Much of the talk after the first rest day of the 2023 Giro d’Italia was how the race would change with the sudden, COVID-19-forced departure of race leader Remco Evenepoel (and, increasingly, other riders). Did Primož Roglič intentionally arrive slightly under-cooked to peak in the pivotal third week? Will Ineos’s multiple-leader strategy work? And so on.

All of these storylines are important, but there’s one we’re not talking about much that’s just as big: thanks to weather, those pivotal high mountain stages might not look like you think they’re gonna look. And that’s something organizers should pay attention to for future editions.

For weeks now, there have been warnings that heavy late-season snowfall might prevent road crews from clearing the 2,469-meter Col du Grand Saint-Bernard, the race’s high point, in time for Stage 13 on Friday. And, sure enough, the race announced that it will instead detour through a tunnel instead of going over the pass.

Said tunnel is at almost 1,900 meters elevation, so there’s still some sting to it. But that’s not the only vulnerable point on the course. The original race route also passes over the 2,167-meter Croix de Coeur, also known as the pass above the ski resort of Verbier.

There are two issues race organizers have to deal with when assessing high-mountain passes: is the road plowed, and what is the weather forecast? It’s the first problem that nixed the Grand Saint-Bernard, but even though the Croix de Coeur is currently cleared, the late-week forecast isn’t promising. There's a strong chance of precipitation Thursday and Friday, including overnight, meaning it could fall as snow or freezing rain and bring the sport’s extreme weather protocol into play.

But wait, there’s more: Stage 19 is also in question, with three passes over 2,000 meters: the Valparola (2,195m), Passo di Giau (2,227m) and the finish at the Rifugio Auronzo hut at Tre Cime di Lavaredo (2,307m). The stage 20 time trial finishing on Monte Lussari is a little lower elevation, but was hit by snowstorms just yesterday.

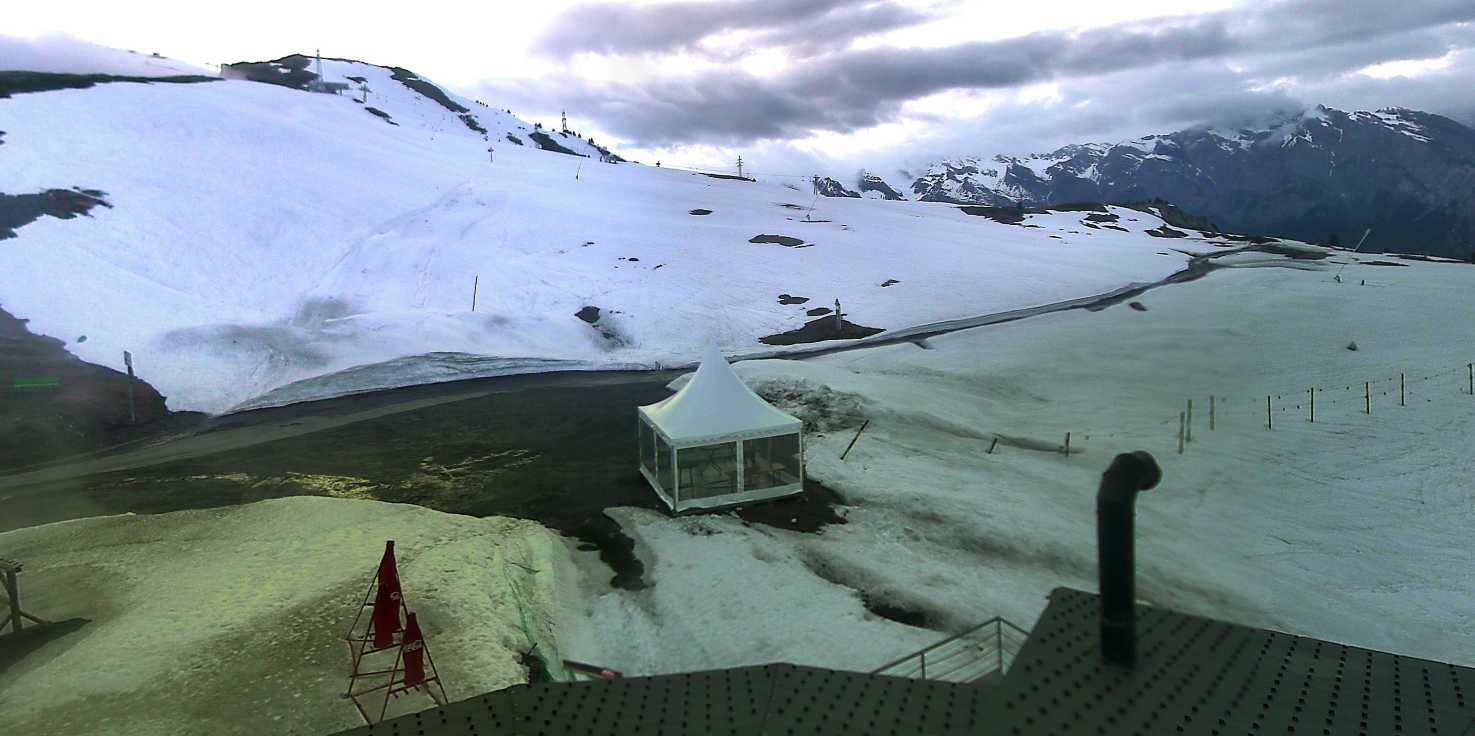

Just three days ago, parts of the Dolomites got a meter of snow, although webcams at the Passo Giau currently look clear. But this week’s forecast for the Rifugio calls for steady chances of precipitation with highs just above freezing most days. The first sunny weather isn’t until Monday, May 22.

As it happens, the last time the Giro – or any UCI race – visited Tre Cime di Lavaredo, in 2013, weather also forced course changes, including nixing the Giau. Somehow, organizers managed to preserve the full-height Lavaredo finish, and Vincenzo Nibali, who had led the race since stage 8, soloed to victory by 17 seconds over Fabio Duarte. But that was before the introduction of an extreme weather protocol.

Planning stages for the high Dolomites and Alps, months in advance, is a crap shoot. Earlier this winter, many European ski resorts closed for lack of snow. Now, too much of it imperils bike racing.

To address the hot-button question: is this climate change? It could be a factor. A warmer atmosphere carries more moisture, and thus more storm energy, which makes late-season dumps more possible at high altitude. When combined with the (thankfully) growing attention to rider safety, that’s something that organizers need to take into account when designing routes. Scenes like riders racing through fat wet flakes on the Lavaredo in 2013 – or the 1988 edition’s fabled Gavia stage where Andy Hampsten took the race lead in a driving snowstorm – might make for gripping drama, but that comes at the expense of riders’ health and safety.

There’s always going to be a place for the big, showy high-mountain test pieces, and if the weather allows it, the helicopter footage alone will make the Lavaredo finish worthwhile. But even if the climbs do get chopped some, that doesn’t necessarily dull the race. In recent Giros, the eye-candy stages with the longest, steepest climbs sometimes turn out to be defensive slogs where a few seconds get taken in the final kilometer or so, while more consequential racing happens on punchier, Classics-style courses.

Last year, stage 14’s lumpy, medium-mountain profile made for some of the most exciting racing in the Giro. In 2021, it was the Strade Bianche-style stage to Montalcino that was among the most memorable. And of course this year, Stage 8 saw not only Ben Healy’s long-distance winning move, but a spicy attack from Primož Roglič that put Evenepoel in difficulty.

As the sport – especially modern training – has evolved, riders are perhaps less vulnerable on long climbs than they once were. They are intensely in tune with their bodies, and have real-time data to lean on in crucial moments. They know what kind of effort they can sustain, and many smartly don’t go past it, hoping to recover and fight again another pass, another day.

All of that suggests that maybe the sport is changing too, and courses should change with it. For exciting racing, maybe organizers would be better suited to rely a little more on a different kind of unpredictability: that which comes from the race, not the weather. Trust the riders to make the race.

Did we do a good job with this story?