The Monuments of cycling are so named because of their heritage and the prestige that comes from winning them. This year's men's Tour of Flanders was no exception, with animated racing keeping proceedings open until the last 18 km, when Tadej Pogačar took the race by the scruff of the neck, heading off in pursuit of his second solo victory in Oudenaarde.

For once, the standard strategy of getting in an early move to be ahead of the race when the fireworks were ignited looked wise. By the time the attacks started flying, and the favourites began picking their way through those up the road, a lack of cohesion meant that riders were left out in front and in contention far later in the race than most would have predicted.

Any punchy one-day race provides rider data that is incomprehensible for your average rider, but Flanders often delivers stats that put the race in its own class. This year was no different, and the data uploaded by riders shows just how hard this edition was.

The numbers tell a story. Let's break down the race, section by section.

A 45 km battle to get into the breakaway

Before many of us tuned in to the coverage, the fight to get into the breakaway was on. The early break is often a place that second- or third-tier favourites aim to get into – the steadier effort and calmer run into the cobbled climbs can mean the break is an easier place to spend the first few hours of the race. Teams often send a rider up to be used later, usually called a satellite.

Anyone who finds themselves in the break will be hoping to pull out a big enough advantage over the peloton that they can last deep into the race before the inevitable capture takes place. Then all that is left to do is the small task of trying to follow two generational talents as they take sledgehammers to each other.

All of this is great on paper, but actually getting into the break can be just as hard as trying to hold on to Mathieu van der Poel's wheel, with attacks and counter-attacks flying before finally snapping the elastic, allowing a group to head up the road.

This year, one such rider who managed to find himself in the breakaway was Ineos Grenadiers’ Connor Swift. After 45 km, the eight-man break was decided, but the cost to get in this position, considering there were still 230 km of racing on the cards, was huge.

It was anything but a steady ride for Swift. For the race's first hour, his power spiked over 1,000 watts on 13 separate occasions. This repetitive abuse resulted from continually pushing at the front to either close down moves he wasn’t in or attempting to jump into moves that would hopefully be successful.

Once the breakaway had established itself, the contrast between fighting to get there and actually being there was stark.

The second hour was a steadier, measured effort for Swift, along with his seven comrades; getting their heads down, rolling through in an attempt to squeeze out every second of advantage possible before reaching the hellingen (the climbs).

Looking at the difference between the first and second hours of the race shows how advantageous getting ahead can be. Although the raw power isn’t all that different (only 12 watts between the two hours), the real story is the difference between the normalised values. 322 vs 371 watts is significant, and this steadier way of riding is far less taxing on the body.

The first hour of racing told a different tale for those looking to hide themselves from the onslaught at the front. One rider who was happy to give the battle for the break a wide berth was Gianni Vermeersch. Over the opening hour, his data could be mistaken for being taken from a different race than Swift's.

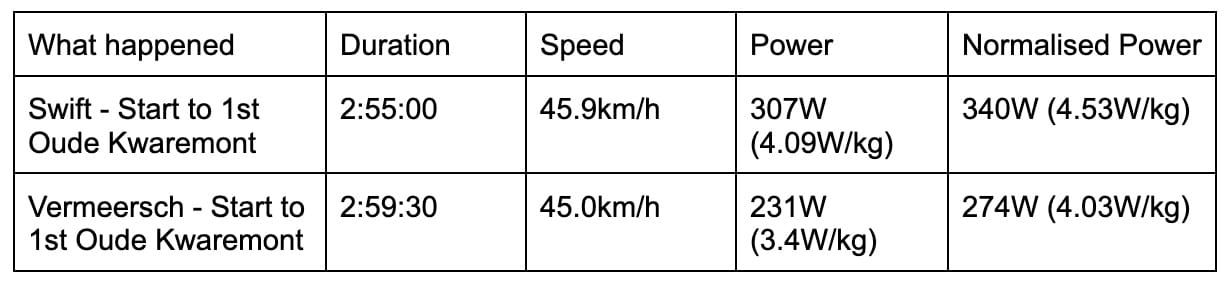

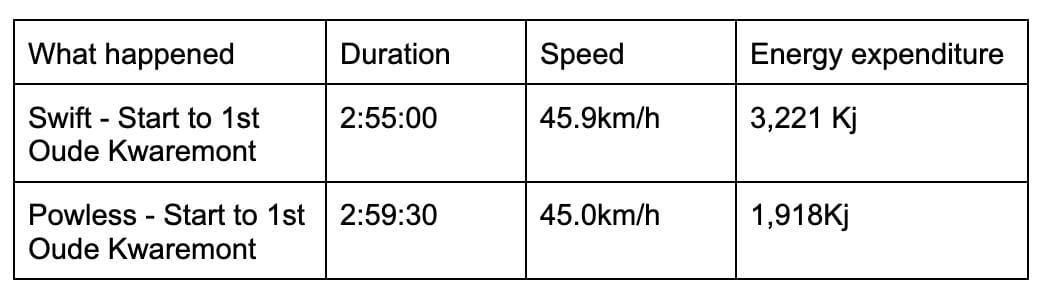

Before the race kicked off on the usual bergs of Flanders, around 134 flat kilometres had to be dealt with in total. For Swift and his breakaway companions, this took just under three hours, arriving at the foot of the Oude Kwaremont two hours and 55 minutes after leaving Bruges. Considering this is often seen as the start of the race proper, the break had expended significant energy to get there.

By the time the punchy climbs of Flanders rolled into sight, Swift had already accumulated a TSS of 179, equivalent to riding at almost one hour and 50 minutes at threshold. With what was in store, this hammers home that although getting ahead might be the smart thing tactically, and physiologically it can come at a significant cost.

This was not the case for Dwars door Vlaanderen winner Neilson Powless. By avoiding the wind and staying sheltered, he arrived at the foot of the Oude Kwaremont with a TSS of 97, nearly half that of Swift.

When we talk about energy loads in races, this difference cannot be overstated. When you take into account that the most energy-intensive moments of the race will come in the last 90 minutes, spending a lot of energy in the first half of the race will likely leave you with little in the tank when the crucial moment arrives.

The race arrives at the Oude Kwaremont

With around 140 km remaining, the race arrived at the start of the hellingen. Greeting the riders upon their arrival was the first of three ascents of the Oude Kwaremont. Averaging 4.8% for 2.2 km and with a maximum gradient of 11%, the Oude Kwaremont is one of the longest cobbled climbs in the race.

For Swift, the run into the climb was simple. With only seven other riders around him, there was no jostling for position, and instead, the septet rolled onto its slopes without any kerfuffle. In the 3.5 km before the climb, Swift averaged 307 watts with a peak of 995 watts.

Did we do a good job with this story?