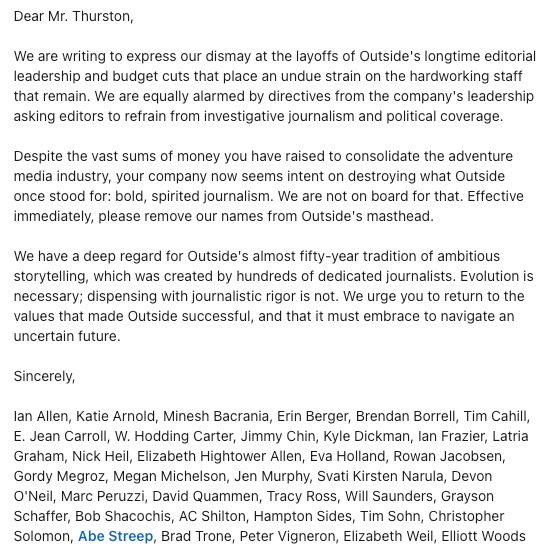

This week, 35 high-profile writers, editors, and photographers sent a letter to the CEO of Outside Inc., Robin Thurston, demanding that their names be removed from the masthead of the media conglomerate’s marquee and eponymous magazine, Outside. Signees included Academy Award-winning filmmaker and photographer Jimmy Chin; Tim Cahill, one of the magazine’s founders and a legendary adventure journalist; and renowned author Hampton Sides, among others. In many cases, they signed the letter at great professional cost.

“Your company now seems intent on destroying what Outside once stood for: bold, spirited journalism. We are not on board for that,” the letter states, before demanding that their names, which provide the credibility upon which the magazine trades, be removed. Outside appears to have responded; its current masthead no longer lists their names.

The letter comes after half a decade of consolidation of outdoor media titles by Thurston, first under Pocket Outdoor Media before that entity was rebranded as Outside, Inc. That consolidation has been accompanied by three rounds of layoffs affecting more than 150 people, plus the shuttering or withering of more than a dozen titles, including three within cycling — Peloton, a print title, Velo, which exists in digital form but had its print arm cut off, and CyclingTips, where I was the Editor-in-Chief until I was laid off in November 2022. Within weeks of that event, much of the staff quit. That title was shuttered a few months later.

Outside Magazine itself was somewhat sheltered from all this turmoil until this February. Roughly a month ago, around half its full-time staff were let go. The cuts primarily hit senior-level editors, including the brand director, managing editor and two senior editors. In the early chaos of the news, there were reports that just four editors remained at the title.

An Outside Inc. spokesperson told Adventure Journal that this early four-staff-left figure was incorrect. They claimed that more than 60 "full-time content creators and contributors" were still working on the editorial team, a line Thurston repeated in his email response to the initial masthead removal demand. But there's some rhetorical sleight-of-hand in that contention. While Outside Magazine's masthead formerly had a lengthy roster of contributing writers and photographers, they're all independent freelancers, not full-time staff. The magazine's full-time editorial staff has never been even close to 60; including digital editors, photo editors and designers, it numbered around 30 in 2020 and slightly higher than that even in the magazine's early 2000s heyday.

So the "over 60 full-time content creators and contributors" appears to count staff working for other titles within Outside Inc. In any case, the current full-time editor count on the updated masthead is nine. That means the full-time staff of one of the most storied publications in outdoor media is smaller than here at Escape Collective. I mention this not as a gotcha or to brag, but as an indicator of how the company is now set up to operate, funneling and syndicating content across brands like a content hydra, where every severed head spits out the same stories in a slightly different font.

The reality is the magazine has been gutted. Those left are capable professionals, but even if Outside still had a robust staff of journalists, Outside Inc. has demanded, according to the letter sent to Thurston, that reporters and editors “refrain from investigative journalism and political coverage.”

This kind of public backlash from high-profile contributors has been building for half a decade, as almost half of the brands acquired by Pocket/Outside ended up gone or a shell of their former selves since Thurston started pulling the company together.

Forest fires are a useful analogy here. They are swift, hot, devastating, and seemingly indiscriminate. They burn the strong and the weak, the big and small, and leave behind little of what once existed.

But fires also lead to rebirth. Some species of tree rely on fire to regenerate, through dormant, below-soil buds or serotinous cones that only open to spread seeds when exposed to extreme heat. Little shoots pop up, bright green against the black and brown and gray, wiggling their way upwards incessantly toward the light. Some will become next decade’s great trees; others will wither, despite their will. That’s where outdoor media is today. It feels like it's time, after quite a long wait, to discuss how we got here.

Kindling

Near the end of 2017, I handed in my notice at VeloNews. I’d signed somewhere else, swapped teams, and was headed to upstart CyclingTips as their new Senior Editor. I did this partly to escape the clutches of VeloNews' incompetent owner at the time, Competitor Group. Just weeks before I left, VeloNews was purchased by Pocket Outdoor Media, a small group led by former owner Felix Magowan and fellow investors Steve Maxwell and Greg Thomas. I recall Felix walking through the old offices in Boulder, sitting down with all of us. He did my exit interview, if you could call it that. Robin Thurston was not mentioned in the initial press release.

The shortest version of the story, because this part is boring, is this: Roughly two years later, Thurston, who sold MapMyFitness to UnderArmour for a reported $150 million, added significant investment into Pocket Outdoor Media. At the same time, he became CEO. Magowan and Maxwell stayed on as shareholders but relinquished most day-to-day control. And the seeds of Outside Inc. were planted.

The scale of Thurston’s ambitions were clear in the first press release after he became CEO. “We will become the global home for athletes,” he was quoted as saying.

Here’s how that played out.

In June 2020, less than a year after Thurston came on as CEO, a Series A investment round raised $16.5 million from Jazz Ventures, Lance Armstrong’s NEXT Ventures, and Zone 5 Ventures, the venture firm of Mike Sinyard and Specialized. Pocket acquired Active Interest Media, which included adventure filmmaker Warren Miller, Yoga Journal, SKI, Climbing, Backpacker, and Vegetarian Times, plus half a dozen other titles. In October, Pocket added Big Stone Publishing, which included Rock & Ice, Trail Runner, and Gym Climber. Rock & Ice was quickly folded into Climbing magazine. In November, Pocket acquired FinisherPix.

In February 2021 it was time to play with the big dogs. Sequoia Capital, the legendary Silicon Valley VC firm, led a Series B investment round of $150 million. Lance’s NEXT and Sinyard’s Zone 5 were part of the round as well. Pocket then acquired Outside Integrated Media, which included Outside Magazine and Outside TV, and rebranded the whole company Outside Inc. At nearly the same time, the group separately acquired Gaia GPS, a mapping company, athleteReg, and Peloton.

After five months came another set of acquisitions. This time it was Pinkbike, the mountain bike title, CyclingTips – a great website if I may say so – and Trailforks, another mapping service. In November of the same year, the rebranded Outside Inc. acquired Inkwell Media, a marketing agency, and Roam Media, an outdoor Masterclass-like education company.

In March 2022, Outside acquired Fastest Known Time, which does what it says on the tin. That brought the total acquisition count to around 30 titles and brands. Around the same time, the Federal Reserve began to raise interest rates and the era of easy VC money began to come to a close.

In May, 2022, the first major round of layoffs hit. It affected roughly 15% of staff, according to reports at the time, or roughly 80-90 people. Peloton Magazine was killed around this time, though its founders stayed on with the company until February of this year. Beta, a mountain bike magazine that is, to date, the only new title Outside Inc. has launched, was closed after just 16 months in existence, having produced just a handful of issues. Oxygen, a women’s magazine, had its print product killed and these days has stories on its homepage from years ago. Even surviving titles suffered. Trail Runner, Backpacker and Climbing all saw reductions in print frequency of 80% or more.

But acquisitions continued. In October 2022, Outside acquired Stomp Sessions, which, like Roam Media, became part of Outside Learn, its video education arm. In November 2022, in a second round of cuts, I was laid off along with another cull of roughly 12% of staff, again according to reports. That included my CyclingTips colleagues Matt de Neef and Dave Rome. Dane Cash had been let go in the first round of layoffs.

By February 2023, CyclingTips was effectively dead, since most of the staff had left. Backpacker went to a fully digital format, enraging my father-in-law. After more than 50 years in print, Velo went fully digital as well. My father-in-law was only slightly miffed by this one.

All was quiet for a while. Then, in February, the axe came for Outside Magazine, leaving half the former staff count to run the website and print product. At the same time, Outside Inc. announced it had acquired Inntopia, a travel booking platform, for an undisclosed sum.

Ecosystems

The forces behind media’s general decline, visible in Outside’s struggles over the last half decade, are familiar but newly intensified. Print advertising dried up with the rise of digital media. In its place, digital advertising became the dominant revenue model for media outlets, but three companies—Alphabet (mostly via Google and YouTube), Meta, and Amazon—have captured an estimated 67% of total global ad spending. That includes digital, print, video, and outdoor, and so those three companies capture an even higher share of digital ad revenue, leaving media companies scrambling for scraps.

Venture capital and private equity firms saw an opportunity, injecting money into legacy brands with promises of growth and transformation. But their strategies of rapid expansion, cost-cutting, and a relentless pursuit of scale often left the core product weakened. By that I mean the content sucked, which is what happens when you remove all the people making it. Instead of investing in journalism, companies prioritized algorithms, audience data, and “content strategies” designed to feed an increasingly fickle digital marketplace. They then wondered why audiences felt zero connection or affinity to their brands and moved on at the first opportunity.

The result was a familiar pattern of destruction. Sports Illustrated, once the gold standard of sports journalism, was passed from one corporate owner to the next, each round of cuts eroding its editorial strength until it became a shell of itself. Deadspin was acquired, mismanaged (including a fateful editorial choice that vastly accelerated its demise), and ultimately abandoned by its editorial staff in protest; many of them then started Defector. The Village Voice, Rolling Stone, Time, and countless alt-weeklies suffered similar fates, casualties of consolidation and corporate short-termism. At some point, nearly every storied magazine has faced the same choice: either be absorbed into a conglomerate or struggle independently against the economic tides. Few have survived intact.

This is what Thurston has pointed to as a mitigating factor in all the media brands he’s shut down. "Headwinds" is the preferred term. These titles were probably doomed anyway, is the rationale. Many were indeed bloated and barely hanging on. Yet many now-dead titles, like CyclingTips, were profitable prior to acquisition. Others were break-even, according to chats I've had with former staff.

Partially because of these structural problems, there’s a common belief in media: the best media businesses aren’t really media businesses at all. They’re just fronts for something else – an events company, a marketplace, a data aggregator. Content brings the traffic, the brand brings the credibility, but the real money is somewhere else. Sports Illustrated, for instance, is currently owned by a company called Authentic Brands Group, which licenses the right to publish the title, but is primarily focused on leveraging SI's legacy and brand for events, merchandise, and partnerships in industries like sports betting.

I am, let me tell you, intimately familiar with the difficulties of running a media business, and there’s some truth to this idea. At least if you want the sort of scale Outside Inc. has been chasing.

Robin Thurston didn’t see Outside as a media company. He said so, plainly, many times. Outside Inc. was a tech company of sorts, a data play maybe, but not a magazine publisher. As far back as 2021, Thurston spoke of his goal of taking the company public within three years. That’s how you get $150 million from Sequoia – venture capital doesn’t invest in journalism, it invests in scale. But there was a problem: the foundation of this empire wasn’t built on tech. It was built on media, particularly print magazines.

The earliest acquisitions – VeloNews, Climbing, Rock & Ice, Backpacker, Peloton – were all traditional media businesses. Small, niche, and built around loyal but limited audiences. They were never designed to be more than that, never meant to fuel a lofty IPO. So the strategy was to keep bundling, grabbing as many niche media brands as possible, stitching them together into a single subscription package, and hoping the sheer volume of content would attract enough paying customers. Add mapping, add event registration and travel booking. Gather the world’s outdoor enthusiasts and provide them with information (in the form of content) and a way to use that information to spend money.

Bundling is nothing new. Media companies bundle and unbundle constantly. Netflix is a bundle. Streaming unbundled the business model of cable TV. Now everything is rebundling again (call it "cable" again for nostalgia). The idea makes sense – if you're trying to get people to pay for content, it helps to have a lot of it. But media bundles only work when the content within them retains its value.

The unscaled media parts of Outside’s bundle never stood a chance. Thurston's publicly-stated goal back in 2021 was 20 million subscribers in five years. For context, The New York Times has 11.4 million subscribers after decades of growth, a newsroom staff in the thousands, and a digital presence that dominates global media, with valuable companion divisions like sports site The Athletic, OG reviews site Wirecutter, NYT Cooking, and its popular Games vertical.

Outside was starting with 1.2 million subscribers, most of them from mapping apps like Gaia GPS and Trailforks, not the magazines. To hit Thurston's goal numbers, the core of the business – the media brands – would have to transform from slow-growing, audience-driven outlets into high-growth machines. They had to be something they never were or could be.

When growth doesn’t materialize, investors get nervous. The market shifted. Interest rates rose. And suddenly, all those magazines, all those journalists, all those subscribers who had once been central to the plan, were now just dead weight.

The layoffs began. Titles were shut down. Print editions disappeared. Investigative journalism was discouraged. The entire company pivoted toward travel booking, digital products, and events, the real money-makers. And NFTs for some reason.

There are few blunter examples of leadership getting their heads turned by tech than Outside's short-lived foray into the world of crypto. At the height of the crypto craze, Outside jumped on the NFT and metaverse bandwagons. About five months before CyclingTips crumbled, Outside issued a press release titled “Jack Johnson joins the Outerverse,” a hilarious headline in the year 2022. The somewhat-past-his-prime but still internationally renowned singer duly revealed Outside’s first NFT, the Bedrock Badge, and played a sparsely-attended concert near Times Square. The cost? You don’t want to know.

Matt de Neef wrote a funny story about Peter Sagan’s NFTs for CyclingTips in August 2022. It was titled “If Peter Sagan can’t sell an NFT, then nobody in cycling can.” He carefully wrote around the efforts of our bosses to do exactly that but – and I want to make clear this is public knowledge – that story was then pulled without public explanation. The good news is there were a bunch of random blogs that used to scrape everything CT published and repost it, so you can still read it.

The Outerverse/Outside.io was "paused" roughly a year after launch and then permanently closed. It was Outside's highest-profile flop but not its only one. Among the flurry of early 2020s acquisitions was Cairn, which featured brand-name outdoor gear and became Outside's in-house e-commerce arm, Outside Shop. That initiative was also quietly shuttered as layoffs mounted. Current projects include an AI-powered chatbot, called Scout, and a digital redesign around a social media-style feed that is currently devoid of almost any social interaction.

This is what happens when one tries to graft a tech company growth model onto media. The incentives don’t align. The values don’t align. Good content isn’t about scale; it’s about depth, and deeply understanding an audience.

Little green media sprouts

That’s the spark that lit the fire that ripped through outdoor media. It burned down Peloton and CyclingTips and Rock & Ice. Velo is scorched and battered. It charred Climbing and Ski and left Backpacker as little more than a curled crisp of paper. It came, finally, for the big Outside Magazine old-growth sequoia right in the middle of the forest, standing tall for decades. All but a few branches are burned to the ground. And now they’ve angered Jimmy Chin and his 3.5 million Instagram followers.

Fine, that’s business. Media is hard and Outside has pivoted for survival, not out of some sort of menace. That doesn’t make it any less sad. I have largely avoided commenting on Outside’s various machinations since the end of 2022, first because there are still superbly talented people there doing their best to build things and second because sour grapes are gross. So I want to be clear that there are none.

The decision to remove me from my post at CyclingTips turned out to be great for me; we now control our own destiny here at Escape. I am very aware that I write this piece with the benefit of hindsight and, perhaps oddly, quite a lot of empathy for Robin Thurston and anybody trying to build media in this era. I’d have done lots of things differently but there’s absolutely no saying my version of Outside would have worked any better while Zuckerberg and Bezos still have their thumbs on the scale.

The end result is the end result, though. By our count, Pocket and then Outside Inc. acquired 44 distinct entities – editorial titles, divisions, and businesses – across more than a dozen deals. Sixteen have since been shut down. Another three were sold, and three more merged. Of the remaining active media titles, almost all have been heavily downsized, losing print products and dropping staff sizes. Dozens of people have had their professional lives turned upside down.

Hanlon’s Razor tells us not to ascribe to malice what incompetence can explain. But through all this, Outside’s alleged directive barring investigative journalism is deeply concerning. It takes a certain kind of business to support ambitious, fearless reporting that holds power to account, and Outside no longer appears to be that business. Can Substack do that? Digital media thrives on building habit through frequency, and it’s hard to see the economic incentive for a newsletter solopreneur to devote weeks to a single story, no matter how impactful. We see it as part of our role at Escape, but we’re just one entity.

For sanity’s sake, we have to choose to view the positives. The founders of Peloton just launched a new magazine called Fausto. The founder of Summit Journal is a former Climbing editor. Print magazines like Adventure Journal and Mountain Gazette, these big, heavy, expensive, beautiful things, prove that paper has a future. The former Editor-in-Chief of Velo, laid off the same day as I was, now has a successful Substack. These are all media titles asking you to pay directly for something you value, and largely succeeding at it.

This is why Outside’s failures don’t suggest the demand for quality journalism is dying. All these new green shoots prove market appetite.

We’re still here. Two years ago this week, Escape Collective launched out of nothing. There are 14 staff here now, almost all of whom were pulled from the ashes of Outside. We’re building a sustainable media business, slowly, one focused on providing value for our members above all. We do so without fear or favor. IPO isn’t the goal, good journalism is. (So please sign up?)

Unsurprisingly, a letter crafted by 35 of the best creatives on the planet has some great lines. “Evolution is necessary; dispensing with journalistic rigor is not,” they wrote to Thurston this week. Change is constant, media is hard, but the best way to guarantee failure is to forget what makes audiences show up in the first place.

Did we do a good job with this story?