You’d think that by now, they’d be tired. Knackered. Dead. Or at least fed up with working so hard, particularly working so hard to bring back a break of four pesky riders. But those four pesky riders are Victor Campenaerts and Pascal Eenkhoorn of Lotto-Dstny, Kasper Asgreen of Soudal Quick-Step, and Jonas Abrahamsen of Uno-X, each what we in the business call “a big engine.” They are like the Energizer bunnies of cycling – they keep going and going and going … riding with metronomic dedication. Cooperating.

Meanwhile, Jasper Philipsen and his Alpecin-Deceuninck team are not satisfied with just the green jersey, with no fewer than four stage wins. They want more. Badly. And for everyone else, they want something, too, especially those teams who are running out of days to try. I get to the finish with 12 kilometers to go. So far, the break is holding out, but surely they can’t hold out against all that self-interest. It’s salivatingly close and no one, it appears, is having fun.

At first, I thought the slight lumpiness and the last few days of sheer exhaustion would be enough to deter the men from seeking a bunch sprint. The green jersey is no longer an open race. But when I asked resident breakaway expert Matej Mohorič this morning if he expected a sprint, he said yes, and that Alpecin were the clear favorites, but that the stage was open to a “surprise.” And yet, the motivation is there. In Mohorič’s words: “The difference is when you go on the attack, then you can focus in a different way and you have more determination to actually do something. And the ones who are trying to get back to the front of the race have a harder task. I think this is why it’s very likely in the third week that the breakaway is gonna survive.” As the kilometers dwindle and the break lingers on, I think about what he’s said.

The final kilometers of a sprint is like a big party for everyone but the riders. When we rode through in the car, the noise from the barriers was loud, but surely when the men come through it’s deafening. Everyone was drinking and having a blast, the atmosphere is joy – but the road also narrows, goes around corners, and you feel the vulnerability of the closeness of the barriers, to which they get nearer and nearer, peloton and breakaway, attached by a fragile string of time. Twenty-three seconds with less than 10 km to race.

Something interesting begins to happen. Alpecin starts to look a little wan after all that driving. Søren Kragh Andersen pulls off. No one immediately comes to replace him. There’s a sense of confusion. Who’s next in the hierarchy. Jayco-AlUla starts to make a move, so does Intermarché-Circus-Wanty but there’s still hesitation. There is a shift in effort. You can see the gears turning – the Machiavellian play unfolding. Calculations are at work. The gap is 22 now. Seven kilometers, and now crosswinds.

The battle of leadouts in the final few kilometers of a sprint stage is a social game, a game of cohesion. It barters with time, and usually wins out. Everyone is wary of everyone else, and yet the closer to the end they get, the more they need rivals to keep things in check if the expected team isn’t able to or doesn’t want to. Burn everyone, though, and there is no one else to execute the sprint. Lidl-Trek and Quick-Step are shredded. Mattias Skjelmose brings it back to 12 seconds. A massive turn. Then it’s Bora’s Nils Politt, another great big pull.

Behind, no one wants to spend the men that matter. There’s a sense of powerlessness, a scramble, they’re running out of road extremely quickly. They have the breakaway in their sight. Two kilometers. Surely, it will end like expected. It looks over, though no one wants to be right when they say that. All of us standing around the Jumbo-Visma bus watch on television in great suspense. But the thing about the breakaway is that the men in it are committed. They aren’t messing around. And they are strong – it is a group of diesels, a particular type of rider that powers men like Philipsen into where they need to be.

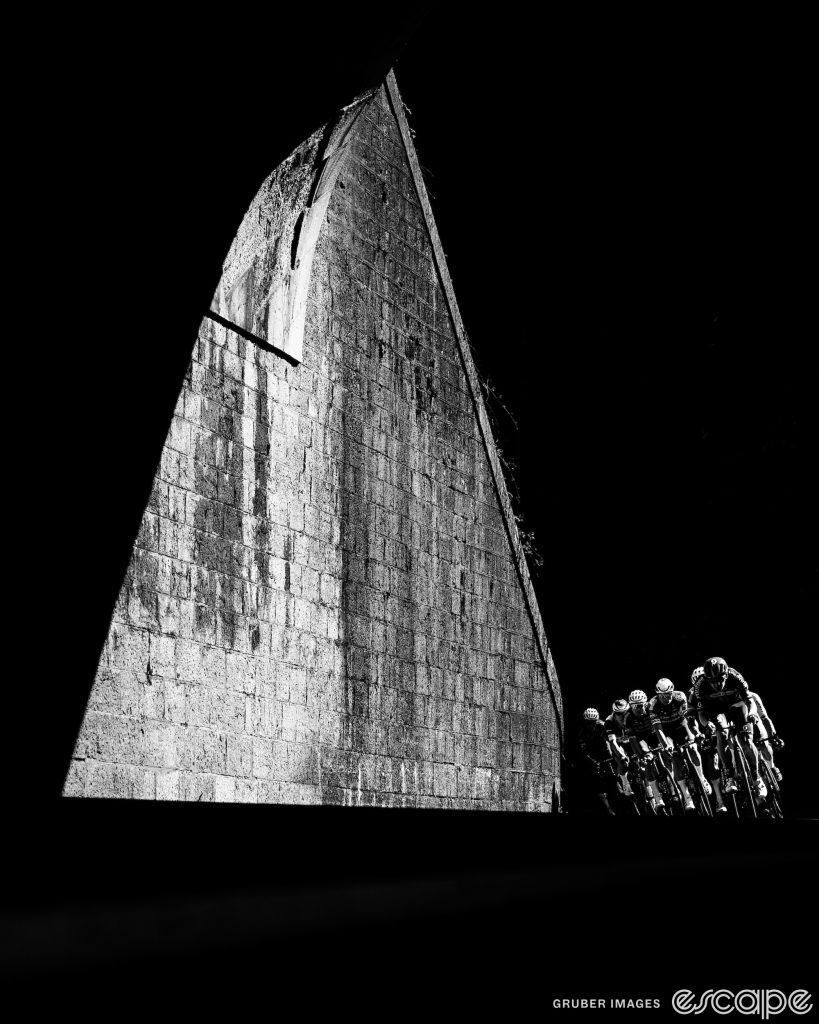

One kilometer. There is a small slowing in the front and everyone shouts, no, no, no, don’t do it, don’t mess around. The bunch surges behind, a hulking mass, a wave about to crash down upon the four out front, who seem as small as a pack of minnows.

Time stretches out in moments like this. Journalists have already started running to the Alpecin bus, expecting a sure catch. Children waiting for autographs clutch their caps. Everyone’s eyes widens as the space between defeat and victory narrows, narrows, narrows … the quartet start their sprint in the smallest space available to them, what seems like less than fifty meters, not even time for a real wind-up in power, more than a leap. They surge across the road. The two Lotto riders try to help each other out. Abrahamson, working alone, launches to one side, Asgreen alongside him, the peloton only a few bike lengths behind. In the space of a single moment, one man flashes across the finish line first, arms raised in exuberance. The impossible has happened. They’ve held on. He’s held on. Against all odds: Kasper Asgreen.

Some days you cover bike racing and expect a sure-fire answer. Today was one of those days. You fall asleep in the car on the long transfer to the press room. You try and find obscure facts about Philipsen because he’s won four times and everyone’s running out of things to say. You go into the day thinking, I’m gonna have to make the inevitable exciting, which is a very different task than writing about the unexpected. I did not think the break, first three riders and then four, would make it against a motivated peloton.

I’m not the only one either. Luka Mezgec, leadout-man extraordinaire for Dylan Groenewegen, stares wide-eyed in disbelief as he tells me, “I mean still, I dunno, how is this possible? To be honest, like more than 12, 13 riders were pulling all day. The last 20, 30 kilometers were like full-on and there were three, four guys just keeping on the distance. I mean, we burned four guys … Alpecin four. Trek pulled two guys. I guess Bora, two. DSM also is pulling all day, so I don’t know.” You can see him unpack the loss in real time as he tries to talk through it. For the Quick-Step boys, it’s a day of relief. Theirs is no longer a winless Tour. Yves Lampaert takes photos with fans. He says, “I think the guys in the front were just too strong. [The others] did everything perfect.” Perfection didn’t win out over perseverance.

But the biggest surprise is Asgreen, a man who has been nigh invisible since his win in the Tour of Flanders in 2021. In the presser, he admits to having had a difficult time. He dedicates the win to everyone who helped him return to form, slowly but surely. There’s a wide, broad smile on his face, which is saturated with happy relief. You can’t help but smile watching him talk, listening as he says, with total confidence: “I’m back where I belong.”

What did you think of this story?