It felt like the dust had barely settled on the Oude Kwaremont before all the attention in racing refocused on Paris-Roubaix. The Queen of the Classics received even more hype than usual after defending Tour de France champion Tadej Pogačar announced his debut at the race.

Such is Pogačar’s talent that at a race he had never done before, on terrain that arguably didn’t suit his strength, he still entered as one of the top favourites. For others with hopes of a good result, getting into the early breakaway is a proven strategy to improve their chances of making it to the finish within touching distance of the front runners.

Unlike Flanders, Roubaix lacks punchy terrain. The cobbled sectors sting, but don't have the elevation component that Flandrian climbs like the Koppenberg or Oude Kwaremont do. This means that if you can hold the wheel, there is a far greater advantage to be had on the cobbles of Roubaix.

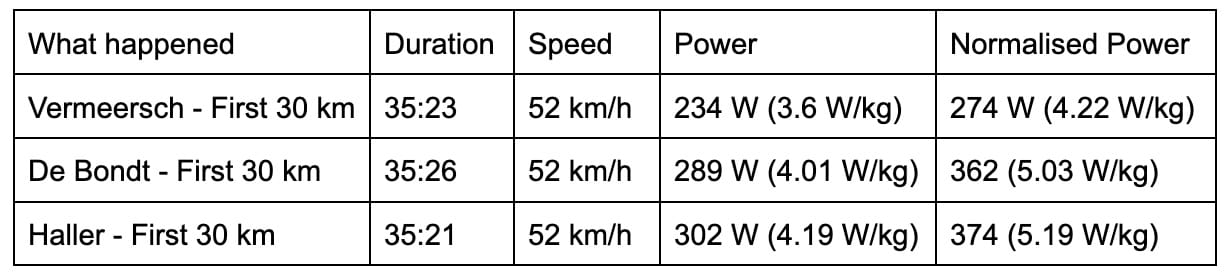

Gianni Vermeersch (Alpecin-Deceuninck), Dries De Bondt (Decathlon-AG2R La Mondiale), and Marco Haller (Tudor) all shared their power files on Strava. Taking a look at these sheds some light on what it is like to spend a day in hell.

Setting the early break wasn’t as tough as expected

In recent years, the duration and intensity of the battle that plays out to get in the break at Roubaix has dragged on until the race is at least halfway to breaching the first cobbled sector at Troisvilles – which typically doesn't come until almost 100 km into the race.

If the break can build up enough of an advantage to survive past the crucial Arenberg Forest sector at roughly 100 km to go, then there is a real opportunity for riders to cling to the coattails of what remains of a leading peloton and also avoid the carnage that descends on the cobbles as said peloton arrives.

As a result, every team without a favourite for the race wants to have a rider in the break before it heads off into the distance, while contenders' teams sometimes like to seed the break with support riders. In recent editions, racing through this phase has been incredibly aggressive, energy-sapping and stressful. In comparison, this year saw the peloton grapple with the formation of the breakaway for just over half an hour, or around a third of the length it had taken in previous editions.

For the eight-strong breakaway, getting away with only 30 kilometres of racing under their belt was promising. Given that the first cobbled sector was just under 70 kilometres away, and the infamous Arenberg lay more than 130 kilometres further on, this gave the break the best part of three hours to build and subsequently hold an advantage.

Vermeersch and De Bondt’s power numbers suggest the break formed with relatively little contest from the peloton. Although the average speed was 52 km/h inside the bunch, the intensity wasn’t off the charts.

Even though the break formation period only lasted 35 minutes, this saw numerous attacks and counterattacks fire off the front in a bid to be given some leash. This repetitive attack and catch motion saw a substantial delta between raw and normalised power, around 25% for De Bondt and Haller. Vermeersch did a better job during this phase at keeping his high-intensity surges to a minimum, managing to shrink his delta between raw and normalised power to 17% in comparison. But De Bondt's numbers are likely affected by his own attempt to bridge to the attackers, which lasted roughly 4 km before his small chase group was caught by the peloton.

Just because the break formed didn’t mean the chase stopped

In most races, once the day's break has been decided, the peloton takes the opportunity to knock things back a gear or two, take a nature break and get on with the task of balancing the lead of the break and conserving energy. At this year’s Roubaix, the eight-man group dangled off the front of the peloton for kilometre after kilometre, painfully dragging out a few seconds' advantage here and there.

It was only after 20 kilometres of this playing out that the break finally established itself and its lead ballooned to over two minutes for the first time. Although we unfortunately don’t have any power data from any of the breakaway riders, the body language and the visible effort etched on the faces of the riders show every second of advantage was hard-earned.

Did we do a good job with this story?