I think that the onus really needs to also be shared by clothing manufacturers who do any sport clothing. [Australian sporting goods store] Rebel Sport should have T-shirts that have this kind of fabric technology in it with reflective ability, to be safe to be seen. There needs to be a lot more focus from innovators and entrepreneurs around products and visibility that isn't just another high-vis vest. There's absolutely no reason why companies can't start incorporating safety features into design, and I think, frankly, they need to up their game. Whether you're talking about commuting to work, or whether you're talking about hiking, going for a run, walking home at night from the train station with a backpack on … there's so many scenarios where safety would be improved by visibility. It's not just cycling.

And so I think that we really need to put more social responsibility back on the designers and the manufacturers, because it shouldn't just be high-end stuff. It should be T-shirts, normal pants. It should be things that people can wear at any point and also happen to ride a bike in.

IT: In terms of the relationship between bike riders and drivers, who are overwhelmingly the risk factor for those bike riders – we've already got mandatory helmet laws, and now we’re talking about advising riders to have lights on and to wear such and such clothing and all this kind of stuff to enhance the rider's visibility. On the flip side of that, how does a driver not look at the riders that aren't doing those things and think that they brought it on themselves, or for police that are assessing an incident to go, 'OK, well, you were wearing black, so therefore you’ve contributed to this and we're not going to prosecute the driver,' even though legally it may be entirely their fault?

KB: Yeah, good question. I think that there needs to be a lot more focus put on the policing of any incidents, ensuring that there's appropriate punishment and appropriate investigation. I think that when you have the research and the data, then that is a gamechanger. I guess you could also ask – if you're wearing all black, low light conditions, you don't have a light on, is it legitimate for a driver to not see you? And that is a very difficult question based on very specific circumstances, but I think there needs to be awareness on all sides so that you can make your own choice. If you know that lower visibility increases risk, then to a degree, you're making that choice, and people have the autonomy to make many choices.

What we want to do is come out with hard facts. Because conversely, if we do some research into this, and it says, “You know what, it doesn't really make a movable difference …” So far, the data hasn't said that. So far, the data says this will increase rider safety and lessen collisions. But if the evidence said it won't really make a movable difference – well then, that's also important information for police, for prosecutions, for any kind of behavioural change. And for any driver that says, “Oh, I didn't see them,” then there is no real reason why they didn’t if they weren't distracted. So it kind of cuts both ways.

IT: I guess, but I do still think that it pushes the onus on the rider for their own safety …

KB: I do too, but I also think that we shouldn't shy away from taking some responsibility ourselves, because we can't look at it in a vacuum. You can't say riders are having to take responsibility and not cars. We are working tirelessly as well to change driver behaviour, but it's a piece of the puzzle. You know, there's a very multifaceted approach that we have to take. In the same way that we're not going to ignore the horrendous driver behaviour, we shouldn't ignore anything else that can markedly and measurably positively impact the safety of people on roads.

IT: Thank you for the chat. Is there anything that you wish that I'd touched on that I didn't, or that you'd like to add?

KB: I think they're really good questions, and I think people are asking and interested. I just want to reiterate that in terms of anybody ever suggesting – and it has been suggested on social media that we may be victim-blaming – we are a Foundation set up in honour of somebody that we lost and we still grieve, and we are not blaming victims at all.

We are trying to make sure everybody gets home safely, and we are making sure that respect on the roads – that sharing the roads is a responsibility that everybody agrees is there – and to improve that relationship. That's about the top line of it.

Did we do a good job with this story?