The issue of rider safety is not new by any stretch, but it seems finally to be getting the attention it deserves – or close to – in a sport in which performance demands its participants put themselves in acutely risky positions on a daily basis, whether they're racing or training.

In the past few years, cycling’s governing body has been under significant pressure to improve safety measures. Horrific incidents like the Tour of Poland crash that almost cost Fabio Jakobsen his life in 2020, the season-defining pile-up at last year’s Itzulia Basque Country, and the deaths of Gino Mäder and Muriel Furrer in the past two seasons have all prompted vital reflection, but as crashes continue to happen, progress continues to feel slow.

However, now that the UCI’s SafeR project is fully functional 18 months after having been announced in 2023, there’s hope that things might start moving in the right direction, and indeed, since the first phase of testing began last summer, new regulations and specifications are coming into effect. That said, many ideas and updates have come hand in hand with a hefty measure of skepticism.

Last June we saw the introduction of a number of new measures such as yellow cards, extending the sprint safety zone, simplified time gaps and changes to race radios, with mixed success. And throughout the year, the project was also mining data on all crashes and near misses at UCI events. Earlier this week, with the Women’s WorldTour season about to get underway at the Tour Down Under, the UCI published an update on their research and the measures to promote safety in races.

Here’s what we learned about the project’s progress, and the gaps we found along the way.

First thing’s first, what is SafeR?

SafeR (as in ‘SafeRoadcycling’) is an initiative founded on improving safety in road racing that brings together a range of stakeholders within the sport: the UCI, race organisers, commissaires, teams and riders.

Those involved on the various boards – Supervisory, Commission, and Case Management – include directors of all three Grand Tours, course designers, WorldTeam general managers and staff, UCI representatives and former riders, all of whom come together a number of times a year, depending on committee level, to review everything from race incidents and safety audits to strategic and budgetary decisions.

One of SafeR’s first endeavours was to find a way to collate crash data, taking into consideration the seriousness of the crash and everything that might have contributed to an incident, whether that be weather, broken road surface, descents, equipment failure, rider error, etc.

The UCI race incident database

In 2021, the UCI entered into a collaboration with Ghent University’s Department of Information Technology to establish a race incident database that would support decision making within the sport, facilitating the creation of applications, measures and tools to analyse and act upon safety-related incidents.

According to the database’s simple landing page, the research group makes use of an “automated Twitter scraper” to populate the database with incidents within the UCI race calendar as a starting point – one of the objectives of SafeR is for measures to trickle down from the professional levels to lower tiers of road racing – and from there other stakeholders like the event’s commissaires can amend or add to the raw data and course analysis. The IDLab research group, led by Professor Steven Verstockt, can then analyse the findings and ultimately provide essential insights into current and future safety measures, and even advise where disciplinary action may be appropriate.

2024 findings

In 2024, a total of 497 race incidents were recorded on the UCI race incident database in the top two tiers of women’s and men’s pro cycling (WorldTour and Pro), and were sorted as follows:

- 35% – “unprovoked rider errors”

- 13% – “situations of tension” related to the course or race tactics, e.g. climbs, cobbles, sprints

- 11% – hazardous road conditions, specifically weather related

- 9% – road infrastructure, including road furniture and traffic-calming measures

- 4% – poor road conditions

- 1% – behaviour of other vehicles

And the other 27%? The report does not acknowledge the remaining portion at all, which amounts to 134-odd incidents, presumably due to difficulty categorising them either through non-specific causes and conditions, or a lack of data to begin with, but whatever the reason, it would be good to know …

Another glaring omission is any explanation of "unprovoked rider errors". Presumably things like sprint deviations would be included, and other negative bunch behaviour from lead-out and support riders, but what else qualifies for this most significant category of data?

This also raises the question of methodology. While the UCI’s update provides no details, the research group’s own write-ups routinely cite “course analysis and automated Twitter incident scraping.” Sliding over the out-of-date reference to a website that has not been called ‘Twitter’ for almost two years, it seems a curious thing on which to depend so heavily, at least without further explanation of the information gathered.

Then again, as a free and legal source of data, perhaps it’s the best and most efficient option, especially given it will then be sifted through by people in the know and Ghent University’s analysts. Nevertheless, hopefully future reporting will give us a better look at how the data is collected and treated once the database is accurately populated.

Measures already in motion

You may well remember that a few measures were tested in the latter half of the 2024 season, starting at the Tour de France, the results of which were paired with surveys taken from those in and around the racing.

- A yellow card system – during the testing at women’s and men’s WorldTour events, 31 yellow cards were issued over 66 days: 52% to riders; 32% to team staff; 16% to media vehicle drivers and pilots. The 21-long list of infractions warranting a yellow card are listed in article 2.12.007 of the UCI Regulations. For example, Barbara Guarischi earned the first ever for “improper conduct that endangers others in the final sprint” on stage 2 of the Tour de France Femmes; and no less than four (of seven in one day) were handed to Decathlon-AG2R for aggressive obstruction during stage 11 of the Vuelta a España – read Joe Lindsey's analysis of a big day for the yellow card initiative here.

- Adaptations to the use of earpieces – the testing included reducing the number of riders wearing earpieces to two per team, and blanket removal, with a survey also contributing to the results – the 349 completed responses included 240 riders and 42 team representatives from men’s cycling only.

- Changes to the ‘sprint zone’ – extension of the ‘three-kilometre rule’ to up to five kilometres, except summit finishes, subject to the approval of the UCI; also simplifying the calculation of time gaps on sprint stages from one to three seconds, except in the case of distinct breakaways, i.e. reducing the pressure on non-sprinters to stay in touch with the bunch. Part of the justification for ‘sprint zone’ alterations is to account for the increasing presence of traffic-calming measures in urban areas, all of which present a hazard to a speeding peloton.

While the use of earpieces is still a source of debate (more below), the test phases for the sprint zone and yellow cards led to approval for continued use in 2025, with modifications and/or improvements to both. Besides the need for better barriers and course design – for instance, late corners or downhill finishes – something that was particularly important to the 174 riders surveyed on the subject of sprint finishes was the need for consistency in handing out sanctions for both sprinters and their lead-out riders.

Not that any of these 'findings' are in any way groundbreaking; they're all features or approaches that the sport has long been aware of and that many have relentlessly advocated for – inconsistency re sprint deviations, for example – with little or no action.

In the case of yellow cards, the initiative will expand to include more events, and an extension of the list of infractions to include dangerous behaviour in the leadout and to team staff or assistants who attempt “to feed their riders in a dangerous manner.”

This season’s first yellow card has already been presented on stage 2 of the women’s Tour Down Under. Uno-X Mobility director Anna Badegruber was the guilty party having passed too close to the peloton on her way to assist team leader Mie Bjørndal Ottestad was caught up in a crash – the Norwegian climbed to third on stage 2 and ultimately finished third overall. Badegruber was also fined 200 CHF and the yellow card meant that the director had to be extra vigilant on Sunday’s final stage given that a second infraction in the same race would see her ejected and handed a seven-day suspension.

“If the commissaries decided it was too dangerous and I deserve a yellow card for that, then that's how it is, and we will move on from that. But obviously, you don’t want to get a second one in the same event, because then you’re out,” Badegruber told Cyclingnews before stage 3. “It will be super stressful. For sure, with moving in the cars or feeding or anything now you probably have it a little bit on your mind, ‘Am I doing everything right? Is it correct? Is it not? Which rules apply?”

While it’s stressful for the implicated party and their team, this particular case is neat proof of concept: the commissaires’ reasoning seemed pretty clear, the sanction timely and justified, and the warning appears to have had the desired effect on those involved.

But just how effective are these measures?

Escape Collective’s Ronan Mc Laughlin has argued that yellow cards and the amended five-kilometre rule are merely sticking plasters covering up but not fixing the deeper issues. Writing a few weeks after Muriel Furrer’s fatal crash at the World Championships in Zurich, Ronan suggested four simple (common-sense) fixes that the UCI could implement right now, without a lengthy process of data gathering, analysis and debate.

Among them was a sincere pushback against what Ronan sees as a curious desire to ban race radios, and evidently many agree with him. Indeed, SafeR and the UCI are shifting their focus away from the question of whether to ban some or all rider radios, and instead homing in on how they’re used to communicate information.

New measures under review in 2025

In addition to the above tested safety measures, SafeR has recommended changes in other areas from the start of this season.

Fixed feed zones – in order to increase both safety and equality among participating teams, race organisers are required to position fixed feed zones every 30-40 kilometres in conjunction with litter zones, taking back the allowance for feeding anywhere along the route that was introduced during the pandemic.

Barriers at the finish – the second phase of barrier testing will “define the specifications and approval methods for the barriers to be used in the last 500 metres of races.” Through the remaining six months of this study, SafeR and the UCI are aiming to produce new standardised specifications, including the barriers’ dimensions, mechanical functions and fixing methods, as well as stipulations re the positioning and attachment of advertising. These will presumably build on the continuous solid barriers that entered regulations the winter after Jakobsen’s Poland crash.

Also under review are other course-related safety measures and tools that may include additional features like cushioning along particularly hazardous stretches of road or fixed to road furniture, flags and signage that guide the riders, and software to help evaluate the possible risks along a race’s parcours.

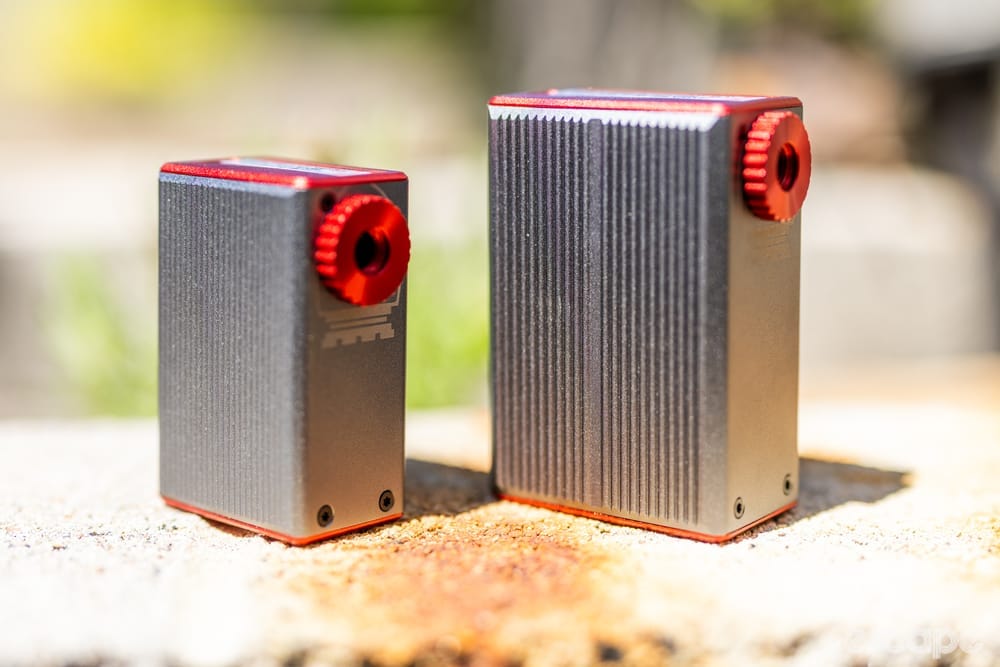

Ensuring safe distances between riders and vehicles – with high numbers of in-race vehicles, including TV motos and even VIPs, SafeR is exploring the feasibility of a device that would measure the distance between riders and the vehicles around them.

Equipment-related solutions – one of the more long-term projects includes addressing rider-centric issues like rim height and handlebar width, airbags, and the subject of gear restrictions (chainring sizes).

The equipment-related proposals have drawn mixed responses from riders, teams and industry insiders, as reported by Escape Collective’s Ronan Mc Laughlin, with the latter in particular finding itself under the spotlight in the past few weeks thanks to statements from the likes of Chris Froome and Wout van Aert. While rim depth is perhaps the least contentious and cockpit setups are dividing the crowd, many are dubious as to whether gear restrictions in particular would do anything to materially improve rider safety. In fact, it may be more dangerous.

In conclusion, it’s only fair to acknowledge that the UCI and SafeR are making steps forward. Whether they’re on the path or in the lane that the wider cycling world would like or that would get the best, or fastest, results is harder to say, but the very formal structure of the project is attempting justifying the measures they’re pursuing, and in the case of sprint safety zones and consistency of sanctions, they’re also backed up by common sense.

And yet, questions remain. Research methodology, for one, including the way incidents are categorised (my kingdom for an example). And what of the vast and increasing number of vehicles in the convoy, some – if not many – of them very much not crucial to the running of the event. And why is route evaluation being made so complicated? We’re all for showing your working, but not at the detriment of progress.

Did we do a good job with this story?