In pro cycling, every new trend, whether a technological breakthrough or a training technique, follows a predictable trajectory. First, it's dismissed or laughed off, then quietly embraced by a minority, and finally, it achieves mass adoption when one of that minority wins a big race with it. Science can say whatever, but ultimately, everyone just wants what the winner uses.

So-called "shorter cranks" have now completed this cycle. While the trend was first popularised in triathlon, the pro peloton largely ignored anything shorter than 170 mm crankarms for years. That reluctance was slowly fading, but then … 2024 Tadej Pogačar happened.

Pogačar rode with 165 mm cranks in one of the most dominant seasons ever, and whether they made a difference or not, it had many riders around the world questioning if shorter cranks might make them faster too.

While some riders had already adopted shorter cranks – including early adopter Lizzie Deignan, who turned to 165 mm cranks back in 2020 to overcome a persistent hip issue – if one thing is clear from the opening days of 2025, it's that shorter cranks are sweeping through the men's peloton.

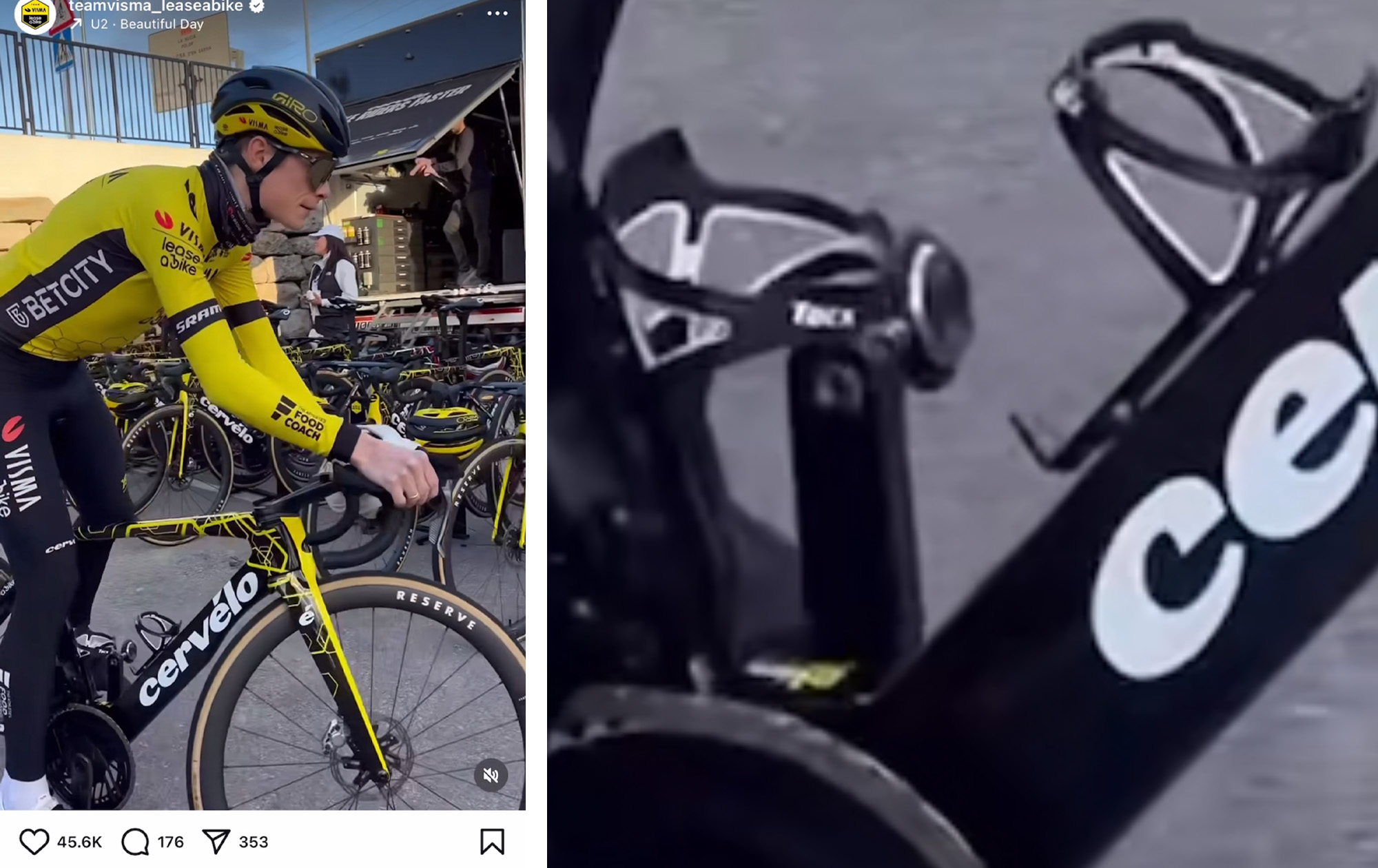

This is most obvious at Visma-Lease a Bike, where short cranks are literally everywhere; a substantial number of the team's male riders, including its biggest stars, are now on 165 and even 160 mm crankarms.

Team equipment supplier SRAM would only confirm it has seen a trend towards shorter cranks. Visma-Lease a Bike's press officer said in a response to a request for comment that crank length differs from rider to rider and the shorter-arm trend is not completely new, but acknowledged that it is increasingly common. When asked about what seems to be a big change at Visma over the winter, he said only that "Innovation has always been an important part of our team. And this is just part of that; some riders with shorter cranks." Whatever the extent of the change, what does seem clear is that what was once considered short is now the new norm.

One crank to rule them all?

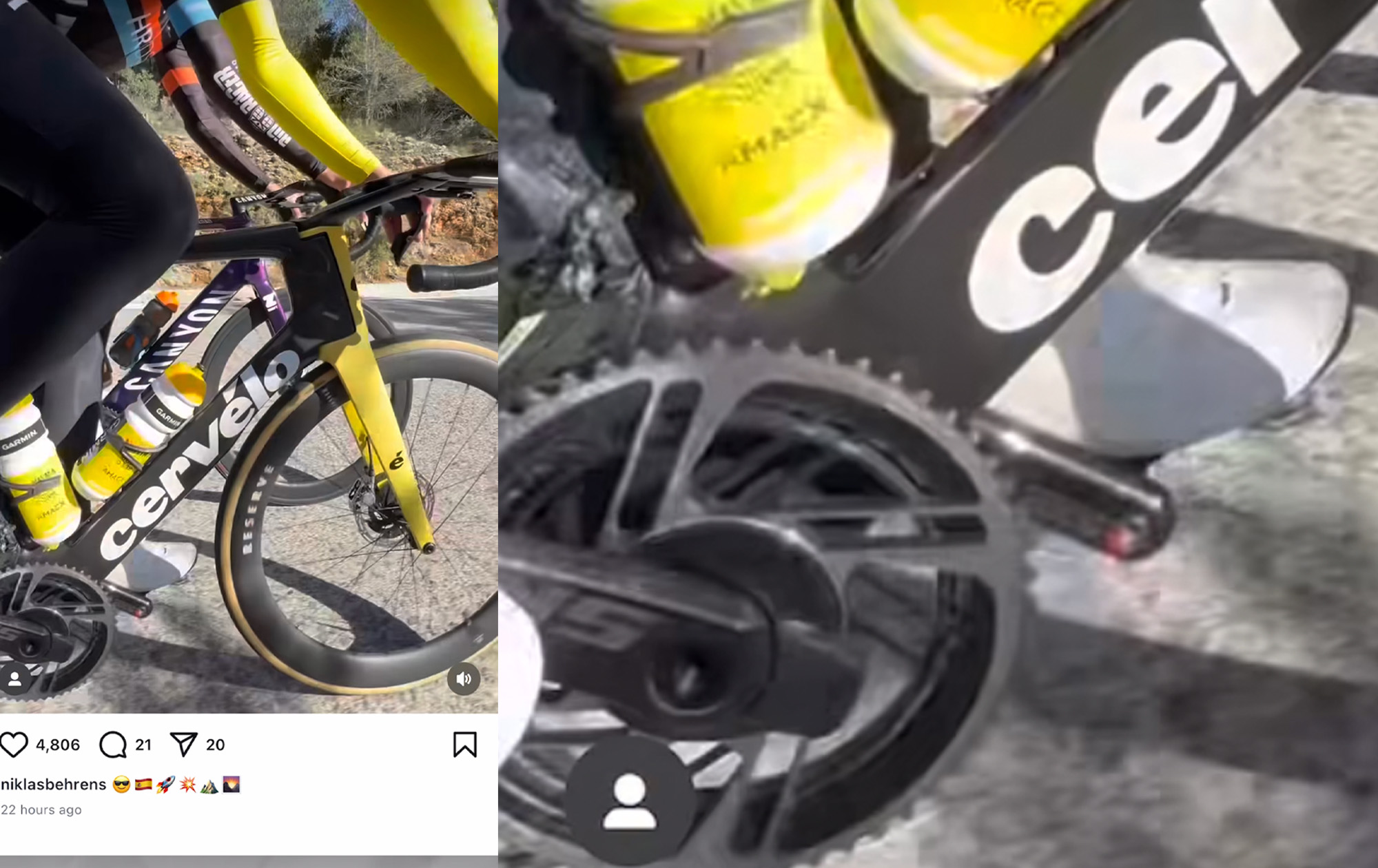

SRAM crankarm length is easily identifiable thanks to a colour-coded stripe system it uses on the inside face of its cranks at the pedal axle. A yellow stripe indicates 175 mm, green signifies 172.5 mm, purple means 170 mm, pink is 167.5 mm, red represents 165 mm, and blue denotes 160 mm. (SRAM, like many component brands, does not make a 162.5 mm option.)

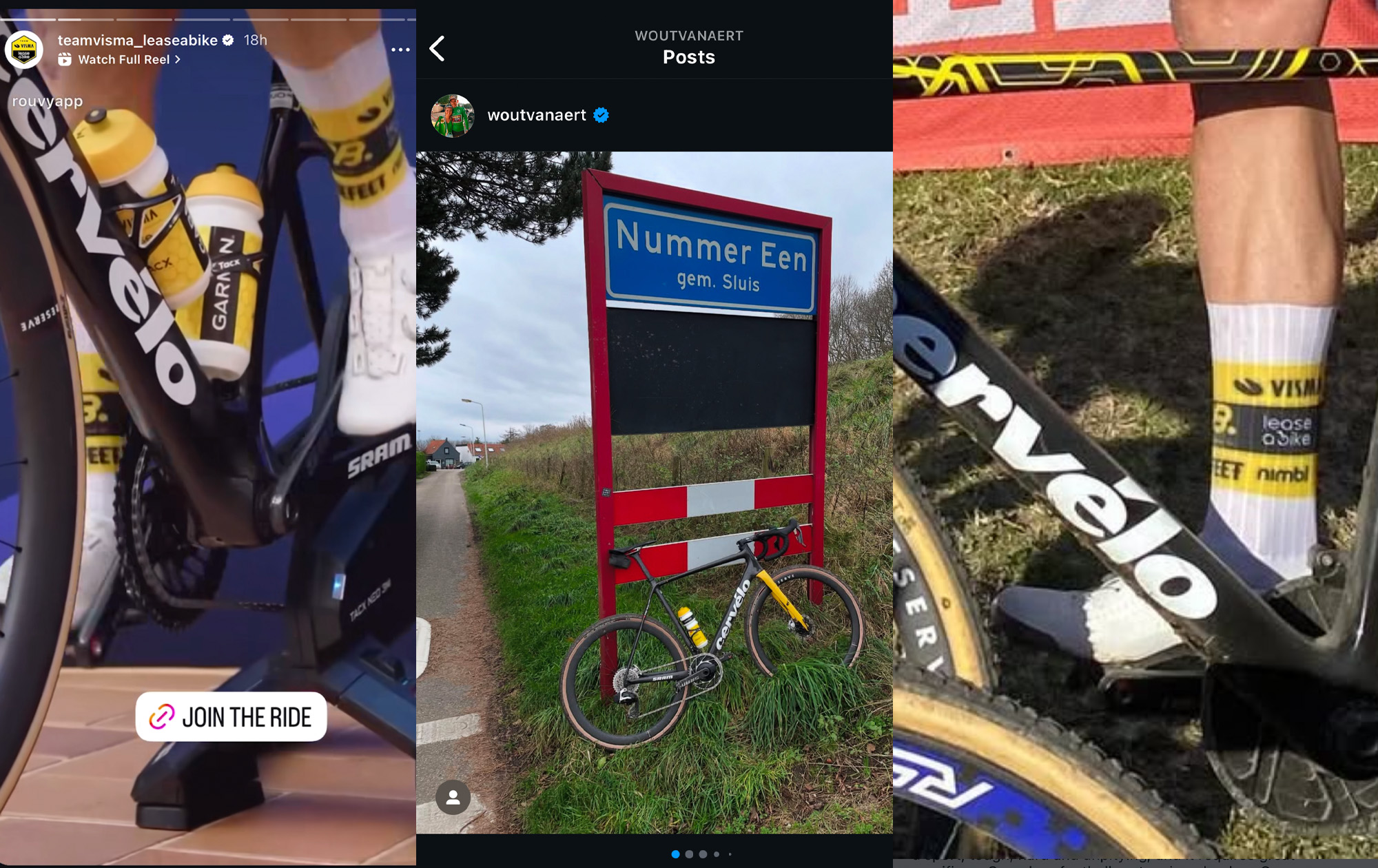

After scouring race photos and Instagram reels, we've spotted numerous Visma riders of varying heights using red-striped 165 mm cranks and several more using the blue-striped 160s. There's also perhaps a new crank length from SRAM in use, with some riders, Wout van Aert and Jonas Vingegaard included, spotting riding cranks without any evident coloured stripe.

Speaking of star names, Van Aert (190 cm/6'3") has been spotted training on red-striped 165 mm crankarms, much shorter than a rider of his height would have traditionally used. Similarly tall riders like Dylan van Baarle (187 cm/6'2"), and Niklas Behrens (195 cm/6'5") have also been spotted training or racing on 165 mm cranks.

Instagram photos also show that Van Aert's cyclocross and road bikes are both equipped with red-striped (165 mm) cranks, all but confirming a shift away from the 172.5 mm cranks he previously raced with. And while an article on Velo about his time trial setup didn't mention crank length, the red-striped cranks are also clearly visible on his TT rig.

Visma's adoption of shorter cranks tracks broadly but not exactly to rider height. Loe van Belle (184 cm/6'0"), Menno Huising (185 cm/6'.5"), and Matthew Brennan (height not listed) are all racing 165 mm crankarms at the Tour Down Under, the same as the taller Behrens and Van Aert. Meanwhile, rookie Tijmen Graat (176 cm/5'9") has taken things a step further, racing with 160 mm cranks.

While we haven't yet seen all the 2025 Visma bikes, one thing is clear: The team has embraced shorter crank lengths across much of its roster. In fact, of the team bikes we have seen so far, I couldn't find a single Visma rider using anything longer than 165 mm.

Mystery cranks

That said, some of the Visma bikes spotted at the team's training camp appear to lack a color-coded stripe entirely – at least that we could identify from an Instagram screenshot. They could be the blue-labeled 160 mm cranks (with the stripe just not evident due to lighting or photo file size). Or perhaps they're black, and SRAM is using that color to denote a new length like 162.5 mm? Or are they simply unlabelled cranks, length unknown?

Interestingly, these unidentified cranks were spotted on Vingegaard's bike during a January training ride and, similarly, on Van Aert's bike back in December before his bikes were seen with the clearly red-labelled cranks mentioned above.

These sans-label cranks could simply be "standard length" cranks produced specifically for the team without a label, perhaps as part of the pro-only decals SRAM applies to its sponsored-rider equipment. However, that doesn't quite explain why SRAM has remained tight-lipped, declining to comment on what these black or unlabelled cranks actually are, or why only some of Visma's bikes feature them.

A broader trend

At the 2025 TDU, Escape Collective's Dave Rome has observed a clear shift towards shorter cranks across the men's pro peloton, noting that even exceptionally tall riders are now embracing them. Rome reported that 170 mm cranks are becoming the new normal, while he also spotted a significant number of 165 mm and even some 167.5 mm cranks in the pits.

Groupama-FDJ's Head of Technical Development, Jérémy Roy, confirmed to Escape that many of the team's riders now opt for shorter cranks following an off-season analysis conducted in response to the growing trend of more forward riding positions.

According to Roy, the increasing shift towards more forward-biased rider positions, often seen in both time trials and road racing these days, has prompted the team to rethink crank length choices.

Groupama-FDJ's bike supplier, Wilier, acknowledged the growing trend towards sub-170 mm cranks and hinted that shorter options could become part of their stock offerings in the future. When asked whether demand was strong enough to warrant such a change, Wilier indicated that their "à la carte" ordering system, made possible by their in-house assembly line, theoretically allows riders to spec shorter cranks if desired.

However, other brands are already showing the first signs of change on consumer bikes. Trek varies crankarm length according to frame size across much of its road and gravel line, with small and extra small bikes equipped with 165 mm arms up to 175 mm arms on the largest sizes. Factor Bikes will start downsizing the stock crank length, starting with the smallest bikes, which will get much shorter cranks. And since the trend started in triathlon, it's perhaps still led by that market, as Cervelo is already stocking 165 mm cranks on even its larger P5 TT bikes.

With more teams and manufacturers adapting to the trend, it's clear that shorter cranks are no longer just an experiment; they're now in demand across all levels of the sport. The question is whether brands will need to move even further; Trek may need to offer shorter than 165 mm arms on its smallest sizes, and Giant – which does size-specific arms on its TCR and Defy lines – will almost certainly need to come down from its minimum length of 170 mm on size XS frames.

Interestingly, though, despite the early-adopting Deignan achieving so much success since her switch to 165 mm cranks, the trend is seemingly not as common in the women's peloton at the Tour Down Under. In fact, on the women's side, it was the opposite of the height-to-crank length ratio that surprised Rome on the men's side, with many shorter riders still using 170 mm cranks.

Manufacturers didn't respond to Escape Collective's requests for comment, but it is possible that this status quo on the women's side could be explained by a surge in demand for cranks shorter than 170 mm on the men's side.

This surge has been so rapid that manufacturers are struggling to keep up. While neither SRAM nor Shimano provided official comments, an industry source told Escape Collective that SRAM's 160 mm and 165 mm cranks are now in short supply. A quick check of stock at some wholesale distributors reveals that these sizes are sold out until at least March, with some unavailable until June.

Shimano is also experiencing high demand for its 165 mm cranks. A contact from one men's WorldTour team indicated that 165 mm and 170 mm cranks are now requested as frequently as the long-running standard of 172.5 mm, while 175 mm cranks are becoming increasingly rare, with only a few riders across the entire team still using them.

With all this change, one thing is clear: shorter cranks are now widely accepted and no longer dismissed as silly. But the more significant questions remain: why the sudden shift, and are shorter cranks truly the performance panacea they're made out to be?

Why Shorter Cranks?

Shorter cranks offer several potential benefits across different aspects of cycling performance. We explored the pros and cons of shorter cranks and why they aren't for everyone in a recent episode of the Performance Process podcast, so here we'll briefly outline the proposed benefits:

- Biomechanics: Shorter cranks reduce the overall circumference of the pedal stroke and the height difference between the top and bottom dead centre positions. This reduction in movement range helps minimise the range of motion required at the knee and hip, potentially enhancing comfort and lowering the risk of impingement, particularly in aggressive positions such as time trials.

- Aerodynamic Gains: While shorter cranks aren't inherently more aerodynamic (there's a negligible reduction in frontal area), they can open up the hip angle at the top of the pedal stroke. This improved hip clearance may aid riders in sustaining a lower, more aerodynamic position for longer without compromising power output or comfort.

- Proportionality: Shorter cranks may provide a more proportionate fit for smaller riders.

- Rock Clearance: In off-road disciplines, shorter cranks reduce the risk of pedal strikes on technical terrain, offering improved handling and confidence.

One commonly cited reason shorter cranks haven't gained widespread adoption until now is the belief that they reduce the leverage or torque available per pedal stroke. While it's true that shorter cranks reduce the effective lever arm, it's important to remember that this lever arm is just one component of the larger mechanical system of the bike and rider.

In practical terms, any potential loss of leverage from a shorter crank is easily compensated for by adjusting the gear ratio. This is typically achieved by simply shifting to a smaller chainring or a larger rear sprocket, but it could also mean simply changing the chainring or sprocket combination used.

In essence, gearing compensates for leverage, meaning a shorter crank does not inherently reduce a rider’s ability to generate power or speed, except in scenarios where the available gear ratios are insufficient (you've run out of gears) to match the rider’s preferred cadence and torque output.

However, one more potential advantage could make Visma's widespread adoption of shorter cranks even more seismic: if the UCI introduces gear restrictions, which have been making headlines recently.

Unintended marginal gains?

If the UCI were to impose a limit on maximum gear/chainring sizes, there could be an advantage to any team that had already switched its entire squad to shorter cranks. How so? It all comes down to foot speed.

As mentioned earlier, shorter cranks reduce the overall circumference of the pedal stroke, meaning the rider's feet travel a shorter distance per revolution compared to longer cranks. This results in lower foot speed at the same cadence (RPM), as the feet cover less distance around the pedal circle.

Should the UCI introduce a gearing restriction, the ability to maintain higher cadences efficiently could be key to achieving higher speeds on steep, straight descents. A rider with shorter cranks and lower foot speed may sustain a higher cadence more comfortably, which means they reach higher speeds before "spinning out" (reaching their maximum sustainable cadence).

In contrast, riders with longer cranks (experiencing greater foot speed) may not sustain the high cadences as efficiently, leading to earlier fatigue and limiting their maximum speed within the gearing constraints in this specific straight and steep descent scenario.

Thus, shorter cranks could help riders reach and sustain higher cadences more efficiently, effectively allowing them to achieve higher speeds before feeling the effects of spinning out. It's marginal at best, but another reminder of the unintended consequences, loopholes, and work around that often arise from rule changes.

So are shorter cranks right for you?

The jury is still out, but its verdict will almost certainly be: "It depends."

While shorter cranks may help some riders comfortably adopt more aero positions or sustain higher cadences, despite Visma's seemingly team-wide switch, there is unlikely to be a one-size-fits-all solution.

Bike fit, body dimensions, and riding style all play crucial roles in determining whether shorter cranks are worth the investment.

In that same episode of the Performance Process podcast, bike fitter Jan Neuhaus and Nick from Wove Saddles shared their insights on the trend towards shorter cranks and the broader implications for bike fit and performance.

Neuhaus, a bike fitter with Gebiomized and a bike fitting trainer with the International School of Cycling Optimisation, spoke of his experience working with professional cyclists. He highlighted that crank length should be considered as part of a holistic bike fit, rather than an isolated change.

Neuhaus noted an increasing interest in shorter cranks among road cyclists but cautioned against blindly following trends without considering individual biomechanics and riding goals.

He explained how pressure mapping and motion analysis can help identify whether a crank length change is beneficial, citing common signs such as excessive pelvic movement and instability when cranks are too long.

However, he emphasised that shorter cranks aren't silver bullets and that other elements like saddle shape, cleat placement, and front-end setup must be evaluated first.

Nick from Wove is also a seasoned bike fitter and challenged the idea that shorter cranks are a universal solution. He emphasised the importance of looking at crank length in the context of the entire fit process, proposing a three-step approach to bike fit:

- Rider position relative to the bottom bracket – Establishing an optimal saddle fore-aft position before adjusting crank length.

- Crank length for biomechanical efficiency – Selecting a length that balances quad and glute activation to maximise power application.

- Handlebar height for hip angle – Adjusting the handlebar height to open the hip angle.

Nick pointed out that crank length should not be used solely to open the hip angle, as, in his experience, there are better ways to achieve that, such as adjusting saddle position and handlebar height.

The trend will continue to evolve

While the widespread adoption of shorter cranks shows no signs of slowing down, it's important to remember that they are not a one-size-fits-all solution to bike fit or performance optimisation. Simply swapping to 160 or 165 mm cranks does not guarantee improved comfort or efficiency.

That said, the same caution applies to the traditional 170-175 mm cranks that cyclists have used for years. There's no universal rule that these standard lengths are inherently better or more suitable for every rider. Every rider is unique, and identifying the right crank length should form part of a detailed and holistic bike fit.

What the shorter-cranks trend of 2025 does represent, however, is a fascinating shift in how cycling teams and bike fitters approach performance optimisation. Visma's broad adoption of shorter cranks is one of the most significant technological shifts in recent pro cycling history. While many teams claim to let data drive decisions rather than tradition, few changes have been as rapid or potentially groundbreaking as this departure from the long-accepted norm.

It's unlikely that Visma's wholesale switch was purely a reaction to Pogačar's 2024 winning formula. However, if history has taught us anything, it's that success drives adoption. Visma's bold move will almost certainly set the stage for a broader shift across the peloton in the very near future, regardless of whether it is right or wrong.

Did we do a good job with this story?